Category: Economics

*The Failure of Judges and the Rise of Regulators*

That is the new book by Andrei Shleifer, and it collects his major and very important writings on regulation and law and economics, many with notable co-authors. Some of these papers have been discussed previously on MarginalRevolution. If you wish to own those papers, this is your book.

Questions that are rarely asked

From Arnold Kling (and the graph is from Karl Smith):

I challenge any supporter of the sticky-wage story (Bryan? Scott?) to write a 500-word essay explaining how this graph does not contradict their view. If employment fluctuations consisted of movements along an aggregate labor demand schedule, then employment should be at an all-time high right now.

My view is “sticky nominal wages for some, negative AD shock, ongoing stagnation and thus low job creation, and the progress we have is in some sectors immense but typically labor-saving rather than job-creating, all topped off with a liquidity shock-induced revelation that two percent of the previous work force was ZMP.” (Try screaming that from the rooftops.) I read the above graph as consistent with that mixed and moderate view. As Arnold notes, it’s harder to square with an AD-only view. If I wanted to push back a bit on Arnold’s take, and save some room for AD stories, I would cite the “Apple Fact of the Day,” and also note that stock prices have not responded nearly as well as have measured corporate profits. Still, we economists are not taking this graph seriously enough.

Addendum: Arnold Kling responds to responses.

Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit

The skills necessary to ride a bike are multifaceted, complex and not at all obvious or even easily explicable to the conscious mind. Once you learn, however, you never forget–that is the power of habit. Without the power of habit, we would be lost. Once a routine is programmed into system one (to use Kahneman’s terminology) we can accomplish great skills with astonishing ease. Our conscious mind, our system two, is not nearly fast enough or accurate enough to handle even what seems like a relatively simple task such as hitting a golf ball–which is why sports stars must learn to turn off system two, to practice “the art of not thinking,” in order to succeed.

Habits, however, can easily lead one into error. In the picture at right, which yellow line is longer? System one tells us that the l ine at the top is longer even though we all know that the lines are the same size. Measure once, measure twice, measure again and again and still the one at top looks longer at first glance. Now consider that this task is simple and system two knows with great certainty and conviction that the lines are the same and yet even so, it takes effort to overcome system one. Is it any wonder that we have much greater difficulty overcoming system one when the task is more complicated and system two less certain?

ine at the top is longer even though we all know that the lines are the same size. Measure once, measure twice, measure again and again and still the one at top looks longer at first glance. Now consider that this task is simple and system two knows with great certainty and conviction that the lines are the same and yet even so, it takes effort to overcome system one. Is it any wonder that we have much greater difficulty overcoming system one when the task is more complicated and system two less certain?

You never forget how to ride a bike. You also never forget how to eat, drink, or gamble–that is, you never forget the cues and rewards that boot up your behavioral routine, the habit loop. The habit loop is great when we need to reverse out of the driveway in the morning; cue the routine and let the zombie-within take over–we don’t even have to think about it–and we are out of the driveway in a flash. It’s not so great when we don’t want to eat the cookie on the counter–the cookie is seen, the routine is cued and the zombie-within gobbles it up–we don’t even have to think about it–oh sure, sometimes system two protests but heh what’s one cookie? And who is to say, maybe the line at the top is longer, it sure looks that way. Yum.

System two is at a distinct disadvantage and never more so when system one is backed by billions of dollars in advertising and research designed to encourage system one and armor it against the competition, skeptical system two. Yes, a company can make money selling rope to system two, but system one is the big spender.

Habits can never truly be broken but if one can recognize the cues and substitute different rewards to produce new routines, bad habits can be replaced with other, hopefully better habits. It’s habits all the way down but we have some choice about which habits bear the ego.

Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit, about which I am riffing off here, is all about habits and how they play out in the lives of people, organizations and cultures. I most enjoyed the opening and closing sections on the psychology of habits which can be read as a kind of user’s manual for managing your system one. The Power of Habit, following the Gladwellian style, also includes sections on the habits of corporations and groups (hello lucrative speaking gigs) some of these lost the main theme for me but the stories about Alcoa, Starbucks and the Civil Rights movement were still very good.

Duhigg is an excellent writer (he is the co-author of the recent investigative article on Apple, manufacturing and China that received so much attention) It will also not have escaped the reader’s attention that if a book about habits isn’t a great read then the author doesn’t know his material. Duhigg knows his material. The Power of Habit was hard to put down.

Austerity as a substitute for trust

Here is a common view, not incorrect as far as it goes:

Struggling euro-zone economies like Greece, Portugal, Spain and Italy cannot cut their way back to growth. Demanding rigid austerity from them as the price of European support has lengthened and deepened their recessions. It has made their debts harder, not easier, to pay off.

And here is a useful Paul Krugman post on austerity, perhaps the best single (brief) statement of his views on European austerity. Three observations:

1. I have yet to see a numerical analysis of European fiscal austerity which adjusts for a) falling ngdp, b) the collapse of their banking systems, c) and the collapse of M3 and money markets in some of these regions, noting that in Italy there are partial (very recent) signs of a money market turnaround. The blame gets pinned on the fiscal austerity.

2. I have yet to see a numerical analysis of European fiscal austerity which considers the prospect of later catch-up growth. This can make the costs of austerity much smaller, though of course from discount rates and habit formation there is still a cost.

3. Ideally it really would be better to say “Italy, I trust you to cut spending later, after your economy has recovered.” This cross-national trust is not present, least of all with Greece but also elsewhere. What is the best available policy in the absence of this trust, knowing that the periphery nations have to send some kind of credible signal to the wealthier nations of the North, in return for ongoing aid?

You can think of those three points as the “frontier reasons” why not all economists agree on European austerity. There are indeed some “dY/dG denialists,” but there are too many attacks on them and not enough explorations of the real issues.

Ironically, postponing austerity is most likely to succeed when there is lots of trust in a country (and in fact whether or not that trust is deserved). You can imagine the Swedes agreeing to themselves “we’ll cut spending three years from now” but the Greeks not, not without external constraint. Thus, writers who unmask the depravity of the American polity, and who polarize opinion, are oddly enough doing harm to the anti-austerity point of view.

You will find an alternative perspective on intellectual strategy here.

Why is there a shortage of talent in IT sectors and the like?

There have been some good posts on this lately, for instance asking why the wage simply doesn’t clear the market, why don’t firms train more workers, and so on (my apologies as I have lost track of those posts, so no links). The excellent Isaac Sorkin emails me with a link to this paper, Superstars and Mediocrities: Market Failures in the Discovery of Talent (pdf), by Marko Terviö, here is the abstract:

A basic problem facing most labor markets is that workers can neither commit to long-term wage contracts nor can they self fi nance the costs of production. I study the effects of these imperfections when talent is industry-specifi c, it can only be revealed on the job, and once learned becomes public information. I show that fi rms bid excessively for the pool of incumbent workers at the expense of trying out new talent. The workforce is then plagued with an unfavorable selection of individuals: there are too many mediocre workers, whose talent is not high enough to justify them crowding out novice workers with lower expected talent but with more upside potential. The result is an inefficiently low level of output coupled with higher wages for known high talents. This problem is most severe where information about talent is initially very imprecise and the complementary costs of production are high. I argue that high incomes in professions such as entertainment, management, and entrepreneurship, may be explained by the nature of the talent revelation process, rather than by an underlying scarcity of talent.

This result relates also to J.C.’s query about talent sorting, the signaling model of education, CEO pay, and many other results under recent discussion. If it matters to you, this paper was published in the Review of Economic Studies. I’m not sure that a theorist would consider this a “theory paper” but to me it is, and it is one of the most interesting theory papers I have seen in years.

Why doesn’t the right-wing favor looser monetary policy?

Reading Scott’s post induced me to write down these few points. I have noticed that right-wing public intellectuals are skeptical of more expansionary monetary policy for a few reasons:

1. There is a widespread belief that inflation helped cause the initial mess (not to mention centuries of other macroeconomic problems, plus the problems from the 1970s, plus the collapse of Zimbabwe), and that therefore inflation cannot be part of a preferred solution. It feels like a move in the wrong direction, and like an affiliation with ideas that are dangerous. I recall being fourteen years of age, being lectured about Andrew Dickson White’s work on assignats in Revolutionary France, and being bored because I already had heard the story.

2. There is a widespread belief that we have beat a lot of problems by “getting tough” with them. Reagan got tough with the Soviet Union, soon enough we need to get tough with government spending, and perhaps therefore we also need to be “tough on inflation.” The “turning on the spigot” metaphor feels like a move in the wrong direction. Tough guys turn off spigots.

3. There is a widespread belief that central bank discretion always will be abused (by no means is this view totally implausible). “Expansionary” monetary policy feels “more discretionary” than does “tight” monetary policy. Run those two words through your mind: “expansionary,” and “tight.” Which one sounds and feels more like “discretion”? To ask such a question is to answer it.

Within these frameworks of beliefs, expansionary monetary policy just doesn’t feel right. Yet I still agree with the arguments of Scott (and others) that it would have been the right thing to do.

What are the costs of signaling at a macro level?

There is a new paper from Ricardo Perez Truglia, from Harvard, on this topic. It strikes me as quite speculative, but nonetheless a step forward in addressing a very difficult question and adding some structure to the analysis of a very difficult problem. Here are his conclusions:

The goal of the paper is to provide a quantitative idea of the practical importance of conspicuous consumption. We estimated a signaling model using nationally representative data on consumption in the US, which we then use to estimate welfare implications and perform counterfactual analysis. We found that the market value of NMGs [TC: non market goods, as result from the signal] is non-negligible: for each dollar spent in clothing and cars the average household gets around 35 cents of net bene ts from NMGs. However, the large value of NMGs does not imply that the losses from the positional externality are also large. The results suggest that richer household would still consume relatively more of the NMG even in absence of NMGs, so the cost of the signal that they send is not very high. As a result, the signaling equilibrium attains almost 90% of the full potential bene ts from the NMGs, which is very e fficient. The unattained benefi ts, $32 per household per month, can serve as an intuitive upper bound to the bene fits that can be gained through economic policy, such as a tax on observable goods aimed at correcting the positional externality.

A related point is that if utility functions evolve so that people enjoy the very act of sending the signal, that too will lower the associated deadweight loss from signaling.

Here is the author’s home page.

J.C. Bradbury emails me on the allocation of talent

I hope you are doing well. I have a Micro III question that I thought might interest you. I often have such Tyler questions, but keep them to myself, yet this morning I decided to share with you.

What does Jeremy Lin tell us about talent evaluation mechanisms? This article ( http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2012/02/what-jeremy-lin-teaches-us-about-talent/?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=twitter ) argues that the standard benchmarks for evaluating basketball and football players at the draft level are flawed. The argument is that Jeremy Lin couldn’t get the opportunity to succeed because his skill wasn’t being picked up by the standard sorting procedure. This got me thinking. Baseball sorts players in a different way than basketball. In professional basketball (and football), college sports serve as minor leagues, where teams face a high variance in competition (the difference between the best and worst teams in a top conference is normally quite large), with very little room for promotion. There is some transferring as players succeed and fail at lower and higher levels, but for the most part you sink or swim at your initial college. This is compounded by the fact that the initial allocation of players to college teams is governed by a non-pecuniary rewards structure with a stringent wage ceiling, which likely hinders the allocation of talent. At the end of your college career, NBA teams make virtually all-or-nothing calls on a few players to fill vacancies at the major-league level. In baseball it’s different. Players play their way up the ladder, and even players who are undrafted can play their way onto teams at low levels of the minor league. At such low levels, the high variance in talent is high like it is in college sports; however, promotions from short-season leagues through Triple-A, allow incremental testing of talent along the way without much risk. I have looked at metrics for predicting major-league success from minor-league performance and found that it is not until you reach the High-A level (that is three steps below the majors) can performance tell you anything. Players in High-A who are on-track for the majors are about-the age of college seniors. Performance statistics from Low-A and below have no predictive power. Baseball is also much less of a team game than basketball, so this should make evaluation easier in baseball but it is still quite difficult by the time most players would be finishing college careers. Also, a baseball scout acquaintance, who is very well versed in statistics, tells me that standard baseball performance metrics in college games are virtually useless predictors of performance (this is contrary to an argument made in Moneyball). Even successful college baseball players almost always have to play their way onto the team.

Back to Lin. He played in the Ivy League and his stats weren’t all that bad or impressive in an environment that is far below the NBA. If Lin is a legitimate NBA player, he didn’t have many opportunities to play his way up like a baseball player does. In the NBA, he experienced drastic team switches, and even when making a team he received limited opportunities to play. MLB teams often keep superior talent in the minors so that they can get practice and be evaluated through in-game competition. An important sorting mechanism for labor market sorting is real-time work. Regardless of your school pedigree, most prestige professions (lawyers, financial managers, professors, etc.) have up-or-out rules after a period of probationary employment where skill is evaluated in real world action. Yes, there is a D-League and European basketball, but the D-league is not as developed as baseball’s minor-league system, and European basketball has high entry cost and may suffer from the same evaluation problems faced by the NBA. Thus, I wonder if the de facto college minor-league systems of basketball and football hinder the sorting of talent so that the Jeremy Lins and Kurt Warners of the world often don’t survive. Thus, another downside of these college sports monopsonies is an inferior allocation of talent at the next level.

J.C.’s points of course apply (with modifications) to economics, to economies, and to our understanding of meritocracy, not to mention to how books, movies, and music fare in the marketplace. Overall I would prefer to see economics devote much more attention to the topic of the allocation of talent.

Here is J.C. on Twitter, here are his books.

A wee bit of financial history

If March 4, 1933, and February 11, 2009, marked the nadirs of public confidence in Wall Street, then the years 1928 and 1999 marked the zeniths, when Goldman Sachs sold shares to the public for the only two times in its history. In December 1928, the partners of Goldman Sachs sold shares in a subsidiary called Goldman Sachs Trading Corporation–for its day, a complex, highly leveraged instrument with many layers that made transparency all but impossible. By the time of Roosevelt’s inauguration in 1933, the shares were nearly worthless. For the next 70 years, burned by that experience and FDR’s excoriation in 1933, the firm’s partners retreated to their roots as a private partnership, using their own personal capital with only modest leverage to advance their role as a financial intermediary.

By 1999, Goldman’s reputation had recovered to its previous zenith–to the point that a public offering again was possible. Its partners had debated the merits of such a change for years, and, even when the decision was made to go forward, the decision was reached only after vigorous debate and much disagreement. In favor of going public were those partners who saw a need for a larger capital base to allow the firm to compete in the increasingly globalized economy with the larger players both in the U.S. and overseas. Furthermore, once a public market was established for its shares, Goldman would have a currency other than cash with which to acquire other businesses and grow into financial services it could not afford to enter as a private partnership. On the other side of the argument were those partners who were worried about the impact that transition to a public firm would have on the firm’s culture. Heretofore, the firm had been known for its low ego and gang-tackling ethos, with aggressive personalities kept in check by the partnership potential that was strongly linked to both productivity and cultural fit.

What neither the firm’s partners nor outside observers were able to foresee was the resulting change in the firm’s risk tolerance…

For the pointer I thank John Phillips.

Scott Winship summary on mobility and inequality

Read it here, excerpt:

…evidence on earnings mobility in the sense of where parents and children rank suggests that our uniqueness lies in how ineffective we are at lifting up men who were poor as children. In other words, we have no more downward mobility from the middle than other nations, no less upward mobility from the middle, and no less downward mobility from the top. Nor do we have less upward mobility from the bottom among women. Only in terms of low upward mobility from the bottom among men does the U.S. stand out.

Not from Atlas Shrugged

The Hill: Six House Democrats, led by Rep. Dennis Kucinich (D-Ohio), want to set up a “Reasonable Profits Board” to control gas profits.

The Democrats, worried about higher gas prices, want to set up a board that would apply a “windfall profit tax” as high as 100 percent on the sale of oil and gas, according to their legislation.

…The Gas Price Spike Act, H.R. 3784, would apply a windfall tax on the sale of oil and gas that ranges from 50 percent to 100 percent on all surplus earnings exceeding “a reasonable profit.” It would set up a Reasonable Profits Board made up of three presidential nominees that will serve three-year terms.

And here directly from the proposed bill:

(4) REASONABLE PROFIT.—The term ‘reasonable profit’ means the amount determined by the Reasonable Profits Board to be a reasonable profit on the sale.

Addendum: Here is Bryan Caplan’s classic, Atlas Shrugged and Public Choice: The Obvious Parallels and here is the award-winning Atlas Shrugged app.

The economics of higher non-profit and for-profit education

Here is a 2009 paper of mine with Sam Papenfuss (pdf), a later version of which was published in this book edited by Joshua Hall. The paper deliberately sidesteps the recent scandals and focuses on fundamentalist explanations of why higher education might be provided on a non-profit or for-profit basis.

The key stylized facts are this:

Two primary features characterize the observed educational for-profits. First, for-profits tend to specialize in highly practical or vocational forms of training. For-profits are especially prominent in areas where student performance can be measured by a relatively objective, standardized test. Nonprofits, in contrast, have a stronger presence in the liberal arts, although they are by no means restricted to that arena..

This is a general pattern, and not unique to the United States today:

A comparison of for-profit and non-profit institutions in the Philippines [in the 1970s] bears out many of the differences noted above. Filipino for-profits tend to charge lower fees, specialize in education of lower academic reputation, spend less on capital equipment, and serve students who plan on pursuing vocational careers or taking a standardized vocational test upon graduation…Students at for-profits are approximately ten times more likely to take the tests. Adjusting for the lower pass rate from for-profits, the for-profits are putting about five times the number of students through the tests as the non-profits, even though for-profits educated no more than three-fifths of all Filipino students at the time.

Here is one possible (partial) resolution:

Faculty governance implies that for-profits and nonprofits place different relative weight on reputation and profits. The for-profit selects students and faculty on the basis of how easily their reputational benefits can be captured by shareholders, whereas the non-profit places greater weight on the reputational benefits that are kept by faculty. The for-profit pursues “reputation as valued by students in dollar terms” and the nonprofit pursues “reputation with the external world,” or “reputation as a public good.” In the resulting equilibrium, for-profits achieve lower status.

…The hypothesis therefore predicts a segmented market for higher education. Students who seek the highest levels of certification and reputation will attend non-profit institutions, which are run by faculty and use their prestige to raise donations. Students whose quality can be certified by an outside vocational exam do not need the non-profit reputational endorsement. They will pursue the more efficient instruction offered by for-profits.

There is a good recent paper by David Deming, Claudia Goldin, and Lawrence F. Katz on educational for-profits, available here. Here is a 2010 Dick Vedder piece on for-profits, more positive than most recent accounts.

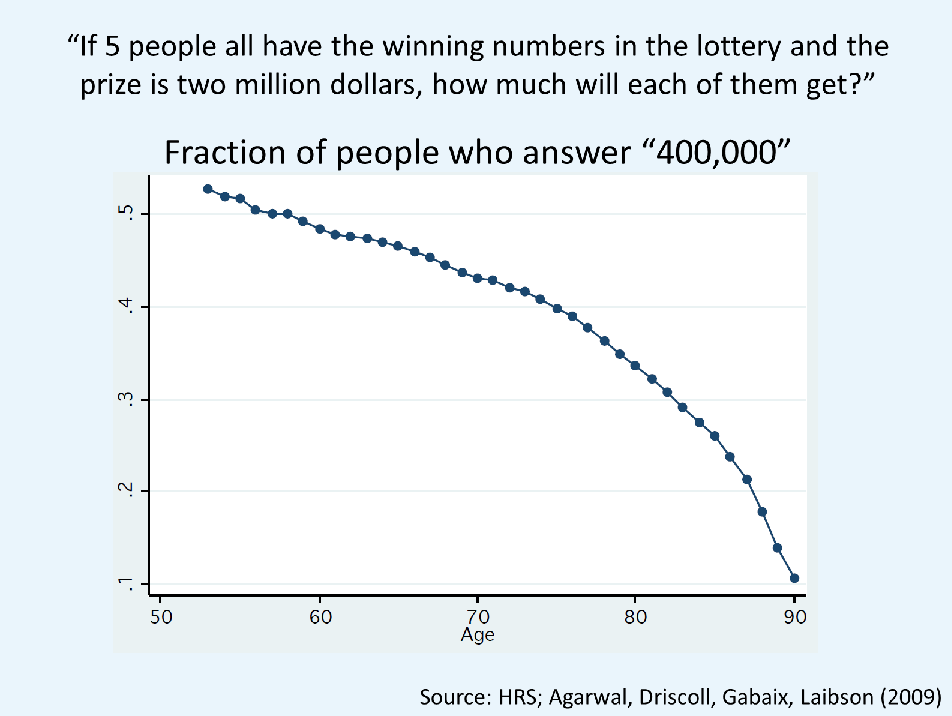

The Age of Reason

I don’t know which is scarier the height of the curve around age 50 or the slope of the curve (fyi, my guess is cohort effects are small). The slide is from David Laibson who has much more on aging and dementia; also raises issues of the value of medical care that maintains the body but not the mind.

Sentences to ponder

…when Prime Minister Mario Monti remarked that having a job for life in today’s economy was no longer feasible for young people — indeed, it was “monotonous” — he set off a barrage of protests, laying bare one of the sacrosanct tenets of Italian society that the euro zone crisis has placed at risk.

Reaction was fast, furious, bipartisan and intergenerational. “I think the prime minister has to be careful with the words he uses because people are a little angry,” Claudia Vori, a 31-year-old Rome native who has had 18 different jobs since graduating from high school in 1999…

This point is not irrelevant:

Debate has been especially intense over Article 18 of the 1970 Workers Statute, which forbids companies with more that 15 employees from firing people without just cause. The unions say that line cannot be crossed.

The article is here. How many years does it take to a) undo this, and b) have it kick in as a positive for growth? This again also gets back to the question of why Germany does not wish to pay for everything. By the way, is anyone writing a behavioral economics piece about how “crisis fatigue” increasingly is shaping eurozone policy?

Life as a pure rent-seeker? Or as the ultimate Kirznerian entrepreneur?

Or both. Gary Bemsel has visual acuity:

He can scan hundreds of video slots a minute, with an eagle eye honed by the past 15 years making his living as a racetrack stooper — someone who bends down to gather betting slips off the track floor in the hope of finding a mistakenly discarded winner.

…“It’s a legitimate living — the money’s been left behind,” he said on Wednesday. “It’s surer money than stooping; it’s steadier, and it’s cleaner — you don’t have to fish through garbage cans.”

Mr. Bemsel has not given up stooping. After a loop through the racino, he has enough cash to hit the betting window in the track and then scour the floor and trash for winning tickets. Slipping deftly through crowds of cheering and swearing horseplayers, he can read slips on the ground and tell immediately if they are winners. For face-down slips, he has developed a nimble, soccer-style flip move using both feet — so he barely has to stoop at all.

Yet returns are down:

“The first few weeks you could hit the A.T.M. machines for stray $20 bills lodged up in the dispenser,” Mr. Bemsel said. “But certain guys caught onto it, and now they stake out a machine all day, snatching them up.”

Nor has it worked out entirely well for him:

He works 12-hour days and finds $600 to $1,200 a week, Mr. Bemsel said, but winds up blowing most of it on bad horse picks. “The whole reason I do this is to feed my gambling addiction,” he said. “It’s an illness.”

The excellent article is here, and for the pointer I thank Ben Greenfield.