Markets in Everything: Fentanyl Precursors

Reuters: To learn how this global industry works, reporters made multiple buys of precursors over the past year. Though a few of the sales proved to be scams, the journalists succeeded in buying 12 chemicals that could be used to make fentanyl, according to independent chemists consulted by Reuters. Most of the goods arrived as seamlessly as any other mail-order package. The team also procured secondary ingredients used to process the essential precursors, as well as basic equipment – giving it everything needed to produce fentanyl.

The core precursors Reuters bought would have yielded enough fentanyl powder to make at least 3 million tablets, with a potential street value of $3 million – a conservative estimate based on prices cited by U.S. law enforcement agencies in published reports over the past six months.

The total cost of the chemicals and equipment Reuters purchased, paid mainly in Bitcoin: $3,607.18.

I don’t doubt that Reuters did what they say they did. I have trouble believing, however, that the implied profit margins are so high. A gram of cocaine costs about $160 on the street and $13 to $70 trafficked into the US and ready to sell. Thus, the street price to production cost is at most 12:1 and perhaps as low as 2.3:1. Note that this profit margin includes the costs of jail etc. I think Reuters overestimates fentanyl street prices by a factor of 2 which would still give a ratio of 415:1 which is way too high. Let’s say fentanyl sells for $1.5 million on the street then to get the ratio to a very generous 20:1 we need costs of $75,000 so my guess is that Reuters has underestimated costs by a significant amount in some manner.

Happy to receive clarification or verification from those with more expertise in the business.

I do accept Reuters point that fentanyl is cheap and easy to produce.

The whole story is excellent.

Overturn Euclid v. Ambler

An excellent post from Maxwell Tabarrok at Maximum Progress:

On 75 percent or more of the residential land in most major American cities it is illegal to build anything other than a detached single-family home. 95.8 percent of total residential land area in California is zoned as single-family-only, which is 30 percent of all land in the state. Restrictive zoning regulations such as these probably lower GDP per capita in the US by 8–36%. That’s potentially tens of thousands of dollars per person.

The legal authority behind all of these zoning rules derives from a 1926 Supreme Court decision in Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co. Ambler realty held 68 acres of land in the town of Euclid, Ohio. The town, wanting to avoid influence, immigration, and industry from nearby Cleveland, passed a restrictive zoning ordinance which prevented Ambler realty from building anything but single family homes on much of their land, though they weren’t attempting to build anything at the time of the case.

Ambler realty and their lawyer (a prominent Georgist!) argued that since this zoning ordinance severely restricted the possible uses for their property and its value, forcing the ordinance upon them without compensation was unconstitutional.

The constitutionality claims in this case are about the 14th and 5th amendment. The 5th amendment to the United States Constitution states, among other things, that “private property [shall not] be taken for public use, without just compensation.” The part of the 14th amendment relevant to this case just applies the 5th to state and local governments.

The local judge in the case, who ruled in favor of Ambler (overturned by the Supreme Court), understood exactly what was going on:

The plain truth is that the true object of the ordinance in question is to place all the property in an undeveloped area of 16 square miles in a strait-jacket. The purpose to be accomplished is really to regulate the mode of living of persons who may hereafter inhabit it. In the last analysis, the result to be accomplished is to classify the population and segregate them according to their income or situation in life … Aside from contributing to these results and furthering such class tendencies, the ordinance has also an esthetic purpose; that is to say, to make this village develop into a city along lines now conceived by the village council to be attractive and beautiful.

Note that overturning Euclid v. Ambler would not make zoning in the interests of health and safety unconstitutional. Indeed, it wouldn’t make any zoning unconstitutional it would just mean that zoning above and beyond that required for health and safety would require compensation to property owners.

Read the whole thing and subscribe to Maximum Progress.

Cuba Libre! Part 2

In April I posted, following an excellent piece by Martin Gurri, that 4% of Cuba’s population had recently escaped. The Miami Herald now reports, based on official Cuban data, that 4% was a large underestimate.

A stunning 10% of Cuba’s population — more than a million people — left the island between 2022 and 2023, the head of the country’s national statistics office said during a National Assembly session Friday, the largest migration wave in Cuban history.

…It was a somber moment that capped a week of National Assembly sessions in which government officials shared data revealing the extent of the economic crisis and the failure of current government policies meant to increase production, address widespread shortages, deal with crumbling infrastructure and tame inflation.

Most seriously food production has collapsed:

Alexis Rodríguez Pérez, a senior official at the Ministry of Agriculture, said the country produced 15,200 tons of beef in the first six months of this year. As a comparison, Cuba produced 172,300 tons of beef in 2022, already down 40% from 289,100 in 1989.

Pork production fared even worse. The country produced barely 3,800 tons in the first six months of this year, compared to 149,000 tons in all of 2018. Almost every other sector reported losses and failed production goals.

And yet

…Cuban Prime Minister Manuel Marrero announced several new restrictions on the island’s private sector (!!!)

Raul Castro is 93. I am betting that his death or something similar will signal a new revolution. Is the US prepared for an open Cuba?

Not Lost In Translation: How Barbarian Books Laid the Foundation for Japan’s Industrial Revoluton

Japan’s growth miracle after World War II is well known but that was Japan’s second miracle. The first was perhaps even more miraculous. At the end of the 19th century, under the Meiji Restoration, Japan transformed itself almost overnight from a peasant economy to an industrial powerhouse.

After centuries of resisting economic and social change, Japan transformed from a relatively poor, predominantly agricultural economy specialized in the exports of unprocessed, primary products to an economy specialized in the export of manufactures in under fifteen years.

In a remarkable new paper, Juhász, Sakabe, and Weinstein show how the key to this transformation was a massive effort to translate and codify technical information in the Japanese language. This state-led initiative made cutting-edge industrial knowledge accessible to Japanese entrepreneurs and workers in a way that was unparalleled among non-Western countries at the time.

Here’s an amazing graph which tells much of the story. In both 1870 and 1910 most of the technical knowledge of the world is in French, English, Italian and German but look at what happens in Japan–basically no technical books in 1870 to on par with English in 1910. Moreover, no other country did this.

Translating a technical document today is much easier than in the past because the words already exist. Translating technical documents in the late 19th century, however, required the creation and standardization of entirely new words.

…the Institute of Barbarian Books (Bansho Torishirabesho)…was tasked with developing English-Japanese dictionaries to facilitate technical translations. This project was the first step in what would become a massive government effort to codify and absorb Western science. Linguists and lexicographers have written extensively on the difficulty of scientific translation, which explains why little codification of knowledge happened in languages other than English and its close cognates: French and German (c.f. Kokawa et al. 1994; Lippert 2001; Clark 2009). The linguistic problem was two-fold. First, no words existed in Japanese for canonical Industrial Revolution products such as the railroad, steam engine, or telegraph, and using phonetic representations of all untranslatable jargon in a technical book resulted in transliteration of the text, not translation. Second, translations needed to be standardized so that all translators would translate a given foreign word into the same Japanese one.

Solving these two problems became one of the Institute’s main objectives.

Here’s a graph showing the creation of new words in Japan by year. You can see the explosion in new words in the late 19th century. Note that this happened well after the Perry Mission. The words didn’t simply evolve, the authors argue new words were created as a form of industrial policy.

By the way, AstralCodexTen points us to an interesting biography of a translator at the time who works on economics books:

[Fukuzawa] makes great progress on a number of translations. Among them is the first Western economics book translated into Japanese. In the course of this work, he encounters difficulties with the concept of “competition.” He decides to coin a new Japanese word, kyoso, derived from the words for “race and fight.” His patron, a Confucian, is unimpressed with this translation. He suggests other renderings. Why not “love of the nation shown in connection with trade”? Or “open generosity from a merchant in times of national stress”? But Fukuzawa insists on kyoso, and now the word is the first result on Google Translate.

There is a lot more in this paper. In particular, showing how the translation of documents lead to productivity growth on an industry by industry basis and a demonstration of the importance of this mechanism for economic growth across the world.

The bottom line for me is this: What caused the industrial revolution is a perennial question–was it coal, freedom, literacy?–but this is the first paper which gives what I think is a truly compelling answer for one particular case. Japan’s rapid industrialization under the Meiji Restoration was driven by its unprecedented effort to translate, codify, and disseminate Western technical knowledge in the Japanese language.

Every Stock is a Vaccine Stock, Revisited

In May 2020, I wrote a post titled Every Stock is a Vaccine Stock highlighting that the stock market reaction to good vaccine news indicated that vaccines were worth trillions and that most of this value was external to the vaccine manufacturers, meaning that the vaccine manufacturers were under-incentivized.

It’s not surprising that when Moderna reports good vaccine results, Moderna does well. It’s more surprising that Boeing and GE not only do well they increase in value far more than Moderna. On May 18, for example, when Moderna announced very preliminary positive results on its vaccine it’s market capitalization rose by $5b. But GE’s market capitalization rose by $6.82 billion and Boeing increased in value by $8.73 billion.

A cure for COVID-19 would be worth trillions to the world but only billions to the creator. The stock market is illustrating the massive externalities created by innovation. Nordhaus estimated that only 2.2% of the value of innovation was captured by innovators. For vaccine manufacturers it’s probably closer to .2%.

Who can internalize the externalities? Moderna clearly can’t because if they could then on May 18 Moderna would have increased in value by $20.52b ($4.97b+$6.82b+$8.73b) and GE and Boeing wouldn’t have gone up at all. Massive externalities.

A clever institutional investor like Blackrock or Vanguard could internalize some of the externalities by encouraging Moderna to work even faster and invest even more, even to the extent of lowering Moderna’s profits. Blackrock would more than make up for the losses on Moderna by bigger gains on other firms in its portfolio. Blackrock does indeed understand the incentives, although its unclear how much beyond jawboning they can actually do, legally.

I’d like to see more innovation in mechanisms to internalize externalities–perhaps in a pandemic vaccine firms should be given stock options on the S&P 500. Until we develop those innovations, however, the government is the best bet at internalizing the externality by paying vaccine manufacturers to increase capacity and move more quickly than their own incentives would dictate. Billions in costs, trillions in benefits.

A new paper by Acharya, Johnson, Sundaresan and Zheng formulizes this intuition. The authors combine a model of preferences in which uncertainty can be priced with an estimate of the stock market reaction to vaccine news and conclude that “ending the pandemic would have been worth from 5% to 15% of total wealth”.

One measure of the ex ante cost of disasters is the welfare gain from shortening their expected duration. We introduce a stochastic clock into a standard disaster model that summarizes information about progress (positive or negative) toward disaster resolution. We show that the stock market response to duration news is essentially a sufficient statistic to identify the welfare gain to interventions that alter the state. Using information on clinical trial progress during 2020, we build contemporaneous forecasts of the time to vaccine deployment, which provide a measure of the anticipated length of the COVID-19 pandemic. The model can thus be calibrated from market reactions to vaccine news, which we estimate. The estimates imply that ending the pandemic would have been worth from 5% to 15% of total wealth as the expected duration varied in this period.

Disappearing polymorphs

Here’s a wild phenomena I wasn’t previously aware of: In crystallography and materials science, a polymorph is a solid material that can exist in more than one crystal structure while maintaining the same chemical composition. Diamond and graphite are two polymorphs of carbon. Diamond is carbon crystalized with an isometric structure and graphite is carbon crystalized with a hexagonal structure. Now imagine that one day your spouse’s diamond ring turns to graphite! That’s unlikely with carbon but it happens with other polymorphs when a metastable (locally) stable version becomes seeded with a stable version.

The drug ritonavir originally used for AIDS (and also a component of the COVID medication Paxlovid), for example, was created in 1996 but in 1998 it couldn’t be produced any longer. Despite the best efforts of the manufacturer, Abbott, every time they tried to create the old ritonavir a new crystalized version (form II) was produced which was not medically effective. The problem was that once form II exists it’s almost impossible to get rid of it and microscopic particles of form II ritonavir seeded any attempt to create form I.

Form II was of sufficiently lower energy that it became impossible to produce Form I in any laboratory where Form II was introduced, even indirectly. Scientists who had been exposed to Form II in the past seemingly contaminated entire manufacturing plants by their presence, probably because they carried over microscopic seed crystals of the new polymorph.

Wikipedia continues:

In the 1963 novel Cat’s Cradle, by Kurt Vonnegut, the narrator learns about Ice-nine, an alternative structure of water that is solid at room temperature and acts as a seed crystal upon contact with ordinary liquid water, causing that liquid water to instantly freeze and transform into more Ice-nine. Later in the book, a character frozen in Ice-nine falls into the sea. Instantly, all the water in the world’s seas, rivers, and groundwater transforms into solid Ice-nine, leading to a climactic doomsday scenario.

Given the last point you will perhaps not be surprised to learn that the hat tip goes to Eliezer Yudkowsky who worries about such things.

Emile Zola’s The Ladies’ Paradise Reviewed by Furman

Jason Furman (eight years as a top economic adviser to President Obama) is an excellent economist who reads a lot of books. His Goodreads has 2300 books read, with some 1200 reviews in economics, fiction, history and science. I greatly enjoyed his latest review of Zola’s The Ladies Paradise which came about after he “asked a colleague in the English department if any fiction had positive depictions of business and capitalism (other than Ayn Rand).” Here is Furman’s review:

A 19th century novel that is a paean to the consumer welfare standard.

…The department store is really the leading character in this book, the protagonist of the Bildungsroman. It is like a living, breathing creature with needs, desires and most importantly constant growth. It becomes increasing complex, mature and alive as it develops. From a few departments to many, takes over more and more of the square block—eventually engulfing the one stubborn holdout. The novel also has amazing depictions of innovations, not just classical invention (e.g., an improved type of umbrella at one point) but also management of inventory, holding sales, selling some products at a loss, advertising, managing inventories, and more. I never thought an entire chapter of a novel (and they’re long chapters) devoted to inventory management could be so thrilling but that one was nothing compared to the description of the sale.

In the shadow of the Ladies Paradise are a number of small shops that are having an increasingly difficult time competing. The larger shop buys out some, builds on innovations by others, and aggressively competes on price with still others. Émile Zola does not sugarcoat the pain of all of this, depicting deaths and suicide attempts in the wake of the store. But he does not blame all the maladies on the Ladies Paradise itself and, consistent with the consumer welfare standard, he keeps the focus on the ways in which this profit ultimately benefits customers. Moreover, some of the small businesses do innovate in ways that help keep themselves in business: “longing to create competition for the colossus; [a small business owner] believed that victory would be certain if several specialized shops where customers could find a very varied choice of goods could be created in the neighbourhood.”

Interestingly there is a chapter that reads like an explanation of an economic model, Bertrand competition, in which two competitors keep lowering prices by smaller and smaller amounts until they are pricing as low as they possibly can (their marginal cost). What made this especially interesting to me was that The Ladies Paradise was published in 1883, the same year Joseph Louis François Bertrand published his model.

And it is not just consumers. The novel depicts how the productivity gains the Ladies Paradise makes as a result of its scale and its innovations are passed through to workers in the form of higher pay and improved benefits. For example, early on there is a brutal depiction of the process of laying off workers during the slow time of year. Later on, the store develops a system that is more like furloughs with insurance. And also, unlike the small shops in the area, it has opportunities for advancement within the store, moving up the ranks of managerial positions. Notably, all of this is not because of the benevolence of the owner (as it is in a few other 19th century novels) but because of competition from other stores so the need to attract and retain talent.

All of this makes employment in the colossus considerably better than the smaller, neighboring shops where people are poorly paid, lack opportunities for advancement and face harassment. Although it is still not all wonderful—for example, the department store frowns on women who are married and dismisses them when they have children.

Overall, the combination of low prices for consumers and high expenses—including pay and benefits to attract and retain employees—mean that the business has a very thin profit margin but applies that margin to a very large base: “Doubtless with their heavy trade expenses and their system of low prices the net profit was at most four per cent. But a profit of sixteen hundred thousand francs was still a pretty good sum; one could be content with four per cent when one operated on such a scale.”

The biggest wrinkle in the consumer welfare standard is some of the ambivalence Zola has about consumer preferences themselves….The idea that people—or women to be more specific—are buying things they do not “need” but “desire” is an issue it grapples with. And that desire can even rise to the level of a mad frenzy, like the sales it depicts or the shoplifters, some of them affluent but driven by an almost mad desire to acquire lace, silk, and more.

All of this is embedded in a larger economic and technological system that is operating in the background: large factories in Lyon that are producing at scale in a way that is symbiotic with the department store, rail transportation to bring the constant inflow of goods, a mail system that supports catalog purchases, and more.

…I’m still astounded about how breathtaking fiction can be made which understands and depicts the ways in which innovation and scale combine with competition to generate benefits for consumers and workers—while also not sugarcoating the many that lose from this process.

Managing AI Employees

Lattice is a platform for managing employees. I believe this announcement from the Lattice CEO is real:

Today, Lattice made history: We became the first company to give digital workers official employee records in Lattice. This marks a huge moment in the evolution of A1 technology and of the workplace. It takes the idea of an “AI employee” from concept to reality — and marks the start of a new journey for Lattice, to lead organizations forward in the responsible hiring of digital workers. Within Lattice’s people platform, AI employees will be securely onboarded, trained, and assigned goals, performance metrics, appropriate systems access, and even a manager. We know this process will raise a lot of questions and we don’t yet have all the answers, but we want to help our customers find them. So we will be breaking ground, bending minds, and leaning into learning. And we want to bring everyone along on this journey with us.

On the one hand, this is wild. On the other hand, it makes perfect sense to use our current system of managing employees–performance reviews, training, feedback, yearly bonuses and so on–to manage AIs. In essence, human management systems become the interface for AI workers.

Every team will soon include AI workers. At first, this will be the AI stenographer who keeps the minutes, the admin who reminds everyone of their tasks, and the PowerPoint designer who puts together presentations but quickly this will evolve and some AIs will naturally take on supervisory roles until, my boss is an AI, will not seem strange.

Rent Control

Kholodilin offers a comprehensive review of the literature on rent control, some 206 papers, published and unpublished from 1967-2013. The results are summarized in the figure below where (-) indicates papers finding a negative effect, (0) no effect and (+) a positive effect. The top left figure, for example, shows, not surprisingly, that almost all papers find that rent controls does lower rents in the rent-controlled units.

Most papers that study the issue, however, find that rents increase in the uncontrolled units (middle row, right column.) In other words, “the imposition of rent control amplifies the shortage of housing. Therefore, the waiting queues become longer and would-be tenants must spend more time looking for a dwelling.”

Similarly, “nearly all studies indicate a negative effect of rent control on mobility” (top column, middle row).

Importantly, “the published studies are almost unanimous with respect to the impact of rent control on the quality of housing….[namely] that rent control leads to a deterioration in the quality of those dwellings subject to regulations.” (middle row, middle column).

Agricultural Productivity in Africa

If you look at total output, Peter Coy notes that sub-Saharan Africa looks quite impressive with gains in total output exceeding that in the rest of the world.

But almost all of this has come from using more inputs, especially land. If you look at output per unit of input, i.e. total factor productivity (TFP) then sub-Saharan Africa not only trails the rest of the world, it’s falling behind.

Things get much worse if you look at agricultural productivity by country. Alice Evans points us to “the most important graph” from work by Suri et al. (2024) which shows shockingly that since ~2010 agricultural productivity has plummeted in many African nations. I found this graph hard to believe.

Things get much worse if you look at agricultural productivity by country. Alice Evans points us to “the most important graph” from work by Suri et al. (2024) which shows shockingly that since ~2010 agricultural productivity has plummeted in many African nations. I found this graph hard to believe.

The numbers are correct based on data from the USDA but digging deeper, I noted that the two worst performing countries are Djibouti and Botswana–two small countries where agriculture is less than 5% of GDP and where climate and land mean that agriculture has no hope of ever being a great success. Moreover, Djibouti is growing rapidly and Botswana is a middle-income country with a booming economy. I suspect that what is going on here is that a growing economy is pulling the best (unmeasured) people and resources out of agriculture which leads what was already a small sector to become less productive on paper, albeit at no great loss to the economy.

In contrast, the countries where Ag TFP is rising the most are Zimbabwe and Senegal where agriculture is a much larger share of GDP and employment (Zimbabwe ~11-14% of GDP, 70% of employment and Senegal 16% of GDP, 30% of employment). So the good news is that agricultural productivity is growing in places where it is important.

Bottom line is that agricultural productivity in Africa is low. I see the primary cause as being small firms which means there are few opportunities for economies of scale, mechanization and R&D (see Suri et al. (2024) for a longer discussion.). Climate change is a threat and developing climate-resistant crops, especially for Africa where heat stress will become increasingly important, has high potential returns.

Overall, however, my conclusion is that although agricultural productivity in Africa is low and there are threats on the horizon the situation is getting modestly better rather than dramatically worse.

Time Preference, Parenthood and Policy Preferences

Using a small sample of couples before and after they have children, Alex Gazmararian finds that support for climate change policy increases after people have children. People also become more future-orientated when primed to think of children.

The short time horizons of citizens is a prominent explanation for why governments fail to tackle significant long-term public policy problems. Actual evidence of the influence of time horizons is mixed, complicated by the difficulty of determining how individuals’ attitudes would differ if they were more concerned about the future. I approach this challenge by leveraging a personal experience that leads people to place more value on the future: parenthood. Using a matched difference-in-differences design with panel data, I compare new parents with otherwise similar individuals and find that parenthood increases support for addressing climate change by 4.3 percentage points. Falsification tests and two survey experiments suggest that longer time horizons explain part of this shift in support. Not only are scholars right to emphasize the role of individual time horizons, but changing valuations of the future offer a new way to understand how policy preferences evolve.

It’s a little tricky to say that the driving force is time preference per se, maybe it’s just caring about (some) future people. Suppose a white man marries an African American woman. He subsequently may become more interested in civil rights, just as having children may make people more interested in the(ir) future. Or suppose that medical technology extends life expectancy, leading people to save more. Is this due to lower time preference or increased-self love?

We do see more parenthood driving future-oriented behavior on many margins. I am reminded, for example, of More Pregnancy, Less Crime which showed huge drops in criminal activity as people learn that they will be mothers and fathers. Criminals are very present-oriented so this effect is also consistent with parenthood driving lower time preference, although other stories are also possible. It’s difficult to distinguish these explanations and as far as policy and behavior is concerned perhaps the distinction between caring about the future and caring about future people doesn’t really matter.

How Many Workers Did It Take to Build the Great Pyramid of Giza?

The Great Pyramid of Giza was built circa 2600 BC and was the world’s tallest structure for nearly 4000 years. It consists of an estimated 2.3 million blocks with a weight on the order of 6-7 million tons. How many people did it take to construct the Great Pyramid? Vaclav Smil in Numbers Don’t Lie gives an interesting method of calculation:

The Great Pyramid’s potential energy (what is required to lift the mass above ground level) is about 2.4 trillion joules. Calculating this is fairly easy: it is simply the product of the acceleration due to gravity, the pyramid’s mass, and its center of mass (a quarter of its height)…I am assuming a mean of 2.6 tons per cubic meter and hence a total mass of about 6.75 million tons.

People are able to convert about 20 percent of food energy into useful work, and for hard-working men that amounts to about 440 kilojoules a day. Lifting the stones would thus require about 5.5 million labor days (2.4 trillion/44000), or about 275,000 days a year during [a] 20 year period, and about 900 people could deliver that by working 10 hours a day for 300 days a year. A similar number might be needed to emplace the stones in the rising structure and then smooth the cladding blocks…And in order to cut 2.6 million cubic meters of stone in 20 years, the project would have required about 1,500 quarrymen working 300 days per year and producing 0.25 cubic meters of stone per capita…the grand total would then be some 3,300 workers. Even if we were to double that in order to account for designers, organizers and overseers etc. etc….the total would be still fewer than 7,000 workers.

…During the time of the pyramid’s construction, the total population of Egypt was 1.5-1.6 million people, and hence the deployed force of less than 10,000 would not have amounted to any extraordinary imposition on the country’s economy.

I was surprised at the low number and pleased at the unusual method of calculation. Archeological evidence from the nearby worker’s village suggests 4,000-5,000 on site workers, not including the quarrymen, transporters and designers and support staff. Thus, Smil’s calculation looks very good.

What other unusual calculations do you know?

Doggerels for Deplorables

From Doggerels for Deplorables by D.M. Charette, with inspiration from Marginal Revolution.

Hope III: Assortative Mating

I hear how you proclaim the fault

for unequal shares in wealth

arises from the greediness

rich enjoy at poor’s expense.

But if you go through white papers [7,8]

you’ll notice one more factor

when you marry in your class

you increase the income gap.

Now let me call upon you all

who declare as liberal

to regard the bigger picture

when deciding on your future:

Seek outside of your career

ask out the single cashier

skip out on the grad event

hit the bar beside the plant

don’t inquire on film noir

learn to spot a muscle car

pass up on that back-stage tour

plant yourself in the bleachers.

So to decrease income division

you’ll marry someone not envisioned

but since you’re not a hypocrite

I’m certain you’ll be fine with it.

Addendum: Here is me on assortative mating in the economics profession and here is much more.

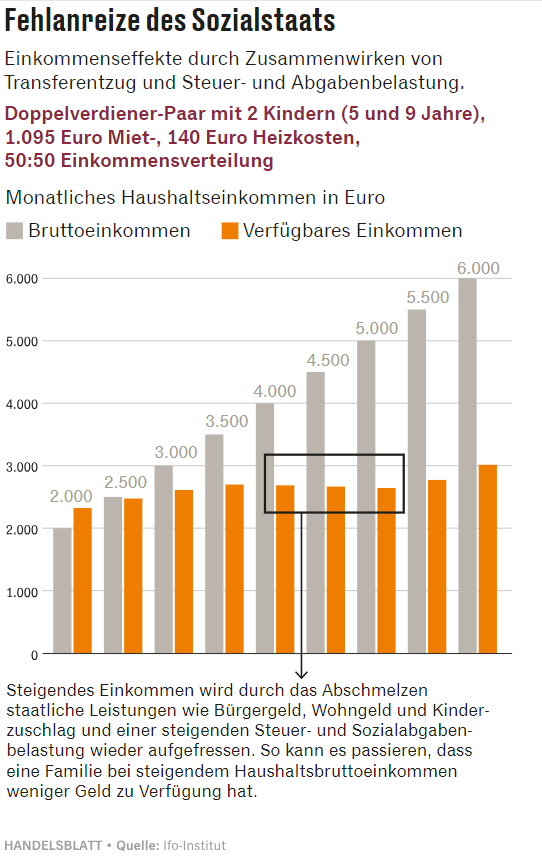

How the German welfare state punishes performance

The German welfare state is generous but this leads to implicit tax rates for those on welfare that can exceed 100%. Here’s a useful summary from the German newspaper Handelsblatt. (The original is in German, this is a Google translation.)

The German welfare state is generous but this leads to implicit tax rates for those on welfare that can exceed 100%. Here’s a useful summary from the German newspaper Handelsblatt. (The original is in German, this is a Google translation.)

Poorly coordinated state benefits such as the citizen’s allowance, housing benefit or child allowance often mean that additional work is not worthwhile or, in extreme cases, even leads to lower net income. The Ifo Institute has calculated this for various household types for the Handelsblatt newspaper – and shown how anti-performance the system sometimes is.

..A dual-income couple with two children aged five and nine, who work full-time and each earn 2000 euros gross per month, have a net income of 2686 euros with rent and heating costs of 1235 euros.

The couple therefore only has 887 euros more at their disposal per month than the household receiving citizen’s allowance. The absurd thing is that if the model working couple increases their joint income to 5,000 euros, the household’s net income falls by 43 euros to 2,643.

The graph shows that from a gross monthly income of 2000 Euro ($2150) (gray bars) to 6000 Euro ($6450) the net income gradient (orange bars) is nearly flat and in some regions it actually falls–meaning the couple would be better off by not working.

It’s hard to solve these problems. A negative income tax in which benefits would fall more slowly with income can restore incentives but at the price of having many more people on some welfare and a a much higher budgetary cost.

The Gary Becker Papers

The Gary Becker Papers (117.42 linear feet, 223 boxes) are now open at the University of Chicago:

The collection documents much of Gary Becker’s intellectual history. One of his autobiographical essays, “A Personal Statement About My Intellectual Development” (see Box 120, Folder 10 and Box 189, Folder 1), traces his academic career from his youth to his origins as a student at Princeton University, to his graduate student years and professorship at the University of Chicago, and his extra collegial engagement on corporate advisory boards, political participation, and governmental councils. The essay could have been written based on some of the records collected here. The collection documents an intellectual trajectory primarily through intellectual productions, research files, and communications. His approach to the research and writing, his publishing history, his engagement with others in the field of economics and other individuals in public service and global politics are contained here. Though the collection primarily concerns his professional life, there is also mention of his relationship with Guity Nashat, his wife, as they traveled together to the many conferences and events in the United States and abroad, and other incidents of his life for a minor study or treatment of his biography.

The collection materials include Becker’s handwritten and printed copies of his scholarship, including notes (and bibliographic cards), papers (and drafts), diagrams and charts, data sheets, correspondence, periodical reprints, magazines, newspapers and clippings, grant documents, reports, referee files, course and instructional materials, photographs, VHS tapes, DVD’s, and related ephemera.

Hat tip: Peter Istzin.