Category: Economics

Mark Skousen on AEA masking

I called the Hilton Riverside, headquarters hotel for the AEA meetings, and asked if they have any mask or vaccine mandates. They said “none.” I’ll speak at the New Orleans Investment Conference at the same hotel in October, and the organizers aren’t mandating masks or vaccines. Overseas it’s the same. I’m speaking at the World Knowledge Forum in September in Seoul and attending the Mont Pelerin Society meetings in October in Oslo. No masks or shots required.

Here is more from the WSJ. I’ll be speaking in Canada soon — Canada!…risk-averse, locking down for longer, many fewer people died there Canada. No masks or boosters required.

Public policies as instruction

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

Minimum-wage hikes also send the wrong message to voters. Yes, there is literature suggesting that such increases destroy far fewer jobs than previously thought, and may have considerable ancillary benefits, such as preventing suicides. Still, a minimum wage is a kind of price control, and most price controls are bad. Voters may not realize the subtle ways in which minimum-wage hikes are different (and better) from most price controls. Instead, they get the message that the path to higher living standards is through government fiat, rather than better productivity.

If you think that far-fetched, consider the initiative passed by the California Senate this week. The bill would create a government panel to set wages and workplace standards for all fast-food workers in the state, and labor-union backers hope the plan will spread nationally. That may or may not happen, but those are precisely the paths that are opened up by minimum-wage advocacy. Many people hear a bigger and more ambitious message than the one the speaker wishes to send.

So what messages, in the broadest terms, should policies convey? I would like to see increased respect for cosmopolitanism, tolerance, science, just laws, dynamic markets, free speech and the importance of ongoing productivity gains. Obviously any person’s list will depend on his or her values, but for me the educational purposes are more than just a secondary factor. When it comes to prioritizing reforms, the focus should be on those that will “give people the right idea,” so to speak.

The mere fact that you are uncertain about such effects does not mean you can or should ignore them. They are there, whether you like it or not.

Mandated vaccine boosters for the AEA meetings?

Yes, the new AEA regulations will mandate vaccine boosters for attendance at the New Orleans meetings. Not just two jabs but yes boosters, at least one of them.

Like the N-95 (or stronger) mask mandate, this seems off base and possibly harmful to public health as well. Here are a few points:

1. The regulations valorize “booster with an older strain,” and count “infection with a recent strain” for nothing. In fact, the latter is considerably more valuable, most of all to estimate a person’s public safety impact on others. So the regulations simply target the wrong variable.

1b. People who are boosted might even be less likely to have caught the newer strains (presumably the boosters are at least somewhat useful). Thus they are potentially more dangerous to others, not less, being on average immunologically more naive. Ideally you want a batch of attendees who just had Covid two or three months ago.

2. More than three-quarters of Americans have not had a booster to date. Very likely the percentage of potential AEA attendees with boosters stands at a considerably higher level. Still, this is a fairly exclusionary policy, and pretty far from what most Americans consider to be an acceptable regulation.

2b. To be clear, I had my booster right away, even though I expected it would make me sick for two days (it did). I am far from being anti-booster. I am glad I had my booster, but I also understand full well the distinction between “getting a booster at the time was the right decision,” and “we should mandate booster shots today.” They are very different! Don’t just positively mood affiliate with boosters. Think through the actual policies.

3. Blacks are a relatively undervaccinated group, and probably they are less boosted as well. The same may or may not be true for black potential AEA attendees, but it is certainly possible. After all the talk of DEI, and I for one would like to see more inclusion, why are we making inclusion harder? And for no good medical reason.

3b. How about potential attendees from Africa, Latin America, and other regions where boosters are harder to come by? What are their rates of being boosted? Do they all have to fly to America a few days earlier, line up boosters, and hope the ill effects wear off by the time of the meetings? Why are we doing this to them?

3c. Will the same booster requirements be applied to hotel staff and contractors? Somehow I think not. Maybe that is a sign the boosters are not so important for conference well-being after all?

4. Many people are in a position, right now, where they should not boost. Let’s say you had Covid a few months ago, and are wondering if you should get a booster now or soon. I looked into this recently, and found the weight of opinion was that you should wait at least six months for your immune system to process the recent infection. That did not seem to be “settled science,” but rather a series of judgments, admittedly with uncertainty. So now let’s take those people who were not boosted, had a new strain of Covid recently, and want to go to the AEA meetings. (The first two of three there cover a lot of people.) They have to get boosted. And in expected value terms, boosting is bad for them. Did this argument even occur to the decision-makers at the AEA?

5. The AEA mentions nothing about religious or other exceptions to the policy. Maybe there are “under the table” exceptions, but really? Why not spell out the actual policy here, and if there are no exceptions come right out and tell us. And explain why so few other institutions have chosen the “no exceptions” path, and why the AEA should be different. (As a side note, it is not so easy to process exceptions for the subset of the 13,000 possible attendees who want them. Does the AEA have this capacity?)

Again, this is simply a poorly thought out policy, whether for N-95 masks or for boosters. I hope the AEA will discard it as soon as possible. Or how about a simple, open poll of membership, simple yes or not on the current proposal?

Insurance markets in everything

Xcel confirmed to Contact Denver7 that 22,000 customers who had signed up for the Colorado AC Rewards program were locked out of their smart thermostats for hours on Tuesday.

“It’s a voluntary program. Let’s remember that this is something that customers choose to be a part of based on the incentives,” said Emmett Romine, vice president of customer solutions and innovation at Xcel.

Customers receive a $100 credit for enrolling in the program and $25 annually, but Romine said customers also agree to give up some control to save energy and money and make the system more reliable.

Basically their AC was shut off and some of the homes had temperatures as high as 88 Fahrenheit. Sounds like an OK arrangement to me! Here is the full story, via Tom Hynes.

“Follow the science”

To attend the 2023 ASSA Annual Meeting, all registrants will be required to be vaccinated against COVID-19 and to have received at least one booster. High-quality masks (i.e., KN-95 or better) will be required in all indoor conference spaces. These requirements are planned for the well-being of all participants.

That is from the AEA. Really!!??

Even the Arlington County Public Library is doing better than that. Did someone do a cost-benefit analysis? If so, may I see it? And if this is optimal, why are no private American businesses following suit? (Can you name one, outside of some health care settings?) How far do you have to go to find an institution, profit or non-profit, doing the same?

How about allowing a members’ vote on this? Or should I just be happy that the AEA is making itself irrelevant at such a rapid pace? It is remarkable the speed at which the economics profession isn’t really about economics any more.

For the pointer here I thank MS.

Water problems in Jackson, Mississippi

I am now reading quite a few analyses of the problem, and so few mention price! Even when written by economists. I find this article somewhat useful:

“We are a city with very high levels of poverty, and it’s difficult for us to raise the rates enough to do large scale replacement type projects and not make it unaffordable to live in the city of Jackson,” said former city councilman Melvin Priester Jr.

Yet the cost of Jackson’s poor quality water is still passed on to families who don’t trust the tap and purchase bottled water — which can cost a family of four $50-$100 a month — to drink instead.

The city raised water rates in 2013, but the Siemens deal penned the same year came with an onslaught of problems, including the installation of faulty water meters and meters that measured water in gallons instead of the correct cubic feet. This made any benefits of the rate increase virtually impossible to see.

The results have been nonsensical. Over the past several years, the city has mailed exorbitant bills to some customers and none to others. Sometimes, the charges weren’t based on how much water a household used and other times, city officials advised residents to “pay what they think they owe.” Past officials said the city lacked the manpower and expertise in the billing department to manually rectify the account issues with any speed.

In trying to protect people during the persistent billing blunders, the city has at times instituted no-shutoff policies, which demonstrate compassion but haven’t helped to compel payment.

Today, more than 8,000 customers, or nearly one-sixth of the city’s customer base, still aren’t receiving bills. Nearly 16,000 customers owe more than $100 or are more than 90 days past due, a city spokesperson told Mississippi Today. Jackson water customers owe a total of $90.3 million.

As a result, the city continues to miss out on tens of millions of water revenues. In 2016, when officials first uncovered the issue, the city’s actual water sewer collections during the previous year was a startling 32% less than projected — a roughly $26 million shortfall.

And most generally:

“The nature of local politics is that city governments will tend to neglect utilities until they break because they’re literally buried,” he said. “One of the things that is a perennial challenge for governments that operate water systems is that the quality of the water system is very hard for people to observe. But the price is very easy for them to observe.”

From WSJ here is some important background information:

Unlike bridges, roads and subway lines, clean drinking water isn’t primarily funded by taxes. More than 90% of the average utility’s revenues come directly from constituents’ water bills.

In other words, the price is too low, and government failure is the reason why. A higher price is no fun for a relatively poor set of Jackson buyers, but the city’s per capita income is 22k or so, and plenty of countries in that income range have satisfactory water systems where you can shower without closing your mouth. You just have to get the institutions and incentives right. It is remarkable to me how few people in the public sphere are making theses relatively straightforward points.

Trade Adjustment Assistance might be going away

The program that Mr. Ogg looked to for help, known as Trade Adjustment Assistance, has for the past 60 years been America’s main antidote to the pressures that globalization has unleashed on its workers. [TC’s aside: this first sentence is quite false.] More than five million workers have participated in the program.

But a lack of congressional funding has put the program in jeopardy: Trade assistance was officially terminated on July 1, though it continues to temporarily serve current enrollees. Unless Congress approves new money for the $700 million program, it will cease to exist entirely.

And:

Some academic research has found benefits for those who enrolled in the program. Workers gave up about $10,000 in income while training, but 10 years later they had about $50,000 higher cumulative earnings than those who did not retrain, according to research from 2018 by Benjamin G. Hyman, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Still, those relative gains decayed over time, Mr. Hyman’s research shows. After 10 years the incomes of those who received assistance and those who did not were the same…

Here is the full NYT article. With the China shock largely behind us, perhaps phasing this out is the right thing to do?

The Cream Rises to the Top

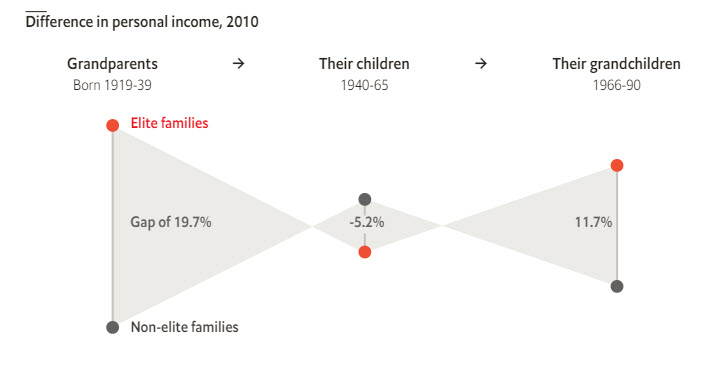

NBER: Can efforts to eradicate inequality in wealth and education eliminate intergenerational persistence of socioeconomic status? The Chinese Communist Revolution and Cultural Revolution aimed to do exactly that. Using newly digitized archival records and contemporary census and household survey data, we show that the revolutions were effective in homogenizing the population economically in the short run. However, the pattern of inequality that characterized the pre-revolution generation re-emerges today. Almost half a century after the revolutions, individuals whose grandparents belonged to the pre-revolution elite earn 16 percent more income and have completed more than 11 percent additional years of schooling than those from non-elite households. We find evidence that human capital (such as knowledge, skills, and values) has been transmitted within the families, and the social capital embodied in kinship networks has survived the revolutions. These channels allow the pre-revolution elite to rebound after the revolutions, and their socioeconomic status persists despite one of the most aggressive attempts to eliminate differences in the population.

That’s the abstract of Persistence Despite Revolutions one of Alberto Alesina’s last papers (with

Hat tip: The excellent Stefan Schubert.

From the comments, from Susan Dynarski on debt forgiveness

Here is the link, to my post on the educational returns to the marginal student. Please go back and read that for the context on Dynarski’s statement.

And from an email from David J. Deming, Harvard researcher in the area:

Sue is right that community college attendance is more common for students below the threshold in the Zimmerman paper. But many of them also attend no college at all. Table 4 shows that making the GPA cutoff increases years of 4 year college attendance by 0.46 and decreases years of community college attendance by 0.17. This implies that there is an increase in total college attendance – so the counterfactual is a mix of 2-year college and no college.

On the substance of the comment “do these people need debt forgiveness”? I’d say that ex ante they do not, but maybe some should receive it ex post. The Zimmerman estimate captures ex ante returns. Debt forgiveness is ex post. FIU’s grad rate was around 50% at that time, so the average return of 22% includes graduates and dropouts together. Ex post returns could be 44% for graduates and zero for dropouts.

Your idea of limiting debt forgiveness to dropouts was great. I wish that had been on the table. We’d worry about moral hazard if it became a forward-looking policy, but the Biden policy was probably not foreseeable in advance.

I would have also liked to see debt forgiveness focused on institutions rather than students. Forgive debt obtained at low-quality for-profit colleges. I would actually guess that college quality is a better predictor of lifetime wealth than current income. A person making $50k as a working adult 2 years after dropping out of University of Phoenix surely has lower expected lifetime wealth than a person who graduated from Harvard a few years ago and is making $50k in a public sector job.

My view is that decent returns to the marginal student still create problems for the Dynarski debt forgiveness argument. Overall the private returns to education are good. You can pack some of the problems into specific subgroups, but to the extent you do that the case for more debt relief targeting — much more targeting — rises rather steeply and rapidly.

Cost-Benefit Analysis of the TSA

A nice opening anecdote on life at the TSA from the Verge:

People cry at airports all the time. So when Jai Cooper heard sobbing from the back of the security line, it didn’t really faze her. As an officer of the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), she had gotten used to the strange behavior of passengers. Her job was to check people’s travel documents, not their emotional well-being.

But this particular group of tearful passengers presented her with a problem. One of them was in a wheelchair, bent over with her head between her knees, completely unresponsive. “Is she okay? Can she sit up?” Cooper asked, taking their boarding passes and IDs to check. “I need to see her face to identify her.”

“She can’t, she can’t, she can’t,” said the passenger who was pushing the wheelchair.

Soon, Cooper was joined at her station by a supervisor, followed by an assortment of EMTs and airport police officers. The passenger was dead. She and her family had arrived several hours prior, per the airport’s guidance for international flights, but she died sometime after check-in. Since they had her boarding pass in hand, the distraught family figured that they would still try to get her on the flight. Better that than leave her in a foreign country’s medical system, they figured.

The family might not have known it, but they had run into one of air travel’s many gray areas. Without a formal death certificate, the passenger could not be considered legally dead. And US law obligates airlines to accommodate their ticketed and checked-in passengers, even if they have “a physical or mental impairment that, on a permanent or temporary basis, substantially limits one or more major life activities.” In short: she could still fly. But not before her body got checked for contraband, weapons, or explosives. And since the TSA’s body scanners can only be used on people who can stand up, the corpse would have to be manually patted down.

“We’re just following TSA protocol,” Cooper explained.

Her colleagues checked the corpse according to the official pat-down process. With gloves on, they ran the palms of their hands over the collar, the abdomen, the inside of the waistband, and the lower legs. Then, they checked the body’s “sensitive areas” — the breasts, inner thighs, and buttocks — with “sufficient pressure to ensure detection.”

Only then was the corpse cleared to proceed into the secure part of the terminal.

Not even death can exempt you from TSA screening.

Later we get to the economics:

Actuaries measure the cost-effectiveness of an intervention — say, a pharmaceutical drug or a safety device like a seat belt — with a metric called “cost per life saved.” This calculation tries to capture the total societal net resources spent in order to save one year of life. For example, mandatory seat belt laws cost $138; railway crossing gates cost $90,000; and inpatient intensive care at a hospital can cost up to $1 million per visit. As long as an intervention costs less than $10 million per life saved, government agencies are generally happy to back them.

The most generous independent estimates of the cost-effectiveness of the TSA’s airport security screening put the cost per life saved at around $15 million. And that makes two big assumptions: first, that the agency is both 100 percent effective and 100 percent responsible for stopping all terror attacks; and second, that it stops an attack on the scale of 9/11 about once a decade. Less optimistic assessments place the number at $667 million per life saved.

The temporary popularity of Caplanian views on higher education

Bryan Caplan as you know argues that even the private return to higher education isn’t what it usually is cracked up to be, especially since large numbers of individuals do not finish with a four-year degree. Susan Dynarski (tenured at Harvard education, but an economist), writing in the NYT, seems to have started flirting with this view:

…a majority of people holding student debt have moderate incomes and low balances. Many have no degree, having dropped out of a public college or for-profit vocational school after a few semesters. They carry little debt, but they also do not get the benefit of a college degree to help them pay off that debt.

Defaults and financial distress are concentrated among the millions of students who drop out without a degree. The financial prospects for college dropouts are poor; they earn little more than do workers with no college education. Dropouts account for much of the increase in financial distress among student borrowers since the Great Recession.

And dropout is not at all rare. A bit less than half of college students don’t earn a bachelor’s degree. Some people earn a shorter, two-year associate degree. But more than a quarter of those who start college hoping to earn a degree drop out with no credential. A full 30 percent of first-generation freshmen drop out of four-year colleges within three years. That’s three times the dropout rate of students whose parents graduated from college.

I’ve seen modest variants on those numbers, but the general picture is broadly accepted. Now here is Dynarski’s Congressional testimony from last summer:

College is a Great Investment

A college education is a great investment. Over a lifetime, a person with a bachelor’s degree will earn, on average, a million dollars more than a less-educated worker. Even with record-high tuition prices, a BA pays for itself several times over.

She is quite clear in the former NYT piece that she has changed her mind, so there is no “gotcha” here. But clearly her views are evolving in Bryan’s direction.

In terms of policy, Dynarski notes that more than a quarter drop out of college with no credential. Shouldn’t we restrict loan forgiveness to them? Doesn’t that at least deserve discussion? Or should we just go ahead and grant forgiveness to those with the “great” returns as well? Her change of mind concerns the higher-than-expected problems of the non-finishers, not that she has seen new and inferior income numbers for the successes. (In fact since the numbers for the average return haven’t changed, being more pessimistic about the losers has to mean being a bit more optimistic about the successes. That should make us all the more interested in targeting the forgiveness.)

Why are we not allowed to know what percentage of the forgiveness beneficiaries fall into the “didn’t finish” category? What should we infer from the reality that no one is reporting that statistic? Is that good news or bad news for the policy?

What does Dynarski think is the marginal return from trying to finish college? Are they really so positive for the marginal student? What is the chance of the marginal student finishing? The cited figures are averages, presumably for the marginal student the chance of finishing is much worse. Presumably she is pessimistic about the nature of the college deal for the marginal student?

Now I know how these discussions run. Suddenly there is plenty of talk about how we should make it easier for people to finish, perhaps by offering more aid. As someone who teaches at a non-elite state university, I do understand what is going on with students who need to drop out to take care of family, and so on. Still, in the meantime should we be encouraging more marginal students to try their hand at college?

Yes or no?

That question runs against the prevailing mood affiliation and good luck trying to get a straight answer. In the meantime, the world is taking an ever-so-temporary foray into the views of Bryan Caplan. Let’s see how long it stays there.

The Price of Power and the Power of Prices

As Europe’s energy crisis intensifies we are seeing calls for price caps, rationing, and command and control.

What’s happening: A range of government-imposed restrictions, akin to the kind of restraints during wartime, here is a sampling.

In Germany:

- Cologne’s magnificent cathedral — normally lit throughout the night — now goes dark over night. Public buildings, museums and other landmarks — such as the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin — will no longer be illuminated overnight either.

- In Hanover last month, hot water was cut off at public buildings, as the city seeks to cut consumption by 15%.

- The southern city of Augsburg decided to turn off traffic lights.

Spain:

- Congress agreed to temperature limitations — air conditioning no cooler than 27 degrees Celsius, or nearly 81 degrees Fahrenheit.

- After 10 p.m. shop windows and unoccupied public buildings won’t be lit.

Italy:

- Air conditioning in schools and public buildings has already been limited in what the government labeled “Operation Thermostat,” starting in May.

France:

- Shopkeepers will now be fined for keeping doors open and air conditioning running, a common practice.

- Illuminated signs will be banned between 1 a.m. and 6 a.m.

The Economist, however, reminds us of the power of prices. Namely, price caps can backfire but price increases can be combined with cash transfers can protect vulnerable consumers while maintaining strong incentives to reduce consumption and find substitutes:

How households respond to enormous price shocks has rarely been studied, owing to a lack of real-world data. One exception is that produced by Ukraine, which Anna Alberini of the University of Maryland and co-authors have studied, looking at price rises in 2015 after subsidies were cut. They found that among households that did not invest in better heating or insulation a doubling of prices led to a 16% decline in consumption.

Policies to help households cope with high prices have also been studied—and the results are bad news for politicians capping prices. In California, where a government programme cut the marginal price of gas for poor households by 20%, households raised their consumption by 8.5% over the next year to 18 months. Ukraine has found a better way to help. Households struggling to pay their bills can apply for a cash transfer. Since such a transfer is unrelated to consumption, it preserves the incentive for shorter showers, and thus does not blunt the effect of high prices on gas use. Another option is a halfway house between a price cap and a transfer. An Austrian state recently introduced a discount on the first 80% of a typical household’s consumption, which means people retain an incentive to cut back on anything over that.

…Households are not the only consumers of gas. Early in the war, manufacturers and agricultural producers argued against doing anything that might risk supplies, since production processes took time to alter and output losses could cascade through the economy. But initial evidence from the German dairy and fertiliser industries suggests that even heavy users respond to higher prices. Farmers have switched from gas to oil heating; ammonia, fertiliser’s gas-intensive ingredient, is now imported instead of being made locally.

Over time, households and industry will adapt more to higher prices, meaning that with every passing month demand for gas will fall.

The power of prices reminds us that carbon taxes can be effective at surprising low cost if we give them a chance to operate.

Indonesia is doing OK

The rupiah, down only 3.8%, is the third best-performing Asian currency this year. It’s all the more remarkable considering Bank Indonesia has resisted following the Fed and only began raising interest rates this week, by a modest 25 basis points.

Its stock market is another winner. The iShares MSCI Indonesia ETF is up 5.6% this year, beating the S&P 500 Index’s 13.1% drop. As a result, even though foreigners have been selling holdings of government bonds, robust equity demand has helped stabilize Indonesia’s portfolio flows…

The conflict in Ukraine has pushed up prices of palm oil and coal, which Indonesia exports. These two commodities alone improved the country’s current account by 2.4% of its gross domestic product since 2019, with one-third coming from palm oil and the rest from elevated coal prices, according to HSBC Holdings Plc. Indonesia now has a solid current-account surplus for the first time since 2011.

Here is more from Shuli Ren of Bloomberg.

The Student Loan Giveaway is Much Bigger Than You Think

Wiping out 10k in student debt is not the most expensive part of the Biden student loan program. Most Federal student loans are now eligible for an income based repayment plan, under these plans students pay a small percentage of their “discretionary” income, say 10%, and then after a fixed number of years the debt is wiped off the student’s books. At first glance these plans don’t seem crazy, but as Matt Bruenig points out they create perverse incentives.

Under the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program, law graduates that go on to work in the public sector, which is a lot of them as the public sector employs many lawyers, only have to pay 10 percent of their discretionary income for 10 years in order to have their debt forgiven.

Law schools figured out many years ago that, for a student who is planning to enroll in PSLF upon graduation, prices and debt loads don’t matter. Ten percent of your discretionary income is ten percent of your discretionary income regardless of what the law school charges you and how much debt you nominally have to take on.

Law schools also realized that they could make the deal even sweeter by setting up LRAPs [repayment programs, AT] that give graduates money to cover the the modest repayments required by the PSLF.

The LRAP schemes work as follows:

- The school increases their tuition.

- The student takes out federal loans to cover the tuition increase.

- The school squirrels away the debt-financed tuition increase into an LRAP fund.

- The school disburses money from the LRAP fund to cover PSLF repayments.

Did you get that? Here’s a stylized example. Suppose a student will make 150k per year for 10 years working in the public sector. If they have 200k in debt they pay 15k every year to the government for 10 years and then 50k is “forgiven.” But now the law school comes to the student and says ‘heh, I have a deal which will make both of us better off. We are going to raise the price of law school to 400k but don’t worry not only won’t that cost you a penny more than the 15k a year you are already obligated to pay it will actually cost you much less because we will pay your payments of 15k per year!’ This indeed is a great deal for the student who pays nothing and it’s a great deal for the law school which gets 200k more revenue immediately in return for 150k of payments paid out over the following 10 years. Win-win! Except for the taxpayer of course.

But wait there’s more. Student loans can be used not only to pay tuition and fees but also to pay “living expenses.” Thus, under these plans, students have an incentive to take out as big a loan as allowed in excess of tuition and fees because no matter how large the loan the student’s costs are zero! Lyman Stone has a good tweet thread giving many examples of how to game the system such as “Every student should borrow their maximum loan eligibility and then find some way to invest it illegally. My strategy would be: rent a wildly oversized apartment and sublet.” And here is a tweet thread from Michael Feinberg showing how even wealthy parents may be able to game the system.

Furthermore, the new Biden plan makes the income driven repayment schemes even more generous!

The IDR changes are four-fold:

- Increase the amount of income not subject to IDR from 150 percent of the federal poverty line to 225 percent of the federal poverty line.

- Reduce the interest rate on IDR-enrolled loans to 0 percent.

- For undergraduate debt, reduce the IDR rate from 10 percent of income beyond the threshold in (1) to 5 percent of income beyond the threshold in (1).

- For IDR-enrolled debts with original loan balances below $12,000, reduce the repayment period from 20 years to 10 years.

Essentially what this means is that every school will now have the possibility of using a law school like program to shift costs onto taxpayers. Thus Bruenig concludes:

…going forward, these new rules could quite radically alter the incentives of colleges and students when it comes to college prices, institutional financial aid, how much debt to take on, and how to approach repayment.

Indeed, these programs are likely to be very expensive and the resulting increase in the price of tuition will lead to calls either to end the program or for price controls on education.

Kin-based institutions and economic development

Though many theories have been advanced to account for global differences in economic prosperity, little attention has been paid to the oldest and most fundamental of human institutions: kin-based institutions—the set of social norms governing descent, marriage, clan membership, post-marital residence and family organization. Here, focusing on an anthropologically well established dimension of kinship, we establish a robust and economically significant negative association between the tightness and breadth of kin-based institutions—their kinship intensity—and economic development. To measure kinship intensity and economic development, we deploy both quantified ethnographic observations on kinship and genotypic measures (which proxy endogamous marriage patterns) with data on satellite nighttime luminosity and regional GDP. Our results are robust to controlling for a suite of geographic and cultural variables and hold across countries, within countries at both the regional and ethnolinguistic levels, and within countries in a spatial regression discontinuity analysis. Considering potential mechanisms, we discuss evidence consistent with kinship intensity indirectly impacting economic development via its effects on the division of labor, cultural psychology, institutions, and innovation.

That is a new and very important paper by Duman Bahrami-Rad, Jonathan Beauchamp, Joseph Henrich, and Jonathan Schulz, the two Jonathans being my colleagues at GMU.