Month: August 2016

*Remaking the American Patient*

The author is Nancy Tomes and the subtitle is How Madison Avenue and Modern Medicine Turned Patients into Consumers. Here is one excerpt:

While unwilling to pass any kind of national insurance program, the U.S. Congress strove to advance the cause of “medical democracy” by other means. Instead of guaranteeing a right to medical care, legislators voted to spend public funds on hospital construction and basic medical research as a means to yield more and better treatment. To make that treatment affordable, the federal government looked to the private sector for help, using tax policy to encourage the growth of employee insurance plans. In this fashion, postwar political and business leaders hoped to create a free enterprise alternative to “socialized” medicine.

The first step toward expansion came in 1946 when Congress passed the Hill-Burton Act, which funneled federal funds into hospital construction and expansion. Over the next two decades, Hill-Burton funds would be used on almost 5,000 projects, many of them in rural areas that previously had had no hospitals. The program proved very popular, giving local communities a new institution to be proud of while creating more “doctors’ workshops” for medical education and private practice. At the same time, Congress vastly increased funding for medical research, from about $4 million in 1947 to $100 million by 1957. Postwar political leaders found appealing the idea of tackling cancer, mental illness, and other dread diseases through “a medical research program equal to the Manhattan Project,” as the National Health Education Research Committee urged in 1958. Taxpayer dollars helped to build up the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland, as the hub of what a later generation would christen the “medical-industrial complex”: a network of researchers located in American universities and scientific institutes whose careers depended on the generation of medical innovations.

I found this book extremely useful for understanding the evolution of American health care policy and institutions before 1965.

Faroe Islands fact of the day

Actuality, the Faroe Islands have a crude birth rate higher than that of Denmark, Sweden, or Norway. Their fertility rate of 2.37 is higher than anywhere else in the White world:

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2127rank.html

That is from Jason Bayz.

Thursday assorted links

1. The Great Olympics stagnation.

2. Danish family is more important than Danish environment in predicting earnings (pdf). And Danish children’s television is stranger than you think.

3. Mark Koyama on why the Roman empire declined.

4. Interview with John Cochrane.

The growing culture that is Swiss

While only 25% of the Swiss population hiked regularly in 2000, today the figure is 44%.

That is from Dina Pomeranz, original source here.

What you can learn from the Faroe Islands

Should you go? I give the place high marks for food and scenery, but the total population of about 48,700 limits other benefits. It is like visiting a smaller, more unspoilt Iceland. There is a shop in the main city selling Faroese music and many shops selling sweaters. They will not tell you where the sweaters were knitted.

The natives seem to think Denmark is an excessively competitive, violent, harsh and hurried place. The norm here is to leave your door unlocked. It is a “self-governing archipelago,” but part of the Kingdom of Denmark. In other words, they get a lot of subsidies.

But they are not part of the EU, so they still sell a lot of salmon — their number one export — to Russia.

You see plenty of pregnant women walking around, and (finally) population is growing, the country has begun to attract notice, and the real estate market is beginning to heat up. But prices remain pretty low, and it would be a great place to buy an additional home, if you do that sort of thing.

In the early 1990s, their central bank did go bankrupt and had to be bailed out by Denmark. It is a currency board arrangement, and insofar as the eurozone moves in that direction, as it seems to be doing by placing Target2 liabilities on the national central banks, a eurozone central bank could become insolvent too, despite all ECB protestations to the contrary.

Every mode of transport is subsidized in the Faroes, including helicopter rides across the islands. Often the bus is free, and there is an extensive network of ferries. I wonder how many population centers there would be otherwise. There is now the notion that all of the communities on the various islands are one single, large “networked city.”

The Faroes are a “food desert” of sorts, with few decent or affordable fruits or vegetables. And not many supermarkets of any kind. Yet the rate of obesity does not seem to be high. And they have a very high rate of literacy with little in the way of bookstores or public libraries.

The seabirds including puffins are a main attraction, but I enjoyed seeing the mammals too, with pride of place going to the pony:

The domestic animals of the Faroe Islands are a result of 1,200 years of isolated breeding. As a result, many of the islands’ domestic animals are found nowhere else in the world. Faroese domestic breed include Faroe pony, Faroe cow, Faroese sheep, Faroese Goose and Faroese duck.

The country receives a great deal of negative publicity for killing whales, but overall they seem to treat animals better than the United States does. Fish consumption is very high and there are no factory farms.

If the Faroes had open borders, but no subsidies for migrants, how many people would settle there?

In 1946 they did their own version of Faerexit, from Denmark of course:

The result of the vote was a narrow majority in favour of secession, but the coalition in parliament could not reach agreement on how this outcome should be interpreted and implemented; and because of these irresoluble differences, the coalition fell apart. A parliamentary election was held a few months later, in which the political parties that favoured staying in the Danish kingdom increased their share of the vote and formed a coalition.

Overall I expect this place to change radically in the next twenty years. It is hard to protect 48,700 people forever. In part, they are killing those whales to keep you away.

Is KOKS the best restaurant in the world?

I am told KOKS is a Faroese word for “adding something excellent,” though there are varying accounts of the translation. In any case, in terms of originality, purity of concept and vision, execution, service, and also view — taken as an integrated whole — I can’t think of any restaurant experience that comes close to this one. Noma in Copenhagen is a pale memory in contrast, as are the Michelin three-stars in San Sebastian. KOKS is still unspoilt and on the way up, and the guiding star is the very young and extremely personable Poul Andrias Ziska.

It has been written up in the New York Times and Guardian for its innovative take on Faroese cuisine, though both articles are now out of date. The dining room seats only 20, and Ziska is also the pastry chef, with no loss of quality. You’ll find photos and food descriptions on their Facebook page. Here is the shaved horsemussel on dried cod skin:

Here is one recent review:

Its cuisine style is earthy and refined, ancient and modern. Instead of the new, it emphasizes the old (drying, fermenting, pickling, curing and smoking) with a larger goal of returning balance to earth itself. At KOKS, the cuisine is about seasonality, seriously engaging with agriculture and history and of making age-old food delightful to modern palates…

Poul continues to simply enjoy the uniqueness and richness of the Faroe Islands. Fan of ræst, (local preservation method) he supports and defends this technique that captures and boosts flavour.

I can agree with this assessment:

And finally (and I have to say the best dessert I’ve ever had), dulse seaweed served with chocolate crumble, fermented blueberries and dulse mousse. Sweet, a bit tangy, a bit crunchy, silky-smooth on the mouth and simple heavenly. My marathon reward ended on a very special note.

I am willing to go out on a limb here: it is probably the best restaurant in the world right now. It alone justifies a trip to the Faroe Islands.

Addendum: Ethika, also in the Faroes, has some of the best sashimi I’ve eaten, recommended as well.

Nice

Accordingly, raising residential building requirements in high-amenity areas should cause those areas to move gradually to the left.

That is from Jason Sorens at Dartmouth, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Wednesday assorted links

1. “…the slowdown in TFP during and after the great recession is due to the decline in the speed of adoption of new technologies in response to the credit disruptions that shocked the US economy since the end of 2007 and that have affected the cost and availability of funds for companies until the end of 2013.” Short paper here (pdf).

2. This piece takes too long to get going, it is nonetheless an interesting take on how tourism is transforming Iceland.

3. Aetna’s retreat from Obamacare.

4. A mathematical history of taffy pullers.

5. Myths about Sunnis and Shias. Good piece, useful corrective.

In which ways is today’s world like the Reformation?

I can think of a few reasons:

1. Many of the structures in places are perceived as failing, even though in absolute terms they are not obviously doing worse than previous times.

2. There is a rise in nationalist sentiment and a semi-cosmopolitan ethic is starting to lose influence.

3. The chance of violent conflict is rising.

4. Dialogue is becoming more polarized and bigoted, and at some margins stupider.

5. Tales of gruesome torture are being spread by new publishing and communications media.

6. The world may nonetheless end up much better off, but the ride to get there will be rocky iindeed.

I have been reading Carlos M.N. Eire, Reformations: The Early Modern World, 1450-1650. Yes I know it is 893 pp., but it is actually one of the most readable books I have had in my hands all year.

Why do Danish-Americans do better than Danes?

That is one question I consider in my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

Nima Sanandaji, a Swedish policy analyst and president of European Centre for Entrepreneurship and Policy Reform, has recently published a book called “Debunking Utopia: Exposing the Myth of Nordic Socialism.” And while the title may be overstated, his best facts and figures are persuasive.

For instance, Danish-Americans have a measured living standard about 55 percent higher than the Danes in Denmark. Swedish-Americans have a living standard 53 percent higher than the Swedes, and Finnish-Americans have a living standard 59 percent higher than those back in Finland. Only for Norway is the gap a small one, because of the extreme oil wealth of Norway, but even there the living standard of American Norwegians measures as 3 percent higher than in Norway. And that comparison is based on numbers from 2013, when the price of oil was higher, so probably that gap has widened.

Of the Nordic groups, Danish-Americans have the highest per capita income, clocking in at $70,925. That compares to an U.S. per capita income of $52,592, again the numbers being from 2013. Sanandaji also notes that Nordic-Americans have lower poverty rates and about half the unemployment rate of their relatives across the Atlantic.

It is difficult, after seeing those figures, to conclude that the U.S. ought to be copying the policies of the Nordic nations wholesale.

There is more to the piece, and I will note that I see a Land of Twitter where many Danes have read only that part of the piece. I close with this:

How’s this for a simple rule: Open borders for the residents of any democratic country with more generous transfer payments than Uncle Sam’s.

Do read the whole thing. You can buy the Sanandaji book here.

Helen DeWitt’s *Lightning Rods*

Do you ever read someone and find you are too addled to tell when the author is being funny or not, and then perhaps some of you have the temerity to suggest your confusion is the fault of the author?

Well, imagine a whole novel like that, and about the hot-button topics of sex and above all power and power in the workplace and yes race too. Helen DeWitt can in fact get away with writing sentences such as:

One man said he was not exactly disputing the points made but he did not think he could reward his top earners with titless sex.

So yes, buy this book but do not read it, for the temerity will rise in your soul.

Helen DeWitt is a national treasure, yet collectively we have driven her to Berlin. We do not deserve whatever she plans on serving up next.

Here is my previous post on Helen DeWitt.

Tuesday assorted links

1. New Dobbie-Fryer results on charter schools and their impact.

2. The positive economic impact of universities.

3. “The last time I used the word vulgar was to describe an amaryllis.” (NYT) Good piece, good format, good spousal pairing. “The vulgar,” Phillips says, “refuse to miss out.”

4. Good questions about the inequality rise as coming across different firms.

5. “Electricity is like blood.”

6. Taleb on whether there is a payoff to asymmetric rules in favor of intolerance.

Regulation and Distrust–The Ominous Update

Here’s a post I wrote in 2009 (no indent) that I will update today:

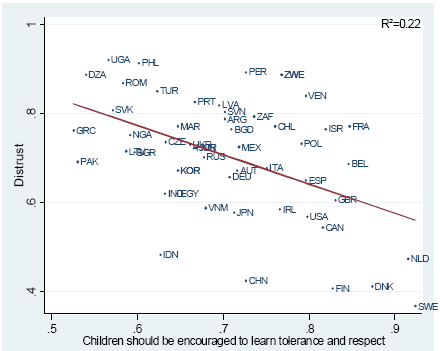

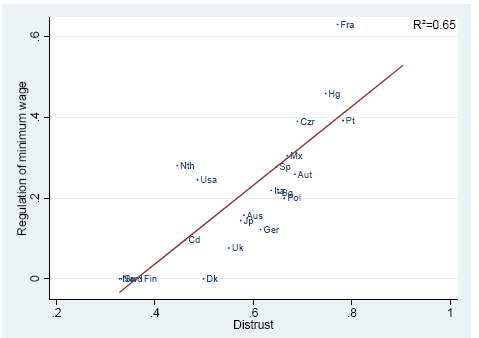

In an interesting paper, Aghion, Algan, Cahuc and Shleifer show that regulation is greater in societies where people do not trust one another. The graph below, for example, shows that societies with a greater level of distrust have stronger minimum wage laws. Note that the result is not that distrust in markets is associated with stronger minimum wages but that distrust in general is associated with greater regulation of all kinds. Distrust in government, for example, is positively correlated with regulation of business. Or to put it the other way, trust in government (as well as other institutions) is associated with less regulation.

Aghion et al. argue that the causality flows both ways on the regulation-distrust nexus. Distrust makes people turn to government but in a society with a lot of distrust government is often corrupt and this makes people distrust even more. Crucially, when people distrust others they invest not in the highest return projects but in human and physical capital that is complementary to distrust–for example, they invest in human capital that helps them bond with their group/tribe/family rather than in human capital that helps them to bond with “outsiders” and they invest in physical capital that is more difficult to expropriate rather than in easier to expropriate capital, even though in both cases the latter investments may be the all-else-equal higher return investments. Such distrust traps are quite similar to Bryan Caplan’s idea traps.

Aghion et al. argue that the causality flows both ways on the regulation-distrust nexus. Distrust makes people turn to government but in a society with a lot of distrust government is often corrupt and this makes people distrust even more. Crucially, when people distrust others they invest not in the highest return projects but in human and physical capital that is complementary to distrust–for example, they invest in human capital that helps them bond with their group/tribe/family rather than in human capital that helps them to bond with “outsiders” and they invest in physical capital that is more difficult to expropriate rather than in easier to expropriate capital, even though in both cases the latter investments may be the all-else-equal higher return investments. Such distrust traps are quite similar to Bryan Caplan’s idea traps.

Thus, societies with a lot of distrust generate regulation and corruption and citizens who don’t have the skills or preferences to break out of the distrust equilibrium. Consider, for example, that in societies with a lot of distrust parents are less likely to consider it important to teach their children about tolerance and respect for others.

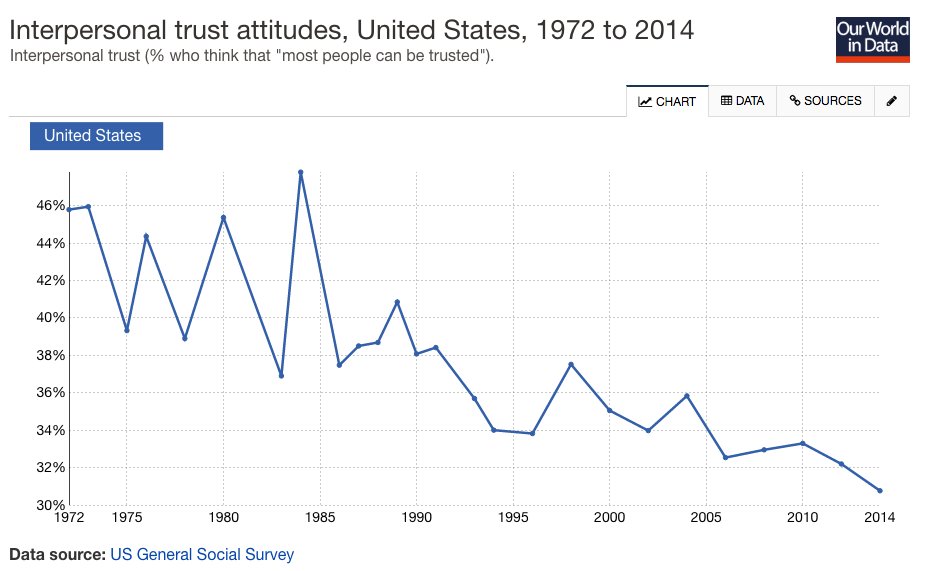

The update should be obvious. More and more this appears to be describing the United States. More distrust in government, more regulation, lower growth and more people who are so distrustful of one another that they can’t cooperate to break out of the bad equilibrium. Here drawn from Our World in Data is interpersonal trust in the United States.

Faroe Islands fact of the day

…the first monolingual Faroese-Faroese dictionary was only published in 1998, the first Bible in Faroese didn’t appear until 1961, and the language only won official status in the islands in 1948 with the introduction of the Home Rule Act.

That is from James Proctor, Faroe Islands. Here is some Faroese on YouTube. Here is a short (2:32) Faorese drama, with profanity in Faroese, subtitles too.

What if there are no more economic miracles?

Here is my Bloomberg column on the passing of the economic miracle, here is one excerpt:

Most of the world’s wealthiest and best-governed countries got there without super-rapid bursts of growth. Denmark, which has a per capita income of about $52,000 and is frequently ranked as one of the happiest countries in the world, never experienced what anyone would call an economic miracle. If you Google that phrase, the main entry will be a research piece detailing how, in the 1990s, the country lowered its unemployment rate without having to dismantle its welfare state.

Denmark’s overall economic record is gloriously boring. From 1890 to 1916, per capita growth averaged about 1.9 percent per year, and if in 1916 you had forecast that this pace would continue for another 100 years, you would have been off by only about $200. Denmark had positive growth about 84 percent of the time and no deep recessions, according to a recent study by Lant Pritchett and Lawrence Summers.

And this:

…the experience of Denmark and other “no drama” growth stories provides some clues to the future of developing economies. The East Asian growth model, for all its wonders, belongs to history. Slow and steady may be the only option left. For whatever reasons, few countries have been able to scale up their educational successes as rapidly as the East Asian tigers. Trade growth, which exceeded overall output growth in the late 20th century, now seems stagnant. Many export industries are automated and hence don’t create as many middle-class jobs as they used to.

In other words, today’s world may resemble the 19th century more than the last few decades.

Do read the whole thing.