Category: Current Affairs

The ATM line inside the Greek parliament

The source is here. One television source is claiming 400 millions euros have been withdrawn from ATMs since the referendum was announced.

The Not Very Serious People call for Greferendum

Hugo Dixon has a good analysis:

My instant reaction to Alexis Tsipras’ decision to call a referendum on whether to accept creditors’ terms on Jul 5

1 Tsipras is effectively calling for Greece to quit the euro. Even if that’s not the question, that’s what it will amount to.

2 All sides have mishandled negotiation but Tsipras has mishandled it particularly badly.

3 Tsipras didn’t even complete the talks and wring out the last concessions. There was one more day to go.

4 Greece obviously won’t be able to pay the IMF on Tuesday.

5 Greece won’t be able to get extension of bailout which runs out on Tuesday, as referendum is following Sunday. Ie bailout expires.

6 ECB highly likely to stop emergency liquidity to banks. if capital controls not imposed on Monday, there will probably be bank run.

I would put it this way: when you call for a referendum in this kind of setting, you suffer all the costs of having to take a stance, and yet give up all of the potential benefits of control.

There are already reports of long lines at Greek ATMs. What’s the chance the Greferendum even ends up happening? As I’ve said before, the only thing worse than the Very Serious People are the Not Very Serious People.

Legal gay marriage

This is exciting and very positive news. Most of all, it is a breakthrough for those people who can now marry, or exercise the choice not to marry. There are two other aspects of the decision which I like. First, it keeps current the idea that the United States still is a world leader when it comes to liberty. Second, it encourages the idea that there are significant freedoms still to be won.

Which freedom will be next? Here is my earlier piece on Andrew Sullivan as the most influential public intellectual in recent times. Andrew even wrote a new post for the occasion.

Luddite Violence

Don’t make the mistake of thinking the Paris riots against Uber are worker versus capitalist, the attacks are rentiers versus capitalists and worker versus worker.

More pictures here.

King vs. Burwell, and other stuff

I have not been a fan of Obamacare, which I consider to be a highly inefficient form of wealth insurance. Nonetheless, had this decision gone the other way at this point we would have ended up with something worse, or ended back at “Obamacare as know it,” but only after a lot of political stupidity and also painful media coverage. So on net I take this to be good news, although arguably it is bad news that it is good news.

From the decision, insurers gained $3 billion in market value, and hospital stocks surged about ten percent, make of that what you will.

I found the remarks of Robert Laszlewski to be most to the point. Philip Wallach had some excellent legal and constitutional points, see also Cass Sunstein. I am very much a legal outsider, but it seems to me this does indeed rejigger something or other looking forward.

Elsewhere in the world, Schaueble does his best Scalia impression and tells us that June 30 is June 30, not July 1. Greece hasn’t exploded — yet — and everyone is wondering how much time is left on the shot clock. I’m still predicting an agreement, albeit one which will break pretty quickly.

TPP received fast track approval.

It’s been one of the best political weeks in years, although disconcertingly most of the good news has been avoiding even worse outcomes, not actual forward political progress of the kind one would like to be celebrating.

In Berlin, you can rent the smallest house in the world for one euro a night. And here is a baby owl, learning to fly, or so one would expect.

The continuing travails of Republican state-level fiscal policies

Lawmakers are stymied over how to pay for road and bridge repairs without raising taxes or fees, which Mr. [Scott] Walker has ruled out. The governor’s fellow Republicans rejected his proposal to borrow $1.3 billion for the roadwork, arguing that adding to the state’s debt is irresponsible.

In other words, Walker also has yet to come up with a state-level fiscal policy which consistently melds spending and taxing decisions; Trip Gabriel at NYT has more to say. As I argued earlier, these approaches to fiscal policy at the state level are not in every instance perfectly thought out. Just to be clear, this is not just a Republican vice: the Democrats have run the finances of states such as Illinois in a manner which is not entirely enviable.

Churches against Prohibition

The New England Conference of United Methodist Churches, a group of 600 churches, has issued a resolution calling for an end to the war on drugs. The resolution draws on ethical principles and also a remarkably astute reading of economics and social science:

Whereas: The public policy of prohibition of certain narcotics and psychoactive substances, sometimes called the “War on Drugs,” has failed to achieve the goal of eliminating, or even reducing, substance abuse and;

Whereas: There have been a large number of unintentional negative consequences as a result of this failed public policy and;

Whereas: One of those consequences is a huge and violent criminal enterprise that has sprung up surrounding the Underground Market dealing in these prohibited substances and;

Whereas: Many lives have been lost as a result of the violence surrounding this criminal enterprise, including innocent citizens and police officers and;

Whereas: Many more lives have been lost to overdose because there is no regulation of potency, purity or adulteration in the production of illicit drugs and;

Whereas: Our court system has been severely degraded due to the overload caused by prohibition cases and;

Whereas: Our prisons are overcrowded with persons, many of whom are non-violent, convicted of violation of the prohibition laws and;

Whereas: Many of our citizens now suffer from serious diseases, contracted through the use of unsanitary needles, which now threaten our population at large and;

Whereas: To people of color, the “War on Drugs” has arguably been the single most devastating, dysfunctional social policy since slavery and;

Whereas: Huge sums of our national treasury are wasted on this failed public policy and;

Whereas: Other countries, such as Portugal and Switzerland, have dramatically reduced the incidence of death, disease, crime, and addiction by utilizing means other than prohibition to address the problem of substance abuse and;

Whereas: The primary mission of our criminal justice system is to prevent violence to our citizens and their property, and to ensure their safety, therefore;

Be it Resolved: That the New England Annual Conference supports seeking means other than prohibition to address the problem of substance abuse; and is further resolved to support the mission of the international educational organization Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP) to reduce the multitude of unintended harmful consequences resulting from fighting the war on drugs and to lessen the incidence of death, disease, crime, and addiction by ending drug prohibition.

Greece fact of the day

What depresses us is how little attention has been paid to one major area of Greek government spending that seems ripe for the ax: defense spending. Greece spends a whopping 2.2% of GDP on defense, more than any NATO member-state save the United States and France. Bringing Greece into line with the NATO average would alone achieve ¾ of what the IMF is demanding through pension cuts.

There is more here from Benn Steil and Dinah Walker. And here is further discussion of the issue.

Tweets to ponder

Oddly, we probably owe the confederate flag removal to polarization. Could never get done when both sides competed for rural whites.

That is from @SeanTrende.

Is there a new Obamacare political equilibrium?

A Supreme Court ruling could gut an important facet of the Affordable Care Act as early as this week, but you wouldn’t know it from what the Republican presidential candidates have been talking about.

In the lead-up to the key 2012 Supreme Court ruling on health care reform – in which the justices decided the penalty paid by anyone without health coverage was a tax, and therefore constitutional – Republicans were abuzz about the possibility that the law could be overturned, and the issue featured prominently in campaign trail rhetoric.

But this time the GOP candidates for president have uttered barely a peep, even though the high court could decide the federal government cannot subsidize health insurance purchased through the federal exchange, which would leave millions of people without insurance and effectively unravel Obamacare as we know it.

That is from Rebecca Berg.

Harald Uhlig on Greece and fiscal austerity

“Fiscal austerity” is a clever label that somehow has stuck, but I think it is misleading. What has really been going on that Greece has been spending borrowed money, and they kept borrowing at a faster clip than what is sustainable. Suppose you do that as a household. What has to happen? At some point, you need to stop borrowing, you need to live within your means, and you have to either try to repay your debt or default. Everyone would like to spend more than what they receive! And, of course, it limits “growth” if you can no longer do that. But who is supposed to give you the resources for living beyond your means? What gets forgotten with the “fiscal austerity” label is this. Greece is free to borrow as much as they want on private markets, but private markets were no longer willing to lend to Greece. If Europe and the ECB had not stepped in and replaced much of that lost lending, if the debt terms would not have been renegotiated, it would have had a much more drastic effect on fiscal resources in Greece. So, one could argue (and I think it is fair to argue), that the European policies actually were the opposite of “fiscal austerity” compared to the benchmark case of only borrowing on private markets.

The full interview is here, via Garett Jones. And here is your Greece fact of the day:

The Greek banks might be able to survive [under Grexit] depending on what happens to their liabilities to the Eurosystem but it isn’t encouraging that more than half of their regulatory capital comes from deferred tax assets, which only have value if the banks are profitable and the Greek government has cash to pay.

That is Matthew C. Klein, from a longer post on the pros and cons of Grexit. And here is my earlier post Is Greece Really Going to Leave the Eurozone?, still a good guide.

Wage Effects of Transracialism

In today’s illustration of Cowen’s second law, here is a paper on what happens to wages when a worker’s subjectively reported race changes:

In Brazil, different employers often report different racial classifications for the same worker. We use this variation in employer-reported race to identify wage discrimination. Workers whose reported race changes from non-white to white receive a wage increase; those who change from white to non-white realize a symmetric wage decrease. As much as 40 percent of the raw racial wage gap is explained by the employer’s report of race, after controlling for all individual characteristics that do not change across jobs. The results are consistent with workers manipulating perceived race in an environment where racial classification is subjective, but discrimination persists.

Hat tip: Scott Cunningham.

The time needed to fill jobs

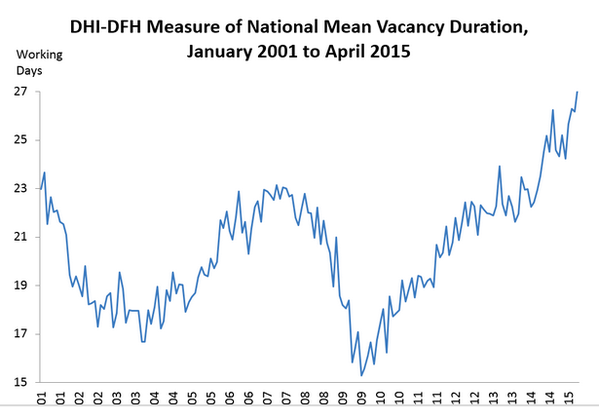

You can see a tightening labor market, and some of this you might interpret in terms of a growing skills gap:

The national time-to-fill average rose in February to the highest level in 15 years.

Sponsored by the career sites publisher Dice Holdings, the Dice-DFH Vacancy Duration Measure says it took an average of 26.8 working days to fill jobs in February. In January, according to the report, the average (as revised) was 25.7 working days.

“We are continuing to see signs of a tightening labor market,” said Michael Durney, president and CEO of Dice Holdings. “Unemployment rates are declining across several core industries, such as tech and healthcare, and the time-to-fill-open positions has hit an all-time high in the 15 years the data has been tracked.”

Jobs in the financial services sector took the longest to fill, averaging 43.1 days. Healthcare jobs averaged 42.6 days to fill. Both are historic highs for their respective industry sectors.

The full article, by John Zappe, is here, via David Wessel.

By the way, the skills mismatch hypothesis (not a substitute for AD hypotheses, let me stress) is stronger than you think. Catherine Rampell writes:

Companies themselves are indeed reporting difficulty acquiring talent. Nearly half of small and medium-size businesses with recent vacancies say they could find few or no “qualified applicants,” according to the latest monthly survey of the National Federation of Independent Business. Over the past couple of years, firms have also become increasingly likely to say that “quality of labor” is the “single most important problem” facing their businesses.

I have generally been skeptical of the “skills mismatch” story, mostly because wage growth has been so pitiful during this recovery. If qualified applicants were really so scarce, businesses should be bidding up the salaries of the few hot commodities available. But Steven J. Davis , an economics professor at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business and one of the creators of the vacancy duration metric, says it’s unclear how a widespread skills mismatch, if one exists, would actually affect wages. Maybe a shortage of some highly desirable skill would lead employers to bid up the price of that qualification, he says, but that same scarcity might also lead firms to instead settle “for workers who have less of [or] lower-quality versions of the desired skills.” That could, in theory, cause hourly wages to fall overall. Robust research on the connection between skills mismatch and wages is in short supply.

This point from Davis is appreciated only rarely.

China fact (?) of the day

According to the latest official data, profits earned by Chinese manufacturers rose 2.6% from a year earlier in April, a turnaround from a drop of 0.4% in the previous month. Yet nearly all of that increase—97%—came from securities investment income, data from the National Bureau of Statistics show. Excluding the investment income, China’s industrial profits were up 0.09%.

Meanwhile, over the course of 2014, the value of stocks, bonds and other tradable securities owned by listed Chinese companies rose by 946 billion yuan ($152.4 billion), a 60% increase, according to an analysis by Mr. Zhu.

The trend is starting to worry Chinese regulators, who have been trying to make sure that banks and the stock markets ultimately channel money into parts of the economy that create jobs.

There is some real wisdom in this passage:

“Manufacturing is a very hard business these days,” said Mr. Dong, chairman of the company. “I want to make some money from the stock market and use the profits to restart my manufacturing business later, when the economy turns for the better.”

That is from the WSJ, covered by FTAlphaville.

TPP

“If this [TPP] collapses, Pacific Rim countries will be aghast,” said Shunpei Takemori, a professor at Keio University in Japan, the largest economy in the would-be trade zone after the United States. “China is pushing, and if the U.S. just stands aside, it would be a tragedy.”

And:

“If you don’t do this deal, what are your levers of power?” Singapore’s foreign minister, K. Shanmugam, said in Washington on Monday. “The choice is a very stark one: Do you want to be part of the region, or do you want to be out of the region?”

He argued that “trade is strategy” and that without economic leverage, the United States was left with only military clout in Asia “and that’s not the lever you want to use.”

“It’s absolutely vital to get it done,” he added, referring to the bill’s passage.

The full article is here. I find the willingness of progressiveness to toss this bill into the wind, for the purposes of indulging the usual memes, to be one of the most depressing features of American political life in years.

You will find an alternative perspective from David Henderson here: “If the U.S. government is a “less reliable ally,” that could be a good thing.” I don’t think they feel that way in Singapore, South Korea, or Taiwan.

By the way, the fourth edition of Doug Irwin’s trade book is coming out.