Category: Economics

Buffett’s Alpha

Berkshire Hathaway has realized a Sharpe ratio of 0.76, higher than any other stock or mutual fund with a history of more than 30 years, and Berkshire has a significant alpha to traditional risk factors. However, we find that the alpha becomes insignificant when controlling for exposures to Betting-Against-Beta and Quality-Minus-Junk factors. Further, we estimate that Buffett’s leverage is about 1.6-to-1 on average. Buffett’s returns appear to be neither luck nor magic, but, rather, reward for the use of leverage combined with a focus on cheap, safe, quality stocks. Decomposing Berkshires’ portfolio into ownership in publicly traded stocks versus wholly-owned private companies, we find that the former performs the best, suggesting that Buffett’s returns are more due to stock selection than to his effect on management. These results have broad implications for market efficiency and the implementability of academic factors.

Here is the paper by Andrea Frazzini, David Kabiller, and Lasse Heje Pedersen. Quite the run, now over. Via J.

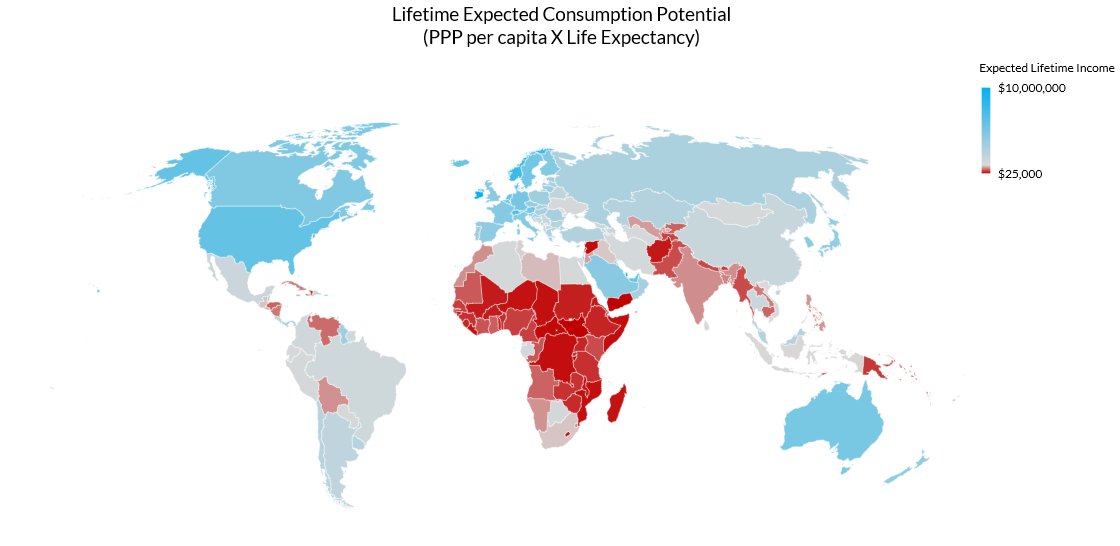

Lifetime Expected Consumption

What does it mean to be wealthy and how should we factor in say, life expectancy? Lyman Stone offers an interesting measure, lifetime consumption, taking in account (roughly) both years lived and how much one consumes in those years.

Tabarrok on the Not My Generation Podcast

Political Scientists James Davenport and Craig Dawkins interview me on everything from tariffs to the Borda Count. Here is one bit I wish to underline:

Q. In your opinion, what is the biggest economic myth or misconception that is holding the U.S. back?

What worries me most is that we’re treating China like an enemy—and that mindset risks becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. What I want people to understand is this: we have a lot to gain from a rich China.

In my 2009 TED Talk, I gave one of my favorite examples. As China grows wealthier, it invests more in thinking—research, science, and development—that benefits the entire world. Richer countries face diseases of aging, not poverty. As China shifts its focus to diseases like cancer, it ramps up investment in drug development. That raises the odds of a cure—something worth trillions to humanity. If an American cured cancer, I’d be thrilled. If a Chinese citizen cured cancer, I’d be 99.9% as thrilled.

Yes, China is not a democracy. But by global standards, it hasn’t been especially militaristic. There have been border disputes, but no major invasions in over 50 years. China isn’t sending troops to the Middle East or Latin America.

That could change. But nothing inescapable says the U.S. and China must be enemies. We have far more to gain from peace, trade, and prosperity than from conflict.

My Conversation with the excellent Ken Rogoff

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Ken and Tyler tackle international economic dynamics, unresolved macro puzzles, the state of chess, and more, including whether trade deficits are truly unsustainable, why China’s investment-heavy growth model has reached its limits, how currency depreciation neutralizes tariff effects, Pakistan’s IMF bailouts, whether more Latin American countries should dollarize, Japan’s deceptively peaceful economic decline, Europe’s coming fiscal reckoning, how the US will eventually confront its ballooning debt, the puzzling absence of a recession during our recent disinflation, the potential of phasing out large denomination currency notes, the future relevance of stablecoins, whether America should start a CBDC, Argentina’s chances under Milei, who will be the next dominant player in chess, hanging out with Bobby Fischer, drawing out against Magnus Carlsen, and how to save classical chess from excessive computer preparation.

Here is an excerpt:

COWEN: Just predictively, what do you think the United States will do with its fiscal position?

ROGOFF: That is a darn good question. Looking way forward, I would just say we’re on an unsustainable path. We will continue to have our debt balloon. Eventually — not necessarily in a planned or coherent way — I think we’re going to have another big inflation soon, next five to seven years, maybe sooner with what’s going on, and that’s going to bring it down just like it did under Biden. It brought the debt down. Then the markets are, fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, no, we’re raising the interest rate, and then we’ll have to make choices.

I think in the United States, a lot of the choices, I’m sorry to say, probably point towards higher taxation because we’re hardly running a welfare state. All due respects — and I’m not sure I have any due respects to DOGE — there’re not that many things to cut in the United States compared to many other countries. I don’t know what the choice will be. I probably won’t be here, and you might not be either, when we’re making the choices, but if actually we’ll —

COWEN: Oh, I think we’ll both be here.

ROGOFF: It could happen much sooner. On the other hand, it’s hard to know what’s going through Trump’s head. I presumed he was going to blow up the deficit, like everybody else. We’ll see.

COWEN: When you say big inflation, how big is big?

ROGOFF: Last time we probably had a bonus 10 percent inflation over the 2 percent target cumulatively, maybe 12 percent. I think this time, it’ll be more on the order of cumulatively over the 2 percent target, 20 percent, 25 percent. There’s going to be an adjustment. I don’t think the debt is going to be the sole contribution to that. There are many factors. You have to impinge on Federal Reserve independence. Probably, there’ll be some shock, which will justify it. I don’t know how it’s going to play out.

I know that for years, people have said the US debt is unsustainable, but it hasn’t come to roost because we’ve lived through this post-financial crisis, post-pandemic era of very, very low and negative real interest rates. That is not the norm. There’s regression to mean.

You know what? It’s happened. Suddenly, the interest payments start piling up. I think they’ve at least doubled over the last few years. They’re quickly on their way to tripling, of going up to $1 trillion. Suddenly, it’s more than our defense spending. That’s the most important macro change in the world, that real interest rates appear to have regressed more towards long-term trend.

COWEN: What’s the most plausible scenario you can imagine where the US does not have to make any major adjustment? I’m not saying you’re predicting it. I’m not saying you think it’s very plausible, but you have to come up with something. What is it?

Recommended. And I am happy to also recommend Ken’s new book Our Dollar, Your Problem: An Insider’s View of Seven Turbulent Decades of Global Finance, and the Road Ahead.

What Should Classical Liberals Do?

My little contretemps with Chris Rufo raises the issue of what should classical liberals do? In a powerful essay, C. Bradley Thompson explains why the issue must be faced:

The truth of the matter is that the Conservative-Libertarian-Classical Liberal Establishment gave away and lost an entire generation of young people because they refused to defend them or to take up the issues that mattered most to them, and in doing so the Establishment lost America’s young people to the rising Reactionary or Dissident Right, by which I primarily mean groups such as the so-called TradCaths or Catholic Integralists and the followers of the Bronze Age Pervert. (See my essay on the reactionary Right, “The Pajama-Boy Nietzscheans.”)

I do not think Mr. Rufo would disagree with me on this point, but he has not quite made it himself either (at least not as far as I know), so I will make it in my own name.

The betrayal, abandonment, desertion, and loss of America’s young people by conservative and libertarian Establishmentarians can be understood with the following hypothetical.

Imagine the plight of, let us say, a 23-year-old young man in the year 2016. Imagine that he’s been told every single day from kindergarten through the end of college that he’s racist, sexist, and homophobic by virtue of being white, male, and heterosexual. Further imagine that he was falsely diagnosed by his teachers in grade school with ADD/ADHD and put on Ritalin because, well, he’s an active boy. And then his teachers tell him when he’s 12 that he might not actually be a boy, but rather that he might be a girl trapped in boy’s body. And let us also not forget that he’s also been told by his teachers and professors that the country his parents taught him to love was actually founded in sin and is therefore evil. To top it all off: he didn’t get into the college and then the law school of his choice despite having test scores well above those who did.

In other words, what this oppressed and depressed young man has experienced his whole life is a cultural Zeitgeist defined by postmodern nihilism and egalitarianism. These are the forces that are ruining his life and making him miserable.

Let’s also assume that said young man is also temperamentally some kind of conservative, libertarian, or classical liberal, and he interns at the Heritage Foundation, the Cato Institute, or the Institute for Humane Studies hoping to find solace, allies, and support to give relief to his existential maladies.

And how does Conservatism-Libertarianism Inc. respond to what are clearly the dominant cultural issues of our time?

Well, the Establishment publishes yet another white paper on free-market transportation or energy policy. The Heritage Foundation doubles down on more white papers on deficits and taxation policy. The Cato Institute churns out more white papers on legalizing pot and same-sex marriage. The Institute for Humane Studies goes all in to sit at the cool kids’ lunch table by ramping up its videos on spontaneous order featuring transgender 20-somethings.

Is it any wonder that today’s young people who have suffered the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune are stepping outside the arc of history yelling, “stop”? At a certain point, these young people let out a collective primal scream, shouting “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore.” And when the “youf” (as they refer to themselves online) realized that Establishment conservatives and libertarians did not hear them and lacked the vocabulary, principles, power, and courage to defend them from their Maoist persecutors, they went underground to places like 4chan, 8chan, and various other online discussion boards, where they found a Samizdat community of the oppressed.

Having effectively abandoned late-stage Millennials and Gen Z, Conservatism and Libertarianism Inc. should not be surprised, then, that today’s young people who might be otherwise sympathetic to their policies have left that world and become radicalized. News flash: Gen Z is attracted to people who are willing to defend them and attack social nihilism and egalitarianism in all their forms.

Hence the rise of what I call the “Fight Club Right,” which calls for a new kind of American politics. Gen Z rightism is done with what they call the Boomer’s “fake and ghey” attachment to the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the institutions of the Constitution. In fact, many young people who have migrated to the reactionary Right have openly and repeatedly rejected the principles of the American founding as irrelevant in the modern world.

More to the point, this younger generation is done with the philosophy of losing. They’re certainly done with the Establishment. They also seem to be done with classical liberalism and the American founding. (This is a more complicated topic.) Instead, what they want is political power to punish their enemies and to take over the “regime.” They want to use the coercive force of the State to create their new America.

…Conservatism and Libertarianism Inc. seemed utterly oblivious to the fact that the Left had pivoted and changed tactics after the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. By the 1990s, the Left had abandoned economic issues and the working class and was doubling down on cultural issues. Rather than trying to take over the trade-union movement, for instance, the postmodern Left went for MTV and the Boy Scouts, while the major DC think tanks on the Right went for issues too distant from the lives of young people such as the deficit, taxation, and regulatory policy.

While socialism continues to be the end of the Left, the means to the end is postmodern nihilism. That’s where the Left planted its flag and that’s the terrain that it has occupied without opposition, whereas conservative and libertarian organizations such as the Heritage Foundation and the Cato Institute were fighting for ideological hegemony in the economic realm. Between 2000 and 2025, cultural nihilism and its many forms and manifestations is where the action is and has been for a quarter century. So powerful has postmodern nihilism become that even some left-wing “libertarian” organizations have simply become left-wing.

The Political Economy of Protective Labor Laws for Women

From a new NBER working paper:

During the first half of the twentieth century, many US states enacted laws restricting women’s labor market opportunities, including maximum hours restrictions, minimum wage laws, and night-shift bans. The era of so-called protective labor laws came to an end in the 1960s as a result of civil rights reforms. In this paper, we investigate the political economy behind the rise and fall of these laws. We argue that the main driver behind protective labor laws was men’s desire to shield themselves from labor market competition. We spell out the mechanism through a politico-economic model in which singles and couples work in different sectors and vote on protective legislation. Restrictions are supported by single men and couples with male sole earners who compete with women for jobs. We show that the theory’s predictions for when protective legislation will be introduced are well supported by US state-level evidence.

That is by Matthias Doepke, Hanno Foerster, Anne Hannusch, and Michèle Tertilt.

The Public Choice Outreach Conference

There are just a few spots left for the Public Choice Outreach Conference! Do encourage your students to apply!

Yale Faculty v. Administrators

Yale has approximately one administrator for every undergraduate student (see also here and here). Years of simmering tension about the growth of administration relative to faculty has now been brought forward. President Trump has threatened to cut funding to Yale, the Yale administration has threatened to stop hiring faculty and raises, some faculty are now threatening to revolt.

Over 100 Yale professors are calling for the University administration to freeze new administrative hires and commission an independent faculty-led audit to ensure that the University prioritizes academics.

In a letter written to University President Maurie McInnis and Provost Scott Strobel, signatories addressed the “collision of two opposing forces: extraordinary financial strength and runaway bureaucratic expansion.”

…Professor Juan de la Mora, a letter’s signee, said that a significant number of Yale professors believe that the institution is using funding for “improper” purposes and neglecting the school’s founding principles of emphasizing faculty and students.

…Professor of Philosophy Daniel Greco mirrored these sentiments, recognizing the increase in administrative spending in Yale’s budget.

Greco said these spending habits have faculty “puzzled,” as they hear of the money being spent but do not see a change in their day-to-day work.

Professor of Law Sarath Sanga, author of the letter, wrote to the News that over the last two decades, “faculty hiring has stagnated while administrative ranks have by some estimates more than doubled–outpacing peer institutions.”

University are supposed to be faculty-led but over the last several decades most have been taken over by administrators–perhaps we shall see some change.

AI Goes to College…for the Free Money

Last year, the state [CA] chancellor’s office estimated 25 percent of community college applicants were bots.

Everyone understands that students are using AI; sometimes to help them learn, sometimes to avoid learning. What I didn’t appreciate is that community colleges offering online courses are being flooded with AI bots who are taking the courses:

The bots’ goal is to bilk state and federal financial aid money by enrolling in classes, and remaining enrolled in them, long enough for aid disbursements to go out. They often accomplish this by submitting AI-generated work. And because community colleges accept all applicants, they’ve been almost exclusively impacted by the fraud.

The state has launched a Bladerunner-eque “Inauthentic Enrollment Mitigation Taskforce” to try to combat the problem. This strikes me, however, as more of a problem on the back-end of government sending out money without much verification. It’s odd to make the community colleges responsible for determining who is human. Stop sending the money to the bots and the bots will stop going to college.

Sam Altman, as usual, is ahead of the game.

The macroeconomics of tariff shocks

There is a new paper by Adrien Auclert, Matthew Rognlie, and Ludwig Straub. It seems timely?:

We study the short-run effects of import tariffs on GDP and the trade balance in an open-economy New Keynesian model with intermediate input trade. We find that temporary tariffs cause a recession whenever the import elasticity is below an openness-weighted average of the export elasticity and the intertemporal substitution elasticity. We argue this condition is likely satisfied in practice because durable goods generate great scope for intertemporal substitution, and because it is easier to lose competitiveness on the global market than to substitute between home and foreign goods. Unilateral tariffs tend to improve the trade balance, but when other countries retaliate the trade balance worsens and the recession deepens. Taking into account the recessionary effect of tariffs dramatically lowers the optimal unilateral tariff level derived in standard trade theory.

I wonder what the policy implications might be. Here is a good thread on the paper.

The Prophet’s Paradox

The political problem of disaster preparedness is especially acute for the most useful form, disaster avoidance. The problem with avoiding a disaster is that success often renders itself invisible. The captain of the Titanic is blamed for hitting the iceberg, but how much credit would he have received for avoiding it?

Consider a pandemic. When early actions—such as testing and quarantine, ring vaccination, and local lockdowns—prevent a pandemic, those inconvenienced may question whether the threat was ever real. Indeed, one critic of this paper pointed to warnings about ozone depletion and skin cancer in the 1980s as an example of exaggeration and a predicted disaster that did not happen. Of course, one of the reasons the disaster didn’t happen was the creation of the Montreal Protocol to reduce ozone-depleting substances (Jovanović et al. 2019; Tabarrok and Canal 2023). The Montreal Protocol is often called the world’s most successful international agreement, but it is not surprising that we don’t credit it for skin cancers that didn’t happen. I call this the prophet’s paradox: the more the prophet is believed beforehand, the less they are credited afterward.

The prophet’s paradox can undermine public support for proactive measures. The very effectiveness of these interventions creates a perception that they were unnecessary, as the dire outcomes they prevented are never realized. Consequently, policymakers face a challenging dilemma: the better they manage a potential crisis, the more likely it is that the public will perceive their actions as overreactions. Success can paradoxically erode trust and make it more difficult to implement necessary measures in future emergencies. Hence, politicians are paid to deal with emergencies not to avoid them (Healy and Malhotra 2009).

Since politicians are incentivized to deal with rather than avoid emergencies it is perhaps not surprising to find that this attitude was built into the planning process. Thus, the UK COVID Inquiry (2024, 3.17) found that:

Planning was focused on dealing with the impact of the disease rather than preventing its spread.

Even more pointedly Matt Hancock testified (UK COVID Inquiry 2024, 4.18):

Instead of a strategy for preventing a pandemic having a disastrous effect, it [was] a strategy for dealing with the disastrous effect of a pandemic.

From my paper, Pandemic preparation without romance.

My excellent Conversation with Chris Dixon

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

Chris Dixon believes we’re at a pivotal inflection point in the internet’s evolution. As a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz and author of Read Write Own, Chris believes the current internet, dominated by large platforms like YouTube and Spotify, has strayed far from its decentralized roots. He argues that the next era—powered by blockchain technology—can restore autonomy to creators, lower barriers for innovation, and shift economic power back to the network’s edges.

Tyler and Chris discuss the economics of platform dominance, how blockchains merge protocol-based social benefits with corporate-style competitive advantages, the rise of stablecoins as a viable blockchain-based application, whether Bitcoin or AI-created currencies will dominate machine-to-machine payments, why Stack Overflow could be the first of many casualties in an AI-driven web, venture capital’s vulnerability to AI disruption, whether open-source AI could preserve national sovereignty, NFTs as digital property rights system for AIs, how Kant’s synthetic a priori, Kripke’s modal logic, and Heidegger’s Dasein sneak into Dixon’s term‑sheet thinking, and much more.

Most of the talk was about tech of course, but let’s cut right to the philosophy section:

COWEN: What’s your favorite book in philosophy?

DIXON: I’ve actually been getting back into philosophy lately. I did philosophy years ago in grad school. Favorite book, man. Are you into philosophy?

COWEN: Of course, yes. Plato’s Dialogues; Quine, Word and Object; Parfit, Reasons and Persons; Nozick. Those are what come to my mind right away.

DIXON: Yes. I did analytic philosophy. I actually was in a graduate school program and dropped out. I did analytic philosophy. Actually, Quine was one of my favorites — Word and Object and Two Dogmas of Empiricism, all those kinds of things. I like Donald Davidson. Nozick — I loved Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Reading that with Rawls is a great pairing. I used to love Wittgenstein, both early and later. I was into logic, so Frege and Russell. This was a grad school.

Now I’m trying to finally understand continental philosophy. I never understood it. I’ve actually spent the last three months in a philosophy phase. I’ve been watching a lot of videos. Highly recommend this. Do you know Bryan Magee?

COWEN: Sure, yes.

DIXON: Amazing. I watched all of his videos. This guy, Michael Sugrue, was a Princeton professor — great videos on continental philosophy. I’ve been reading — it sounds pretentious; I’m not saying I understand this or I’m an expert on it, but I’m struggling in reading it. I’m trying to read Being and Time right now — Heidegger. I really like Kripke. I follow Kripke. I liked his books a lot. Nelson Goodman was one of my favorites. Funny enough, I just bought it again — Fact, Fiction, and Forecast. Kripke — Naming and Necessity is his legendary book on reference and language.

COWEN: I’ve never been persuaded by that one. It always felt like sleight of hand to me. He’s very, very smart. He might be the sharpest philosopher, but I like the book on Wittgenstein better.

DIXON: He basically invented modal logic. I don’t know if you know that story. He was in high school, something.

COWEN: He was 15 years old, I heard. Yes.

DIXON: [laughs] He’s like a true prodigy. Like a lot of philosophy, you have to take it in the context, like Naming and Necessity I think of as a response — gosh, I’m forgetting the whole history of it, but as I recall, it was a response to the descriptive theory of reference, like Russell. Anyways, I think you have to take these things in a pairing.

Actually, last night I was with a group of people. I got a lecture on philosophy, and it was great because he went through Hume, Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche. I don’t want to go too much into that, but I’ve always struggled with Kant. Then he went into Hegel and explained that Hegel struggled with Kant in the same way that I did, and then improved on it. I’m not trying to go into details of this; it’s too much. The point is, for me, a lot of it has to be taken in as a dialogue between thinkers over multiple periods.

COWEN: Are you getting anything out of Heidegger? Because I sometimes say I’ve looked at every page of that book, but I’m not sure I’ve read it.

DIXON: It’s a good question. I have a friend who’s really into it, and we’ve been spending time together, and he’s trying to teach me. If you want, I’ll send you some videos that I think are really good.

COWEN: That’d be great.

DIXON: They’ve helped me a lot. I’ve always got it from an intellectual history point of view. If you want to follow the history of postmodernism, there’s Heidegger and then Derrida, and just what’s going on in the academy today with relativism and discourse and hermeneutics. I think it’s modern political implications that were really probably kicked off by Nietzsche and then Heidegger. I’ve always understood in that sense.

What I struggle with, and I understand him as a theory of psychology, I think of describing the experience of the Dasein and being-in-the-world. To me, it’s an interesting theory of psychology. You’re thrown into the world. This whole idea is very appealing to me. Just that whole story he tells — you’re thrown into the world, ready at hand versus present at hand. I think this idea of knowing how versus knowing that, different kinds of knowledge is a very interesting idea. Do you watch John Vervaeke?

COWEN: No.

You will find the (very interesting) tech segments all over the rest of the dialogue. And I am happy to refer you all to the new paperback edition of Chris’s new book Read Write Own: Building the Next Era of the Internet.

Smith Reviews Stiglitz

Vernon Smith reviews Joe Stiglitz’s book The Road to Freedom:

Stiglitz did work in the abstract intellectual theoretical tradition of neoclassical economics showing how the standard results were changed by asymmetric or imperfect information. He is oblivious, however, to the experimental lab and field empirical research showing that agent knowledge of all such information is neither necessary nor sufficient for a market to converge to competitive supply-and-demand equilibrium outcomes.

Consequently, both the standard and the modified theories are irrelevant because buyers and sellers in possession only of dispersed, private, decentralized, value information easily converge to competitive price-quantity allocations in experimental markets over time via learning in repeat transactions.

…The first experiments, showing that complete WTP/WTA information was not necessary, were reported in Smith (1962), and none of us could any longer accept the standard and Stiglitz-modified theories. Further experiments, showing that such information was not sufficient, and that equilibrium prices need not require that markets clear, were reported in Smith (1965). (For propositions summarizing and evaluating observed empirical regularities in these experimental markets, see Vernon L. Smith, Arlington Williams, W. K. Bratt, and M. G. Vannoni, 1982, “Competitive Market Institutions: Double Auctions vs. Sealed Bid-Offer Auctions,” American Economic Review 72, no. 1, 58–77; and Vernon L. Smith, 1991, Papers in Experimental Economics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.) It was natural, in the first market experiments, to investigate those questions, such as the information state of traders, that were central to the abstract economic theory of the time.

So, the Akerlof-Stiglitz modifications of theory were founded on a false conditional and thus were not germane to practical market performance. They were born falsified.

…The needed policy implications are quite clear, and they have nothing to do with Stiglitz’s market failure and everything to do with how markets function. Indeed, the appropriate policy recommendation is to fully support the market-system maximization of prosperity, as did Friedman and Hayek, then use incentive mechanisms to improve the relative positions of those who are disadvantaged in that system. Never kill the goose that lays eggs of gold.

Rachel Glennerster calls for reforming foreign aid

Aid agencies already try to cover too many countries and sectors, incurring high costs to set up small programs. Aid projects are far too complicated, resembling a Christmas tree weighed down with everyone’s pet cause. With less money (and in the US, very few staff), now is the time to radically simplify. By choosing a few highly cost-effective interventions and doing them at large scale in multiple countries, we would ensure

- aid funds are spent on highly effective projects;

- we benefit from the substantial economies of scale seen in development;

- a much higher proportion of aid money goes to recipient countries, with less spent on consultants; and

- politicians and the public can more easily understand what aid is being spent on, helping build support for aid.

The entire piece is excellent.

Congratulations to the 2025 John Bates Clark Medalist Stefanie Stantcheva

Awesome choice, she is one of my favorite economists, and she is also a super-nice person. Here is the report and list of winners, here are previous mentions on MR.