Creative Stagnation

Legislation requiring cars and trucks, including electric vehicles, to have AM radios easily cleared a House committee Wednesday, although it could run into opposition going forward.

H.R. 979, the “AM Radio for Every Vehicle Act,” would require the Department of Transportation to enforce the mandate through a rulemaking. It passed the Energy and Commerce Committee by a 50-1 vote. Rep. Jay Obernolte (R-Calif.) was the only “no.”

What’s next—mandating 8-track players in every car? Fax machines in every home? Floppy disks in every laptop? If Congress actually cared about emergency communication, it would strengthen cellular networks, not cling to obsolete technology. Congress is a den of old busybodies.

Hat tip: Nick Gillespie.

Addendum: If AM radio is so valuable for emergencies then the market will provide or you could, you know, put an AM radio in your glove box. No need for a mandate. We already have FM, broadcast TV, cable, satellite, cell, and Wireless Emergency Alerts; resilience can be met without specifying AM hardware.

Here Comes the Sun—If We Let It: Cutting Tariffs and Red Tape for Rooftop Solar

Australia has so much rooftop solar power that some states are offering free electricity during peak hours:

TechCrunch: For years, Australians have been been installing solar panels at a rapid clip. Now that investment is paying off.

The Australian government announced this week that electricity customers in three states will get free electricity for up to three hours per day starting in July 2026.

Solar power has boomed in Australia in recent years. Rooftop solar installations cost about $840 (U.S.) per kilowatt of capacity before rebates, about a third of what U.S. households pay. As a result, more than one in three Australian homes have solar panels on their roof.

Why is rooftop solar adoption in the U.S. lagging behind Australia, Europe, and much of Asia? Australia has roughly as many rooftop installations as the entire United States, despite having less than a tenth of its population.

First, tariffs. U.S. tariffs on imported solar panels mean American buyers pay double to triple the global market rate.

Second, permits. The U.S. permitting process is slow, fragmented, and expensive. In Australia, no permit is required for a standard installation—you simply notify the distributor and have an accredited installer certify safety. In Australia, a rooftop solar panel is treated like an appliance; in the U.S., it’s treated like a mini power plant. Germany takes a similar approach to Australia, with national standards and an “as-of-right” presumption for rooftop solar that removes red tape.

By contrast, the U.S. system involves multiple layers of approval—building and electrical permits, several inspections, and a Permission-to-Operate from the local utility, which may not be eager to speed things up just to lose your business. Moreover, each of thousands of jurisdictions has different requirements, creating long delays and high costs.

High costs suppress adoption, limiting economies of scale and forcing installers to spend more on sales than installation. Yet Australia and Germany are not so different from the United States—they simply made solar easy. If the U.S. eliminated tariffs, standardized/nationalized rules, and accelerated approvals, rooftop solar would take off, costs would fall, and innovation would follow.

The benefits extend beyond cheaper power. Distributed rooftop generation makes the grid more resilient. Streamlining solar policy would thus cut energy costs, strengthen protection against disasters and disruptions, and speed the transition to a future with more abundant and cleaner power.

The MR Podcast: Our Favorite Models, Session 3: Compensating Differentials and Selective Incentives

On The Marginal Revolution Podcast this week, Tyler and I discuss compensating differentials and Olsonian selective incentives. Here’s one bit:

If you think about the gender wage gap, it’s sometimes said that women earn—it varies—80 cents for every dollar that a man earns. That doesn’t control for anything. Once you control for education and skill and so forth, this gets smaller. Then you also have to control for these quite difficult, elusive sometimes, job amenities. Claudia Goldin, for example, has pointed out that men are much more willing to take jobs requiring inflexible hours.

COWEN: And longer hours, too.

TABARROK: Longer hours and inflexible hours, where your hours are less under your control. That’s what I mean by inflexible. For example, in one study of train and bus drivers, the train and bus drivers are paid equally by gender. There’s no differences whatsoever in what they’re paid on an hourly basis. It turns out that the male drivers, their wages, their returns are much higher because they take a lot more overtime. They take 83% more overtime than their female colleagues. They’re much more likely to accept an overtime shift, which pays time and a half. The male workers also take fewer unpaid hours off. The male salaries on a yearly basis end up being higher, even though males and females are paid equally.

Now, you can roll this back and say that’s because of the unfair demands on women of childcare or something like that, but it’s not a market discrimination. It’s not market discrimination. It’s a compensating differential. Males earn more because they’re more willing to take the inflexible overtime hours and so forth.

One of the most interesting ones is that Uber drivers, male drivers earn a little bit more. Now, obviously, there’s no gender difference whatsoever in how the drivers are paid. It just turns out that male drivers just drive a little bit faster.

COWEN: I’ve noticed this, by the way, when I take Ubers.

TABARROK: On an annual basis, they make about 7% more. Now, again, it’s not entirely obvious that this is even better for the male drivers. Maybe they’re taking a little bit more risk. Maybe they’re a little bit more likely to get into an accident as well.

….COWEN: …Someone gets the short end of the stick. Not only women, but maybe women on average would be more likely to suffer.

TABARROK: I’m not sure it’s the short end of the stick, though I agree with increasing returns, that the people who work longer hours will also earn higher salaries and maybe have plush offices and so forth. Let me put it this way. One of the things which I think the feminism story sometimes gets a little bit wrong is to actually underestimate the value that women get, and that men can get as well, of childcare, of looking after kids, of spending more time at home, or spending more time doing childcare. That can be extremely valuable. At the end of life, who writes on their tombstone, “I wish I could have worked more”?

COWEN: You’re looking at one.

TABARROK: Present company excepted.

Here’s the episode. Subscribe now to take a small step toward a much better world: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube.

How Cultural Diversity Drives Innovation

It is hardly possible to overrate the value…of placing human beings in contact with persons dissimilar to themselves, and with modes of thought and action unlike those with which they are familiar….Such communication has always been, and is peculiarly in the present age, one of the primary sources of progress.

Mill had in mind the civilizing force of commerce but the idea is far more general. My colleague Jonathan Schulz with Max Posch and Joe Henrich have a novel and important test of the idea in a paper forthcoming in the JPE: How Cultural Diversity Drives Innovation (WP; SSRN). They show that the more diverse a county, as measured by surnames, the more ideas and the more novel ideas were patented in that county.

We show that innovation in U.S. counties from 1850 to 1940 was propelled by shifts in the local social structure, as captured using the diversity of surnames. Leveraging quasi-random variation in counties’ surnames—stemming from the interplay between historical fluctuations in immigration and local factors that attract immigrants—we find that more diverse social structures increased both the quantity and quality of patents, likely because they spurred interactions among individuals with different skills and perspectives. The results suggest that the free flow of information between diverse minds drives innovation and contributed to the emergence of the U.S. as a global innovation hub.

David Brooks on the New Right

Excellent David Brooks column on how the right has adopted the theories and tools of the left:

As so many have noted, MAGA is identity politics for white people. It turns out that identity politics is more effective when your group is in the majority.

…Last year, a writer named James Lindsay cribbed language from “The Communist Manifesto,” changed its valences so that they were right wing and submitted it to a conservative publication called The American Reformer. The editors, unaware of the provenance, were happy to print it. When the hoax was revealed, they were still happy! The right is now eager to embrace the ideas that led to tyranny, the gulag and Mao’s Cultural Revolution. Interestingly, the right didn’t take the leftist ideas that were intended to build something; they took just the ideas intended to destroy.

Read the whole thing.

Time to Privatize U.S. Air Traffic Control—Copy Canada’s Model

Yesterday, the FAA grounded flights at Reagan (DCA) because there weren’t enough air traffic controllers. By mid‑afternoon, thousands of flights were delayed nationwide. The same thing is happening at major airports across the country.

The proximate cause is that the FAA is short about ~3,500 controllers, forcing the rest to work mandatory overtime, six days a week, and now, during the shutdown, sometimes without pay! The more fundamental problem is that we have a poorly incentivized system. It’s absurd that a mission‑critical service is financed by annual appropriations subject to political failure. We need to remove the politics.

Canada fixed this in 1996 by spinning off air navigation services to NAV CANADA, a private, non‑profit utility funded by user fees, not taxes. Safety regulation stayed with the government; operations moved to a professionally governed, bond‑financed utility with multi‑year budgets. NAV Canada has been instrumental in moving Canada to more accurate and safer satellite-based navigation, rather than relying on ground-based radar as in the US.

NAV CANADA – in conjunction with the United Kingdom’s NATS – was the first in the world to deploy space-based ADS-B, by implementing it in 2019 over the North Atlantic, the world’s busiest oceanic airspace.

NAV CANADA was also the first air navigation service provider worldwide to implement space-based ADS-B in its domestic airspace.

Meanwhile, America’s NextGen has delivered a fraction of promised benefits, years late and over budget. As the Office of Inspector General reports:

Lengthy delays and cost growth have been a recurring feature of FAA’s modernization efforts through the course of NextGen’s over 20-year lifespan. FAA faced significant challenges throughout NextGen’s development and implementation phases that resulted in delaying or reducing benefits and delivering fewer capabilities than expected. While NextGen programs and capabilities have delivered some benefits in the form of more efficient air traffic management and reduced flight delays and airline operating costs, as of December 2024, FAA had achieved only about 16 percent of NextGen’s total expected benefits.

Airlines bleed money when planes idle, gates clog, and crews time out. The airlines have every reason to demand reliability, capacity, and modernization—Congress does not. Thus, fund air traffic control with user fees paid by those who depend on performance. Put the airline executives on the board of the non-profit, as in Canada. Give them the power to tax themselves to benefit themselves.

Align power with incentives and performance will follow.

The Game Theory of House of Dynamite

In the comments to yesterday’s review of House of Dynamite, some people balked at the movie’s central premise: that the U.S. has to decide—immediately—whether to launch a retaliatory nuclear strike. “Why not wait?” they asked. “Why not take a few days, even a few months, to figure out who actually fired the missile?”

That question even came up at GMU lunch, so it’s worth explaining why the time pressure is realistic. No real spoilers.

The U.S. doesn’t know whether the missile came from China, Russia, or North Korea and that seems to weigh in favor of waiting and gathering evidence. But here’s the problem: Russia, China, and North Korea don’t know what the U.S. knows. Suppose Russia thinks the U.S. believes Russia launched the strike. Then Russia expects retaliation. Expecting retaliation makes it rational for Russia to attack first. So Russia mobilizes.

The mobilization convinces the U.S. that Russia is preparing to attack—so now it’s rational for the U.S. to strike first. Which, of course, confirms Russia’s fears and pushes them closer to launching.

Even if the U.S. doesn’t actually think Russia fired the missile, it might still attack. Why? Because it believes that Russia believes the U.S. believes Russia did.

In this belief spiral, delay brings doom not clarity. In the film, Jake Baerington tries to break the doom loop but the logic is strong and amplified by speed and fear. Breaking the loop isn’t impossible, but as the movie suggests, it requires an act that cuts against immediate self-interest.

What to Watch

A House of Dynamite (Netflix) is an expertly crafted political thriller about living 18 minutes from nuclear annihilation. Directed by Kathryn Bigelow, it shares thematic DNA with two of her previous films, The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty. (Bigelow also directed the cult classic Point Break and the underrated Strange Days). The film tightens the tension in the first 18 minutes, releases it just enough to breathe, then resets and winds you up again—and then again. There is no climax. That frustrates some viewers, but the ending makes the point: the film is fiction but we are the ones living in a house of dynamite. Nuclear war is underrated as a problem–see previous MR posts. The film is technically and politically well researched, which is one reason the Pentagon is trying to pushback on some figures. If HOD is to be charged with a lack of realism, it’s in the competency of the within 18-minute response (although there are some excellent phone scenes.)

Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere isn’t a conventional rock biopic. It focuses on the making of Nebraska, Springsteen’s bleakest and most intimate album—a solo acoustic recorded at his home in New Jersey on a cassette. Nebraska’s songs portray not the merely unlucky, but the damned: people who drag others down with them.

I saw her standing on her front lawn

Just a-twirling her baton

Me and her went for a ride, sir

And ten innocent people died…I can’t say that I’m sorry

For the things that we done

At least for a little while, sir

Me and her, we had us some fun

Springsteen was depressed at the time. The film has three love stories, the first and least important is between Springsteen and his then girlfriend. The second is Springsteen’s relationship with his troubled father. The third is with his manager, Jon Landau. We should all be so lucky to have someone who loves us as much as Landau loved Springsteen.

Jeremy Allen White, as Springsteen, gives a strong performance; in some shots he looks uncannily like him. He sings most of the songs himself and excels on the Nebraska material, though he can’t match Springsteen’s power and electricity on the brief E Street Band sequences. Jeremy Strong is excellent as Landau.

I liked Deliver Me from Nowhere, but it doesn’t demand a big screen, you can watch at home.

It’s not a movie, but for my money Wings for Wheels: The Making of “Born to Run”, included with the 30th-anniversary edition of BTR, remains the definitive portrait of Springsteen at work. It shows Springsteen driving the E Street Band through take after take, unrelenting and exhausting, in pursuit of the sound in his head—a great study in creative obsession. Pairs well with the very different process documented in Peter Jackson’s Get Back.

Privatizing Law Enforcement: The Economics of Whistleblowing

The False Claims Act lets whistleblowers sue private firms on behalf of the federal government. In exchange for uncovering fraud and bringing the case, whistleblowers can receive up to 30% of any recovered funds. My work on bounty hunters made me appreciate the idea of private incentives in the service of public goals but a recent paper by Jetson Leder-Luis quantifies the value of the False Claims Act.

Leder-Luis looks at Medicare fraud. Because the government depends heavily on medical providers to accurately report the services they deliver, Medicare is vulnerable to misbilling. It helps, therefore, to have an insider willing to spill the beans. Moreover, the amounts involved are very large giving whistleblowers strong incentives. One notable case, for example, involved manipulating cost reports in order to receive extra payments for “outliers,” unusually expensive patients.

On November 4, 2002, Tenet Healthcare, a large investor-owned hospital company, was sued under the False Claims Act for manipulating its cost reports in order to illicitly receive additional outlier payments. This lawsuit was settled in June 2006, with Tenet paying $788 million to resolve these allegations without admission of guilt.

The savings from the defendants alone were significant but Leder-Luis looks for the deterrent effect—the reduction in fraud beyond the firms directly penalized. He finds that after the Tenet case, outlier payments fell sharply relative to comparable categories, even at hospitals that were never sued.

Tenet settled the outlier case for $788 million, but outlier payments were around $500 million per month at the time of the lawsuit and declined by more than half following litigation. This indicates that outlier payment manipulation was widespread… for controls, I consider the other broad types of payments made by Medicare that are of comparable scale, including durable medical equipment, home health care, hospice care, nursing care, and disproportionate share payments for hospitals that serve many low-income patients.

…the five-year discounted deterrence measurement for the outlier payments computed is $17.46 billion, which is roughly nineten times the total settlement value of the outlier whistleblowing lawsuits of $923 million.

[Overall]…I analyze four case studies for which whistleblowers recovered $1.9 billion in federal funds. I estimate that these lawsuits generated $18.9 billion in specific deterrence effects. In contrast, public costs for all lawsuits filed in 2018 amounted to less than $108.5 million, and total whistleblower payouts for all cases since 1986 have totaled $4.29 billion. Just the few large whistleblowing cases I analyze have more than paid for the public costs of the entire whistleblowing program over its life span, indicating a very high return on investment to the FCA.

As an aside, Leder-Luis uses synthetic control but allows the controls to come from different time periods. I’m less enthused by the method because it introduces another free parameter but given the large gains at small cost from the False Claims Act, I don’t doubt the conclusion:

The results of this analysis suggest that privatization is a highly effective way to combat fraud. Whistleblowing and private enforcement have strong deterrence effects and relatively low costs, overcoming the limited incentives for government-conducted antifraud enforcement. A major benefit of the False Claims Act is not just the information provided by the whistleblower but also the profit motive it provides for whistleblowers to root out fraud.

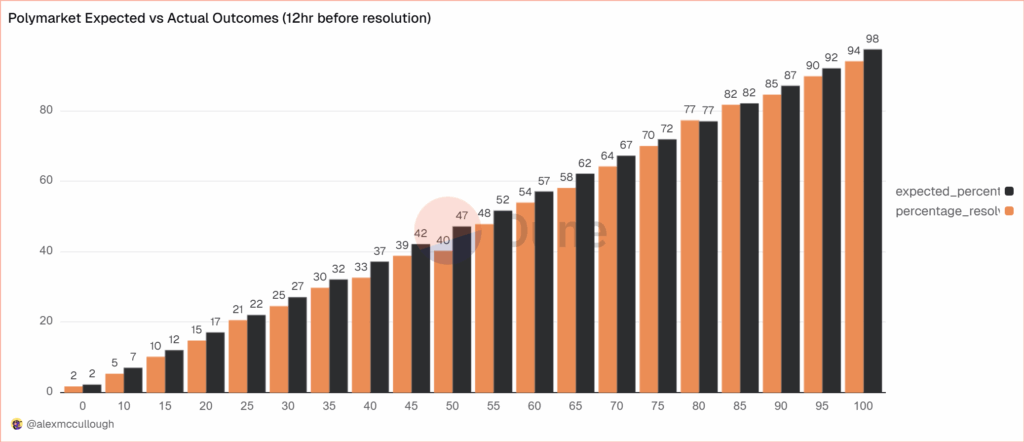

Prediction Markets Are Very Accurate

alexmccullough at Dune has a very good post on the accuracy of Polymarket prediction markets. First, how do we measure accuracy? Suppose a prediction market predicts an event will happen with p=.7, i.e. a 70% probability. The event happens. How do we score this prediction? A common method is the Brier Score which is the mean squared difference from the actual outcome. In this case the Brier Score is (0.70−1)2 = 0.09. Notice that if the prediction market had predicted the event would have happened with 90% probability, a better prediction, then the Brier Score would have been (0.90−1)2 = 0.01 a lower number. If the event had not happened then the Brier Score for a 70% prediction would have been (0.70−0)2 = 0.49, a higher number. Thus, a lower Brier Score is better.

Across some 90,000 predictions the Polymarket Brier Score for a 12 hour ahead prediction is .0581. As Alex notes:

A brier score below 0.125 is good, and below 0.1 is great. Polymarket’s total score is excellent, and puts it on par with the best prediction model’s in existence… Sports betting lines tend to average a brier score of between .18-.22.

Brier Scores have been widely used to measure weather forecasts. A state of the art 12 hour ahead forecast of rain, for example, might have a Brier Score of .0.05 – 0.12 so if Polymarket suggest a metaphorical umbrella you would be wise to listen.

Moreover, highly liquid markets are even more accurate.

Even markets with low liquidity have good brier scores below 0.1, but markets with more than $1m in total trading volume have scores of 0.0256 12 hours prior to resolution and 0.0159 a day prior. It’s hard to overstate how impressive that is.

There are, however, some small but systematic errors. The following bar chart splits events into 20 buckets of 5% each so the first bucket covers events that were predicted to happen 0-5% of the time and the last bucket covers events that were predicted to happen 95-100% of the time. The black bar gives the predicted probability, the orange bar the actual frequencies. As expected, events which are predicted to happen more often do happen more often with a very nice progression. Note, however, that the predicted probability is almost always slightly higher than the actual frequency. This means that people are paying a bit too much. It’s unclear whether this is due to market design issues such as the greater difficult of shorting or something about the Automated Market Makers or due to psychological factors such as favorite bias. Thus, some room for improvement but very impressive overall.

The MR Podcast: Our Favorite Models, Session 2: The Baumol Effect

On The Marginal Revolution Podcast this week we continue discussing some of our favorite models with a whole episode on the Baumol effect (with a sideline into the Linder effect). I say our favorite models, but the Baumol Effect is not one of Tyler’s favorite models! I thought this was a funny section:

TABARROK: When you look at all of these multiple sectors, the repair sector, repairing of clothing, repairing of shoes, repairing of cars, repairing of people, it’s not an accident that these are all the same thing. Healthcare is the repairing of people. Repair services, in general, have gone up because it’s a very labor-intensive area of the economy. It’s all the same thing. That’s why I like the Baumol effect, because it explains a very wide set of phenomena.

COWEN: A lot of things are easier to repair than they used to be, just to be clear. You just buy a new one.

TABARROK: That’s my point. You just buy a new one.

COWEN: It’s so cheap to buy a new one.

TABARROK: Exactly. The new one is manufactured. That’s the whole point, is the new one takes a lot less labor. The repair is much more labor intensive than the actual production of the good. When you actually produce the good, it’s on a factory floor, and you’ve got robots, and they’re all going through da-da-da-da-da-da-da. Repair services, it’s unique.

COWEN: I think you’re not being subjectivist enough in terms of how you define the service. The service for me, if my CD player breaks, is getting a stream of music again. That is much easier now and cheaper than it used to be. If you define the service as the repair, well, okay, you’re ruling out a lot of technological progress. You can think of just diversity of sources of music as a very close substitute for this narrow vision of repair. Again, from the consumer’s point of view, productivity on “repair” has been phenomenal.

TABARROK: That is a consequence of the Baumol effect, not a denial of the Baumol effect. Because of the Baumol effect, repair becomes much more expensive over time, so people look for substitutes. Yes, we have substituted into producing new goods. It works both ways. The new goods are becoming cheaper to manufacture. We are less interested in repair. Repair is becoming more expensive. We’re more interested in the new goods. That’s a consequence of the Baumol effect.

You can’t just say, “Oh, look, we solved the repair problem by throwing things out. Now we don’t have to worry about repairs.” Yes, that’s because repair became so much more expensive. A shift in relative prices caused people to innovate. I’m not saying that innovation doesn’t happen. One of the reasons that innovation happens is because the relative price of repair services is going up.

COWEN: That’s a minor effect. It’s not the case that, oh, I started listening to YouTube because it became too expensive to repair my CD player. It might be a very modest effect. Mostly, there’s technological progress. YouTube, Spotify, and other services come along, Amazon one-day delivery, whatever else. For the thing consumers care about, which is never what Baumol wanted to talk about. He always wanted to fixate on the physical properties of the goods, like the anti-Austrian he was.

It’s just like, oh, there’s been a lot of progress. It takes the form of networks with very complex capital and labor interactions. It’s very hard to even tease out what is truly capital intensive, truly labor intensive. You see this with the AI companies, all very mixed together. That just is another way of looking at why the predictions are so hard. You can only get the prediction simple by focusing very simply on these nonsubjectivist, noneconomic, physical notions of what the good has to be.

TABARROK: I think there’s too much mood affiliation there, Tyler.

COWEN: There’s not enough Kelvin Lancaster in Baumol.

Here’s the episode. Subscribe now to take a small step toward a much better world: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube.

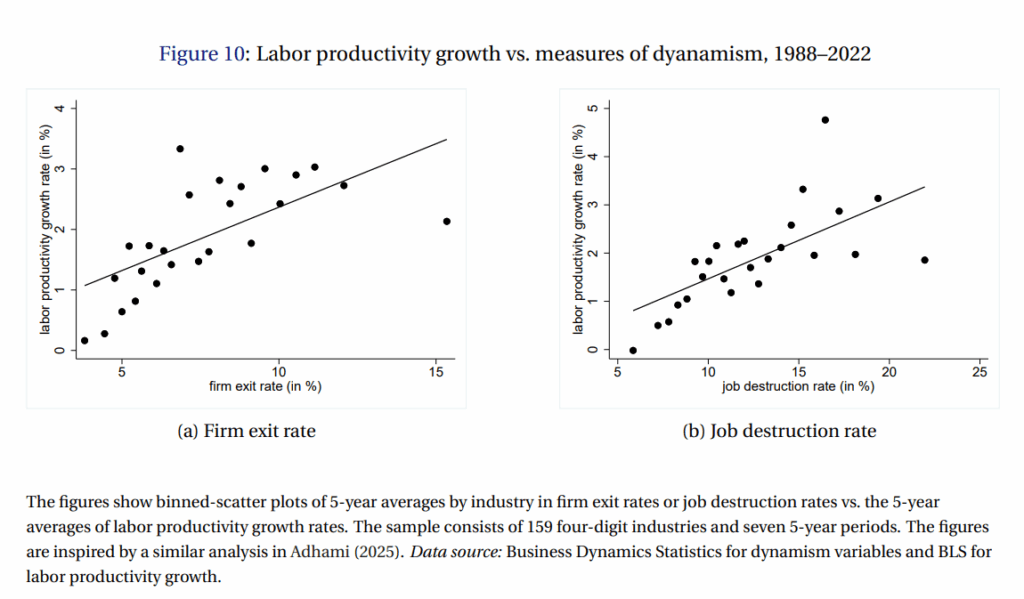

Creative Destruction in a Nutshell

A good figure from the Nobel Prize Foundation’s Scientific Background to the Mokyr, Aghion and Howitt Nobel. The figure shows that firm exit rates and job destruction rates are positively correlated with growth in labor productivity; creative destruction in a nutshell.

Rare Earths Aren’t Rare

Every decade or so there is a freakout out about China’s monopoly in rare earths. The last time was in 2010 when Paul Krugman wrote:

You really have to wonder why nobody raised an alarm while this was happening, if only on national security grounds. But policy makers simply stood by as the U.S. rare earth industry shut down….The result was a monopoly position exceeding the wildest dreams of Middle Eastern oil-fueled tyrants.

…the affair highlights the fecklessness of U.S. policy makers, who did nothing while an unreliable regime acquired a stranglehold on key materials.

A few years later I pointed out that the crisis was exaggerated:

- The Chinese government might or might not have wanted to take advantage of their temporary monopoly power but Chinese producers did a lot to evade export bans both legally and illegally.

- Firms that had been using rare earths when they were cheap decided they didn’t really need them when they were expensive.

- New suppliers came on line as prices rose.

- Innovations created substitutes and ways to get more from using less.

Well, we are at it again. Tim Worstall, a rare earths dealer and fine economist, is the one to read:

…rare earths are neither rare nor earths, and they are nearly everywhere. The biggest restriction on being able to process them is the light radioactivity the easiest ores (so easy they are a waste product of other industrial processes — monazite say) contain. If we had rational and sensible rules about light radioactivity — alas, we don’t — then that end of the process would already be done. Passing Marco Rubio’s Thorium Act would, for example, make Florida’s phosphate gypsum stacks available and they have more rare earths in them than several sticks could be shaken at.

Some also point out that only China has the ores with dysprosium and terbium — needed for the newly vital high temperature magnets. This is also one of those things that is not true. A decade back, yes, we did collectively think that was true. The ores — “ionic clays” — were specific to South China and Burma. Collective knowledge has changed and now we know that they can exist anywhere granite has weathered in subtropical climes. I have a list somewhere of a dozen Australian claimed deposits and there is at least one company actively mining such in Chile and Brazil.

…No, this is not an argument that we should have subsidised for 40 years to maintain production. It’s going to be vastly cheaper to build new now than it would have been to carry deadbeats for decades. Quite apart from anything else, we’re going to build our new stuff at the edge of the current technological envelope — not just shiny but modern.

As Tyler says, do not underrate the “elasticity of supply.”

Predicting Job Loss?

Hardly a day goes by without a new prediction of job growth or destruction from AI and other new technologies. Predicting job growth is a growing industry. But how good are these predictions? For 80 years the US Bureau of Labor Statistics has forecasted job growth by occupation in its Occupational Outlook series. The forecasts were generally quite sophisticated albeit often not quantitative.

In 1974, for example, the BLS said one downward force for truck drivers was that “[T]he trend to large shopping centers rather than many small stores will reduce the number of deliveries required.” In 1963, however, they weren’t quite so accurate about about pilots writing “Over the longer run, the rate of airline employment growth is likely to slow down because the introduction of a supersonic transport plane will enable the airlines to fly more traffic without corresponding expansion in the number of airline planes and workers…”. Sad!

In a new paper, Maxim Massenkoff collects all this data and makes it quantifiable with LLM assistance. What he finds is that the Occupational Outlook performed reasonably well, occupations that were forecast to grow strongly did grow significantly more than those forecast to grow slowly or decline. But was there alpha? A little but not much.

…these predictions were not that much better than a naive forecast based only on growth over the previous decade. One implication is that, in general, jobs go away slowly: over decades rather than years. Historically, job seekers have been able to get a good sense of the future growth of a job by looking at what’s been growing in the past.

If past predictions were only marginally better than simple extrapolations it’s hard to believe that future predictions will perform much better. At least, that is my prediction.

Democracy and Capitalism are Mutually Reinforcing

Many people argue that democracy is incompatible with capitalism but they differ on whether democracy will kill capitalism or whether capitalism will kill democracy. Peter Thiel, for example, famously said, “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible.” Thiel’s argument has a long-pedigree. The classical economists from Adam Smith to John Stuart Mill all worried that democracy would kill capitalism. Even Marx and Engels agreed with the analysis arguing that under democracy “The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralize all instruments of production in the hands of the State…” they differed only in welcoming such a revolution.

On the other side of the aisle we have the moderns such as Robert Reich and Joseph Stiglitz who argue in Reich’s words that Capitalism is Killing Democracy as “Corporations” and “billionaire capitalists have invested ever greater sums in lobbying, public relations, and even bribes and kickbacks, seeking laws that give them a competitive advantage over their rivals…”

A third argument, consistent with the views of Hayek, Mises, Friedman and others, is that capitalism and democracy are compatible and even mutually reinforcing. Ludwig von Mises, for example, argued that “Liberalism must necessarily demand democracy as its political corollary.”

My latest paper (WP version) (with Vincent Geloso) is in the new book, Can Democracy and Capitalism be Reconciled? We take the third view and show empirically that capitalism and democracy go hand in hand. We also provide some mechanisms for this correlation which I may discuss in a future post.

The data is very clear that democracy and capitalism go hand in hand. The figure below, for example, uses the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom Index to measure capitalism and the Varieties of Democracy Index to measure democracy (we use liberal democracy for convenience but show the correlations are strong with any variety of democracy).

Every major democracy is a capitalist country and virtually every capitalist country is a democracy (Singapore and Hong Kong being the only two exceptions.) Moreover, the upper left region–countries with a lot of democracy and low economic freedom, i.e. state control of the economy–what we might call the “Democratic Socialism” region–is empty.

We show further in the paper that changes in democracy are positively correlated with changes in economic freedom. We can see this very clearly by examining a natural experiment–the fall of the Berlin Wall. The fall of the Berlin Wall created a big positive shock to democracy which was followed by large and sustained increases in economic freedom.

It is sometimes argued that only an authoritarian regime is capable of “imposing” big increases in economic freedom and this is clearly false but it is true that there have been large increases in economic freedom in some authoritarian regimes. In the paper we look at the biggest such cases, Peru, Nicaragua, Uganda and Chile. The case of Peru carries some general lessons.

Peru began in 1970 with an authoritarian regime and only modest economic freedom. Economic freedom declined under an authoritarian regime and to levels well below those of any democracy. Modest increases in democracy brought modest increases in economic freedom. Under the authoritarian Fujimori regime there were large increases in economic freedom which in the 2000s were ratified, solidified and strengthened under democratic governments.

What we learn from this brief history is that authoritarian regimes can decrease as well as increase economic freedom. Indeed, one reason we sometimes see big increases in economic freedom under authoritarian regimes is simply that they are starting from the wreckage left by the previous regime. It’s easy to increase economic freedom a lot when you begin with a base level far below that of any democratic regime. Moreover, the Peru case is representative in that when a democratic regime is established it typically does not reject but instead ratifies and strengthens economic freedom.

What accounts for the correlation in economic freedom and democracy? The paper discusses a number of mechanisms of which I will only mention two here. Consider two ways to get rich, redistribution and growth. Redistribution can make a minority rich at the expense of a majority. A dictator can live in luxury amid national misery. But no redistribution scheme can enrich the majority—only growth can. Broad prosperity comes not from dividing wealth, but from creating it through pro-growth, capitalist policies. As a result, in a democracy, the rulers, the demos, can only get rich through growth and this provides some incentive to think about capitalism and economic freedom. The incentive is not a guarantee, of course, democratic voters can vote for bad policies but if they want to get rich they have to think about growth and that means capitalism.

The second reason for the correlation is a negative one, democratic socialism collapses into authoritarian socialism. As Robert Dahl argued:

It is not the inefficiencies of a centrally planned economy…that are most injurious to democratic prospects. It is the economy’s social and political consequences.

A centrally planned economy puts the resources of the entire economy at the disposal of government leaders. …“power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

A centrally planned economy issues an outright invitation to government leaders, written in bold letters: You are free to use all these economic resources to consolidate and maintain your power!

The bottom line is if you care about economic freedom, democracy is the way to go and if you care about democracy, economic freedom is the way to go.

Read the paper (WP version) for more.