Category: Economics

OTC Prescriptions Save on Medical Costs

The excellent Joel Selanikio writes on medical disruption from the rise of self-care:

I’ve been asked many times whether I think that AI will replace doctors. Never once have I been asked if I thought that OTC drugs could replace doctors. But that’s exactly what they have done: every time a drug switches from prescription to OTC, the total number of doctor visits drops.

In fact, a 2012 study by Booz concluded that

“if OTC medicines did not exist, an additional 56,000 medical practitioners would need to work full-time to accommodate the increase in office visits by consumers seeking prescriptions for self-treatable conditions.”

Fifty-six thousand doctors that we don’t need because of OTC drugs; that’s almost 6% of the practicing doctors in America. Think of the effect on healthcare costs.

Selanikio gives more examples of how AI plus super-computers, i.e. cell phones, can lead to better, at-home diagnosis and fewer physician hours (and more here). More generally, due to the Baumol effect the only way to save on medical care costs is by using less labor and more capital–this is rarely recognized.

A Vision of Metascience

Lots to praise and to ponder in this excellent piece by Michael Nielsen and Kanjun Qiu on improving the discovery ecosystem with metascience. The piece contains some pop-ideas to stimulate thinking such as:

- Fund-by-variance: Instead of funding grants that get the highest average score from reviewers, a funder should use the variance (or kurtosis or some similar measurement of disagreement5) in reviewer scores as a primary signal: only fund things that are highly polarizing (some people love it, some people hate it). One thesis to support such a program is that you may prefer to fund projects with a modest chance of outlier success over projects with a high chance of modest success. An alternate thesis is that you should aspire to fund things only you would fund, and so should look for signal to that end: projects everyone agrees are good will certainly get funded elsewhere. And if you merely fund what everyone else is funding, then you have little marginal impact6,7.

But it’s really not about one one idea but about understanding why scientific tools are rarely applied to science itself and what can we do to improve metascience. Lots of bad news but there are some positive examples. Thereplication revolution (no longer a crisis!) appears to be working:

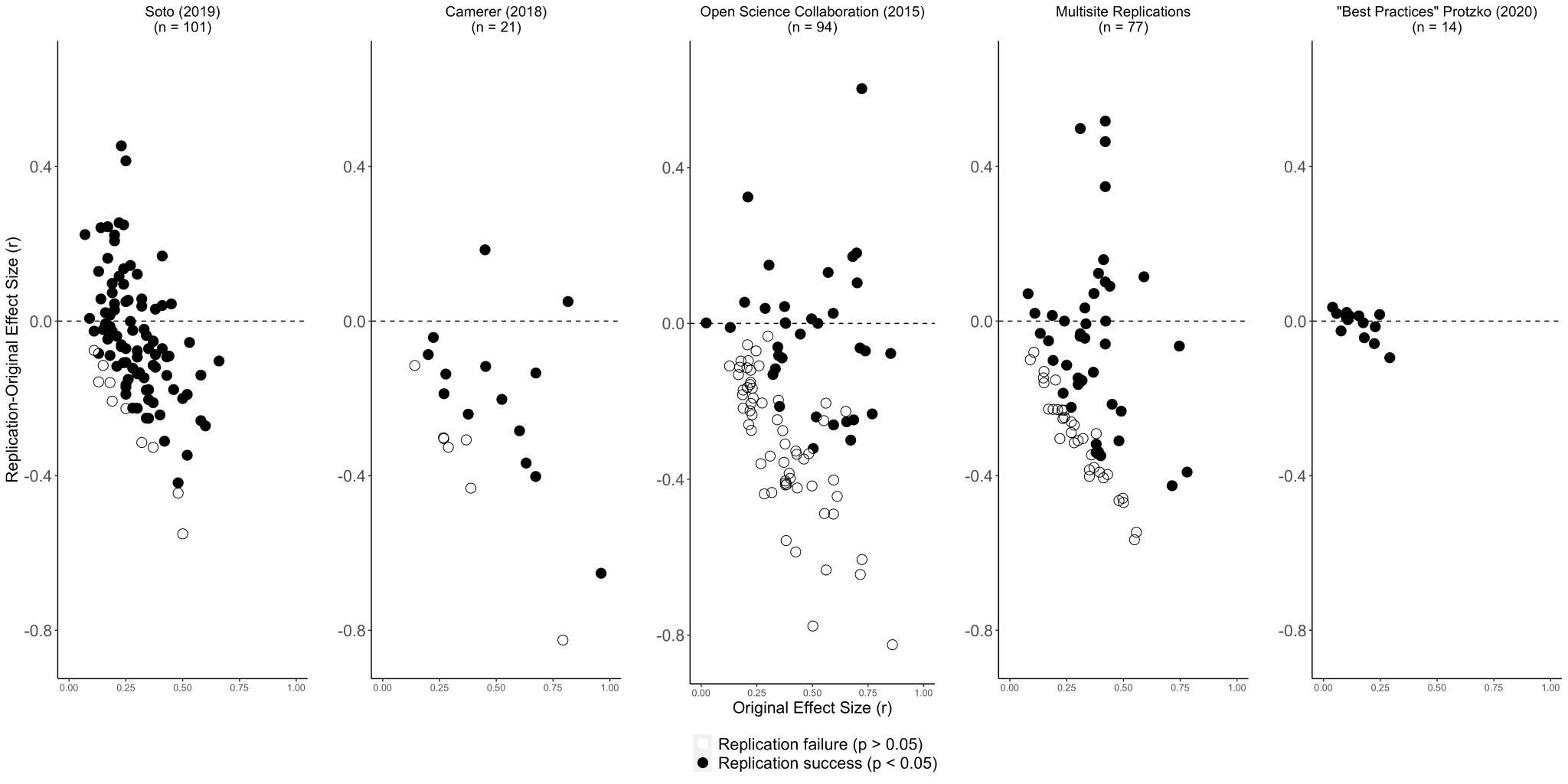

There are encouraging signs that pre-registered study designs like this are helping address the methodological problems described above. Consider the following five graphs. The graphs show the results from five major studies89, each of which attempted to replicate many experiments from the social sciences literature. Filled in circles indicate the replication found a statistically significant result, in the same direction as the original study. Open circles indicate this criterion wasn’t met. Circles above the line indicate the replication effect was larger than the original effect size, while circles below the line indicate the effect size was smaller. A high degree of replicability would mean many experiments with filled circles, clustered fairly close to the line. Here’s what these five replication studies actually found:

As you can see, the first four replication studies show many replications with questionable results – large changes in effect size, or a failure to meet statistical significance. This suggests a need for further investigation, and possibly that the initial result was faulty. The fifth study is different, with statistical significance replicating in all cases, and much smaller changes in effect sizes. This is a 2020 study by John Protzko et al90 that aims to be a “best practices” study. By this, they mean the original studies were done using pre-registered study design, as well as: large samples, and open sharing of code, data and other methodological materials, making experiments and analysis easier to replicate…In short, the replications in the fifth graph are based on studies using much higher evidentiary standards than had previously been the norm in psychology. Of course, the results don’t show that the effects are real. But they’re extremely encouraging, and suggest the spread of ideas like Registered Reports contribute to substantial progress.

The story of Brian Nosek is very interesting:

Many people have played important roles in instigating the replication crisis. But perhaps no single person has done more than Brian Nosek. Nosek is a social psychologist who until 2013 was a professor at the University of Virginia. In 2013, Nosek took leave from his tenured position to co-found the Center for Open Science (COS) as an independent not-for-profit (jointly with Jeff Spies, then a graduate student in his lab). Nosek and the COS were key co-organizers of the 2015 replication paper by the Open Science Collaboration. Nosek and the COS have also been (along with Daniël Lakens, Chris Chambers, and many others) central in developing Registered Reports. In particular, they founded and operate the OSF website, which is the key infrastructure supporting Registered Reports.

…The origin story of the COS is interesting. In 2007 and 2008, Nosek submitted several grant proposals to the NSF and NIH, suggesting many of the ideas that would eventually mature into the COS95. All these proposals were turned down. Between 2008 and 2012 he gave up applying for grants for metascience. Instead, he mostly self-funded his lab, using speaker’s fees from talks about his prior professional work. A graduate student of Nosek’s named Jeff Spies did some preliminary work developing the site that would become OSF. In 2012 this got some media attention, and as a result was noticed by several private foundations, including a foundation begun by a billionaire hedge fund operator, John Arnold, and his wife, Laura Arnold. The Arnold Foundation reached out and rapidly agreed to provide some funding, ultimately in the form of a $5.25 million grant.

To do this, Nosek had to leave the University of Virginia? Why? He was then attacked by many in the scientific community. Why? Read the whole thing for much more.

Treason!

The International Shipping panel of the Maritime Transportation System National Advisory Committee, a quasi-official advisory board, is not happy with the Cato Institute and Mercatus.

The Dispatch: After a March 21, 2020 meeting, the international shipping subcommittee sent draft recommendations to the Transportation Department’s Maritime Administration, according to a document the Cato Institute recently obtained from the government. The document, reviewed by The Dispatch, broadly discusses the problems of an aging U.S. fleet and insufficient shipping capacity.

Nestled among bullet points recommending policy changes to fix those problems is one labeled, “Unequivocal support of the Jones Act.”

Beneath it: “Charge all past and present members of the Cato and Mercatus Institutes with treason.

If these rent-seeking gangsters think this is going to dissuade Cato and Mercatus scholars from continuing to attack the awful Jones Act they are very much mistaken.

Driving Buy: Pollution, Customers and Development

The literature on air pollution continues to grow. In an impressive paper, Bassi et al. show that firms in Uganda locate on busy roads, Busy roads are more polluted but there are more customers driving and they rely on direct customer acquisition, rather than advertising or marketing, to get customers.

Location choice thus entails a trade-off between pollution exposure, which we verify to be mainly driven by road traffic, and access to customers. We also use our survey data to argue that the benefits can be explained primarily by the fact that, as it is typically the case across the developing world, firms sell locally through face-to-face interactions and do not have any other means to access customers than to be as visible as possible to them. Therefore, proximity to busy roads is essential.

Locating along busy roads increases profits per worker but reduces life expectancy of workers by about two months. A two month loss in life expectancy is substantial. Uganda is so poor (GDP per-capita ~$720), however, that the authors find that an (imaginary) policy of randomly allocating firms would not be cost-effective. Randomly allocating firms, however, is only one potential policy–others include using more buses or instituting a congestion tax. India has higher per capita GDP than Uganda so if all else were equal many such policies would pay in India. One type of “firm” that I have seen locate on congested roads in India is beggars and street sellers. It’s obvious that they go where the customers are but at the price of locating in very polluted areas.

I argued in India recently that reduced pollution could increase GDP. I continue to think that is true on the margin–there is some low-hanging fruit.

In other pollution news. It is clear that pollution papers are becoming a growth industry and thus there are bound to be green jelly bean problems. I haven’t read either closely but I did note that Roy et al. find that pollution increases mutual fund errors and Du finds that pollution increases racist tweets. Well, maybe. The new pollution literature is credible but remember to trust literatures not papers.

Overrated or underrated?

Ramagopal asks: Peter Bauer, Mises, Joan Robinson

1. Peter Bauer is underrated. He was a brilliant development economist who wrote seminal early and detailed books on the rubber sector and also networks of West African trade. He also recognized the importance of the informal sector early on. He then moved into a more polemic mode, writing books on market-oriented development strategies and very critical of foreign aid. I believe at the time he was largely correct about foreign aid, though I would recognize also that since then the quality and effectiveness of foreign aid has improved considerably, most of all because the receiving governments have on average improved in quality.

His family had a coat of arms, linked above at his name.

I once met Bauer at a seminar at NYU, way back when. He reminded me of a character from LOTR and he had a thick mane of white hair. I believe Bauer was also one of the first well-known economists to come out as gay.

2. Mises is underrated. His 1922 book Socialism is still the best and also historically most important critique of socialism, ever. His earlier articles about the impossibility of economic calculation under socialism are among the most important economics articles, ever. Those are already some pretty important contributions, and yet he is often talked of as a crank, perhaps because in part some of his followers were indeed cranks.

Liberalism I quite like. His book Bureaucracy is underdeveloped but still pretty interesting, and his hypotheses about the logic of cascading interventionism, if not entirely correct, still are an important contribution to public choice. They do explain a lot of the data. Human Action is big, cranky, and dogmatic, but for some people a useful tonic and alternative to the usual stuff. I can’t say I have ever really liked it, and in an odd way the whole emphasis on “Man acts” undoes at least one part of marginalism. The early Theory of Money and Credit was a pretty good early 20th century book on monetary theory.

Hayek somehow ended up as “the reasonable face of classical liberalism,” but in fact Mises was far more politically correct by current standards.

Obviously there is a sliver of people who very much overrate Mises. Here is a guy who hardly anyone rates properly. I’m still sticking with considerably underrated.

3. Joan Robinson’s Theory of Imperfect Competition was a very important book, and it laid the groundwork for a lot of later thinking about market structure, both geometrically and conceptually. But she didn’t understand actual economics, was a Maoist, and seemed to like the regime of North Korea. So I have to say overrated. Her Accumulation of Capital also was no great shakes, though hardly her greatest sin. Her growth theory was far too Marxian, and far too fond of “Golden Rule” constructs, which are mechanistic rather than insightful as models ought to be. Her writings in Economic Philosophy were not profound. So she has one truly major contribution, but I can’t get past the really bad stuff.

Investment advice from Russell Napier

First of all: avoid government bonds. Investors in government debt are the ones who will be robbed slowly. Within equities, there are sectors that will do very well. The great problems we have – energy, climate change, defence, inequality, our dependence on production from China – will all be solved by massive investment. This capex boom could last for a long time. Companies that are geared to this renaissance of capital spending will do well. Gold will do well once people realise that inflation won’t come down to pre-2020 levels but will settle between 4 and 6%. The disappointing performance of gold this year is somewhat clouded by the strong dollar. In yen, euro or sterling, gold has done pretty well already.

Here is the full discussion, interesting throughout. He also says to expect widespread capital controls. To be clear, none of this is investment advice from me.

German fiscal policy vindicated

And since German politicians have insane views on fiscal policy, they will probably say that the current experience actually validates their prior two decades of excessively tight fiscal policy. In reality, the current situation mostly shows that Germany wasted an opportunity to take advantage of a prolonged period of negative interest rates to create a national high-speed rail network³ and to make massive investments in home insulation.

That is from a Matt Yglesias Substack, gated but worth paying for. I agree Germany should have spent more on home insulation, but there are several ways of doing that in terms of the macro fiscal picture.

The broader point is that the current situation does in fact validate Germany’s prior two decades of tight fiscal policy. I think most of us agree that you should run budget surpluses in relatively good times, and budget deficits in relatively bad times. It now turns out those were in fact the relatively good times. The Germans worried that might be the case, and now it turns out they were right.

Telemedicine is Dying

Bloomberg: Prior to the Covid era, telehealth accounted for less than 1% of outpatient care, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Telehealth services have since surged, at their peak accounting for 40% of outpatient visits for mental health and substance use.

Unfortunately, as I warned last year telemedicine is being wound back as regulations which were lifted for the pandemic emergency are put back into place.

Telemedicine exploded in popularity after COVID-19 hit, but limits are returning for care delivered across state lines.

…Over the past year, nearly 40 states and Washington, D.C., have ended emergency declarations that made it easier for doctors to use video visits to see patients in another state, according to the Alliance for Connected Care, which advocates for telemedicine use.

…To state medical boards, the patient’s location during a telemedicine visit is where the appointment takes place. One of MacDonald’s hospitals, Massachusetts General, requires doctors to be licensed in the patient’s state for virtual visits.

I know people who have had to travel over the Virginia/Maryland border just to find a wifi spot to have a telemedicine appointment with their MD physician. Ridiculous.

….telemedicine innovations pioneered during the pandemic should remain as options. No one doubts that some medical services are better performed in-person nor that requiring in-person visits limits some types of fraud and abuse. Nevertheless, the goal should be to ensure quality by regulating the provider of medical services not regulating how they perform their services. Communications technology is improving at a record pace. We have moved from telephones to Facetime and soon will have even more sophisticated virtual presence technology that can be integrated with next generation Apple watches and Fitbits that gather medical information. We want medical care to build on the progress in other industries and not be bound to 19th and 20th century technology.

Plod has a bunch of questions

From my request for requests, here goes:

– What does the NYT do well? And conversely what are they bad at?

– What is your theory on the rising lack of male ambition?

– Why do modern fantasy authors (Martin, Rothfuss, others) not finish their works?

– If you were chief economist czar of the US, what is the policy would you implement first? In the UK?

– Will non-12-tone equal temperament music ever become popular?

– What do you think will become of charter cities like Prospera?

I will do the answers by number:

1. The New York Times can publish superb culture pieces, most of all when they are not pandering on PC issues. Their music and movie reviews are not the very best, but certainly worth the time. International coverage is high variance, but they have plenty of articles with information you won’t find elsewhere. Some of the finest obituaries. The best parts of the Op-Ed section are indispensable, and the worst parts are important to read for other reasons. Perhaps most importantly, the NYT has all sorts of random articles that are just great, even if I don’t always like the framing. Try this one on non-profit hospitals.

On the other side of the ledger, the metro and sports sections I do not very much read (probably they are OK?). The business section has long been skimpy, and is not currently at its peak. Historical coverage with racial angles can be atrocious. The worst Op-Eds are beyond the pale in their deficient reasoning, and there are quite a few of them. On “Big Tech” the paper is abysmal, and refuses to look the conflict of interest issues in the eye. They just blew it on a new Covid study. The book review section used to be much better, I think mainly because it has become a low cost way to appease the Wokies.

2. Male ambition in the United States is increasing in variance, not waning altogether. But on the left hand side of that distribution I would blame (in no particular order): deindustrialization, women who don’t need male financial support anymore, marijuana, on-line pornography, improved measurement of worker quality, the ongoing rise of the service sector, too much homework in schools, better entertainment options, and the general increasing competitiveness of the world, causing many to retreat in pre-emptive defeat.

3. Male fantasy writers do not finish their works because those works have no natural ending. There is always another kingdom, a lost family member, a new magic power to be discovered, and so on. And the successful fantasy authors keep getting paid to produce more content, and their opportunity cost is otherwise low. Why exactly should they tie everything up in a neat bow, as Tolkien did with the three main volumes of LOTR?

4. For the United States, I would have more freedom to build, massive deregulations of most things other than carbon and finance, and much more high-skilled immigration, followed by some accompanying low-skilled immigration. For the UK I would do broadly the same, but also would focus more on human capital problems in northern England as a means of boosting economic growth.

5. Non-12-tone equal temperament music is for instance very popular in the Arabic world, and has been for a long time.

6. I have been meaning to visit Prospera, but have not yet had the chance to go. I expect to. My general worries with charter cities usually involve scale, and also whether they will just get squashed by the host governments, which almost by definition are dysfunctional to begin with. Most successful charter cities in history have had the support of a major outside hegemon, such as Hong Kong relying on Britain.

Subsidizing lower gas consumption

1) Why is all of the policy discussion in Europe focused on subsidizing consumption of gas rather than on subsidizing the reduction in consumption of gas. The latter approach is consistent with the German/European policy of moving to greater reliance on renewable energy. Subsidizing reduction in consumption also reduces the risk of shortages if the Northern winter is severe. The policy is straightforward to implement for households but is a little more difficult for to implement for businesses as some may profitably choose to reduce employment and or output which would be politically difficult. However, this problem can be remedied with he combination of, for example, an employment subsidy together with the subsidy paid for reduced use of gas.

That is from my email, from economist Don Harding.

Lifecycle Investing

and

Investors often think of diversification as a free lunch—it allows them to maintain returns while reducing risk. But most people only get part of diversification right, and that can hurt them later in life.

With traditional diversification, people spread money around different kinds of investments to mitigate risk. That approach misses a key opportunity: “diversifying” how you invest over time.

Most people start investing with a small amount of money, because that is all they can afford, and ramp it up as their earnings grow. But investing so much later in life unnecessarily puts people at greater risk when they are close to retirement. They end up with far greater exposure to stock-market risk in their 50s and 60s than in their 20s and 30s, even if they are buying diversified mutual funds.

We propose a different method: People ought to borrow money to make their initial investments larger, so that they can invest closer to the same amount every year over their lifetime. Think of investing $2 a decade steadily for three decades, instead of $1 for the first, $2 for the next and $3 for the third.

…Sound risky? Consider that young people do the same thing with housing when they borrow money to buy a house they live in for decades—and there the leverage often involves borrowing $9 for every $1 of equity. We propose borrowing only $1 for each $1 invested. Limiting ourselves to 2:1 leverage means we don’t hit a perfectly even market exposure over time, but gets us closer to that ideal.

Most people won’t do this because unlike a home-mortgage it’s a non-standard idea. It could be standardized, however, with retirement planning products. Regardless, I agree with Ayres and Nalebuff that young people should be 100% in equities. Of course, the equity-basket should be diversified, national and internationally, and young people should follow a buy and hold strategy while being very aggressive on the equity-debt mix. Also, if, as you get older, you expect to make a bequest you should continue to be aggressive on the portion of your portfolio you expect be passed on to your beneficaries.

Price caps on Russian oil and gas

A number of you have written in to ask what I think of the recent economists’ letter to Janet Yellen, proposing such price caps. I don’t disagree with any of their economics, but I am less convinced this is a good idea. This strikes me as a paramount example of what I call “foreign policy first.” There is some chance that Russia initiates a nuclear attack, or takes some other set of drastic steps. Does this price cap raise or lower that chance? I genuinely do not know. And thus for that reason I am agnostic about the policy. The nuclear expected value calculations would seem to outweigh the other aspects of the proposal, and those calculations are beyond my ability to assess with much accuracy.

Often, when I have nothing to say, it is because I do not know exactly what to say.

Famous economists write a letter to Janet Yellen

Here is the letter, they argue for a price cap on Russian oil and gas:

As envisaged by the G7, the price cap would set a maximum price that Russian oil could be traded in conjunction with G7 services. This price, set in dollars, would be substantially below the world price, yet above the marginal cost of production in Russia. To use US, UK, EU, and allied financial services (such as insurance, credit, and payments), market participants will need to attest that all qualifying purchases are at or below this threshold.

Given the importance of participating countries for global finance and for shipping, compliance with this cap will create pressure for a lower price on Russian oil moved by tanker. While we do not expect all trades will be performed under the price cap, its existence should materially increase the bargaining power of private and public sector entities that buy Russian oil.

The price cap maintains economic incentives for Russia to produce current volumes. In April 2020, when the price of the Brent benchmark was close to $20, Russia continued to supply oil to world markets, because that price was above the cost of production in many or most existing Russian oil fields. Russian has little or no available onshore storage, and since shutting down and restarting oil fields is expensive and risky, it was more profitable for Russia to continue producing in the presence of low prices. The price of Brent now is around $96 per barrel, but Russia receives significantly less due to the “Urals discount”. This discount is caused by the perceived stigma of buying Russian products for some customers; they decline to bid for Russian oil, which reduces effective demand and lowers the price that the remaining customers need to pay.

The oil price cap proposal would effectively institutionalize the Urals discount and consequently further lower the dollar value of the Russian government’s primary revenue stream.

Do read the whole thing, the list of signers is on the bottom.

The Nobel Prize Goes to Bernanke and Diamond and Dybvig

The Nobel Prize Goes to Bernanke and Diamond and Dybvig for their work on banking. Bernanke seems like an obvious choice. Doesn’t he have one already? Well, no. But few people have had as stellar an academic career topped by another stellar career in public policy. A few economists have became famous politicians but it’s difficult to think of any economists whose career in public policy consisting of implementing, applying and testing the knowledge they built in academia.

Bernanke, of course, wrote key papers on the Great Depression–the Nobel committee points especially to his 1983 paper Non-Monetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression which showed that it wasn’t just the decline of the money supply that mattered (ala Friedman and Schwartz) but also the decline of the credit supply. Another way of putting this is that the waves of bank failures in the 1930s reduced the economy’s ability to produce output in a way that could not be countered simply by printing more money. As Tyler and I emphasize in our textbook, Modern Principles, nominal and real shocks are often intertwined. Bernanke then famously brought this line of thinking to his actions as head of the Federal Reserve during the 2008-2009 Financial Crises. Bernanke believed that it was critical to rescue the banks and the shadow banks not because he was beholden to financial interests (he was not a Wall Street guy) but because he believed the banks were a critical bridge between savers and investors and if that link were broken the results would be catastrophic. Bernanke rescued the banks to save the bridges.

I’m also a fan of a second, somewhat less well-known paper that Bernanke also published in 1983 (the Annus Mirabilis paper phenomena), Irreversibility, Uncertainty, and Cyclical Investment. Bernanke in this paper pioneered what would later become the real options analysis of investment, i.e. thinking about investment as an option, akin to a financial option. Thus, investment has two key features–you can usually wait a little bit to gather more information before investing but once you strike, the investment is sunk, i.e. irreversible. These two features have important implications for investment decisions and writ-large business cycles. In particular, Bernanke showed something surprising which he dubbed “the bad-news principle.” The bad-news principle says that only the expected severity of bad news matters for the decision whether to invest, good news should not matter at all. The reason is that the real decision an investor must make is whether to invest immediately or wait a little bit to learn more but what makes waiting valuable is not the possibility of good news but the possibility of avoiding mistakes. Avoiding mistakes is what investors care about on the margin. In turn, what that means is that avoiding bad news–creating downside insurance–can generating a huge upside because it can trigger a wave of investment. Bernanke also took this lesson to his role at the Federal Reserve.

Large amounts have been written on Bernanke already, of course, including his own memoir and I don’t think I can add much to that torrent beyond emphasizing the remarkable consistency of Bernanke’s thoughts and actions from academia to central banking.

Diamond and Dybvig are responsible for the now canonical model of banking. You can read Tyler below for more details on Bernanke and an explanation of the DD model.

The economic contributions of Ben Bernanke

Ben Bernanke is best known for being Fed chairman, but he has a long and distinguished research career of great influence. Here are some of his contributions:

1. In a series of papers, often with Alan Blinder, Bernanke argued that “credit and money” are a better leading indicator than money alone. And more generally he helped us rethink the money-income correlation that was so promoted by Milton Friedman. This work was more correct than not, but since money as a leading indicator has fallen out of favor (partially because of Bernanke’s own later actions!), these contributions are seen as less important than was the case for about fifteen years. See also this piece on the (earlier) import of the federal funds rate as a measure of monetary policy. Ben’s body of work on money and credit was what first brought him renown.

2. Bernanke has a famous 1983 paper on how the breakdown of financial intermediation was a key component of the Great Depression. Earlier, Milton Friedman had stressed the import of the contraction of the money supply, but Bernanke’s work led to a much richer picture of how the collapse happened. Savers were cut off from borrowers, due to bank failures, and the economy could not mobilize its capital very effectively. This article also shows the integration between Bernanke’s work and that of Diamond and Dybvig. This piece has held up very well.

3. Bernanke has related work, with Gertler, Gilchrist and others, on how financial problems can worsen a business cycle. This work of course fed into his later decisions as chairman of the Fed. In yet other work, Bernanke showed how economic downturns can lower the value of collateral, thus squeezing the lending process and exacerbating business cycle downturns.

4. Bernanke’s doctoral dissertation was on the concepts of option value and irreversible investment. Modest increases in business uncertainty can cause big drops in investment, due to the desire to wait, exercise “option value,” and sample more information. This work was published in the QJE in 1983. I have long felt Bernanke does not receive enough credit for this particular idea, which later was fleshed out by Pindyck and Rubinfeld.

5. Bernanke wrote plenty of pieces — this one with Mishkin — on inflation targeting as a new means of conducting monetary policy. Those were the days! Much of the OECD lived under this regime for a few decades.

6. Here is Ben with co-authors: “We first document that essentially all the U.S. recessions of the past thirty years have been preceded by both oil price increases and a tightening of monetary policy…” Uh-oh!

7. Here is 2004 Ben on what to do when an economy hits the zero lower bound. Here is Ben on earlier Japanese monetary policy, and what he called their “self-induced paralysis” at the zero bound. He really was in training for the Fed job all those years. Here is Ben on “The Great Moderation.” Here is 1990 Ben on clearing and settlement during the 1987 crash.

8. Ben has made major contributions to our understanding of how the gold standard and international deflationary pressures induced the Great Depression, transmitted it across borders, and made it much worse. This work has held up very well and is now part of the mainstream account. And more here.

9. Bernanke coined the term “global savings glut.”

Here is all the Swedish information on the researchers and their work. I haven’t read these yet, but they are usually very well done. Here is Ben on scholar.google.com.

In sum, Ben is a broad and impressive thinker and researcher. This prize is obviously deserved. In my admittedly unorthodox opinion, his most important work is historical and on the Great Depression.