Category: Current Affairs

Against an American sovereign wealth fund

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

It is true that the expected rate of return of the US stock market is higher than the US government’s borrowing rate. But what matters is the net social increase in investment value, not the nominal returns on the government’s portfolio. If the government buys some of my mutual funds, for instance, and it earns the 7% return that I would otherwise have earned, there is no net increase in social value. On paper, the sovereign wealth fund looks like a big success, but the government has simply issued more debt and redistributed some equity returns away from the citizenry and toward itself.

To the extent the government can initiate new investments and “pick winners,” it could boost overall social returns. But that is a far trickier endeavor than just putting funds into the stock market. And just as Democratic administrations have encouraged or mandated labor and diversity standards for many government subsidies and contracts, they might impose similar requirements on US SWFs — which would then be eliminated, or revised, under a Republican administration.

Recommended, there are other significant arguments at the link.

Honduras and its disputes

More importantly, Honduras is not just locked in a dispute with Silicon Valley billionaires, as the authors would lead you to believe. Other claimants against Honduras at the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) include the Paiz family, one of the wealthiest in Guatemala, the U.S. bank JPMorgan Chase, and others from Honduras, Panama, Mexico, Chile, Norway, and the Caymans. More claims were brought by private energy companies after Castro’s 2022 reforms pushed out private investment to expand the state’s role in electricity production. Predictably, there are no signs of progress for Honduras’ crippled energy grid. The state-run National Electric Energy Company loses over $30 million every month, with debts amounting to more than 10 percent of Honduran GDP.

This is to say that Honduras’ current feud with Próspera is part of a pattern of reneging on obligations to investors and expanding state influence, not a one-time rectification of a coup by Silicon Valley billionaires.

Equally absent the article is any mention that the supposedly “center-left” Castro is a self-proclaimed socialist strongly aligned with Venezuela and, in shirking foreign investors and the US, following in its footsteps quite neatly. Castro has indeed gone so far as to remove Honduras from the ICSID over the massive list of outstanding claims against it—a move familiar to Venezuela, which left in 2012. The Honduran government’s rationale—that the ICSID favors corporations instead of states—is the same that Venezuela used. The practical effects of this move are limited, but the symbolic ones are meaningful. Honduras is branding itself as a bad place to do business.

Here is more from Snowden Todd.

Elite Human Capital Is Not Just IQ

Here is a very good response to readers’ questions essay by Richard Hanania, excerpt:

Although EHC [elite human capital] types can make a lot of mistakes, it’s inevitable that they will rule and it’s mostly a good thing that they do. I think a society where most elites could stomach someone like Trump would have so much corruption that it would head towards collapse. This is why conservatives cannot build scientific institutions, and only a very small number of credible journalistic outlets. Right-wingers are discriminated against in academia and the media, but they mostly aren’t in these professions because they select out of them, since they lack intellectual curiosity and a concern for truth. If it doesn’t make them money or flatter their ego in a very simplistic way — in contrast to the more complicated and morally substantive ways in which liberals improve their own self-esteem — conservatives are not interested.

Conservatives complain about liberals “virtue signalling,” but one way to avoid that is to not care about virtue at all. And only by forsaking any ideals higher than “destroy the enemy” can a movement fall in line behind someone like Donald Trump. As already mentioned, I think that markets are counterintuitive to people, and Western civilization has done a good job of giving the entrepreneur his due. That said, EHC is a necessary part of any functioning civilization, and I see my job as helping to make it liberal rather than leftist. A truly conservative EHC class is something close to an oxymoron, since the first things smart people do when they begin to use reason are reject religion in public life and expand their moral circle.

The piece covers other issues as well.

Mental health trajectories in the UK

Yes, there is a human capital crisis of sorts:

We show the incidence of mental ill-health has been rising especially among the young in the years and especially so in Scotland. The incidence of mental ill-health among young men in particular, started rising in 2008 with the onset of the Great Recession and for young women around 2012. The age profile of mental ill-health shifts to the left, over time, such that the peak of depression shifts from mid-life, when people are in their late 40s and early 50s, around the time of the Great Recession, to one’s early to mid-20s in 2023. These trends are much more pronounced if one drops the large number of proxy respondents in the UK Labour Force Surveys, indicating fellow family members understate the poor mental health of respondents, especially if those respondents are young. We report consistent evidence from the Scottish Health Surveys and UK samples from Eurobarometer surveys. Our findings are consistent with those for the United States and suggest that, although smartphone technologies may be closely correlated with a decline in young people’s mental health, increases in mental ill-health in the UK from the late 1990s suggest other factors must also be at play.

That is from a new NBER working paper by David G. Blanchflower, Alex Bryson, and David N.F. Bell. By the way, on the “smart phone causality” issue, here are some recent musings. And a response, and a response to that.

Note that in my rough, first-order human capital hypothesis, the variance is rising. So the top achievers are considerably more impressive, but that also means the number of problematic cases, toward the bottom of the distribution, is rising as well.

Claims about Ireland (from the comments)

The proximate cause of this problem is the housing crisis, but the underlying reason is that Ireland’s political spectrum is still broken due to being defined by its reactions to colonialism and Catholicism. Beneath the surface-level tides of imperialism, rebellion, theocracy, and liberalisation is a deep nationwide conformism and lack of agency. There is a ‘learned helplessness’ from this illiberal past that conditions the population into modes of subservience and rebellion, with nothing in between.

Because the reactions against colonialism were both left-wing in character (republican and social liberalism) the entire population thinks of themselves as superficially left wing. The result is that each generation grows up with the same abstract ideas that problems are caused by “greed” and “corporations” but no conception of how oligarchy and government actually work to maintain an oppressive class system that is truly brutal compared even to much of western Europe.

The wealthy and influential networks in society use moral-sounding concepts such as environmental protection and invoking famine-era evictions to establish legal frameworks that protect existing capital by preventing growth. They also use the civil service as a massive programme of sinecures for the less ambitious within the upper middle classes. To take a random example: Ireland still claims to have ‘free’ university (though there is a significant registration fee). But the cost of renting is so high that effectively only the wealthy can send their kids away to college. Superficially left wing, but de facto oligarchy. This is everywhere: health service (half the population have private), public transport (unusable if you actually need to be somewhere), and there are shakedowns at every financial touchpoint — bank duopoly, huge insurance fees, dysfunctional legal system.

You’ll read a story in the news about how evil foreign investors are bulk buying homes and letting them out. What that actually means is that large capital-efficient reliable finance is outcompeting inefficient amateur Irish landlords, to the benefit of renters. The media will never report the story that way, because the ‘left wing’ story is best at protecting Ordinary Decent Irish Millionaires. None of the major parties will fight the civil service unions because the strongest voices in society get a lot of easy money through civil service jobs and contracts, and they will frame the debate as an attack on teachers and nurses.

The worst thing is that the people who are most oppressed by this (young people and poorer people) are most inclined to favour policies that have a superficially “left wing” appearance but just boil down to things like “greedy corporations are bad”, and have the effect of preventing growth and protecting existing asset ownership. James Joyce really captured this brilliantly — other writers describe the specific ailments, but Joyce saw the spiritual sickness of Irish society as it exists independent of particular forms of oppression. Fly by those nets.

That is from luzh.

The new Jerusalem Demsas book

On the Housing Crisis: Land, Development, Democracy. I just heard it is out today, of course I ordered my copy immediately…

Ireland fact of the day

Ireland ranks as the loneliest country in Europe, with almost a fifth of people lonely most or all of the time and nearly two-thirds of people suffer from anxiety or depression, according to EU data. One in seven children live in homes below the poverty line, defined as 60 per cent of the median disposable household income.

Here is more from the FT, with much of the piece about how Ireland should spend its budget surplus.

Taxing Unrealized Capital Gains and Interest Rate Policy

First read Tyler on the practical difficulties implementing a tax on unrealized capital gains!

I have a different argument that I rarely see discussed. A significant fraction of what we call capital gains is due to variation in the discount rate rather than variation in income. Take the simplest Gordon model of stocks P=D/r where D is the annual dividend and r is the discount rate. If D=100 and r=.1, for example, then the stock is worth 100/.1=$1000. Now suppose people become more patient and the discount rate falls to .05 then P=$100/.05=$2000. The stock price doubles, a massive capital gain. But notice that income hasn’t gone up at all. It’s still D per year. Income hasn’t gone up and lifetime consumption possibilities haven’t gone up for someone who doesn’t sell (but recall this is a tax on unrealized gains. If there is a sale then tax the realized gain.) Ultimately, we want to tax consumption so we should not be taxing “capital gains” which reflect changes in discount rates rather than changes in income or consumption possibilities.

Taxing unrealized capital gains also connects interest rate policy even more tightly with fiscal policy. Need a tax boost? Lower interest rates! Fed policy already influences taxes but this adds another lever for political business cycles. More generally, interest rate volatility now adds to fiscal volatility. When we exited zero interest rate policy, for example, banks had huge capital losses. As rates fall, capital gains increase. Do we really want to add the tax system to this?

If we generalize the Gordon model to P=D/(r-g) where g is the growth rate of dividends then we can see that another cause of increased capital gains, an increase in g. It’s not obvious that we should tax unrealized changes in asset values due to increases in the growth rate of dividends. On the one hand, this is more income-like but it’s expectational. It’s taxing the chickens before the eggs have hatched.

The one clear increase in income which should be taxed is increases in D. An unrealized capital gains tax would do that but at the expense of also taxing changes in asset values due to changes in r and g which should not be taxed.

Now add the point I mentioned to Tyler, which is that taxing unrealized gains divorces the entrepreneur from the firm at a time when the “marriage” is likely at its most productive. Not good. Taxing unrealized gains might not even be a good idea from the point of view of the tax collector. Does the IRS want to tax X now or a much larger figure later? If the IRS taxes entrepreneurship too early it can reduce total discounted tax revenues.

Bottom line: I don’t see how taxing unrealized capital gains is a well thought out policy. Eliminate the stepped up basis, declare victory and go home.

Addendum: Aguiar, Moll, and Scheuer make some similar points but embedded in a fully GE framework. Ben Moll also points me to earlier pieces by Frank Paish 1940, Nicholas Kaldor 1955 and John Whalley 1979.

Those new Japanese service sector job quitters, division of cease labor edition

“I didn’t want my ex-employer to deny my resignation and keep me working for longer,” she told CNN during a recent interview.

But she found a way to end the impasse. She turned to Momuri, a resignation agency that helps timid employees leave their intimidating bosses.

For the price of a fancy dinner, many Japanese workers hire these proxy firms to help them resign stress-free.

The industry existed before Covid. But its popularity grew after the pandemic, after years of working from home pushed even some of Japan’s most loyal workers to reflect upon their careers, according to human resources experts.

There is no official count on the number of resignation agencies that have sprung up across the country, but those running them can testify to the surge in demand…

“We sometimes get calls from people crying, asking us if they can quit their job based on XYZ. We tell them that it is okay, and that quitting their job is a labor right,” Kawamata added.

Some workers complain that bosses harass them if they try to resign, she said, including stopping by their apartments to ring their doorbell repeatedly, refusing to leave.

Here is the full story, via Michael Rosenwald.

Mpox Vaccines Stuck in Limbo: WHO is at Fault

In 2022, Mpox, a viral disease endemic to parts of Africa and primarily transmitted through close contact—especially sexual contact between men—spread to developed countries, including the United States. The U.S. saw over 30,000 cases and approximately 58 deaths. Despite two available vaccines there was not nearly enough supply to vaccinate even the high-risk populations. Fortunately, health authorities adopted vaccination strategies my colleagues and I had recommended for COVID such as first doses first and fractional dosing. For example, several small studies (e.g. here and here) suggested that 1/5 doses delivered intradermally could be effective and the FDA, EMA, and the UK all recommended this fractional dosing strategy. As result, the US was able to vaccinate around 800,000 people and the epidemic ended (natural immunity and other preventive measures also played a role).

Unfortunately, a new Mpox variant is now spreading in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and nearby countries. Here’s the crazy part: despite declaring Mpox a public health emergency on August 14, the WHO has not approved any Mpox vaccines. You might think, “Who cares what the WHO authorizes?” After all, the FDA, EMA, and the UK have all granted emergency approval. But here’s the catch: the WHO’s approval is crucial for GAVI, the vaccine alliance that donates vaccines to developing countries. Without WHO approval, GAVI is reluctant to provide vaccines to the Congo. To add insult to injury, the Congo itself has approved the Jynneos and LC16 vaccines. Yet, the WHO refuses to authorize and GAVI to donate these vaccines, citing vague concerns about safety and efficacy.

Stephanie Nolen at the NYTimes has a very good piece on this mess:

Three years after the last worldwide mpox outbreak, the W.H.O. still has neither officially approved the vaccines — although the United States and Europe have — nor has it issued an emergency use license that would speed access.

One of these two approvals is necessary for UNICEF and Gavi, the organization that helps facilitate immunizations in developing nations, to buy and distribute mpox vaccines in low-income countries like Congo.

While high-income nations rely on their own drug regulators, such as the Food and Drug Administration in the United States, many low- and middle-income countries depend on the W.H.O. to judge what vaccines and treatments are safe and effective, a process called prequalification.

But the organization is painfully risk-averse, concerned with a need to protect its trustworthiness and ill-prepared to act swiftly in emergencies, said Blair Hanewall…

In addition, no one has followed the other practice my colleagues and I recommended for COVID (which Operation Warp Speed did), namely advance market commitments. So the vaccine manufacturers have basically been twiddling their thumbs and not gearing up for greater production. (The Congo can also be faulted for not buying more on their own account.)

All of this means that when the WHO does authorize and the vaccines begin to flow, we will still desperately need strategies like fractional dosing.

Hat tip: Ben H. and special thanks to Witold Wiecek.

John Arnold on economic polarization

As divisive as the political rhetoric is, the policy divide between the two parties seems more narrow today than any time in recent memory. Bipartisan bills in immigration, energy permitting, and the child tax credit have been negotiated and waiting for political window to reopen. Foreign aid and military spending bills both passed in past year with strong bipartisan support. Same with infrastructure bill in 2021 and CHIPS Act in 2022. Both parties are anti-China, favorable to India, and increasingly supportive of industrial policy and tariffs. Both talk about lowering the cost of housing, more funding for the police, and are leery of big tech. Neither party is proposing big changes in health care, K-12 or social security. College loan forgiveness is in the courts. Abortion is now in the states. GOP opposition to the IRA climate provisions are around the edges, like EV subsidies. Dems aren’t proposing any new significant climate policies. Dems have enacted minor policies against oil and gas but production continues to reach record highs. Both say no new taxes for <$400k. Increasing number of Rs have joined Ds supporting increase in corp tax rates. Perhaps the biggest difference is how to pay for TCJA extension: Dems want higher taxes on the wealthy; Trump wants universal tariffs; the rest of GOP hasn’t been specific. There are other differences for sure. Dems want more subsidies for housing and child care. GOP wants more deportations (though logistically difficult). Dems would be more aggressive against consolidation, health care costs, and junk fees. GOP wants to restucture civil service rules. But there just aren’t many major fault lines on policy between the parties today. Maybe this is why so little of this election cycle is about policy.

Here is the full tweet. I would add that “ten percent tariffs” vs. “25% tax on unrealized capital gains” is a big difference, but at least one of those is never going to happen, even if the Republicans do not capture the Senate.

Why massive deregulation is very difficult

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, just to clarify context for the newbies I think more than half of all current regulations are a net negative. Anywhere, here are some of the problems:

Consider the relatively straightforward idea, popular in some Republican circles, of firing large numbers of federal bureaucrats. There would be immediate objections, not only from the employees themselves but also from US businesses.

Businesses need to make plans, and they frequently consult with regulatory agencies as to what might be permissible. The Food and Drug Administration needs to approve new drug offerings. The Federal Aviation Administration needs to approve new airline routes. The Federal Communications Commission needs to approve new versions of mobile phones. The Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice need to give green lights for significant mergers. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. needs to approve plans for winding down failed banks. And so on.

If those and other agencies were stripped of their staffs, a lot of US businesses would be paralyzed. You might argue that this fact is itself proof that there is too much regulation, but the fact remains. Shutting down a large chunk of the federal regulatory apparatus would make it harder, not easier, for the private sector. Furthermore, regulation would give way to litigation, and the judiciary is not obviously more efficient than the bureaucracy.

And this:

The basic paradox is this: Government regulations are embedded in a large, unwieldy and complex set of institutions. Dismantling it, or paring it back significantly, would require a lot of state capacity — that is, state competence. Yet deregulators are suspicious of greater state capacity, as it carries the potential for more state regulatory action. Think of it this way: If someone told a libertarian-leaning government efficiency expert that, in order to pare back the state, it first must be granted more power, he would probably run away screaming.

Recommended, the piece has numerous good points of interest.

Obama’s space legacy?

Bucking his central planning instincts, Obama embraced a surprisingly laissez-faire approach to space flight that angered political allies and opponents alike.

In doing so, however, he tapped a reservoir of ingenuity and innovation that has ushered in a new age of space flight and exploration…

In her forthcoming book Bureaucrats and Billionaires, former NASA deputy administrator Lori Garver and reporter Michael Sheetz trace the origins of NASA’s commercial crew program, a revolutionary human spaceflight program that joins private aerospace manufacturers such SpaceX and Boeing with NASA’s astronauts.

Garver writes that this hybrid allows space flight “at a fraction of the cost of previous government owned and operated systems.” A decade ago, however, the program faced opposition seemingly from every side.

The saga began early in 2010 when President Obama announced his intention to abort NASA’s Constellation program—NASA’s crew spaceflight program—correctly pointing out it was “over budget, behind schedule, and lacking in innovation.”

The decision angered almost everyone. As Garver and Sheetz write, the program was “extremely popular with Congress, and the contractors who were benefiting from the tax dollars coming their way.” An impressive array of stakeholders from aerospace companies, trade associations, and astronauts to lobbyists, Congressional delegations, and NASA pushed back.

The resistance was immense.

NASA chief Charles Bolden, while choking back tears, compared the decision to “a death in the family.” Pulitzer Prize winning columnist Charles Krauthammer ominously noted the move would give the Russians “a monopoly on rides into space.” Congressman Pete Olson (R-Texas) called the decision “a crippling blow to America’s human spaceflight program.”

Few commentators seemed to even notice the $6 billion in spending over five years to support commercially built spacecraft to launch NASA’s astronauts into outer space…

By pulling the plug on Constellation, Obama had unleashed the power of markets and competition. While many associate competition with dog-eat-dog and survival of the fittest tropes, competition is a healthy and productive force.

Here is the full story, by John Miltimore at FEE (!). Via Matt Yglesias.

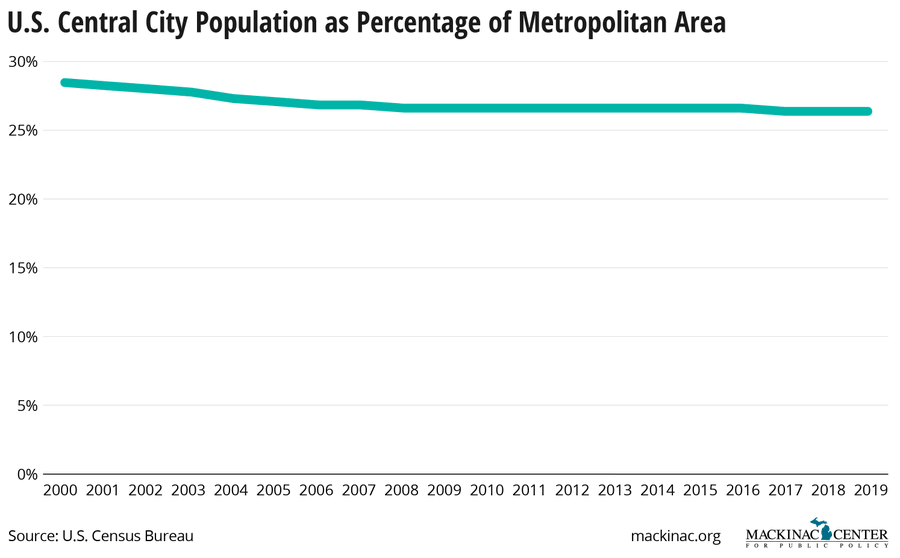

U.S: central city population as a % of metropolitan area

Via James Hohman.

What should I ask Musa al-Gharbi?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with him.

Musa al-Gharbi is a sociologist and assistant professor in the School of Communication and Journalism at Stony Brook University. He is a columnist for The Guardian and his writing has also appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and The Atlantic, among other publications.

I am a big fan of his forthcoming book We Have Never Been Woke, which I have blurbed. Here is Musa’s home page, do read his bio. Here is Musa on Twitter.

So what should I ask?