Category: Economics

Health Care Spending Growth Has Slowed: Will the Bend in the Curve Continue?

In large part yes:

Over 2009-2019 the seemingly inexorable rise in health care’s share of GDP markedly slowed, both in the US and elsewhere. To address whether this slowdown represents a reduced steadystate growth rate or just a temporary pause we specify and estimate a decomposition of health care spending growth. The post-2009 slowdown was importantly influenced by four factors. Population aging increased health care’s share of GDP, but three other factors more than offset the effect of aging: a temporary income effect stemming from the Great Recession; slowing relative medical price inflation; and a possibly longer lasting slowdown in the nature of technological change to increase the rate of cost-saving innovation. Looking forward, the

post-2009 moderation in the role of technological change as a driver of growth, if sustained, implies a reduction of 0.8 percentage points in health care spending growth; a sizeable decline in the context of the 2.0 percentage point differential in growth between health care spending and GDP in the 1970 to 2019 period.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Sheila D. Smith, Joseph P. Newhouse, and Gigi A. Cuckler.

The Birx Plan for Early Vaccination of the Nursing Homes

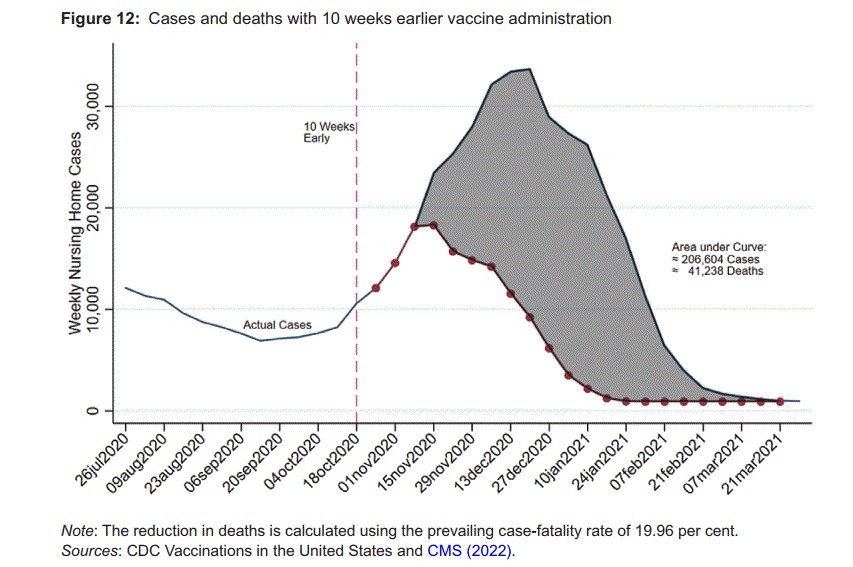

In Covid in the nursing homes: the US experience, Markus Bjoerkheim and I show that the Great Barrington “focused protection” plan was unlikely to have worked. I covered this last week. But there was one strategy which could have saved tens of thousands of lives–early vaccination. If the vaccine trials had been completed just 5 weeks earlier, for example, we could have saved 14 thousand lives in the nursing homes alone. But put aside the possibility of completing the trials earlier. There was another realistic possibility under our noses. We had could have offered nursing home residents the vaccine on a compassionate use basis, i.e. even before all the clinical trials were completed. An early vaccination option was neither unprecedented nor a question of 20-20 hindsight, early vaccination was discussed at the time:

Deborah Birx, the coordinator of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, forcefully advocated that nursing home residents should be given the option of being vaccinated earlier under a compassionate use authorization (Borrell, 2022). Many other treatments, such as convalescent plasma, were authorized under compassionate use procedures and there was more than enough vaccine available to vaccinate all nursing home residents. As a first approximation we find the Birx plan would have prevented in the order of 200,000 nursing home cases and 40,000 nursing home deaths. To put that in perspective, it amounts to reducing overall nursing home Covid deaths by over 26 per cent (using all CMS reported resident nursing home deaths as of 5 December 2021, and estimates of underreported deaths from Shen et al. (2021)).

The lesson is not primarily about the past. It’s about the central importance of vaccines in any plan to protect the vulnerable and about how we should be bolder and braver the next time.

Addendum: See also Tyler’s tremendous post (further below) on focused protection.

Liberal Democracy Strong

Bravo to Richard Hanania for revisiting some beliefs:

In February, I argued that Russia’s imminent successful invasion of Ukraine was a sign heralding in a new era of multipolarity. By October, I declared every challenge to liberal democracy dead and Fukuyama the prophet of our time. It’s embarrassing to have two contradictory pieces written seven months apart. But it would’ve been more embarrassing to persist in believing false things. If there’s any time to change one’s mind, it’s in the aftermath of large, historical events that went in ways you didn’t expect. Russia’s failure in Ukraine and China’s Zero Covid insanity provided extremely clear and vivid demonstrations of what democratic triumphalists have been saying about the flaws of autocracy. Nothing that the US or Europe have done – from the Iraq War to our own overly hysterical response to the coronavirus – have been in the same ballpark as these Chinese and Russian mistakes. Perhaps the war on terror comes close in terms of total destruction and lives lost, but we could afford to be stupid and it didn’t end up hurting Americans all that much.

In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king but still it’s good to see liberal democracy put some points on the scoreboard.

Why The United States Should Open New Consulates in India

A good piece by Michael Rubin in the National Interest:

India will likely become the most populous country on Earth this year, and, yet, outside of the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, there are only four State Department consulates in the country of 1.4 billion. That is fewer consulates than the State Department operates in France and fewer offices than the U.S. Embassy services in Spain. The Canadian province of Quebec, whose population totals less than nine million, merits two consulates in the State Department’s view.

…The United States computer and tech industry rests disproportionately on the labor and intellectual contributions of America’s vast Indian-American community. If Silicon Valley is the center of America’s computer industry, then Bangalore is its equivalent in India. The interaction between the two is significant. And yet, while India maintains a consulate in San Francisco, the United States has no equivalent in Bangalore; the closest American post is more than 200 miles away in Chennai. It need not be an either/or decision, but at the very least the State Department should explain why maintaining an investment in Winnipeg, Canada is more important than nurturing the relationship between two of the largest tech hubs in the world.

… if U.S. diplomacy is to be effective, it needs to adjust to twenty-first-century realities rather than nineteenth-century ones.

With more consulates might we not also cut the ridiculous and embarrassing time it takes to get a US visitor or business visa? When I was last in Delhi I met with one of the economic officers at the American Embassy. His job was to drum up business between India and the US–how can anyone do that when business visas are so difficult to acquire? Talk about the land of red tape!

Hat tip: Ben.

Why a four percent inflation target is a bad idea

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, let us start with part of the case for higher inflation:

A second argument, not usually cited by proponents, is that a higher inflation rate would lower the value of tenure, not just in academia but in bureaucracies more generally. Consider the unproductive employee who continues to work because his employers are afraid to fire him for legal or institutional reasons. With a higher rate of inflation, they could reduce his real wages simply by not giving him a raise, and that might even be enough to induce him to leave. In the meantime, they could redistribute higher wages toward more productive workers.

And yet:

But this second argument for higher inflation also hints at some reasons why a higher inflation target might prove problematic. Most notably, actual wages paid in the workplace do not rise automatically with the inflation rate. In economic theory, money is “neutral” in the long run; wages eventually adjust to the new level of prices. But this doesn’t just happen. Workers have to approach their bosses, ask for raises, bargain and, in some cases, threaten to leave.

t can be debated how smoothly this process runs in normal times. These are not normal times. This is an era of falling labor force participation, and there is talk of an epidemic of “quiet quitting.”

In other words, a lot of workers may not be too happy with their situation. There remains a risk that these workers, in lieu of bargaining for higher wages, will quit the labor force entirely, or perhaps just further disengage from their jobs. There are many margins across which the labor force can adjust.

Higher inflation rates are better for workers in some very particular environments. When the economic rate of growth is high and people are switching jobs at a rapid pace, productive workers will receive raises on a fairly frequent basis. A better job usually brings a higher wage, plus high turnover means employers are very conscious of the risk that workers will leave. Many bosses will offer raises without any bargaining at all.

Today, in contrast, there is a widespread labor shortage, as evidenced by the “Help Wanted” signs everywhere, yet there are also falling after-inflation wages.

We economists cannot fully explain these circumstances. But they may suggest that employers simply are not willing to agree to higher wages, perhaps due to business uncertainty. And if a labor shortage won’t push them to increase real wages, perhaps a higher rate of inflation won’t either.

In short, one of the main effects of a permanently higher inflation target may be lower real wages. It’s not a certainty that real wages would fall, but neither is it certain that, in the current climate, wages would keep pace. Why take the risk?

There is more at the link, including an additional argument why strict monetary neutrality may not hold (namely the four percent regime probably won’t be perceived as permanent).

Fires in San Francisco Lead to More Housing

Kate Pennington looks at the effect of new housing on rents and gentrification in San Francisco.

The clear identification challenge is that the timing and location of new construction are endogenous: developers are likely to build in the same areas that are already experiencing increased rents, displacement, and gentrification (Green et al., 2005; Li, 2019; Asquith et al., 2020).

Thus, she uses a clever identification strategy.

I exploit exogenous variation in the location of new construction caused by serious building fires. Regulation and geography combine to make San Francisco one of the most difficult places to build housing in the United States (Albouy and Ehrlich, 2012; Saiz, 2010). Serious fires, like the one shown in Figure 5, increase the probability of construction on the burned parcel by making it cheaper to build there. Removing incumbent tenants eliminates the need for costly buyouts. Under San Francisco just cause eviction law, landlords who want to sell or redevelop must either wait for tenants to voluntarily leave, or negotiate a buyout agreement to pay the tenant to leave. In 2015, the median buyout per tenant was $18,000 and the maximum was $325,000.19 Serious fires also streamline the permitting and construction process. Controlling for project size, construction on unburned parcels takes nearly a year longer to complete than projects on burned parcels (p=0.007).

I know what you cynical readers are thinking! Some fires are set on purpose to drive the tenants out! Well, that happens in the movies but it’s much rarer in real life when then there are very serious penalities for arson and homicide. In anycase, Pennington looks only at accidental fires, not arsons, and she finds that that the lots on which there were fires have similar rates of rental incrase and gentrification as other lots.

Amazingly, it still takes a long time to build on these burned lots–nearly five years to get a permit approved and 7.2 years before completion! Nevertheless, burned lots are much more likely to be redeveloped than similar unburned lots. The bottom line is that burned lots are a good as-if experiment for what would happen if a random set of lots were developed.

Pennington concludes that new housing has a “hyperlocal” increase in gentrification–basically richer people move into the new housing and there’s some very local increase in things like more up-scale restaurants–but overall rents are reduced and fewer people must move elsewhere to find cheaper housing.

I find that rents fall by 2% for parcels within 100m of new construction. Renters’ risk of displacement to a lower-income neighborhood falls by 17%. Both effects decay linearly to zero within 1.5km….Building more market rate housing benefits all San Francisco renters through spillover effects on rents.

Price behavior for new commodities (from my email)

You made a point in your podcast with Jeremy Grantham about the commodities market being relatively stable over the number of years that we can measure it, but I think when you refer to the commodities market, you’re talking about larger commodities, like copper and steel for which we have a much longer period of history.

In commodity markets some materials are relatively new. The history of markets for things like neodymium, dysprosium, and lithium is not long. These materials only recently became commodified enough that there was even such a thing as a market price.

These advanced refined materials may not fit our historical understanding due to: relative scarcity (geographic and in china, Dy, Nd mostly) specialized & region dependant extraction techniques; specificity in applications, (for example: i don’t know of any application for Dy other than high power magnets and wavelength specific lasers)

Consider that modern commodity markets in highly technological, relatively new, specific materials might not be subject to the same rules as historical commodity markets.

We haven’t seen an “advanced material commodity squeeze” yet, but I think we are due for one even bigger than the RE shock in 2011 (https://www.theguardian.com/business/2011/jun/19/rare-earth-minerals-china). So many technologies are based on a very fragile (geopolitical, economic) supply chain that we are bound to have a problem eventually.

Love the podcast & MR.

That is from Anonymous!

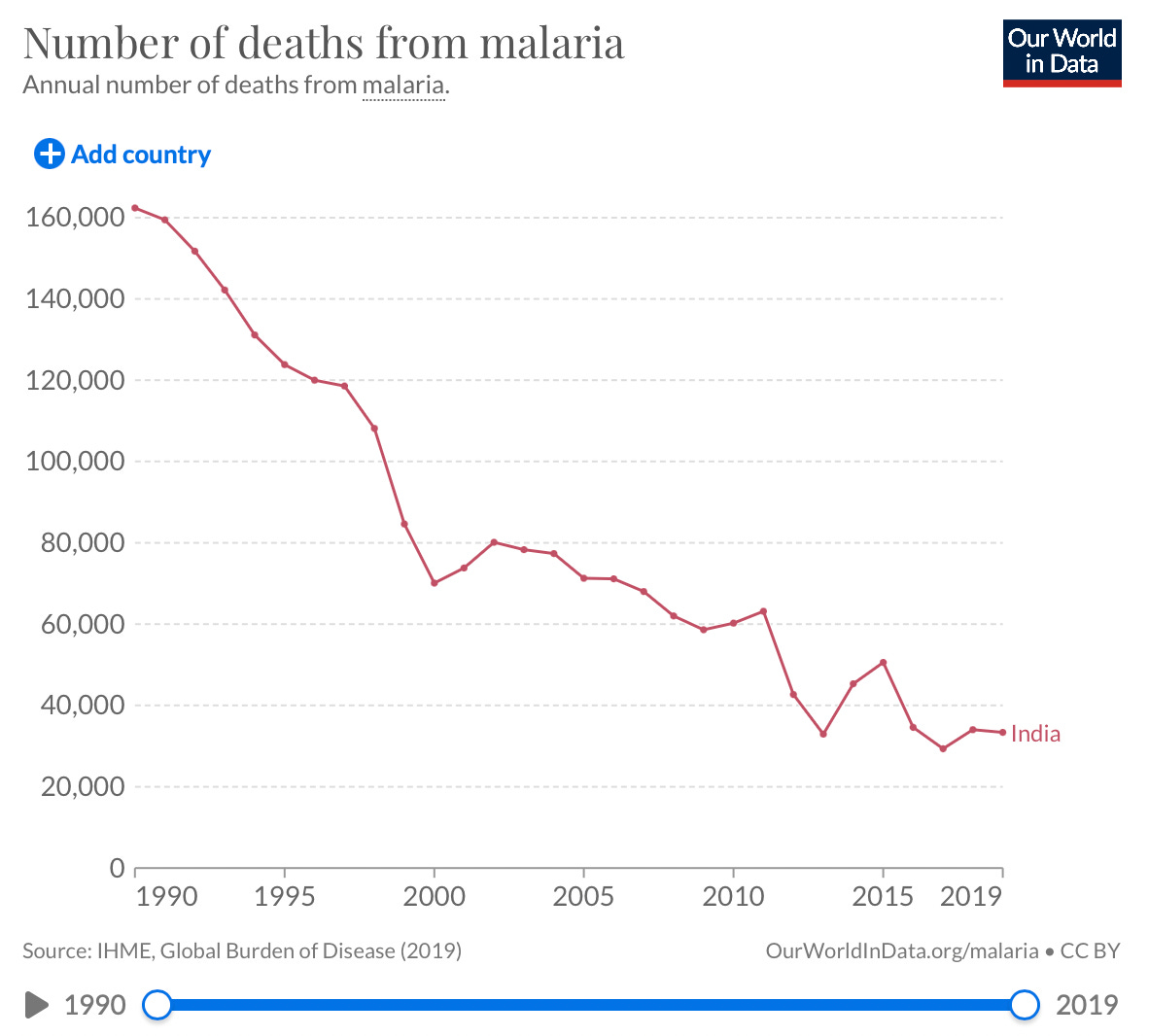

Shruti on Effective Altruism, malaria, India, and air pollution

Look at the decline in malaria deaths in India since the big bang reforms in 1991, which placed India on a higher growth trajectory averaging about 6 percent annual growth for almost three decades. Malaria deaths declined because Indians could afford better sanitation preventing illness and greater access to healthcare in case they contracted malaria. India did not witness a sudden surge in producing, importing or distributing mosquito nets. I grew up in India, in an area that is even today hit by dengue during the monsoon, but I have never seen the shortage of mosquito nets driving the surge in dengue patients. On the contrary, a surge in cases is caused by the municipal government allowing water logging and not maintaining appropriate levels of public sanitation. Or because of overcrowded hospitals that cannot save the lives of dengue patients in time.

There is much more at the link, from Shruti’s new Substack.

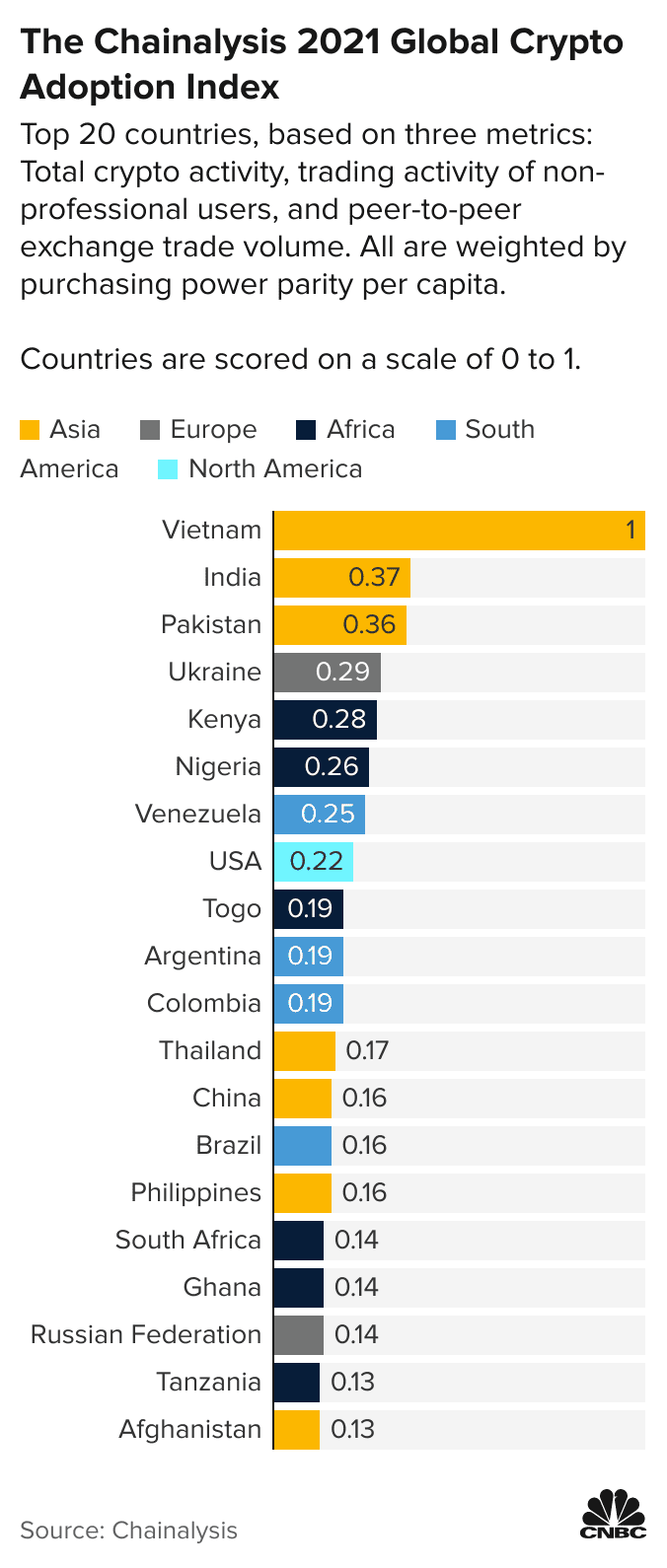

Why Scott Alexander does not hate crypto

Vietnam uses crypto because it’s terrible at banks. 69% of Vietnamese have no bank access, the second highest in the world. I’m not sure why; articles play up rural poverty, but many nations have more rural poor than Vietnam. There’s a history of the government forcing banks to make terrible loans, and then those banks collapsing; maybe this destroyed public trust? In any case, between banklessness and remittances (eg from Vietnamese-Americans), Vietnam leads the world in crypto use.

Ukraine has always been among the top crypto countries: in 2021, NYT called it “the crypto capital of the world”. Again, this owes a lot to its terrible banking system. NYT describes its banks as “so sclerotic that sending or receiving even small amounts of money from another country requires an exasperating obstacle course of paperwork”, and this guy says that if you deposit more than $100,000 in a Ukrainian bank, “the chance that you get it back is very slim”. When Russia invaded, the Ukrainian government doubled down on crypto as a way for friendly Westerners to send donations to support the war effort – $70 million as of March. It proved so helpful that during the first month of the war, in between dodging Russian artillery shells President Zelenskyy found time to pass a law legalizing crypto and strengthening its regulatory framework.

Venezuela’s economy has been in slow motion collapse for the past decade. The inflation is currently in the triple digits (remember, people thought the Democrats would lose the midterms because of a US inflation rate of 8%). If your country has a triple-digit inflation rate, you might prefer to use an alternative currency, which Venezuela’s authoritarian government tries to prevent people from doing. Cryptocurrency provides a hard-to-ban alternative which has caught on among Venezuelan hustlers and small businessmen.

And consider this picture:

Here is the full post.

The Story of VaccinateCA

The excellent Patrick McKenzie tells the story of VaccineCA, the ragtag group of volunteers that quickly became Google’s and then the US Government’s best source on where to find vaccines during the pandemic.

Wait. The US Government was giving out the vaccines. How could they not know where the vaccines were? It’s complicated. Operation Warp Speed delivered the vaccines to the pharmacy programs and to the states but after that they dissappeared into a morass of incompatible systems.

[L]et’s oversimplify: Vials were allocated by the federal government to states, which allocated them to counties, which allocated them to healthcare providers and community groups. The allocators of vials within each supply chain had sharply limited ability to see true systemic supply levels. The recipients of the vials in many cases had limited organizational ability to communicate to potential patients that they actually had them available.

Patients then asked the federal government, states, counties, healthcare providers and community groups, ‘Do you have the vaccine?’ And in most cases the only answer available to the person who picked up the phone was ‘I don’t have it. I don’t know if we have it. Plausibly someone has it. Maybe you should call someone else.’ Technologists will see the analogy to a distributed denial of service incident, and as if the overwhelming demand was not enough of a problem, the rerouting of calls between institutions amplified the burden on the healthcare system. Vaccine seekers were routinely making dozens of calls.

This caused a standing wave of inquiries to hit all levels of US healthcare infrastructure in the early months of the vaccination effort. Very few of those inquiries went well for any party. It is widely believed, and was widely believed at the time, that this was primarily because supply was lacking, but it was often the case that supply was frequently not being used as quickly as it was produced because demand could not find it.

It turned out that the best way to get visibility into this mess was not to trace the vaccines but to call the endpoints on the phone and then create a database that people could access which is what VaccinateCA did but in addition to finding the doses they had to deal with the issue of who was allowed access.

A key consideration for us, from the first day of the effort, was recording not just which pharmacist had vials but who they thought they could provide care to. This was dependent on prevailing regulations in their state and county, interpretations of those regulations by the pharmacy chain, and (frequently!) ad hoc decision-making by individual medical providers. Individual providers routinely made decisions that the relevant policy makers did not agree comported with their understanding of the rules.

VaccinateCA saw the policy sausage made in real time in California while keeping an eye on it nationwide. It continues to give me nightmares.

California, not to mince words, prioritized the appearance of equity over saving lives, over and over and over again, as part of an explicitly documented strategy, at all levels of the government. You can read the sanitized version of the rationale, by putative medical ethics experts, in numerous official documents. The less sanitized version came out frequently in meetings.

This was the official strategy.

The unofficial strategy, the result the system actually obtained, was that early access to the vaccine was preferentially awarded based on proximity to power and to the professional-managerial class.

… The essential workers list heavily informed the vaccination prioritization schedule. Lobbyists used it as procedural leverage to prioritize their clients for vaccines. The veterinary lobby was unusually candid, in writing, about how it achieved maximum priority (1A) for veterinarians due to them being ‘healthcare workers’.

Teachers’ unions worked tirelessly and landed teachers a 1B. They were ahead of 1C, which included (among others) non-elderly people for whom preexisting severe disability meant that ‘a covid-19 infection is likely to result in severe life-threatening illness or death’. The public rationale was that teachers were at elevated risk of exposure through their occupation. Schools were, of course, mostly closed at the time, and teachers were Zooming along with the rest of the professional-managerial class, but teachers’ unions have power and so 1B it was. Young, healthy teachers quarantining at home were offered the vaccine before people who doctors thought would probably die if they caught Covid.

Now repeat this exercise up and down the social structure and economy of the United States.

…Healthcare providers were fired for administering doses that were destined to expire uselessly. The public health sector devoted substantial attention to the problem of vaccinating too many people during a pandemic. Administration of the formal spoils system became farcically complicated and frequently outcompeted administration of the vaccine as a goal.

The process of registering for the vaccine inherited the complexity of the negotiation over the prioritization, and so vulnerable people were asked to parse rules that routinely befuddled healthy professional software engineers and healthcare administrators – the state of New York subjected senior citizens to a ‘51 step online questionnaire that include[d] uploading multiple attachments’!

That isn’t hyperbole! New York meant to do that! On purpose!

Lives were sacrificed by the thousands and tens of thousands for political reasons. Many more were lost because institutions failed to execute with the competence and vigor the United States is abundantly capable of.

…The State of California instituted a policy of redlining in the provision of medical care in a pandemic to thunderous applause from its activist class and medical ethics experts….Residency restrictions were pervasively enforced at the county level and frequently finer-grained than that. A pop-up clinic, for example, might have been restricted to residents of a single zip code or small group of zip codes.

All people are equal in the eyes of the law in California, but some people are . . . let’s politely say ‘administratively disfavored’.

The theory was, and you could write down this part of it, disfavored potential patients might use social advantages like better access to information and transportation to present themselves for treatment at locations that had doses allocated for favored potential patients. This part of the theory was extremely well-founded. Many people were willing to drive the length and breadth of California for their dose and did so.

What many wanted to do, and this is the part that they couldn’t write down, is deny healthcare to disfavored patients. Since healthcare providers are public accommodations in the state of California, they are legally forbidden from discriminating on the basis of characteristics that some people wanted to discriminate on. So that was laundered through residency restrictions.

Many more items of interest. I didn’t know this incredibly fact about the Biden adminsitratins Vaccines.gov for example:

Pharmacies through the FRPP had roughly half of the doses; states and counties had roughly the other half (sometimes administered at pharmacies, because clearly this isn’t complicated enough yet). You would hope that state and county doses were findable on Vaccines.gov. It was going to be the centerpiece of the Biden administration’s effort to fix the vaccine finding problem and take credit for doing so.

…Since the optics would be terrible if America appeared to serve some states much better than others on the official website that everyone would assume must show all the doses, no state doses, not even from states that would opt in, would be shown on it, at least not at the moment of maximum publicity. Got that?

A good point about America.

We also benefited from another major strength of America: You cannot get arrested, jailed, or shot for publishing true facts, even if those facts happen to embarrass people in positions of power. Many funders wanted us to expand the model to a particular nation. In early talks with contacts there in civil society, it was explained repeatedly and at length that a local team that embarrassed the government’s vaccination rollout would be arrested and beaten by people carrying guns. This made it ethically challenging to take charitable donations and try to recruit that team.

Many more points of interest about the process of running a medical startup during a pandemic. Read the whole thing.

Chinese Industrial Policy is Failing

In Picking Winners? Government Subsidies and Firm Productivity in China, Branstetter, Li and Ren look at the effect of direct cash subsidies to Chinese firms.

Our results provide little evidence to support the view that government subsidies have been given to more productive firms or that they have enhanced the productivity of the Chinese listed firms. First, at the aggregate level, subsidies seem to be allocated to less productive firms, and the relative productivity of firms’ receiving these subsidies appears to decline further after disbursement. Second, using the categorized subsidy data, we find that neither subsidies promoting R&D and innovation promotion nor subsidies promoting industrial and equipment upgrading are positively associated with firms’ subsequent productivity growth. On the other hand, we find there is a positive association between subsidy and employment, both for aggregate and employment-related subsidies.

I appreciated this discussion of the earlier debate over Japanese industrial policy:

Drawing upon qualitative methods and largely anecdotal evidence, a group of noneconomists, business experts, and policymakers argued that Japan’s rapid recovery and robust growth after WWII could be explained by skillful industrial policy (Johnson, 1982; Prestowitz, 1988; Vogel, 1979) .10 Japan’s “government-led” economic model came to be viewed as a threat to U.S. prosperity by some participants in these debates. By the end of the 1980s, some policy makers and influential experts were calling for a policy of “containing Japan,” lest its unbalanced growth undermine the economy of the United States (Fallows, 1989).

Economists and more empirically minded social scientists in other disciplines viewed the claims of industrial policy efficacy with skepticism and suggested that Japan’s intervention in its economy tended to favor declining industries rather than growing ones (Calder, 1988; Saxonhouse, 1983).11 Eventually, the skeptics were able to bolster their claims with hard data demonstrating that the Japanese government had offered some degree of economic support to nearly all sectors, but that the preponderance of support had not gone to the sectors or firms with the fastest productivity growth. An important turning point in this debate came in the form of a careful econometric deconstruction of the notion that industrial policy drove Japan’s economic miracle published by Richard Beason and David Weinstein in the mid-1990s. This empirical analysis at the industry level found no relationship between productivity growth and the alleged instruments of industrial policy (Beason and Weinstein, 1996). As it turned out, the policy efforts to promote rising sectors championed by some elements of Japan’s bureaucracy were undermined by countervailing efforts to buttress the employment levels and solvency of politically connected but economically weak firms and industries.

Japan’s long period of economic outperformance came to an abrupt end in the early 1990s; after two decades of slow growth, few scholars now argue that Japanese industrial policy is a model worthy of emulation (Ito & Hoshi, 2020).

As I emphasized in my post, What Operation Warp Speed Did, Didn’t and Can’t Do, you need a lot more than “market failure” to have a successful government subsidy program of firms–you need massive externalities and precise, well understood targets. The garden-variety market failure that can be shown on a blackboard isn’t enough, in part because such arguments often underestimate the market and in part because they overestimate government.

Hat tip: Caleb Watney who offers some useful comments.

Is publication bias worse in economics?

Publication selection bias undermines the systematic accumulation of evidence. To assess the extent of this problem, we survey over 26,000 meta-analyses containing more than 800,000 effect size estimates from medicine, economics, and psychology. Our results indicate that meta-analyses in economics are the most severely contaminated by publication selection bias, closely followed by meta-analyses in psychology, whereas meta-analyses in medicine are contaminated the least. The median probability of the presence of an effect in economics decreased from 99.9% to 29.7% after adjusting for publication selection bias. This reduction was slightly lower in psychology (98.9% −→55.7%) and considerably lower in medicine (38.0% −→ 27.5%). The high prevalence of publication selection bias underscores the importance of adopting better research practices such as preregistration and registered reports.

Here is the full article by František Bartoš, et.al, via Paul Blossom.

Using Neural Networks to Predict Microspatial Economic Growth

We apply deep learning to daytime satellite imagery to predict changes in income and population at high spatial resolution in US data. For grid cells with lateral dimensions of 1.2 km and 2.4 km (where the average US county has dimension of 51.9 km), our model predictions achieve R2 values of 0.85 to 0.91 in levels, which far exceed the accuracy of existing models, and 0.32 to 0.46 in decadal changes, which have no counterpart in the literature and are 3–4 times larger than for commonly used nighttime lights. Our network has wide application for analyzing localized shocks.

Here is the AEA-gated published version, and here are other (mostly ungated) versions. Arman Khachiyan, Anthony Thomas, Huye Zhou, Gordon Hanson, Alex Cloninger, Tajana Rosing and Amit K. Khandelwal, and look for more papers to come in this area.

Productivity in the two Irelands (extrapolate this)

Of the 17 sectors for which we have comparable data, productivity levels in Ireland noticeably exceed those of Northern Ireland in 14 sectors, with particularly large gaps in Administrative and support services activities;

Financial and insurance activities; Legal and accounting activities etc; and Scientific research and development. Northern Ireland has an advantage in the two sectors of Electricity and gas supply and Construction.Productivity levels in the two regions were broadly equivalent in 2000. Over the period 2001 to 2020, productivity levels in Ireland have trended slightly upwards, while in Northern Ireland productivity levels have been trending downwards. By 2020, productivity per worker was approximately 40 per cent higher in Ireland compared to Northern Ireland.

That is from a new study by Adele Bergin and Seamus McGuinness, via Charles Klingman. Of the seventeen sectors for which there are comparable data: ” Northern Ireland has an advantage in the two sectors of Electricity and gas supply and Construction.” And from commentator David Jordan note this: “As the authors conclude, the failure of Northern Ireland’s economy to respond positively to increases in education, investment, and export intensity, suggests that other barriers to productivity growth exist.”

AFA mask meeting update

Dear AFA Member:

Given the vaccine requirement to register for the ASSA meetings, the AFA Board has decided to make mask-wearing optional at the AFA sessions held in the Sheraton Hotel in January 2023. We will respect each individual’s decision on whether to wear a mask. (Please note that you may still be required to wear a mask should you attend AEA sessions in the Hilton and other hotels.)

Sincerely,

The AFA Board of Directors

To be clear, that is AFA, not AEA, in other words the American Finance Association. AFA has followed the science, and the market signals, and seen the light. You would only have to change one little letter for the “AEA” to do the same…