Why Do Domestic Prices Rise With Tarriffs?

Many people think they understand why domestic prices rise with tariffs–domestic producers take advantage of reduced competition to jack up prices and increase their profits. The explanation seems cynical and sophisticated and its not entirely wrong but it misses deeper truths. Moreover, this “explanation” makes people think that an appropriate response to domestic firms raising prices is price controls and threats, which would make things worse. In fact, tariffs will increase domestic prices even in perfectly competitive industries. Let’s see why.

Suppose we tax imports of French and Italian wine. As a result, demand for California wine rises, and producers in Napa and Sonoma expand production to meet it. Here’s the key point: Expanding production without increasing costs is difficult, especially so for any big expansion in normal times.

To produce more, wine producers in Napa and Sonoma need more land. But the most productive, cost-effective land is already in use. Expansion forces producers onto less suitable land—land that’s either less productive for wine or more valuable for other purposes. Wine production competes with the production of olive oil, dairy and artisanal cheeses, heirloom vegetables, livestock, housing, tourism, and even geothermal energy (in Sonoma). Thus, as wine production expands, costs increases because opportunity costs increase. As wine production expands the price we pay is less production of other goods and services.

Thus, the fundamental reason domestic prices rise with tariffs is that expanding production must displace other high-value uses. The higher money cost reflects the opportunity cost—the value of the goods society forgoes, like olive oil and cheese, to produce more wine.

And the fundamental reason why trade is beneficial is that foreign producers are willing to send us wine in exchange for fewer resources than we would need to produce the wine ourselves. Put differently, we have two options: produce more wine domestically by diverting resources from olive oil and cheese, or produce more olive oil and cheese and trade some of it for foreign wine. The latter makes us wealthier when foreign producers have lower costs.

Tariffs reverse this logic. By pushing wine production back home, they force us to use more costly resources—to sacrifice more olive oil and cheese than necessary—to get the same wine. The result is a net loss of wealth.

Note that tariffs do not increase domestic production, they shift domestic production from one industry to another.

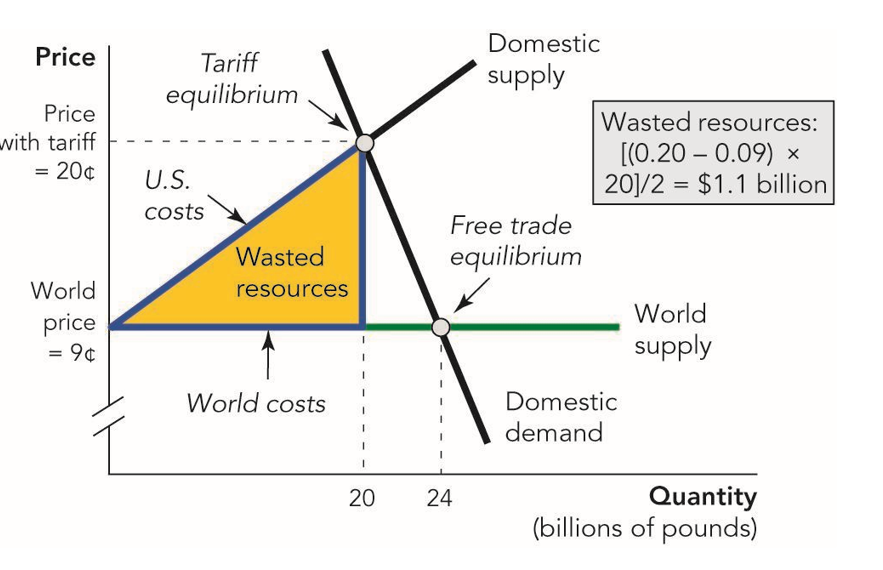

Here’s the diagram, taken from Modern Principles, using sugar as the example. Without the tariff, we could buy sugar at the world price of 9 cents per pound. The tariff pushes domestic production up to 20 billion pounds.

As the domestic sugar industry expands it pulls in resources from other industries. The value of those resources exceeds what we would have paid foreign producers. That excess cost is represented by the yellow area labeled wasted resources—the value of goods and services we gave up by redirecting resources to domestic sugar production instead of using them to produce other goods and services where we have a comparative advantage.

All of this, of course, is explained in Modern Principles, the best textbook for principles of economics. Needed now more than ever.

In Defense of Econ 101

People sometimes dismiss basic economic reasoning, “that’s just Econ 101!” yet most policymakers couldn’t pass the exam. Here’s an apropos bit from our excellent textbook, Modern Principles of Economics.

Do you shop at Giant, Safeway, or the Piggly Wiggly? If you do, you run a trade deficit with those stores. That is, you buy more goods from them than they buy from you (unless, of course, you work at one of these stores or sell them goods from your farm). The authors of this book also run a trade deficit with supermarkets. In fact, we have been running a trade deficit with Whole Foods for many years. Is our Whole Foods deficit a problem?

Our deficit with Whole Foods isn’t a problem because it’s balanced with a trade surplus with someone else. Who? You, the students, whether we teach you or whether you have bought our book. You buy more goods from us than we buy from you. We export education to you, but we do not import your goods and services. In short, we run a trade deficit with Whole Foods but a trade surplus with our students. In fact, it is only because we run a trade surplus with you that we can run a trade deficit with Whole Foods. Thanks!

The lesson is simple. Trade deficits and surpluses are to be found everywhere. Taken alone, the fact that the United States has a trade deficit with one country is not special cause for worry. Trade across countries is very much like trade across individuals. Not every person or every country can run a trade surplus all the time. Suddenly, a trade deficit does not seem so troublesome, even though the word “deficit” makes it sound like a problem or an economic shortcoming.

We continue on to discuss ” What if the United States runs a trade deficit not just with China or Japan or Mexico but with the world as a whole, as indeed it does? Is that a bad thing?”

Here’s a good Noah Smith piece if you want the details.

Federal Judge Rejects FDA Power Grab

In Don’t Let the FDA Regulate Lab Tests! and The New FDA and the Regulation of Laboratory Developed Tests I warned that the FDA’s power grab over laboratory developed tests was both unlawful and likely to result in deadly harm (as it did during COVID). Thus, I am pleased that a Federal judge has vacated the FDA’s rule entirely, writing:

…the text, structure, and history of the FDCA and CLIA make clear that FDA lacks the authority to regulate laboratory-developed test services.

…FDA’s asserted jurisdiction over laboratory-developed test services as “devices” under the FDCA defies bedrock principles of statutory interpretation, common sense, and longstanding industry practice.

The judge also noted some of the costs that I had pointed to:

…the Fifth Circuit has made clear that district courts should generally “nullify and revoke” illegal agency action, Braidwood, 104 F.4th at 951. The Court finds that such relief is appropriate here. The final rule will initially impact nearly 80,000 existing tests offered by almost 1,200 laboratories, and it will also affect about 10,013 new tests offered every year going forward. The estimated compliance costs for laboratories across the country will total well over $1 billion per year, and over the next two decades, FDA projects that total costs associated with the rule will range from $12.57 billion to $78.99 billion. FDA acknowledges that the enormous increased costs to laboratories may cause price increases and reduce the amount of revenue a laboratory can invest in creating and modifying tests.

… For these reasons, it is ORDERED that the Laboratory Plaintiffs’ Motions for Summary Judgment, (Dkt. #20, #27), are GRANTED. The final rule is hereby SET ASIDE and VACATED.

HHS head RFK Jr. should immediately instruct the FDA to halt any further efforts to regulate laboratory developed tests.

AI Discovers New Uses for Old Drugs

The NYTimes has an excellent piece by Kate Morgan on AI discovering new uses for old drugs:

A little over a year ago, Joseph Coates was told there was only one thing left to decide. Did he want to die at home, or in the hospital?

Coates, then 37 and living in Renton, Wash., was barely conscious. For months, he had been battling a rare blood disorder called POEMS syndrome, which had left him with numb hands and feet, an enlarged heart and failing kidneys. Every few days, doctors needed to drain liters of fluid from his abdomen. He became too sick to receive a stem cell transplant — one of the only treatments that could have put him into remission.

“I gave up,” he said. “I just thought the end was inevitable.”

But Coates’s girlfriend, Tara Theobald, wasn’t ready to quit. So she sent an email begging for help to a doctor in Philadelphia named David Fajgenbaum, whom the couple met a year earlier at a rare disease summit.

By the next morning, Dr. Fajgenbaum had replied, suggesting an unconventional combination of chemotherapy, immunotherapy and steroids previously untested as a treatment for Coates’s disorder.

Within a week, Coates was responding to treatment. In four months, he was healthy enough for a stem cell transplant. Today, he’s in remission.

The lifesaving drug regimen wasn’t thought up by the doctor, or any person. It had been spit out by an artificial intelligence model.

AI is excellent at combing through large amounts of data to find surprising connections.

Discovering new uses for old drugs has some big advantages and one disadvantage. A big advantage is that once a drug has been approved for some use it can be prescribed for any use–thus new uses of old drugs do not have to go through the lengthy and arduous FDA approval procedures. In essence, off-label uses have been safety-tested but not FDA efficacy-tested in the new use. I use this fact about off-label prescribing to evaluate the FDA. During COVID, for example, the British Recovery trial, discovered that the common drug, dexamethasone could reduce mortality by up to one-third in hospitalized patients on oxygen support that knowledge was immediately applied, saving millions of lives worldwide:

Within hours, the result was breaking news across the world and hospitals were adopting the drug into the standard care given to all patients with COVID-19. In the nine months following the discovery, dexamethasone saved an estimated one million lives worldwide.

New uses for old drugs are typically unpatentable, which helps keep them cheap—but the disadvantage is that this also weakens private incentives to discover them. While FDA trials for these new uses are often unnecessary, making development costs much lower, the lack of strong market protection can still deter investment. The FDA offers some limited exclusivity through programs like 505(b)(2), which grants temporary protection for new clinical trials or safety and efficacy data. These programs are hard to calibrate—balancing cost and reward is difficult—but likely provide some net benefits.

The NIH should continue prioritizing research into unpatentable treatments, as this is where the market is most challenged. More broadly, research on novel mechanisms to support non-patentable innovations is valuable. That said, I’m not overly concerned about under-investment in repurposing old drugs, especially as AI further reduces the cost of discovery.

Sell Floyd Bennett Field!

I’ve been shouting Sell! for many years. Perhaps now is the chance to do it. Here’s a recap:

The Federal Government owns more than half of Oregon, Utah, Nevada, Idaho and Alaska and it owns nearly half of California, Arizona, New Mexico and Wyoming. See the map (PDF) for more [N.B. the vast majority of this land is NOT parks, AT 2011]. It is time for a sale. Selling even some western land could raise hundreds of billions of dollars – perhaps trillions of dollars – for the Federal government at a time when the funds are badly needed and no one want to raise taxes. At the same time, a sale of western land would improve the efficiency of land allocation.

The Federal Government owns more than half of Oregon, Utah, Nevada, Idaho and Alaska and it owns nearly half of California, Arizona, New Mexico and Wyoming. See the map (PDF) for more [N.B. the vast majority of this land is NOT parks, AT 2011]. It is time for a sale. Selling even some western land could raise hundreds of billions of dollars – perhaps trillions of dollars – for the Federal government at a time when the funds are badly needed and no one want to raise taxes. At the same time, a sale of western land would improve the efficiency of land allocation.

But it’s not just federal lands in the West. Floyd Bennett Field is an old military airport in Brooklyn that hasn’t been used much since the 1970s. Today, it’s literally used as a training ground for sanitation drivers and to occasionally host radio-controlled airplane hobbyists.

In August 2023, state and federal officials reached an agreement to build a large shelter for migrants at Floyd Bennett Field, amid a citywide migrant housing crisis caused by a sharp increase in the number of asylum seekers traveling to the city. The shelter opened that November, but its remote location deterred many migrants. City officials announced plans in December 2024 to close the shelter.

Floyd Bennett Field is over 1000 acres and should be immediately sold to the highest bidder.

Brad Hargreaves on twitter has a good thread with some more examples.

Addendum: Here’s a NPR article (!) from 10 years ago that I am sure still applies even if not in all details:

Government estimates suggest there may be 77,000 empty or underutilized buildings across the country. Taxpayers own them, and even vacant, they’re expensive. The Office of Management and Budget believes these buildings could be costing taxpayers $1.7 billion a year.

…But doing something with these buildings is a complicated job. It turns out that the federal government does not know what it owns.

…even when an agency knows it has a building it would like to sell, bureaucratic hurdles limit it from doing so. No federal agency can sell anything unless it’s uncontaminated, asbestos-free and environmentally safe. Those are expensive fixes.

Then the agency has to make sure another one doesn’t want it. Then state and local governments get a crack at it, then nonprofits — and finally, a 25-year-old law requires the government to see if it could be used as a homeless shelter.

Many agencies just lock the doors and say forget it.

Peter Marks Forced Out at FDA

Peter Marks was key to President Trump’s greatest first-term achievement: Operation Warp Speed. In an emergency, he pushed the FDA to move faster—against every cultural and institutional incentive to go slow. He fought the system and won.

I had some hope that FDA commissioner Marty Makary would team with Marks at CBER. Makary understands that the FDA moves too slowly. He wrote in 2021:

COVID has given us a clear-eyed look at a broken Food and Drug Administration that’s mired in politics and red tape.

Americans can now see why medical advances often move at turtle speed. We need fresh leadership at the FDA to change the culture at the agency and promote scientific advancement, not hinder it.

This starts at the top. Our public health leaders have become too be accepting of the bureaucratic processes that would outrage a fresh eye. For example, last week the antiviral pill Molnupiravir was found to cut COVID hospitalizations in half and, remarkably, no one who got the drug died.

The irony is that Molnupiravir was developed a year ago. Do the math on the number of lives that could have been saved if health officials would have moved fast, allowing rolling trials with an evaluation of each infection and adverse event in real-time. Instead, we have a process that resembles a 7-part college application for each of the phase 1, 2, and 3 clinical trials.

A Makary-Marks team could have moved the FDA in a very promising direction. Unfortunately, disputes with RFK Jr proved too much. Marks was especially and deservedly outraged by the measles outbreak and the attempt to promote vitamins over vaccines:

“It has become clear that truth and transparency are not desired by the Secretary, but rather he wishes subservient confirmation of his misinformation and lies,” Marks wrote in a resignation letter referring to HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Thus, as of now, the FDA is moving in the wrong direction and Makary has lost an ally against RFK.

In other news, the firing of FDA staff is slowing down approvals, as I predicted it would.

The Madmen and the AIs

In Collaborating with AI Agents: Field Experiments on Teamwork, Productivity, and Performance Harang Ju and Sinan Aral (both at MIT) paired humans and AIs in a set of marketing tasks to generate some 11,138 ads for a large think tank. The basic story is that working with the AIs increased productivity substantially. Important, but not surprising. But here is where it gets wild:

[W]e manipulated the Big Five personality traits for each AI, independently setting them to high or low levels using P2 prompting (Jiang et al., 2023). This allows us to systematically investigate how AI personality traits influence collaborative work and whether there is heterogeneity in their effects based on the personality traits of the human collaborators, as measured through a pre-task survey.

In other words, they created AIs which were high and low on the “big 5” OCEAN metrics, Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness and Neuroticism and then they paired the different AIs with humans who were also rated on the big-5.

The results were quite amusing. For example, a neurotic AI tended to make a lot more copy edits unless paired with an agreeable human.

AI Alex: What do you think of this edit I made to the copy? Do you think it is any good?

Agreeable Alex: It’s great!

AI Alex: Really? Do you want me to try something else?

Agreeable Alex: Nah, let’s go with it!

AI Alex: Ok. 🙂

Similarly, if a highly conscientiousness AI and a highly conscientiousness human were paired together they exchanged a lot more messages.

It’s hard to generalize from one study to know exactly which AI-human teams will work best but we all know some teams just work better–every team needs a booster and a sceptic, for example– and the fact that we can manipulate AI personalities to match them with humans and even change the AI personalities over time suggests that AIs can improve productivity in ways going beyond the ability of the AI to complete a task.

Hat tip: John Horton.

Canada and America in Better Times

On November 4, 1979, a mob of radical university students and supporters of Ayatollah Khomeini, surged over the wall and occupied the US Embassy in Tehran. Fifty two Americans were taken hostage but six evaded capture. Hiding out for days, the escapees managed to contact Canadian diplomat John Sheardown and Canadian Ambassador Ken Taylor and asked for help. The Government of Canada reports:

Taylor didn’t hesitate. The Americans would be given shelter – the question was where. Because the Canadian Chancery was right downtown, it was far too dangerous. It would be better to split up the Americans. Taylor decided Sheardown should take three of hostages to his house, while he would house the others at the official residence. They would be described to staff as tourists visiting from Canada. Taylor immediately began drafting a cable for Ottawa.

…Taylor’s telegram set off a frenzy of consultation in the Department of External Affairs….Michael Shenstone, immediately concurred that Canada had no choice but to shelter the fugitives. Under-Secretary Allan Gotlieb agreed. Given the danger the Americans were in, he noted, there was “in all conscience…no alternative but to concur” despite the risk to Canadians and Canadian property.

The Minister, Flora MacDonald, could not be immediately reached as she was involved in a television interview. However, when finally informed of the situation, she agreed that Taylor must be permitted to act…[Prime Minister Joe Clark was pulled] from Question Period in the House of Commons, she briefed him on the situation and obtained his immediate go-ahead. Soon after, a telegram was sent to Tehran – Taylor could act to save the Americans. He was told that knowledge of the situation would be on a strict “need-to-know” basis.

The CIA reports:

The exfiltration task was daunting–the six Americans had no intelligence background; planning required extensive coordination within the US and Canadian governments; and failure not only threatened the safety of the hostages but also posed considerable risk of worldwide embarrassment to the US and Canada.

…After careful consideration of numerous options, the chosen plan began to take shape. Canadian Parliament agreed to grant Canadian passports to the six Americans. The CIA team together with an experienced motion-picture consultant devised a cover story so exotic that it would not likely draw suspicions–the production of a Hollywood movie.

The team set up a dummy company, “Studio Six Productions,” with offices on the old Columbia Studio lot formerly occupied by Michael Douglas, who had just completed producing The China Syndrome. This upstart company titled its new production “Argo” after the ship that Jason and the Argonauts sailed in rescuing the Golden Fleece from the many-headed dragon holding it captive in the sacred garden–much like the situation in Iran. The script had a Middle Eastern sci-fi theme that glorified Islam. The story line was intentionally complicated and difficult to decipher. Ads proclaimed Argo to be a “cosmic conflagration” written by Teresa Harris (the alias selected for one of the six awaiting exfiltration).

President Jimmy Carter approved the rescue operation.

The American diplomats escaped and all the Canadians quickly exited before the Iranian government realized what had happened. The Canadian embassy was closed. The story of the ex-filtration is told in the excellent movie, Argo, directed by and starring Ben Affleck. (The movie ups the American involvement for Hollywood but is still excellent.)

The CIA reports on what happened when the Americans made it back home:

News of the escape and Canada’s role quickly broke. Americans went wild in celebrating their appreciation to Canada and its Embassy staff. The maple leaf flew in a hundred cities and towns across the US. Billboards exclaimed “Thank you Canada!” Full-page newspaper ads expressed American’s thanks to its neighbors to the north. Thirty-thousand baseball fans cheered Canada’s Ambassador to Iran and the six rescued Americans, honored guests at a game in Yankee Stadium.

I remember this time well because my father, a professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Toronto, happened to be giving a talk in Boston when the news broke. He was immediately mobbed by appreciative Americans, who thanked him, clapped him on the back, and bought him drinks. My father was moved by the American response but was also somewhat bemused, considering he was also Iranian. (Though, in truth, my father was the ideal Canadian and he had his own experiences exfiltrating people from Iran—but that story remains Tabarrok classified.)

Argentina’s DOGE

Cato has a good summary of Deregulation in Argentina:

- The end of Argentina’s extensive rent controls has resulted in a tripling of the supply of rental apartments in Buenos Aires and a 30 percent drop in price.

- The new open-skies policy and the permission for small airplane owners to provide transportation services within Argentina has led to an increase in the number of airline services and routes operating within (and to and from) the country.

- Permitting Starlink and other companies to provide satellite internet services has given connectivity to large swaths of Argentina that had no such connection previously. Anecdotal evidence from a town in the remote northwestern province of Jujuy implies a 90 percent drop in the price of connectivity.

- The government repealed the “Buy Argentina” law similar to “Buy American” laws, and it repealed laws that required stores to stock their shelves according to specific rules governing which products, by which companies and which nationalities, could be displayed in which order and in which proportions.

- Over-the-counter medicines can now be sold not just by pharmacies but by other businesses as well. This has resulted in online sales and price drops.

- The elimination of an import-licensing scheme has led to a 20 percent drop in the price of clothing items and a 35 percent drop in the price of home appliances.

- The government ended the requirement that public employees purchase flights on the more expensive state airline and that other airlines cannot park their airplanes overnight at one of the main airports in Buenos Aires.

- In January, Sturzenegger announced a “revolutionary deregulation” of the export and import of food. All food that has been certified by countries with high sanitary standards can now be imported without further approval from, or registration with, the Argentine state. Food exports must now comply only with the regulations of the destination country and are unencumbered by domestic regulations.

Needless to say, America’s DOGE could learn something from Argentina:

Milei’s task of turning Argentina once again into one of the freest and most prosperous countries in the world is herculean. But deregulation plays a key role in achieving that goal, and despite the reform agenda being far from complete, Milei has already exceeded most people’s expectations. His deregulations are cutting costs, increasing economic freedom, reducing opportunities for corruption, stimulating growth, and helping to overturn a failed and corrupt political system. Because of the scope, method, and extent of its deregulations, Argentina is setting an example for an overregulated world.

What Follows from Lab Leak?

Does it matter whether SARS-CoV-2 leaked from a lab in Wuhan or had natural zoonotic origins? I think on the margin it does matter.

First, and most importantly, the higher the probability that SARS-CoV-2 leaked from a lab the higher the probability we should expect another pandemic.* Research at Wuhan was not especially unusual or high-tech. Modifying viruses such as coronaviruses (e.g., inserting spike proteins, adapting receptor-binding domains) is common practice in virology research and gain-of-function experiments with viruses have been widely conducted. Thus, manufacturing a virus capable of killing ~20 million human beings or more is well within the capability of say ~500-1000 labs worldwide. The number of such labs is growing in number and such research is becoming less costly and easier to conduct. Thus, lab-leak means the risks are larger than we thought and increasing.

A higher probability of a pandemic raises the value of many ideas that I and others have discussed such as worldwide wastewater surveillance, developing vaccine libraries and keeping vaccine production lines warm so that we could be ready to go with a new vaccine within 100 days. I want to focus, however, on what new ideas are suggested by lab-leak. Among these are the following.

Given the risks, a “Biological IAEA” with similar authority as the International Atomic Energy Agency to conduct unannounced inspections at high-containment labs does not seem outlandish. (Indeed the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists are about the only people to have begun to study the issue of pandemic lab risk.) Under the Biological Weapons Convention such authority already exists but it has never been used for inspections–mostly because of opposition by the United States–and because the meaning of biological weapon is unclear, as pretty much everything can be considered dual use. Notice, however, that nuclear weapons have killed ~200,000 people while accidental lab leak has probably killed tens of millions of people. (And COVID is not the only example of deadly lab leak.) Thus, we should consider revising the Biological Weapons Convention to something like a Biological Dangers Convention.

BSL3 and especially BSL4 safety procedures are very rigorous, thus the issue is not primarily that we need more regulation of these labs but rather to make sure that high-risk research isn’t conducted under weaker conditions. Gain of function research of viruses with pandemic potential (e.g. those with potential aerosol transmissibility) should be considered high-risk and only conducted when it passes a review and is done under BSL3 or BSL4 conditions. Making this credible may not be that difficult because most scientists want to publish. Thus, journals should require documentation of biosafety practices as part of manuscript submission and no journal should publish research that was done under inappropriate conditions. A coordinated approach among major journals (e.g., Nature, Science, Cell, Lancet) and funders (e.g. NIH, Wellcome Trust) can make this credible.

I’m more regulation-averse than most, and tradeoffs exist, but COVID-19’s global economic cost—estimated in the tens of trillions—so vastly outweighs the comparatively minor cost of upgrading global BSL-2 labs and improving monitoring that there is clear room for making everyone safer without compromising research. Incredibly, five years after the crisis and there has be no change in biosafety regulation, none. That seems crazy.

Many people convinced of lab leak instinctively gravitate toward blame and reparations, which is understandable but not necessarily productive. Blame provokes defensiveness, leading individuals and institutions to obscure evidence and reject accountability. Anesthesiologists and physicians have leaned towards a less-punitive, systems-oriented approach. Instead of assigning blame, they focus in Morbidity and Mortality Conferences on openly analyzing mistakes, sharing knowledge, and redesigning procedures to prevent future harm. This method encourages candid reporting and learning. At its best a systems approach transforms mistakes into opportunities for widespread improvement.

If we can move research up from BSL2 to BSL3 and BSL4 labs we can also do relatively simple things to decrease the risks coming from those labs. For example, let’s not put BSL4 labs in major population centers or in the middle of a hurricane prone regions. We can also, for example, investigate which biosafety procedures are most effective and increase research into safer alternatives—such as surrogate or simulation systems—to reduce reliance on replication-competent pathogens.

The good news is that improving biosafety is highly tractable. The number of labs, researchers, and institutions involved is relatively small, making targeted reforms feasible. Both the United States and China were deeply involved in research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, suggesting at least the possibility of cooperation—however remote it may seem right now.

Shared risk could be the basis for shared responsibility.

Bayesian addendum *: A higher probability of a lab-leak should also reduce the probability of zoonotic origin but the latter is an already known risk and COVID doesn’t add much to our prior while the former is new and so the net probability is positive. In other words, the discovery of a relatively new source of risk increases our estimate of total risk.

Maui is Not Abundant

City Journal: A year and a half since fires devastated the historic town of Lahaina on the island of Maui, Hawaii, only six houses have been rebuilt—six out of more than 2,000.

Why is the recovery effort taking so long? Initially, the biggest hurdles were the pace of debris removal and damage litigation. Both were overcome only last month. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers cleared the final lots on February 19, while the Hawaiian Supreme Court ruled that a $4 billion settlement for victims can begin to move forward.

The main challenge now is dealing with a crushing permitting regime that slows or outright bans construction. But local political dysfunction has discouraged state and local leaders from taking emergency action to cut through this red tape.

Many of the buildings are illegal to rebuild under the current zoning laws. CA at least exempted reconstruction from California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) and Coastal Waters Act review.

China’s Medicines are Saving American Lives

The Economist reports that China is now the second largest producer of new pharmaceuticals, after the United States.

China has long been known for churning out generic drugs, supplying raw ingredients and managing clinical trials for the pharmaceutical world. But its drugmakers are now also at the cutting edge, producing innovative medicines that are cheaper than the ones they compete with.

… In September last year an experimental drug did what none had done before. In late-stage trials for non-small cell lung cancer, it nearly doubled the time patients lived without the disease getting worse—to 11.1 months, compared with 5.8 months for Keytruda. The results were stunning. So too was the nationality of the biotech company behind them. Akeso is Chinese.

This is exactly what I predicted in my TED talk and it’s great news! As I said then:

Ideas have this amazing property. Thomas Jefferson said “He who receives an idea from me receives instruction himself, without lessening mine. As he who lights his candle at mine receives light without darkening me.”

Now think about the following: if China and India were as rich as the United States is today, the market for cancer drugs would be eight times larger than it is now. Now we are not there yet, but it is happening. As other countries become richer the demand for these pharmaceuticals is going to increase tremendously. And that means an increase incentive to do research and development, which benefits everyone in the world. Larger markets increase the incentive to produce all kinds of ideas, whether it’s software, whether it’s a computer chip, whether it’s a new design.

Well if larger markets increase the incentive to produce new ideas, how do we maximize that incentive?

It’s by having one world market, by globalizing the world. Ideas are meant to be shared.

One idea, one world, one market.

Sadly, some of us are losing sight of the immense benefits of a global market. Another example of the great forgetting.

As Girard predicted, China’s growing similarity to the U.S. has fueled conflict and rivalry. But if managed properly, rivalry can be positive-sum. A rich China benefits us far more than a poor China—including by creating new cancer medicines that save American lives.

Hat tip: Cremieux.

Public Choice Outreach Conference!

The annual Public Choice Outreach Conference is a crash course in public choice. The conference is designed for undergraduates and graduates in a wide variety of fields. It’s entirely free. Indeed scholarships are available! The conference will be held Friday May 30-Sunday June 1, 2025, near Washington, DC in Arlington, VA. Lots of great speakers. More details in the poster. Please encourage your students to apply.

What Did We Learn From Torturing Babies?

As late as the 1980s it was widely believed that babies do not feel pain. You might think that this was an absurd thing to believe given that babies cry and exhibit all the features of pain and pain avoidance. Yet, for much of the 19th and 20th centuries, the straightforward sensory evidence was dismissed as “pre-scientific” by the medical and scientific establishment. Babies were thought to be lower-evolved beings whose brains were not yet developed enough to feel pain, at least not in the way that older children and adults feel pain. Crying and pain avoidance were dismissed as simply reflexive. Indeed, babies were thought to be more like animals than reasoning beings and Descartes had told us that an animal’s cries were of no more import than the grinding of gears in a mechanical automata. There was very little evidence for this theory beyond some gesturing’s towards myelin sheathing. But anyone who doubted the theory was told that there was “no evidence” that babies feel pain (the conflation of no evidence with evidence of no effect).

Most disturbingly, the theory that babies don’t feel pain wasn’t just an error of science or philosophy—it shaped medical practice. It was routine for babies undergoing medical procedures to be medically paralyzed but not anesthetized. In one now infamous 1985 case an open heart operation was performed on a baby without any anesthesia (n.b. the link is hard reading). Parents were shocked when they discovered that this was standard practice. Publicity from the case and a key review paper in 1987 led the American Academy of Pediatrics to declare it unethical to operate on newborns without anesthesia.

In short, we tortured babies under the theory that they were not conscious of pain. What can we learn from this? One lesson is humility about consciousness. Consciousness and the capacity to suffer can exist in forms once assumed to be insensate. When assessing the consciousness of a newborn, an animal, or an intelligent machine, we should weigh observable and circumstantial evidence and not just abstract theory. If we must err, let us err on the side of compassion.

Claims that X cannot feel or think because Y should be met with skepticism—especially when X is screaming and telling you different. Theory may convince you that animals or AIs are not conscious but do you want to torture more babies? Be humble.

We should be especially humble when the beings in question are very different from ourselves. If we can be wrong about animals, if we can be wrong about other people, if we can be wrong about our own babies then we can be very wrong about AIs. The burden of proof should not fall on the suffering being to prove its pain; rather, the onus is on us to justify why we would ever withhold compassion.

Hat tip: Jim Ward for discussion.

The Shortage that Increased Ozempic Supply

It sometimes happens that a patient needs a non-commercially-available form of a drug, a different dosage or a specific ingredient added or removed depending on the patient’s needs. Compounding pharmacies are allowed to produce these drugs without FDA approval. Moreover, since the production is small-scale and bespoke the compounded drugs are basically immune from any patent infringement claims. The FDA, however, also has an oddly sensible rule that says when a drug is in shortage they will allow it be compounded, even when the compounded version is identical to the commercial version.

The shortage rule was meant to cover rare drugs but when demand for the GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic and Zepbound skyrocketed, the FDA declared a shortage and big compounders jumped into the market offering these drugs at greatly reduced prices. Moreover, the compounders advertised heavily and made it very easy to get a “prescription.” Thus, the GLP-1 compounders radically changed the usual story where the patient asks the compounder to produce a small amount of a bespoke drug. Instead the compounders were selling drugs to millions of patients.

Thus, as a result of the shortage rule, the shortage led to increased supply! The shortage has now ended, however, which means you can expect to see many fewer Hims and Hers ads.

Scott Alexander makes an interesting point in regard to this whole episode:

I think the past two years have been a fun experiment in semi-free-market medicine. I don’t mean the patent violations – it’s no surprise that you can sell drugs cheap if you violate the patent – I mean everything else. For the past three years, ~2 million people have taken complex peptides provided direct-to-consumer by a less-regulated supply chain, with barely a fig leaf of medical oversight, and it went great. There were no more side effects than any other medication. People who wanted to lose weight lost weight. And patients had a more convenient time than if they’d had to wait for the official supply chain to meet demand, get a real doctor, spend thousands of dollars on doctors’ visits, apply for insurance coverage, and go to a pharmacy every few weeks to pick up their next prescription. Now pharma companies have noticed and are working on patent-compliant versions of the same idea. Hopefully there will be more creative business models like this one in the future.

The GLP-1 drugs are complex peptides and the compounding pharmacies weren’t perfect. Nevertheless, I agree with Scott that, as with the off-label market, the experiment in relaxed FDA regulation was impressive and it does provide a window onto what a world with less FDA regulation would look like.

Hat tip: Jonathan Meer.