Category: Economics

Arrived in my pile

Sebastian Mallaby, The Man Who Knew: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan.

Self-recommending, I will start it as soon as possible.

Peter Navarro outlines the Trump economic plan

To score the benefits of eliminating trade deficit drag, we don’t need any complex computer model. We simply add up most (if not all) of the tax revenues and capital expenditures that would be gained if the trade deficit were eliminated. We have modeled only the impacts of implicit profits and wages, not any other economic aspect of the increased activity.

Trump proposes eliminating America’s $500 billion trade deficit through a combination of increased exports and reduced imports. Again assuming labor is 44 percent of GDP, eliminating the deficit would result in $220 billion of additional wages. This additional wage income would be taxed at an effective rate of 28 percent (including trust taxes), yielding additional tax revenues of $61.6 billion.

In addition, businesses would earn at least a 15% profit margin on the $500 billion of incremental revenues, and this translates into pretax profits of $75 billion. Applying Trump’s 15% corporate tax rate, this results in an additional $11.25 billion of taxes.

Emphasis is added by this author.

Here is the full document (pdf). Here is my earlier profile of Peter Navarro. For the pointer I thank the excellent Binyamin Appelbaum.

Addendum: Scott Sumner comments.

Sentences about macroeconomics

From Brinca, Chari, Kehoe, and McGrattan, there is a new NBER paper “Accounting for Business Cycles“:

First with the notable exception of the United States, Spain, Ireland, and Iceland, the Great Recession was driven primarily by the efficiency wedge. Second, in the Great Recession, the labor wedge plays a dominant role only in the United States, and the investment wedge plays a dominant role in Spain, Ireland, and Iceland. Third, in the recessions of the 1980s, the labor wedge played a dominant role only in France, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and New Zealand. Finally, in the Great Recession the efficiency wedge played a much more important role and the investment wedge played a less important role than they did in the recessions of the 1980s.

You don’t have to agree with each and every claim there to see that a simple AS-AD model won’t give you enough structure to seriously address such questions. And:

The first misconception is that efficiency wedges in a prototype model can only come from technology shocks…In our judgment, by far the least interesting interpretation of efficiency wedges is as narrowly interpreted shocks to the blueprints governing individual firm production functions.

As a good first-order approximation, everything you read about “real business cycle theory” from its non-practitioners in the popular realm is wrong. Except the very phrase “real business cycle theory” isn’t even the correct term here. Better would be “contemporary macroeconomics,” although then the sense-reference distinction is going to play havoc with the first sentence of this paragraph.

Power Poses Are Dead

Dana Carney one of the co-authors of the famous paper (462 citations) that led to the famous TED talk (36 million views) and innumerable articles in the popular press on “power poses” (e.g. This Simple ‘Power Pose’ Can Change Your Life And Career) writes that after reviewing the evidence:

Dana Carney one of the co-authors of the famous paper (462 citations) that led to the famous TED talk (36 million views) and innumerable articles in the popular press on “power poses” (e.g. This Simple ‘Power Pose’ Can Change Your Life And Career) writes that after reviewing the evidence:

- 1. I do not have any faith in the embodied effects of “power poses.” I do not think the effect is real.

- 2. I do not study the embodied effects of power poses.

- 3. I discourage others from studying power poses.

- 4. I do not teach power poses in my classes anymore.

- 5. I do not talk about power poses in the media and haven’t for over 5 years (well before skepticism set in)

- 6. I have on my website and my downloadable CV my skepticism about the effect and links to both the failed replication by Ranehill et al. and to Simmons & Simonsohn’s p-curve paper suggesting no effect. And this document.

This cannot have been easy to write. Bravo.

Is American Pet Health Care (Also) Uniquely Inefficient?

That is the title of the new NBER paper by Liran Einav, Amy Finkelstein, and Atul Gupta, here is the abstract:

We document four similarities between American human healthcare and American pet care: (i) rapid growth in spending as a share of GDP over the last two decades; (ii) strong income-spending gradient; (iii) rapid growth in the employment of healthcare providers; and (iv) similar propensity for high spending at the end of life. We speculate about possible implications of these similar patterns in two sectors that share many common features but differ markedly in institutional features, such as the prevalence of insurance and of public sector involvement.

Note that the number of veterinarians doubled from 1996 to 2013. The authors do not seem to have data on whether cats and dogs live longer in the United States, but I have a surmise…

Here are ungated copies of the paper.

Is “hard Brexit” becoming more or less likely?

You can argue it either way. On one hand, the forward march of the UK economy, and the inability to develop a coherent negotiating position, militate in favor of a relatively quick and condition-less Brexit. The European Union is not offering any very flexible intermediate deals, perhaps to punish future would-be leavers. On the other hand, the consequences would be sobering (FT):

Research by the FT shows the scale of the UK-based banks using passporting to sell into the EU. The group of 96 banks has assets of £7.5tn, directly employ more than 590,000 people and make annual profits of around £50bn.

Bank executives say EU passporting makes up 20-25 per cent of the London business of international investment banks, including the five big US players, who have assets of £1.5tn and staff of 21,000 in their UK-based banks, and the two big Swiss, which have assets of £415bn and staff of more than 6,000.

And:

…John Holland-Kaye, chief executive of Heathrow, warned that leaving the EU customs union would “add massive overhead” for businesses and port operators. “Can you imagine operating something like the Euro[tunnel] if you had to suddenly build in all these checks in place? It would be completely unmanageable,” he told the FT.

This explainer of the “gravity model of trade” shows the UK could not make up lost EU business elsewhere in the world. Oil and a few other commodities aside, you trade with the countries that are next to you.

Overall, the Brexit stakes are higher than a few months ago, and that is making the final outcome harder not easier to predict.

Are lies better than hypocrisy?, with special reference to some current events

When should you place a higher penalty on transparently false outright repeated lies, and when should you be more upset by hypocrisy, namely a mix of altruism and self-interest and greed and defensiveness, bundled with self-deception and pawned off to everyone including yourself as sheer goodness? In recent times the question has taken on further import.

“Here’s the part of the 2016 story that will be hardest to explain after it’s… over: Trump did not deceive anyone.”

reporters take Trump literally and not seriously. We take Trump seriously but not literally.

in general, i prefer liars to hypocrites. A liar knows the truth and is cold-bloodedly trying to deceive you, probably for material profit or personal advantage, or malevolence – but in himself he knows the truth and so the situation is less unreal than with the hypocrite; for the hypocrite’s motive is often self-righteousness mingled with material profit and personal advantage. And the hypocrite believes his own lies, so the situation is wholly unreal, saturated with deception. With the liar one can at least guess there is a real human being somewhere behind the lies, watching, calculating; and sometimes in the midst of the deception one catches this real human being’s eye, and there is a moment of mutual recognition – that he is lying and he knows she is lying, and you know too, but of course neither will say so. With the hypocrite, all is false – through and through deception.

For purposes of illumination, say you treat this as a principal-agent problem. You sometimes prefer if your children lie to you transparently than if they are more deviously hypocritical, even if the lies in the former case are greater. The former case establishes a precedent that you can see through their claims, and they will not try so hard to disguise the fraud. So transparent lies about taking out the garbage are excused if you know you can see through the later claims about drugs and drink and prepping for the SAT.

You are more worried about the hypocrite when you see bigger decisions and announcements down the road than what is being faced now. You are more worried about the hypocrite when you fear disappointment, and have experienced disappointment repeatedly in the past. You are more worried about the hypocrite when you fear it is all lies anyway. Lies, in a way, give you a chance to try out “the liar relationship,” whereas hypocrisy does not. You thus fear that hypocrisy may lead to a worse outcome down the road or at the very least more anxiety along the way.

But note: for a more institutional and distanced principal-agent relationship, it is often incorrect, and indeed dangerous, to rely on your intuitions from personalized principal-agent problems.

When it comes to how the agent speaks to allies and enemies, you almost always should prefer hypocrisy to bald-faced lies. The history and practice of diplomacy show this. Allies and enemies, especially from other cultures, don’t know how to process the lies the way you can process the blatant lies of your children, friends, and spouse. They will think some of these lies are mere hypocrisy and that can greatly increase uncertainty and maybe lead to open conflict. North Korea aside, the prevailing international equilibrium is “hypocrisy only,” and those are the signals everyone has decades of experience in reading.

Josh Barro tweeted:

People pretending to be better than they are is what holds society together.

International society too.

There is such a hullaballoo in my Twitter feed every day about the lies. “It is now time to expose the lies!” I feel sad when I read this, because many of the American people already are putting up with the lies or even welcoming them. I do not see that as a correct course of action, as it is confusing personal morality with the abstract rules and principles that underlie social order (which is what voters almost always do, by the way). We need continuing hypocrisy in the international order, and thus from our distanced political agents, even if we don’t want more of it in our personal lives.

I do not see enough people trying to understand lies vs. hypocrisy. In fact it is tough for many people to make this leap, because doing so requires a Hayekian stress on the distinction between the personal and the abstract political and rules-based order. That distinction does not always come easily to the non-Hayekians who comprise most of my Twitter feed. They are very quick to invoke their own personal morality to attempt to settle political disputes.

Note also that if citizens care more about hypocrisy than lies, the media will in turn be harsher with hypocrisy than outright lies. Some foundations will be covered (and criticized) more than others, even if the less-covered foundation has done more wrong and in a more blatant manner. Covering hypocrisy also usually involves a longer story with more successive revelations and more twists and turns and narrative suspense and room for ambiguity and competing interpretations.

Furthermore, in this equilibrium the defenders of the morality of the hypocritical agent will in fact make things worse for that agent. The hypocrisy will become not just a personal hypocrisy of the agent, but rather a broader, almost conspiratorial hypocrisy of greater society. So the more you think one (hypocritical) agent is getting unfair press coverage, and the more you defend that agent, the worse you make it for that agent.

Talking about the lies of the lying agent may help that agent win popularity, by turning voter attention to the “lies vs. hypocrisy” framing rather than “experience vs. incompetence.” The lying agent has at least some chance in the former battle, but not much in the latter.

I wonder if earnest Millennials have a special dislike of hypocrisy.

Think about it. Or if not, at least pretend you will.

Stephen J. Entin on raising estate taxes

The transfer [estate] taxes are highly distortive of economic activity. In fact, they probably do the most damage to output and income per dollar of revenue raised of all the taxes in the U.S. tax system. There are two reasons. First, they are an additional layer of tax on saving and investment, activities that are highly sensitive to taxation and very likely to shrink in response to the tax. Second, the transfer taxes are levied at very high, steeply graduated marginal tax rates on a very narrow tax base. The high rates discourage saving and investment at the margin, while the average tax rate and tax revenues are held down by the credit. A tax that has a large differential between its average and marginal tax rates does far more damage per dollar of revenue raised than a flatter rate tax on a broader base.

Here is the full study and pdf. The pointer is from Alex T.

Quant trading economies of scale someone should give Doug his own blog

There are a few possible routes to establishing a monopoly in quant trading. Here’s one that seems to work really well. It’s kind of hard to explain, so bear with me. Many trading signals reliably predict prices, but not strongly enough to overcome transaction costs (i.e. exchange fees, clearing fees, liquidity costs, etc.). A stock can moves up or down $.01 in the next period, your trading signals predicts the right direction 60% of the time, and transaction costs average $.0025. Unfortunately after costs, you’ll end up losing $.0005 per trade, so it’s not a viable strategy.

But let’s say you’ve got three uncorrelated trading signals just like it. If you wait until all three point in the same direction, now there’s a 94% of the stock moving in your favor. You easily clear the transaction cost threshold and neatly make $.0063 per trade. When you gather together multiple uncorrelated signals, the whole becomes worth much more than the sum of the parts.

This is basically how a company like Renaissance Technologies operates. It has hundreds of people working in silo’d groups. Each group contributes to the overall fund’s strategy, but are largely unaware of what the others are doing. Alone any single group would probably not have a viable standalone strategy. That’s a big deterrent to people leaving, starting from scratch is really hard. And there’s only a few other major companies in Renaissance’s league, where they’re already strong enough to make money off of marginal signals. It’s a chicken-and-egg problem. To become viable in the space you need to accumulate a whole bunch of signals, but to attract a critical mass of talent with signals you need to already have a viable strategy running.

That one was “from the comments.“

Is China’s anti-corruption drive sincere?

Or just a way to get rid of political opponents? The news on this front is by no means entirely bad. Xi Lu and Peter L. Lorentzen report:

In order to maintain popular support or at least acquiescence, autocrats must control the rapacious tendencies of other members of the governing elite. At the same time, the support of this elite is at least as important as the support of the broader population. This creates difficult tradeoffs and limits the autocrat’s ability to enforce discipline. We explore this issue in the context of Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s ongoing anti-corruption campaign. There have been two schools of thought about this campaign. One holds that it is nothing but a cover for intra-elite struggle and a purge of Xi’s opponents, while the other finds more credibility in the CCP’s claim that the movement is sincere. In this article, we demonstrate three facts, using a new dataset we have created. First, we use the political connections revealed by legal documents and media reports to visualize the corruption network. We demonstrate that although many of the corrupt officials are connected, Xi’s most prominent political opponent, Bo Xilai, is less central by any network measure than other officials who were not viewed as challenging Xi’s leadership. Second, we use a recursive selection model to analyze who the campaign has targeted, providing evidence that even personal ties to top leaders provided little protection. Finally, using another comprehensive dataset on the prefectural-city level, we show that the provinces later targeted by the corruption campaign differed from the rest in important ways. In particular, it appears that promotion patterns departed from the growth-oriented meritocratic selection procedures evidence in other provinces. Overall, our findings contradict the factional purge view and are more consistent with the view that the campaign is indeed primarily an attempt to root out systemic corruption problems.

The pointer is from the excellent Kevin Lewis.

From the comments, how to hit it big?

I am not endorsing these claims, but I do enjoy a good rant. It is an object lesson in showing how (some) people think about jobs, status, rivalry, and money.

First venture capital is generally consider where washed-out Wall Streeters go, when they can’t cut it in real finance. Very few b-school students start out trying to get into VC. And no, generally Silicon Valley people are not nearly as smart as HFT/algo quants. The type of kids who go to Google or Facebook are generally the Ivy CS students from the upper half of their class who are good at white-boarding problems (e.g. reverse a linked list). The truly brilliant kids, Putnam winners, math olympiads, core kernel contributors, etc. disproportionately go the quant route. (In which at least half will wind up in Chicago).

SV is generally a worse deal than HFT or quant trading. Starting comp is at least 50% higher than the big five tech firms, and goes up at a much faster rate. And definitely way higher than startups, which nearly always under-pay. It’s true in tech you can become a multibillionaire, but that’s extremely unlikely even for the most talented. In general SV is a bad deal for everyone except the small set of people lucky or connected enough to be at the top. Outside founder level, virtually no one gets rich from startups anymore. The equity and options comp is pathetic at best, if not outright fraudulent. (“You’ll be getting 1% of outstanding shares… from this round…”). Even founders have to live on 70k salaries in the Bay Area, then are frequently screwed over or cliff’d by their VCs. For every Google, heck for every Apigee, there’s a thousand no-name flame-outs, where no one but the VCs walk away with a dime.

Compare to quant trading. Compensation is cold hard cash, usually paid out annually, if not quarterly. Not lottery ticket equity with four year cliffs, unlimited dilution and byzantine share classes. Most comp is directly tied to individual trading performance, with clear results from trading everyday. No politics, extremely meritocratic, no being at the random whims of whether your app takes off fast enough to overcome your burn rate. Firms actually compete for talent and pay accordingly, instead of colluding to keep wages suppressed. Unless your ambition is to top the Forbes list, HFT’s a much better deal for someone extremely intelligent like a Math Olympiad. The probability of making “f-you money” before 40 is at least an order of magnitude higher as a prop quant than in the Valley.

That is from Doug.

Gelman on the Replication Crisis and Social Media

This Andrew Gelman post on the replication crisis and the role that blogs have played in generating that crisis starts off slow but just builds and builds until by the end it’s like holy rolling thunder. Here is just one bit:

Fiske is annoyed with social media, and I can understand that. She’s sitting at the top of traditional media. She can publish an article in the APS Observer and get all this discussion without having to go through peer review; she has the power to approve articles for the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; work by herself and har colleagues is featured in national newspapers, TV, radio, and even Ted talks, or so I’ve heard. Top-down media are Susan Fiske’s friend. Social media, though, she has no control over. That’s must be frustrating, and as a successful practioner of traditional media myself (yes, I too have published in scholarly journals), I too can get annoyed when newcomers circumvent the traditional channels of publication. People such as Fiske and myself spend our professional lives building up a small fortune of coin in the form of publications and citations, and it’s painful to see that devalued, or to think that there’s another sort of scrip in circulation that can buy things that our old-school money cannot.

But let’s forget about careers for a moment and instead talk science.

When it comes to pointing out errors in published work, social media have been necessary. There just has been no reasonable alternative. Yes, it’s sometimes possible to publish peer-reviewed letters in journals criticizing published work, but it can be a huge amount of effort. Journals and authors often apply massive resistance to bury criticisms.

If you are interested in the replication crisis or the practice of science read the whole thing.

Aside from the content, I also love Gelman’s post for brilliantly mirroring its metaphor in its structure. Very meta.

Why do people play chess again?

According to Donner: “The whole point of the game [is] to prevent an artistic performance.” The former world champion Garry Kasparov makes the same point. “The highest art of the chess player,” he says, “lies in not allowing your opponent to show you what he can do.” Always the other player is there trying to wreck your masterpiece. Chess, Donner insists, is a struggle, a fight to the death. “When one of the two players has imposed his will on the other and can at last begin to be freely creative, the game is over. That is the moment when, among masters, the opponent resigns. That is why chess is not art. No, chess cannot be compared with anything. Many things can be compared with chess, but chess is only chess.”

That is Stephen Moss at The Guardian. Along related lines, I very much enjoyed Daniel Gormally’s Insanity, Passion, and Addiction: A Year Inside the Chess World. It’s one of my favorite books of the year so far, but it’s so miserable I can’t recommend it to anyone. It’s a book about chess, and it doesn’t even focus on the great players. It’s about the players who are good enough to make a living — ever so barely — but not do any better. It serves up sentences such as:

Surely the money in chess is so bad that this can’t be all you do for a living? But in fact in my experience, the majority of chess players rated over 2400 tend to just do chess. If not playing, then something related to it, like coaching or DVDs. That’s because we’re lazy, so making the monumental effort of a complete change in career is just too frightening a prospect. So we stick with chess, even though the pay tends to be lousy, because most of our friends and contacts are chess players. Our life is chess. As a rough estimate, I would say there are as many 2600 players making less than £20,000 a year.

And:

Stability. I had this conversation with German number one Arkadij Naidisch at a blitz tournament in Scotland about a year ago. (there I go, name-dropping again.) He suggested that a lot of people don’t achieve their goals because they just aren’t stable enough. They’ll have a fantastic result somewhere, but then that’ll be let down by a terrible tournament somewhere else.

…The problem is it’s hard to break out of the habits of a lifetime. Many times at home I’ve said to myself while sitting around depressed about my future and where my chess is going, “tomorrow will be different. I’ll get up and study six-eight hours studying chess.” But it never happens.

Overall biography and autobiography are far too specialized in the lives of the famous and successful.

Firms that Discriminate are More Likely to Go Bust

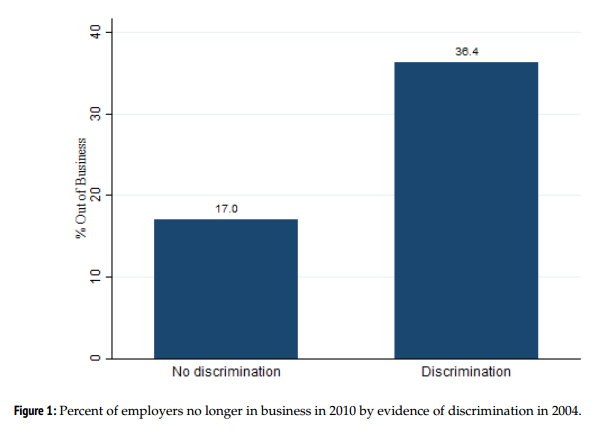

Discrimination is costly, especially in a competitive market. If the wages of X-type workers are 25% lower than those of Y-type workers, for example, then a greedy capitalist can increase profits by hiring more X workers. If Y workers cost $15 per hour and X workers cost $11.25 per hour then a firm with 100 workers could make an extra $750,000 a year. In fact, a greedy capitalist could earn more than this by pricing just below the discriminating firms, taking over the market, and driving the discriminating firms under. The basic logic of employer wage discrimination was laid out by Becker in 1957. The logic implies that discrimination is costly, especially in the long-run, not that it doesn’t happen.

A nice test of the theory can be found in a paper just published in Sociological Science, Are Business Firms that Discriminate More Likely to Go Out of Business? The author, Devah Pager, is a pioneer in using field experiments to study discrimination. In 2004, she and co-authors, Bruce Western and Bart Bonikowski, ran an audit study on discrimination in New York using job applicants with similar resumes but different races and they found significant discrimination in callbacks. Now Pager has gone back to that data and asks what happened to those firms by 2010? She finds that 36% of the firms that discriminated failed but only 17% of the non-discriminatory firms failed.

A nice test of the theory can be found in a paper just published in Sociological Science, Are Business Firms that Discriminate More Likely to Go Out of Business? The author, Devah Pager, is a pioneer in using field experiments to study discrimination. In 2004, she and co-authors, Bruce Western and Bart Bonikowski, ran an audit study on discrimination in New York using job applicants with similar resumes but different races and they found significant discrimination in callbacks. Now Pager has gone back to that data and asks what happened to those firms by 2010? She finds that 36% of the firms that discriminated failed but only 17% of the non-discriminatory firms failed.

The sample is small but the results are statistically significant and they continue to hold controlling for size, sales, and industry.

As Pager notes, the cause of the business failure might not be the discrimination per se but rather that firms that discriminate are hiring using non-rational, gut feelings while firms that don’t discriminate are using more systematic and rational methods of hiring.

As she concludes:

…whether because of discrimination or other associated decision making, we can more confidently conclude that the kinds of employers who discriminate are those more likely to go out of business. Discrimination may or may not be a direct cause of business failure, but it seems to be a reliable indicator of failure to come.

Does varying rainfall make people collectivists?

Lewis Davis has a newly published paper on that topic with the more elegant title “Individual Responsibility and Economic Development: Evidence from Rainfall Data.” Here is the abstract:

This paper estimates the effect of individual responsibility on economic development using an instrument derived from rainfall data. I argue that a taste for collective responsibility was adaptive in preindustrial societies that were exposed to high levels of agricultural risk, and that these attitudes continue to influence contemporary social norms and economic outcomes. The link between agricultural risk and collective responsibility is formalized in a model of optimal parental socialization effort. Empirically, I find a robust negative correlation between rainfall variation, a measure of exogenous agricultural risk, and a measure of individual responsibility. Using rainfall variation as an instrument, I find that individual responsibility has a large positive effect on economic development. The relationships between rainfall variation, individual responsibility and economic development are robust to the inclusion of variables related to climate and agricultural and institutional development.

This kind of investigation is always going to be fraught with uncertainty and also controversy, given imperfections of data and methods. Nonetheless I find this one of the more plausible macro-historical hypotheses, perhaps because of my own experience in central Mexico, where varying rainfall still is the most important economic event of the year, though it is rapidly being supplanted by the variability of tourist demand for arts and crafts. And yes, they are largely collectivist, at least at the clan level, with extensive systems of informal social insurance and very high implicit social marginal tax rates on accumulated wealth.

Have you noticed it rains a lot in England?

Here are earlier and ungated/less gated versions of the paper.