Category: Economics

The overreaction to the Truss macro policy

It has been extreme:

I know an unpopular economic policy when I see one. And the consensus among economists about the tax cuts and deregulations announced last week by UK Prime Minister Liz Truss is almost universally negative. Larry Summers noted: “I think Britain will be remembered for having pursued the worst macroeconomic policies of any major country in a long time.” Willem Buiter described it as “totally, totally nuts.” Paul Krugman is skeptical. As Jason Furman summed it up: “I’ve rarely seen an economic policy that is as uniformly panned by economic experts and financial markets.”

That is from my latest Bloomberg column. I certainly can see reasons why one might oppose the plan, but the skies are not going to fall:

I see no evidence that the markets are beginning to doubt the UK’s ability to repay its debts. The UK, and earlier Great Britain, has arguably the best debt repayment history of all time (though it did default on some of its debts to Italian lenders in the 13th century). It even repaid its extensive debts from the Napoleonic Wars, though they were more than 200% of GDP.

There are different ways you might measure the marginal cost of UK government borrowing, but I don’t see any measure where it is high and under many measures it is negative in real terms. Remember when people used to tell us this meant there was no major problem on the fiscal side?

I do criticize the Bank of England for not doing more to reign in inflation, plus the government should have coordinated better with the Bank. And don’t forget this:

The Truss plan offers many admirable deregulations, including an attempt to get the UK economy to build more residential structures, as it so badly needs. It is difficult to say now just how successful this plan will be, but it is definitely a step in the right direction, as are most of the other deregulations, including lifting the ban on onshore wind generators. By calling the Truss plan the worst thing ever, commentators make it unlikely that these ideas will get the approbation they deserve.

Recommended.

From the comments, more on health care

Again this comment is from Sure:

The Truss economic plan

On Friday [as indeed it happened], Ms. Truss’ government is expected to announce a series of tax cuts, including cutting taxes for new home purchases as well as reversing planned hikes in the corporate tax and cutting a recent increase in payroll taxes. It will also abolish limits on bonuses for bankers and allow fracking for shale gas across the U.K.

The measures come in addition to a big government spending plan to cap household and corporate energy bills this winter that could cost the U.K. government roughly £100 billion, equivalent to about $113 billion, over the next two years.

The goal is to spur growth in an economy facing weak growth and high inflation, partly brought on by an energy price shock from higher natural-gas prices from the war in Ukraine, as well as a U.S.-style labor shortage. Absent the government bailouts, economists warned that many Britons would be unable to pay their energy bills this coming winter and thousands of companies would go broke…

The government is also planning a deregulation drive, in particular in the finance sector, to try to bolster London’s role as a business hub.

Taken together, the Truss plan is a bold but risky gamble that the payoff from higher growth will more than offset the risks from a big expansion in the government’s deficit and debt at a time of high inflation and rising interest rates, which will increase the cost of servicing the debt and could shake investors’ confidence in the U.K. economy and its currency.

Here is more from the WSJ. Elsewhere Ryan Bourne covers the tax changes in more detail:

-

- the recent 1.25 percent employer and employee national insurance tax rises have been reversed;

- the basic rate of income tax would be cut from 20 percent to 19 percent;

- the highest 45 percent marginal income tax rate would be abolished entirely, making 40 percent the top official marginal rate band;

- stamp duty (the property transactions tax) on all transactions up to home values of £250,000 and £425,000 for first-time buyers has been scrapped;

- the planned increase in the corporate profits tax has been abandoned (so maintaining it at 19 percent);

- full and immediate expensing in the corporate tax code for the first £1 million invested in plant and machinery would be made permanent;

- new investment zones would be introduced, in which there would be a 100 percent first year enhanced capital allowance relief for plant and machinery and building and structures relief of 20 percent per year.

And on regulation:

- new investment zones would encompass streamlining existing planning applications (and these are potentially big zones, if the councils and authorities in discussions are any guide – the Greater London Authority, for example);

- environmental reviews would be shortened and reformed;

- childcare deregulation proposals (probably on staffing and occupational licensing) are forthcoming;

- new planning reforms for housing are forthcoming;

- the onshore wind generator ban will be lifted;

- the fracking moratorium has been lifted;

- the cap on bankers’ bonuses will be abandoned;

- agricultural regulation will be reformed;

- the sugar tax and lots of other anti-obesity regulations will be abandoned;

- the arduous tax rules on contractors known as IR35 will be scrapped;

- all future tax policy will be reviewed through this prism of simplification;

-

there will be an expansion of the number of welfare claimants who must submit to more intensive work coaching with the aim of increasing their hours

The FT details the negative reaction from UK bond, equity, and currency markets. Furman and Buiter are very negative, Summers too. In my view, these are mostly good policies, but how will all that borrowing go over? And is the Bank of England up to doing the appropriate offsets? I will cover these policies as they unfold…

From the comments, on single payer

Single payer’s magic has historically worked via just a few channels:

1. Some amount of monopsony allows the government to bid down medical services below market rates.

2. Political imperatives lead to lower training burdens, lower staffing ratios, and lower certainty in diagnosis and treatment.

3. Obfuscation of possible alternatives diminishes demand for costlier care.Option 1 means that you pay health professionals worse. There is some utility in this even. But it has some long run consequences that are only now being discovered. First, you see the exit of the most skilled people from medical careers. Second, the physicians unionize (or equivalent) and become political actors. Third, with everyone trying this and some semblance of open borders, it becomes ever harder to keep people in the places you need them (which rarely match the places where the sort of folks who can become Western physicians want to live). At some point you can no longer suppress wages below their natural clearing rate and it becomes ever harder to import foreign talent when other places (e.g. the US) offer a more lucrative immigration option.

US physicians are overtrained. But it also means that as things need ever more understanding to manage, we can deal better with things like CAR-T therapy and the like. And it is not like foreign docs are unaware of these things. As status is the important thing for most educated professionals, there will be continuous pressure towards increasing the prestige of the job at that comes with more training. As much as the government wants to have the minimally trained folks doing as much as possible, single payer countries are starting to see ever more pressure for their physicians, nurses, and the rest to match educational qualifications of the rest of the world.

Tying into all of this is the fact that the alternatives are quite visible. Everyone in the US these days can see an alternative where the masses do not have to pay out of pocket and theoretically fund health care by taxing someone else. But the flip side is also true. Wealthy Britons know that their American friends need not live with chronic pain for years for surgeries the NHS eventually will perform. They know that their American friends get screened more frequently and actually get treatment that cures diseases which are merely managed in Britain. They may still support the tradeoffs that come from single payer, but the days when these sorts of comparisons are no longer discussed are long gone.

Frankly I am always amazed at how much gets attributed to single payer. We know that, at most, only 25% of life expectancy outcomes are due to healthcare. We know that all of the correlates of single payer (e.g. percent of health expenditures paid by government) and health correlates (e.g. life expectancy) get vastly less favorable when you drop the US from the analysis as an outlier. We know that the UK has habitually adopted US practices a decade or so later, once the cost falls into the range where the UK can afford it.

But going forward, I think the old metrics that showed large advantages for single payer are going to continue to slide. Unions (formal or otherwise) are going to militate for higher pay. Governments are going to have to deal with one side of the political spectrum going into hoc to the health employees and the other polarizing to the folks in the disfavored region(s) who are lower priority for healthcare and pay more in taxes for the “giveaways”. And all of it is going to run into the trouble that the developing world is going to have fewer kids and hence fewer physicians while the relative advantage of immigrating is going to continue to fall.

Single payer was overwhelmingly built on the post-World Wars consensus and environment. It operates as a monopsony. What on earth would make us think that it would be stable into the future?

That is from “Sure.”

TC again: There is a natural tendency on the internet to think that all universal coverage systems are single payer, but they are not. There is also a natural tendency to contrast single payer systems with freer market alternatives, but that is also an option not a necessity. You also can contrast single payer systems with mixed systems where both the government and the private sector have a major role, such as in Switzerland.

I’ll say it again: single payer systems just don’t have the resources or the capitalization to do well in the future, or for that matter the present. Populations are aging, Covid-related costs (including burdens on labor supply) have been a problem, income inequality pulls away medical personnel from government jobs, and health care costs have been rising around the world. Citizens will tolerate only so much taxation, plus mobility issues may bite. So the single payer systems just don’t have enough money to get the job done. That stance is conceptually distinct from thinking health care should be put on a much bigger market footing. But at the very least it will require a larger private sector role for the financing.

The Quantity Theory of Money is underrated

That is the theme of my latest Bloomberg column. Here is one short bit:

Consider the recent spurt of 8% to 9% inflation in the US. The simple fact is that M2 — one broad measure of the money supply — went up about 40% between February 2020 and February 2022. In the quantity theory approach, that would be reason to expect additional inflation, and of course that is exactly what happened.

The quantity theory has never held exactly, one reason being that the velocity (or rate of turnover) of money can vary as well. Early on in the pandemic, spending on many services was difficult or even dangerous, and so savings skyrocketed. Yet those days did not last, and when the new money supply increase was unleashed on the US economy, there were inflationary consequences.

I do think there are plenty of indeterminacies in macro, but letting M2 rise at such a pace is not one of them!

My Conversation with Byron Auguste

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is my introduction:

TYLER COWEN: Today I am here…with Byron Auguste, who is president and co-founder of Opportunity@Work, a civic enterprise which aims to improve the US labor market. Byron served for two years in the White House as deputy assistant to the president for economic policy and deputy director to the National Economic Council. Until 2013, he was senior partner at McKinsey and worked there for many years. He has also been an economist at LMC International, Oxford University, and the African Development Bank.

He is author of a 1995 book called The Economics of International Payments Unions and Clearing Houses. He has a doctorate of philosophy and economics from Oxford University, an undergraduate econ degree from Yale, and has been a Marshall Scholar. Welcome.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: As you know, more and more top universities are moving away from requiring standardized testing for people applying. Is this good or bad from your point of view?

AUGUSTE: I think it’s really too early to tell because the question is —

COWEN: But you want alternative markers, not just what kind of family you came from, what kind of prep you had. If you’re just smart, why shouldn’t we let you standardize test?

AUGUSTE: I think alternative markers are key. This is actually a pretty complicated issue, and I’ve talked to university administrators and admissions people, and it’s interesting, the variety of different ways they’re trying to work on this.

But I will say this. If you think about something like the SAT, when it first started — I’m talking about in the 1930s essentially — it was an alternative route into a college. It started with the Ivies. It was started with James Conant and Harvard and the Ivies and the Seven Sisters and the rest, and then it gradually moved out.

The problem they were trying to solve back in the ’30s was that up until that point, the way you got into, say, Dartmouth is the headmaster of Choate would write to Dartmouth and say, “Here’s our 15 candidates for Dartmouth.” Dartmouth would mostly take them because Choate knew what Dartmouth wanted. Then you had the high school movement in the US, where between 1909 and 1939, you went from 9 percent of American teenagers going to high school to 79 percent going to high school.

Now, suddenly, you had high school students applying to college. They were at Dubuque Normal School in Iowa. How does Dartmouth know whether this person was . . . The people from Choate didn’t start taking the SATs, but the SAT — even though it was a pretty terrible test at the time, it was better than nothing. It was a way that someone who was out there — not in the normal feeder schools — could distinguish themselves.

I think that is a very valuable role to play. As you know, Tyler, the SAT does, to some extent, still play that role. But also, because now that everybody has had to use it, it also is something that can be gamed more — test prep and all the rest of it.

COWEN: But it tracks IQ pretty closely. And a lot of Asian schools way overemphasize standard testing, I would say, and they’ve risen to very high levels of quality very quickly. It just seems like a good thing to do.

Most of all we cover jobs, training/retraining, and education. Interesting throughout.

Taxing Mechanical Engineers and Subsidizing Drama Majors

![]() In The Student Loan Giveaway is Much Bigger Than You Think I argued that the Biden student loan plan would incentivize students to take on more debt and incentivize schools to raise tuition with most of the increased costs being passed on to taxpayers through generous income based repayment plans. Adam Looney at Brookings takes a deep dive into the IDR plan and concludes that it’s even worse than I thought. Here are some of Looney’s key points:

In The Student Loan Giveaway is Much Bigger Than You Think I argued that the Biden student loan plan would incentivize students to take on more debt and incentivize schools to raise tuition with most of the increased costs being passed on to taxpayers through generous income based repayment plans. Adam Looney at Brookings takes a deep dive into the IDR plan and concludes that it’s even worse than I thought. Here are some of Looney’s key points:

- As recently as 2017, CBO projected that student loan borrowers would, on average, repay close to $1.11 per dollar they borrowed (including interest). Borrowing was often perceived to be the least favorable way to pay for college. But under the administration’s IDR proposal (and other regulatory changes), undergraduate borrowers who enroll in the plan might be expected to pay approximately $0.50 for each $1 borrowed—and some can reliably expect to pay zero. As a result, borrowing will be the best way to pay for college. If there’s a chance you’ll not need to repay all of the loan—and it’s likely that a majority of undergraduate students will be in that boat—it will be a financial no-brainer to take out the maximum student loan.

- The data shows that roughly half of Americans with some college experience but not a BA would qualify for zero payments under the proposal, as would about 25% of BA graduates. However, the vast majority of students (including more than 80% of BA recipients) would qualify for reduced payments.

- [A] lot of student debt represents borrowing for living expenses, and thus a sizable share of the value of loans forgiven under the IDR proposal will be for such expenses…A graduate student at Columbia University can borrow $30,827 each year for living expenses, personal expenses, and other costs above and beyond how much they borrow for tuition. A significant number of those graduates can expect those borrowed amounts to be forgiven. That means that the federal government will pay twice as much to subsidize the rent of a Columbia graduate student than it will for a low-income individual under the Section 8 housing voucher program…

Looney agrees that the incentive to increase tuition will apply to some graduate and professional programs but he thinks there is less room to increase tuition at undergraduate programs because borrowing is capped (currently! AT) at fairly low rates. But he offers an even more plausible but disheartening scenario that takes us in exactly the wrong direction.

Because the IDR subsidy is based primarily on post-college earnings, programs that leave students without a degree or that don’t lead to a good job will get a larger subsidy. Students at good schools and high-return programs will be asked to repay their loans nearly in full. Want a free ride to college? You can have one, but only if you study cosmetology, liberal arts, or drama, preferably at a for-profit school. Want to be a nurse, an engineer, or major in computer science or math? You’ll have to pay full price (especially at the best programs in each field). This is a problem because most student outcomes—both bad and good—are highly predictable based on the quality, value, completion rate, and post-graduation earnings of the program attended. IDR can work if designed well, but this IDR imposed on the current U.S. system of higher education means programs and institutions with the worst outcomes and highest debts will accrue the largest subsidies.

Looney does a back of the envelope calculation and estimates that typical graduates in Mechanical Engineering will on average get a 0% subsidy but graduates in Music will get a 96% subsidy, in Drama a 99% subsidy and Masseuses a 100% subsidy on average. This of course is exactly the wrong approach. If we are going to subsidize, we should subsidize degrees with plausible positive spillovers not masseues.

The problem is not just the subsidy but the encouragement this gives to create low-value programs:

- …institutions will have an incentive to create valueless programs and aggressively recruit students into those programs with promises they will be free under an IDR plan….The fact that a student can take a loan for living expenses (or even enroll in a program for purposes of taking out such a loan) makes the loan program easy to abuse. Some borrowers will use the loan system as an ATM, taking out student loans knowing they’ll qualify for forgiveness, and receiving the proceeds in cash, expecting not to repay the loan….I suspect that such abuses will be facilitated by predatory institutions.

Overall, the student loan program, as currently written, is looking to be one of the most costly, inefficient and unwise government programs of the 21st century. As I said in my first post, “fixing” the program is likely to drive ever more increasing intervention into higher education much as has happened with health care. My guess is that no one really thought this albatross through.

John Stuart Mill was Woke and Based

I love that John Stuart Mill was woke and based:

Looking at democracy in the way in which it is commonly conceived, as the rule of the numerical majority, it is surely possible that the ruling power may be under the dominion of sectional or class interests, pointing to conduct different from that which would be dictated by impartial regard for the interest of all. Suppose the majority to be whites, the minority negroes, or vice versâ: is it likely that the majority would allow equal justice to the minority? Suppose the majority Catholics, the minority Protestants, or the reverse; will there not be the same danger? Or let the majority be English, the minority Irish, or the contrary: is there not a great probability of similar evil? In all countries there is a majority of poor, a minority who, in contradistinction, may be called rich. Between these two classes, on many questions, there is complete opposition of apparent interest.

Prediction Markets Should Be Legal

I submitted a public comment on Kalshi’s request to the CFTC to create a prediction market on which political party will be in control of each chamber of the U.S. Congress.

Political election markets have proven themselves to be a powerful tool for forecasting elections and are typically more accurate, timely and complete than alternative methods such as polls. These markets have been widely used by researchers to understand political behaviour, institutions and events. e.g. see the research summarized here

https://www.nber.org/papers/w18222

and an important application to understanding the costs of war here:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2008.00750.x

Political election markets are also useful to hedgers, traders and other market participants to help them predict and incorporate information about risks into asset prices.

Markets similar to political election markets have been used to predict other important events such as the prospects for war or scientific breakthroughs and have been adopted by firms to better estimate sales forecasts and other relevant events.

The United States has pioneered the use of these innovative markets and we should continue to lead in creating better means of aggreating information to improve the quality of decision making.

The David J. Theroux Chair in Political Economy: Job Opportunity

The Independent Institute is seeking a capable intellectual leader with a deep and energetic commitment to classical liberal principles, an ability to communicate and connect with others, and the qualities and drive to help perpetuate David J. Theroux’s vision in the research program of the organization in the decades ahead.

As part of Independent’s commitment to excellence, continuous improvement and teamwork, the David J. Theroux Chair is responsible for ensuring that all research activities have intrinsic intellectual merit and would have a significant impact in the service of Independent’s mission to boldly advance peaceful, prosperous, and free societies, grounded in a commitment to human worth and dignity.

The Theroux Chair will ensure that Independent’s scholarship, research and peer-reviewed publications adhere to the highest scholarly standards; provide leadership in support of acquisitions, peer review, author relations, and editorial quality; collaborate with Independent’s other experts to ensure that research, content, and promotional plans and activities are appropriately aligned; and in broad terms sustain Independent’s reputation as a well-respected policy institute.

The Theroux Chair will network with scholars, academic and policy organizations, and professional organizations, in leveraging and promoting mutual efforts in advancing classical liberal analytical methods and aspirations. As opportunities present themselves, the Theroux Chair will organize conferences, symposia, and other events.

What is the incentive here for investment in future capacity?

The EU is planning to raise €140bn from energy companies’ profits to soften the blow of record-high prices this winter in what would amount to a new bloc-wide levy in response to the crisis over Ukraine.

A proposed windfall tax on power companies that do not burn gas, the price of which has recently soared, would be accompanied by other measures on fossil fuel groups…

The commission proposal would set a mandatory threshold for prices charged by companies that produce low-cost, non-gas energy, such as nuclear and renewables groups.

Companies would have to give EU states the “excess profits” generated beyond this level, which the commission seeks to set at €180/MWh. But member states would be free to put in place lower thresholds of their own.

Here is more from the FT.

The supply side of the labor market was indeed a factor

It wasn’t just the demand side at fault, labor supply was misbehaving as well. Put aside the Twitter one-liners about video games, the evidence is now overwhelming, as I argue in my latest Bloomberg column. Here is one excerpt:

Fast forward to the pandemic and early 2021. It was the conventional wisdom that inflation would be very difficult to create, because demand is usually deficient and supply can respond to any surge in spending, thereby offsetting inflationary pressures. That was the consensus formed after the Great Recession, and it turned out to be spectacularly wrong. Now the US is living with its consequences, namely high inflation with a possible recession to follow.

The evidence is piling up that the US has been suffering from a deficit of human capital. For instance, a recent report showed that US life expectancy first stalled and then has been falling. In other words, current Americans — or at least some subset of them — are having trouble just staying alive.

And:

Another trend is that many people are marrying later in life, or not marrying at all, especially in the lower socioeconomic strata. That’s not necessarily bad. Still, an era characterized by fussiness in marriage may also be characterized by fussiness in choice of job. And marriage itself may be a spur for getting a job, especially for men. Again, individual choices — and not just insufficient demand — seem to have been a significant reason that labor markets were so slow to recover in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

It is also instructive to look at what is called “quiet quitting.” The US economy is close to full employment, in part due to an extreme overstimulation of demand. Even so, the human capital problems and labor market malfunctions haven’t gone away — they’ve just been pushed into other facets of the workplace experience. According to a recent Gallup poll, at least 50% of the US workforce are “quiet quitters.” Meanwhile, labor productivity is down dramatically, and though the measure is imprecise, it is hardly a good sign.

Many commentators are quite willing to entertain the hypothesis that there are significant problems with human capital in the US. But when discussion turns to the slow labor-market recovery following the Great Recession, all the blame is put on a weak monetary and fiscal response.

Recommended.

Covid-19 and labor supply

We show that Covid-19 illnesses persistently reduce labor supply. Using an event study, we estimate that workers with week-long Covid-19 work absences are 7 percentage points less likely to be in the labor force one year later compared to otherwise-similar workers who do not miss a week of work for health reasons. Our estimates suggest Covid-19 illnesses have reduced the U.S. labor force by approximately 500,000 people (0.2 percent of adults) and imply an average forgone earnings per Covid-19 absence of at least $9,000, about 90 percent of which reflects lost labor supply beyond the initial absence week.

That is from a new NBER working paper, by Gopi Shah Goda and Evan J. Soltas, of relevance both to Long Covid and our current human capital crisis.

Richard Hanania interviews me

78 minutes. With transcript. It starts off as a normal “talent conversation,” but soon takes other paths. We discuss feminization in some detail, libertarianism too. Here is part of Richard’s summary:

Another one of Tyler’s traits that came out in this conversation is his detached skepticism regarding fashionable intellectual trends. For example, I’d taken it for granted that social media has made elite culture more pessimistic and angry, but his answer when I asked about the topic made me reconsider my view.

Interesting throughout, and here is one excerpt:

Tyler: It seems to me social media are probably bad for 12- to 14-year-old girls, and probably good for most of the rest of us. That would be my most intuitive answer, but very subject to revision.

Richard: I think it’s good. I mean, I think it’s good for me…

Tyler: But they’re bad for a lot of academics. I guess, they get classified in…

Richard: They might be at the…

Tyler: They get lumped in with the 12 to 14-year-old girls, right?

Richard: [laughs] There might be a similarity there.

Tyler: They have something in common.

Recommended.

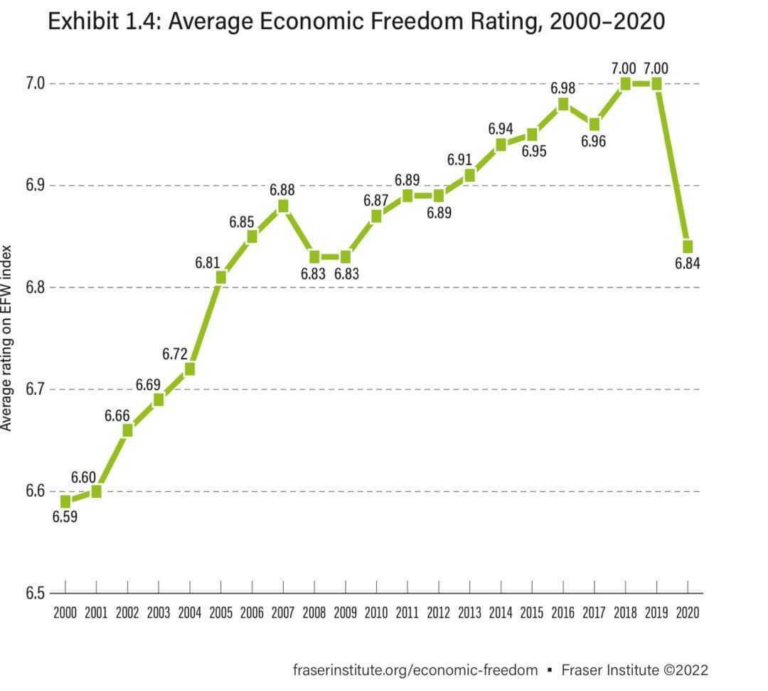

US Economic Freedom is Falling

A big drop in Economic Freedom, mostly due to pandemic policies. Not surprising but will we recover? This is from the just released Economic Freedom of the World 2022 Annual Report.