Category: Economics

Let’s think again about Dodd-Frank

That is my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

Looking at a broad swath of history, I see three major forces that can make financial systems safer: people being scared by recent events, solid economic growth and reduced debt in comparison to the value of equity. The financial crisis gave us the first on that list as perhaps its main “gift” (for now), but Dodd-Frank may have worsened economic growth problems.

On the plus side, we might like to think that Dodd-Frank improved the debt-equity balance by pushing banks to raise more capital. But that, too, now stands in doubt.

Last week Natasha Sarin and Lawrence H. Summers of Harvard University released a paper questioning whether Dodd-Frank has made big U.S. banks safer at all. The authors look at a variety of measures, including options prices, the ratio of market prices to book values, bank share volatility relative to overall market volatility, credit-default swap spreads and the value of preferred equity shares for banks. In every metric, it seems that the big banks are at least as risky as they were before the crisis, in part because they have lower capital values.

And this:

It’s a common economic prescription that regulation should insist that banks carry high levels of capital to withstand losses in bad times. But although Dodd-Frank raised statutory capital requirements, it may have drained banks of some of their true economic capital by regulating and sometimes prohibiting valuable banking activities. The ratio of market price to book value has declined for the biggest banks, and that is one sign of falling values for true economic capital, even though banks have met the letter of law by increasing capital as the regulations specified. Sarin and Summers note that measures of bank capital, as defined by regulators rather than the market, have little predictive power for bank failures.

Do read the whole thing.

Egalitarianism versus Online Education

The Department of Justice has sent a letter to UC Berkeley threatening a lawsuit unless the university modifies all of its free online educational materials to meet conditions of accessibility. In response the Vice Chancellor for Undergraduate Education writes:

…we have attempted to maximize the accessibility of free, online content that we have made available to the public. Nevertheless, the Department of Justice has recently asserted that the University is in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act because, in its view, not all of the free course and lecture content UC Berkeley makes available on certain online platforms is fully accessible to individuals with hearing, visual or manual disabilities.

…We look forward to continued dialog with the Department of Justice regarding the requirements of the ADA and options for compliance. Yet we do so with the realization that, due to our current financial constraints, we might not be able to continue to provide free public content under the conditions laid out by the Department of Justice to the extent we have in the past.

In many cases the requirements proposed by the department would require the university to implement extremely expensive measures to continue to make these resources available to the public for free. We believe that in a time of substantial budget deficits and shrinking state financial support, our first obligation is to use our limited resources to support our enrolled students. Therefore, we must strongly consider the unenviable option of whether to remove content from public access.

In short, the DOJ is saying that unless all have access, none can and UC Berkeley is replying that none will. I sympathize with UC Berkeley’s position. The cost of making materials accessible can be high and the cost is extremely high per disabled student. It would likely be much cheaper to help each disabled student on an individual basis than requiring all the material to be rewritten, re-formatted and reprogrammed (ala one famous example).

An even greater absurdity is that online materials are typically much easier to access than classroom materials even when they do not fully meet accessibility rules. How many teachers, for example, come with captions? (And in multiple languages?) How about volume control? How easy is it for the blind to get to campus? In theory, in-class materials are also subject to the ADA but in practice everyone knows that that is basically unworkable. I guarantee, for example, that professors throughout the UC-system routinely show videos or use powerpoints that do not meet accessibility guidelines. Thus, by raising the costs of online education, the most accessible educational format, the ADA may have the unintended consequence of slowing access. Put simply, raising the costs of online education makes it more difficult for anyone to access educational materials including the disabled.

Addendum: By the way, if you are wondering, all of MRU’s videos for our Principles of Microeconomics and Principles of Macroeconomics courses are captioned in English and most are also professionally captioned in Spanish, Arabic and Chinese.

Paul Krugman on Gary Johnson, libertarianism, and pollution

Paul Krugman is upset that many Millennials are toying with the idea of voting for Gary Johnson rather than Hillary Clinton. He offers a number of arguments, here is one of them:

What really struck me, however, was what the [Libertarian Party] platform says about the environment. It opposes any kind of regulation; instead, it argues that we can rely on the courts. Is a giant corporation poisoning the air you breathe or the water you drink? Just sue: “Where damages can be proven and quantified in a court of law, restitution to the injured parties must be required.” Ordinary citizens against teams of high-priced corporate lawyers — what could go wrong?

That is the opposite of the correct criticism. The main problem with classical libertarianism is that it doesn’t allow enough pollution. Under libertarian theory, pollution is a form of violent aggression that should be banned, as Murray Rothbard insisted numerous times. OK, but what about actual practice, once all those special interest groups start having their say? Historically, under the more limited government of the 19th century, it was big business that wanted to move away from unpredictable local and litigation-driven methods of control, and toward a more systematic regulatory approach at the national level. There is a significant literature on this development, starting with Morton Horwitz’s The Transformation of American Common Law.

If you think about it, this accords with standard industrial organization intuitions. Established incumbents prefer regulations that take the form of predictable, upfront high fixed costs, if only to limit entry. And to some extent they can pass those costs along to consumers and workers. The “maybe you can sue me, maybe you can’t” regime is more the favorite of thinly capitalized upstarts that have little to lose.

So under the pure libertarian regime, big business would come running to the federal government asking for systematic regulation in return for protection against the uncertain depredations of the lower-level courts. It is fine to argue the court-heavy libertarian regime would be unworkable for this reason, or perhaps it would collapse into a version of the status quo.

That would be a much more fun column: “Libertarian view untenable, implies too high a burden on polluters.” I’m not sure that would sway the Bernie Brothers however.

Some of the criticisms of libertarianism strike me as under-argued:

And if parents don’t want their children educated, or want them indoctrinated in a cult…Not our problem.

Rates of high school completion were below 70% for decades, until recently, in spite of compulsory education. Parents rescuing children from the neglect of the state seems at least as common to me as vice versa.

And what is the status quo policy on taking children away from parents who belong to “cults”? Unusual religions can be a factor in contested child custody cases (pdf), but in the absence of evidence of concrete harm, such as beatings or sexual abuse, the American government does not generally take children away from their parents, cult or not. Germany and Norway differ on this a bit, for the most part this is, for better or worse, the American way. That’s without electing Gary Johnson.

By the way, Gary Johnson slightly helps Hillary Clinton. Although probably not with New York Times readers.

Straight thinking about Bayer and Monsanto

That is my latest Bloomberg column, hardly anyone has a consistent and evidence-based view on this deal. Here is one bit:

Critics who dislike Monsanto for its leading role in developing genetically modified organisms and agricultural chemicals shouldn’t also be citing monopoly concerns as a reason to oppose the merger — that combination of views doesn’t make sense. Let’s say for instance that the deal raised the price of GMOs due to monopoly power. Farmers would respond by using those seeds less, and presumably that should be welcome news to GMO opponents.

Yet on the other side:

What does Bayer hope to get for its $66 billion, $128-a-share offer? The company has argued that it will be able to eliminate some duplicated jobs and expenses, negotiate better deals with suppliers and invest more funds in research and development. Maybe, but the broader reality is less cheery. There is a well-known academic literature, dating to the early 1990s, showing that acquiring firms usually decline in value after tender offers, especially after the biggest deals. Mergers do not seem to make companies more valuable or efficient.

And this:

The whole Bayer-Monsanto case is a classic example of how a vociferous public debate can disguise or even reverse the true issues at stake. If Bayer fails to close the deal for Monsanto, Bayer shareholders may be the biggest winners. The biggest losers from a failed deal may be its opponents, who will spend the rest of their lives in a world where misguided judgments of corporate popularity have increasing sway over laws and regulations.

Do read the whole thing.

Robert Shiller on Open Borders

Nobelist Robert Shiller writes that the next revolution will be an anti-national revolution:

For the past several centuries, the world has experienced a sequence of intellectual revolutions against oppression of one sort or another. These revolutions operate in the minds of humans and are spread – eventually to most of the world – not by war (which tends to involve multiple causes), but by language and communications technology. Ultimately, the ideas they advance – unlike the causes of war – become noncontroversial.

I think the next such revolution, likely sometime in the twenty-first century, will challenge the economic implications of the nation-state. It will focus on the injustice that follows from the fact that, entirely by chance, some are born in poor countries and others in rich countries. As more people work for multinational firms and meet and get to know more people from other countries, our sense of justice is being affected.

Oddly, however, Shiller’s argument focuses not on immigration but on trade agreements. Trade agreements, he argues, will equalize wages through the factor price-equalization theorem but to do this we need a strengthening of the welfare state. The latter part of the argument and how it resolves with the former is, shall we say, underdeveloped.

What is wrong with African cities?

In Africa this process seems not to work as well. According to one 2007 study of 90 developing countries, Africa is the only region where urbanisation is not correlated with poverty reduction. The World Bank says that African cities “cannot be characterised as economically dense, connected, and liveable. Instead, they are crowded, disconnected, and costly.”

I say the one big problem is premature deindustrialization:

What ties them [African cities] together, and sets them apart from cities elsewhere in the world, according to the Brookings Institution, an American think-tank, is that urbanisation has not been driven by increasing agricultural productivity or by industrialisation. Instead, African cities are centres of consumption, where the rents extracted from natural resources are spent by the rich. This means that they have grown while failing to install the infrastructure that makes cities elsewhere work.

That is from The Economist, the article is interesting throughout.

The culture that is Texas high school football

After Texas high school builds $60-million stadium, rival district plans one for nearly $70 million

Need I say more? I will nonetheless:

In Frisco, which neighbors Allen and McKinney, the district will pay $30 million over several years to use the Dallas Cowboys’ new 12,000-seat practice field for high school football and soccer games, as well as graduation ceremonies.

Here is a nice bit of fiscal illusion:

In McKinney [one of the stadium-building districts], school taxes for property owners amount to $1.63 per $100 of assessed valuation. The tax rate had been higher in the recent past, but it fell 5 cents this year, partly because the district had dropped some old debt. Because of the 5-cent decrease, district officials repeatedly note, property owners will see their taxes go down, even as the new stadium goes up.

Jim Buchanan would be proud. And it’s a good thing we have the public sector to protect us from negative-sum status-seeking games!

The original pointer is from Adam Minter.

Hail GMU’s visionary, Dan Klein

I will second Bryan Caplan’s post:

Last week, my colleague Dan Klein kicked off the Public Choice Seminar series. During the introduction, I recalled some of his early work. But only after did I realize how visionary he’s been.

In 1999, when internet commerce was still in its infancy, Klein published Reputation: Studies in the Voluntary Elicitation of Good Conduct. Seventeen years later, e-commerce towers before us, resting on a foundation of reputational incentives – everything from old-fashioned repeat business to two-sided smartphone reviews.

In 2003, long before Uber, Airbnb, or serious talk of driverless cars, Klein published The Half-Life of Policy Rationales: How New Technology Affects Old Policy Issues. This remarkable work explores how technological change keeps making old markets failures – and the regulations that arguably address them – obsolete. (Here’s the intro, co-authored with Fred Foldvary). Fourteen years later, the relevance of Klein’s thesis is all around us. Transactions costs no longer preclude peakload pricing for roads, decentralized taxis and home rentals, or full-blown caveat emptor for consumer goods. So why not?

I’m not going to say that Klein caused these amazing 21st-century developments. But he did foresee them more clearly than almost anyone. Hail Dan Klein!

Some of Dan’s work, and later work (much of which is covered at MR), you will find here and here. For instance, his later work on academic bias also was well ahead of its time and prefigured subsequent events, so this is actually a running streak.

The economic decline of bowling the culture that was America

Bowling alone and for peanuts too:

In 1964, “bowling legend” Don Carter was the first athlete in any sport to receive a $1 million endorsement deal ($7.6 million today). In return, bowling manufacturing company Ebonite got the rights to release the bowler’s signature model ball. At the time, the offer was 200x what professional golfer Arnold Palmer got for his endorsement with Wilson, and 100x what football star Joe Namath got from his deal with Schick razor. Additionally, Carter was already making $100,000 ($750,000) per year through tournaments, exhibitions, television appearances, and other endorsements, including Miller, Viceroys, and Wonder Bread.

…Of the 300 bowlers who competed in PBA events during the 2012-2013 season, a select few did surprisingly well. The average yearly salary of the top ten competitors was just below $155,000, with Sean Rash topping the list at $248,317. Even so, in the 1960s, top bowlers made twice as much as top football stars — today, as the highest grossing professional bowler in the world, Sean Rash makes significantly less than a rookie NFL player’s minimum base salary of $375,000.

In 1982, the bowler ranked 20th on the PBA’s money list made $51,690; today, the bowler ranked 20th earns $26,645.

The article, by Zachary Crockett, suggests numerous hypotheses for the economic decline of bowling, but ultimately the answer is not clear to me. I would suggest the null of “non-bowling is better and now it is better yet.” A more subtle point is that perhaps bowling had Baumol’s “cost disease,” but under some assumptions about elasticities a cost disease sector can shrink rather than ballooning as a share of gdp.

For the pointer I thank Mike Donohoo.

China facts of the day

Total outstanding mortgage loans rose more than 30 percent and new mortgage growth clocked in at 111 percent in the past year. Since June 2012, outstanding mortgage loans have grown at an annualized rate of 30 percent. Predictably, that’s pushed prices higher and higher.

In urban China, the average price per square foot of a home has risen to $171, compared to $132 in the U.S. In first-tier cities such as Beijing and Shenzhen, prices have increased by about 25 percent in the past year. A 100-city index compiled by SouFun Holdings Ltd. surged by a worrisome 14 percent in the last year. Developers are buying up land in some prime areas that would need to sell for $15,000 per square meter just to break even.

That is from Christopher Balding, there is more at the link. Might as much as 70% of Chinese household wealth be in housing? Here is some follow-up analysis.

Labor Force Participation and Video Games

Here is more from Erik Hurst discussing his new research:

On average, lower-skilled men in their 20s increased “leisure time” by about four hours per week between the early 2000s and 2015. All of us face the same time endowment, so if leisure time is increasing, something else is decreasing. The decline in time spent working facilitated the increase in leisure time for lower-skilled men. The way I measure leisure time is pretty broad; it includes participating in hobbies and hanging out with friends, exercising and watching TV, sleeping, playing games, reading, and so on.

Of that four-hours-per-week increase in leisure, three of those hours were spent playing video games! The average young, lower-skilled, nonemployed man in 2014 spent about two hours per day on video games. That is the average. Twenty-five percent reported playing at least three hours per day. About 10 percent reported playing for six hours per day. The life of these nonworking, lower-skilled young men looks like what my son wishes his life was like now: not in school, not at work, and lots of video games.

How do we know technology is causing the decline in employment for these young men? As of now, I don’t know for sure. But there are suggestive signs in the data that these young, low-skilled men are making some choice to stay home. If we go to surveys that track subjective well-being—surveys that ask people to assess their overall level of happiness—lower-skilled young men in 2014 reported being much happier on average than did lower-skilled men in the early 2000s. This increase in happiness is despite their employment rate falling by 10 percentage points and the increased propensity to be living in their parents’ basement.

It’s hard to distinguish “push” unemployment that is made more pleasant by video games from “pull” unemployment created by video games. I’m not even sure that distinction matters very much, at least if we aren’t talking about banning video games to increase employment. If elderly people started playing a lot of video games (as soon they will) would we worry that this was making retirement too much fun?

I’d be interested in knowing how much video games have displaced television. I watch more television than my kids, who play more video games. It’s not obvious that this is to their detriment.

Perhaps the issue is that video games like slot machines are so enticing that young people discount the future too heavily or don’t recognize the future cost of not being in the workforce. Maybe. Perhaps what we really need is a 3D, virtual reality, total sensory simulation, awesome video game that is so expensive that it encourages people to work.

Overall, the video game worry is a bit too reminiscent of the Dungeons and Dragons panic, or the earlier panics that books and radio were ruining children’s minds, for me to jump on board.

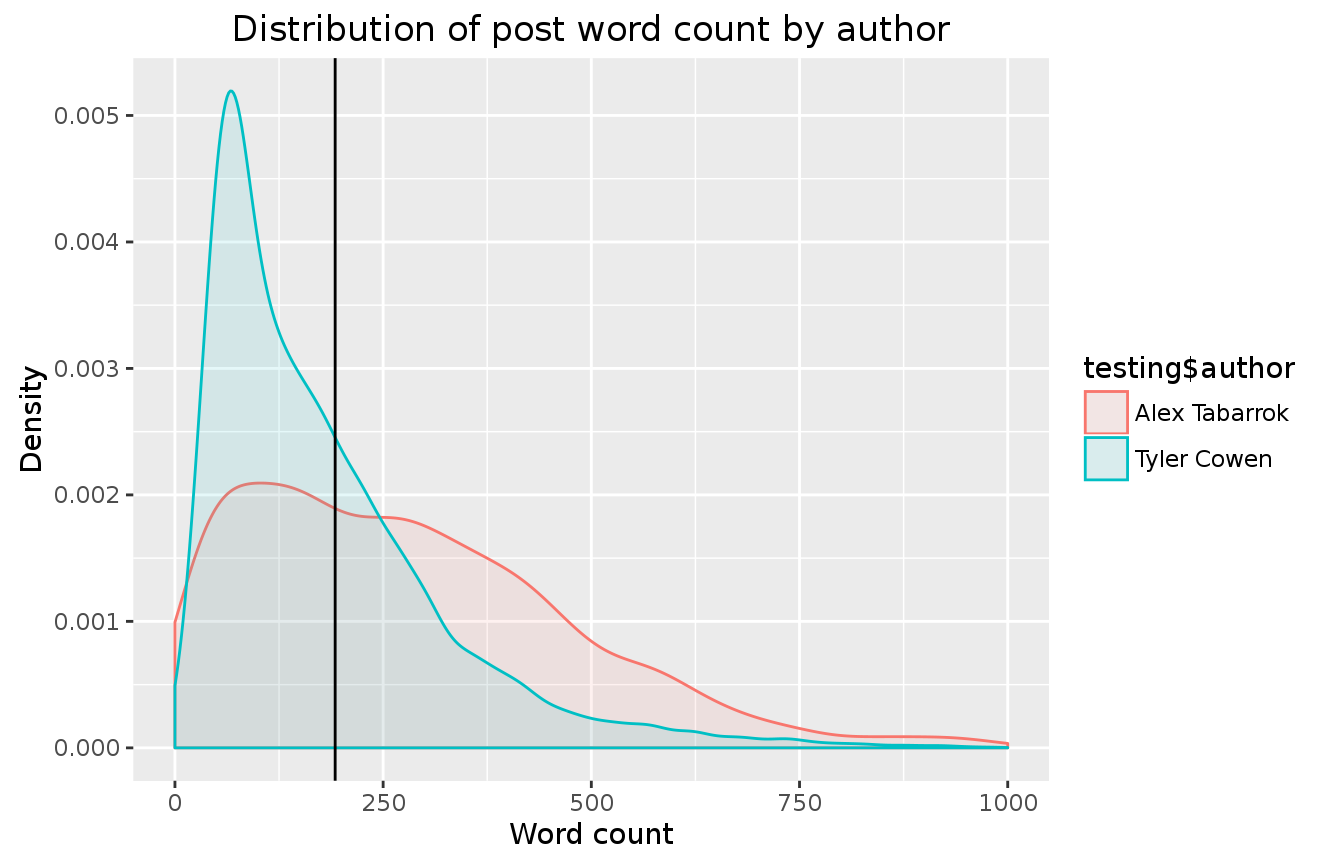

Toward a theory of Marginal Revolution, the blog

I found this pretty awesome and flattering (I couldn’t manage to indent it or get the formatting right):

Exploring the Marginal Revolution Dataset, by Will Nowak

1 Sept 2016

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Housekeeping

- 3 Exploratory Data Analysis

- 4 Comparative Plots

- 4.1 Hypothesis 1: Are posts getting longer (or shorter) over time?

- 4.2 Hypothesis 2: Do longer posts indicate more (or less) comments?

- 4.3 Hypothesis 3: Cowen contributes more often, but Tabbarok often has long posts. Does the data confirm?

- 4.4 Hypothesis 4: Cowen receives more comments, as he blogs more often and has more of a following:

- 5 Machine Learning

Once again, here is the link. There are excellent visuals and histograms, the programming is there too, and again that is from Will Nowak. And here is an updated version of blog content.

Anthony Goldbloom pointed me to this, and is involved in the larger project, and I thank also Erik Brynjolfsson for an introduction.

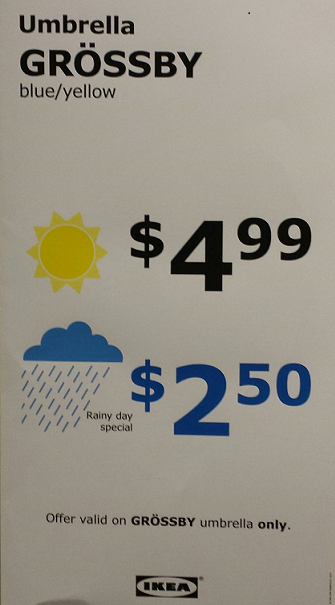

Anti-Surge Pricing

Charting Charts Chart

From Priceonomics which notes:

In our sample of Times pieces, we only found one chart used outside the Business section before 1990….By the late 2000s, charts had become central to the journalism at the Times. The newspaper had a team of graphics reporters infusing the paper with innovative visualizations. For the Times web edition, those data visualizations were often interactive.

…The New York Times cemented their prioritization of visual journalism when they launched the data-driven news site the Upshot in 2014. The Upshot’s original team of fifteen included three full-time graphic journalists.

Computers are the obvious driving factor. Data analysis and visualization are powerful tools. I would guess that data IQ has been increasing ala the Flynn effect.

How to boost employment

The Wi-Fi kiosks were designed to replace phone booths and allow users to consult maps, maybe check the weather or charge their phones. But they have also attracted people who linger for hours, sometimes drinking and doing drugs and, sometimes, boldly watching pornography on the sidewalks.

Now, yielding to complaints, the operators of the kiosks, LinkNYC network, are shutting off their internet browsers.

That is from Patrick McGheehan at the NYT.