Category: Food and Drink

Politically Incorrect Paper of the Day: The United Fruit Company was Good!

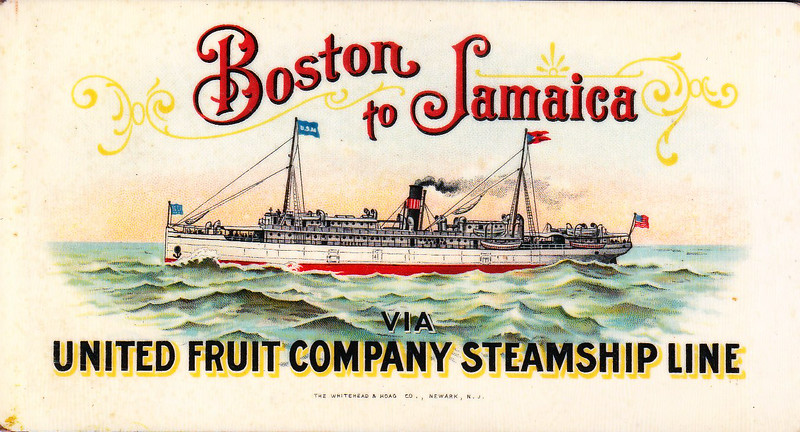

The United Fruit Company is the bogeyman of Latin America, the very apotheosis of neo-colonialism. And to be sure in the UFC history there is wrongdoing and plenty of fodder for conspiracy theories but the UFC also brought bananas (as export crop), tourism, and in many cases good governance to parts of Latin America. Much, however, depends on the institutional constraints within which the company operated. Esteban Mendez-Chacon and Diana Van Patten (on the job market) look at the UFC in Costa Rica.

The UFC needed to bring workers to remote locations and thus it invested heavily in worker welfare:

…the UFC invested in sanitation infrastructure, launched health programs, and provided medical attention to its employees. Infrastructure investments included pipes, drinking water systems, sewage system, street lighting, macadamized roads, a dike (Sanou and Quesada, 1998), and by 1942 the company operated three hospitals in the country.

… Given the remoteness the plantations and to reduce transportation costs, the UFC provided the majority of its workers with free housing within the company’s land. This was partially motivated by concerns with diseases like malaria and yellow fever, which spread easily if the population is constantly commuting from outside the plantation. By 1958 the majority of laborers lived in barracks-type structures… [which] exceeded the standards of many surrounding communities (Wiley, 2008).

The UFC wasn’t just interested in healthy workers, they also needed to attract workers with stable families:

The UFC wasn’t just interested in healthy workers, they also needed to attract workers with stable families:

… One of the services that the company provided within its camps was primary education to the children of its employees. The curriculum in the schools included vocational training and before the 1940s, was taught mostly in English. The emphasis on primary education was significant, and child labor became uncommon in the banana regions (Viales, 1998). By 1955, the company had constructed 62 primary schools within its landholdings in Costa Rica (May and Lasso, 1958). As shown in Figure 6a,spending per student in schools operated by the UFC was consistently higher than public spending in primary education between 1947 and 1963.21 On average, the company’s yearly spending was 23% higher than the government’s spending during this period.

…The UFC did not provide directly secondary education although offered some incentives. If the parents could afford the first two years of secondary education of their children in the United States, the UFC paid for the last two years and provided free transportation to and from the United States.

A key driver of UFC investment was that although the UFC was the sole employer within the regions in which it operated, it had to compete to obtain labor from other regions. Thus a 1925 UFC report writes:

We recommend a greater investment in corporate welfare beyond medical measures. An endeavor should be made to stabilize the population…we must not only build and maintain attractive and comfortable camps, but we must also provide measures for taking care of families of married men, by furnishing them with garden facilities, schools, and some forms of entertainment. In other words, we must take an interest in our people if we might hope to retain their services indefinitely.

This is exactly the dynamic which drove the provision of services and infrastructure in unjustly maligned US company towns. It’s also exactly what Rajagopalan and I found in the Indian company town of Jamshedpur, built by Jamshetji Nusserwanji Tata.

The UFC ended in Costa Rica in 1984 but the authors find that it had a long-term positive impact. Using historical records, the authors discover a plausibly randomly-determined boundary line between UFC and non-UFC areas and comparing living standards just inside and just outside the boundary they find that households within the boundary today have better housing, sanitary conditions, education and consumption than households just outside the boundary. Overall:

We find that the firm had a positive and persistent effect on living standards. Regions within the UFC were 26% less likely to be poor in 1973 than nearby counterfactual locations, with only 63% of the gap closing over the following 3 decades.

The paper has appendixes A-J. In one appendix (!), they show using satellite data that regions within the boundary are more luminous at night than those just outside the region. The collection of data is especially notable:

For a better understanding of living standards and investments during UFC’s tenure, we collected and digitized UFC reports with data on wages, number of employees, production, and investments in areas such as education, housing, and health from collections held by Cornell University, University of Kansas, and the Center for Central American Historical Studies. We also use annual reports from the Medical Department of the UFC describing the sanitation and health programs and spending per patient in company-run hospitals from 1912 to 1931. We also collected data from Costa Rican Statistic Yearbooks, which from 1907 to 1917 contain details on the number of patients and health expenses carried out by hospitals in Costa Rica, including the ones ran by the UFC. Export data was also collected from these yearbooks, and from Export Bulletins. 19 agricultural censuses taken between 1900 and 1984 provide information on land use, and we use data from Costa Rican censuses between 1864-1963 to analyze aggregated population patterns, such as migration before and during the UFC apogee, or the size and occupation of the country’s labor force.

Overall, a tremendous paper.

Model this dopamine fast

“We’re addicted to dopamine,” said James Sinka, who of the three fellows is the most exuberant about their new practice. “And because we’re getting so much of it all the time, we end up just wanting more and more, so activities that used to be pleasurable now aren’t. Frequent stimulation of dopamine gets the brain’s baseline higher.”

There is a growing dopamine-avoidance community in town and the concept has quickly captivated the media.

Dr. Cameron Sepah is a start-up investor, professor at UCSF Medical School and dopamine faster. He uses the fasting as a technique in clinical practice with his clients, especially, he said, tech workers and venture capitalists.

The name — dopamine fasting — is a bit of a misnomer. It’s more of a stimulation fast. But the name works well enough, Dr. Sepah said.

The purpose is so that subsequent pleasures are all the more potent and meaningful.

“Any kind of fasting exists on a spectrum,” Mr. Sinka said as he slowly moved through sun salutations, careful not to get his heart racing too much, already worried he was talking too much that morning.

Here is more from Nellie Bowles at the NYT.

Learning is Caring: An Agrarian Origin of American Individualism

I am looking forward to reading this one, from Itzchak Tzachi Raz, who is on the job market from Harvard this year:

This study examines the historical origins of American individualism. I test the hypothesis that local heterogeneity of the physical environment limited the ability of farmers on the American frontier to learn from their successful neighbors, turning them into self-reliant and individualistic people. Consistent with this hypothesis, I find that current residents of counties with higher agrarian heterogeneity are more culturally individualistic, less religious, and have weaker family ties. They are also more likely to support economically progressive policies, to have positive attitudes toward immigrants, and to identify with the Democratic Party. Similarly, counties with higher environmental heterogeneity had higher taxes and a higher provision of public institutions during the 19th century. This pattern is consistent with the substitutability of formal and informal institutions as means to solve collective action problems, and with the association between “communal” values and conservative policies. These findings also suggest that, while understudied, social learning is an important determinant of individualism.

Here is the home page, the paper is not yet available. Here is his actual job market paper, on adverse possession. I do hope the author lets me know once this paper is ready, I am very much looking forward to reading it.

Can you impose pecuniary externalities upon Korean squirrels?

Look out, squirrels of the world. It turns out acorns are good for humans, too.

Here in South Korea, the popularity of acorn noodles, jelly and powder has exploded in recent years, after researchers declared the nuts a healthy “superfood” that can help fight obesity and diabetes.

In the U.S., where some Native Americans once made acorns a staple of their diet, restaurants and health-conscious blogs are starting to explore recipes for acorn crackers, acorn bread and acorn coffee.

That is bad news for squirrels and other animals that rely on oak trees for sustenance. In South Korea, where human foraging has multiplied, there are now fewer acorns on the ground, and the squirrel population has dwindled.

Is this a reductio ad absurdum of the idea that pecuniary externalities are irrelevant? Ask your friendly neighborhood squirrel! If you can find him, that is. Then there is this:

Safeguarding acorns for squirrels is proving to be a tough nut to crack. That’s where the Acorn Rangers come in.

Formed at Seoul’s Yonsei University, the nascent Acorn Rangers group polices the bucolic campus, scaring off other humans from swiping squirrel food. Taking up the cause are students like Park Ji-eun, who skipped lunch on a recent day so a squirrel could eat this winter.

Strolling across campus, Ms. Park, a junior, sprung into action after spotting an acorn assailant: a woman in her early 60s, clutching a plastic bag stuffed with the tree nuts.

“The squirrels will starve!” barked Ms. Park, her voice booming so loudly that other acorn hunters—human ones—scurried away. The two argued for nearly an hour until Ms. Park emerged with the plastic bag in hand.

Here is the full WSJ story, by Dasl Yoon and Na-Young Kim, via the excellent Samir Varma.

My Conversation with Ben Westhoff

Truly an excellent episode, Ben is an author and journalist. Here is the audio and transcript, covering most of all the opioid epidemic and rap music, but not only.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: But if so much fentanyl comes from China, and you can just send it through the mail, why doesn’t it spread automatically wherever it’s going to go? Is it some kind of recommender network? It wouldn’t seem that it’s a supply constraint. It’s more like someone told you about a restaurant they ate at last night.

WESTHOFF: It’s because the Mexican cartels are still really strongly in the trade. Even though it’s all made in China, much of it is trafficked through the cartels, who buy the precursors, the fentanyl ingredients, from China, make it the rest of the way. Then they send it through the border into the US.

You can get fentanyl in the mail from China, and many people do. It comes right to your door through the US Postal Service. But it takes a certain level of sophistication with the drug dealers to pull that off.

COWEN: It’s such a big life decision, and it’s shaped by this very small cost of getting a package from New Hampshire to Florida. What should we infer about human nature as a result of that? What’s your model of the human beings doing this stuff if those geographic differences really make the difference for whether or not you do this and destroy your life?

WESTHOFF: Well, everything is local, right? Not just politics. You’re influenced by the people around you and the relative costs. In St. Louis, it’s so incredibly cheap, like $5 to get some heroin, some fentanyl. I don’t know how it works in, say, New Hampshire, but I know in places like West Virginia, it’s still a primarily pill market. People don’t use powdered heroin, for example. For whatever reason, they prefer Oxycontin. So that has affected the market, too.

And:

COWEN: Did New Zealand do the right thing, legalizing so many synthetic drugs in 2013?

WESTHOFF: I absolutely think they did. It was an unprecedented thing. Now drugs like marijuana, cocaine, heroin, all the drugs you’ve heard of, are internationally banned. But what New Zealand did was it legalized these forms of synthetic marijuana. So synthetic marijuana has a really bad reputation. It goes by names like K2 and Spice, and it’s big in homeless populations. It’s causing huge problems in places like DC.

But if you make synthetic marijuana right, as this character in my book named Matt Bowden was doing in New Zealand, you can actually make it so it’s less toxic, so it’s somewhat safe. That’s what he did. They legalized these safer forms of it, and the overdose rate plummeted. Very shortly thereafter, however, they banned them again, and now deaths from synthetic marijuana in New Zealand have gone way up.

COWEN: And what about Portugal and Slovenia — their experiments in decriminalization? How have those gone?

WESTHOFF: By all accounts, they’ve been massive successes. Portugal had this huge problem with heroin, talking like one out of every 100 members of the population was touched by it, or something like that. And now those rates have gone way down.

In Slovenia, they have no fentanyl problem. They barely have an opioid problem. Their rates of AIDS and other diseases passed through needles have gone way down.

And on rap music:

COWEN: This question is maybe a little difficult to explain, but wherein lies the musical talent of hip-hop? If we look at Mozart, there’s melody, there’s harmony. If you listen to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, it’s something very specifically rhythmic, and the textures, and the organization of the blocks of sound. The poetry aside, what is it musically that accounts for the talent in rap music?

WESTHOFF: First of all, riding a beat, rapping, if you will, is extremely hard, and anyone who’s ever tried to do it will tell you. You have to have the right cadence. You have to have the right breath control, and it’s a talent. There’s also — this might sound trivial, but picking the right music to rap over.

So hip-hop, of course, is a genre that’s made up of other genres. In the beginning, it was disco records that people used. And then jazz, and then on and on. Rock records have been rapped over, even. But what song are you going to pick to use? And if someone has a good ear for a sound that goes with their style, that’s something you can’t teach.

And yes on overrated vs. underrated, you get Taylor Swift, Clint Eastwood, and Seinfeld, among others. I highly recommend all of Ben’s books, but most of all his latest one Fentanyl, Inc.: How Rogue Chemists Are Creating the Deadliest Wave of the Opioid Epidemic.

My Conversation with Alain Bertaud

Excellent throughout, Alain put on an amazing performance for the live audience at the top floor of the Observatory at the old World Trade Center site. Here is the audio and transcript, most of all we talked about cities. Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Will America create any new cities in the next century? Or are we just done?

BERTAUD: Cities need a good location. This is a debate I had with Paul Romer when he was interested in charter cities. He had decided that he could create 50 charter cities around the world. And my reaction — maybe I’m wrong — but my reaction is that there are not 50 very good locations for cities around the world. There are not many left. Maybe with Belt and Road, maybe the opening of Central Asia. Maybe the opening of the ocean route on the northern, following the pole, will create the potential for new cities.

But cities like Singapore, Malacca, Mumbai are there for a good reason. And I don’t think there’s that many very good locations.

COWEN: Or Greenland, right?

[laughter]

BERTAUD: Yes. Yes, yes.

COWEN: What is your favorite movie about a city? You mentioned a work of fiction. Movie — I’ll nominate Escape from New York.

[laughter]

BERTAUD: Casablanca.

Here is more:

COWEN: Your own background, coming from Marseille rather than from Paris —

BERTAUD: I would not brag about it normally.

[laughter]

COWEN: But no, maybe you should brag about it. How has that changed how you understand cities?

BERTAUD: I’m very tolerant of messy cities.

COWEN: Messy cities.

BERTAUD: Yes.

COWEN: Why might that be, coming from Marseille?

BERTAUD: When we were schoolchildren in Marseille, we were used to a city which has a . . . There’s only one big avenue. The rest are streets which were created locally. You know, the vernacular architecture.

In our geography book, we had this map of Manhattan. Our first reaction was, the people in Manhattan must have a hard time finding their way because all the streets are exactly the same.

[laughter]

BERTAUD: In Marseille we oriented ourselves by the angle that a street made with another. Some were very narrow, some very, very wide. One not so wide. But some were curved, some were . . . And that’s the way we oriented ourselves. We thought Manhattan must be a terrible place. We must be lost all the time.

Finally:

COWEN: And what’s your best Le Corbusier story?

BERTAUD: I met Le Corbusier at a conference in Paris twice. Two conferences. At the time, he was at the top of his fame, and he started the conference by saying, “People ask me all the time, what do you think? How do you feel being the most well-known architect in the world?” He was not a very modest man.

[laughter]

BERTAUD: And he said, “You know what it feels? It feels that my ass has been kicked all my life.” That’s the way he started this. He was a very bitter man in spite of his success, and I think that his bitterness is shown in his planning and some of his architecture.

COWEN: Port-au-Prince, Haiti — overrated or underrated?

Strongly recommended, and note that Bertaud is eighty years old and just coming off a major course of chemotherapy, a remarkable performance.

Again, I am very happy to recommend Alain’s superb book Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities.

Dining out in Karachi

The general standard is very high, though trying to chase after “the best place” does not seem worth the effort — it is more about choosing the best dish to order. As in India, the hotel restaurants are excellent, and you can sample everything you might want without leaving a single restaurant, if you find the dust and heat too daunting (I do not, but you might, please do believe me on that one). The crowning glories in Karachi are the biryanis and the lassi. A randomly chosen lassi here seems to match the very best Indian lassis in quality. The karahi dishes come alive like nowhere else. Qorma sauces too. Vegetables are hard to come by, especially greens — the restaurant version of Karachi cuisine is quite meat-heavy, and the overall selection of dishes is not so different from what you find in the Pakistani restaurants in Springfield, Virginia. That said, the greens and herbs that accompany the meat dishes are fresh and vibrant.

One secondary consequence of the meat emphasis is that Karachi Western fast food is much more like the Western version than you might find in India. Hamburgers carry over very well to the Pakistani context, as does slopping together meat and bread in various ways, a’ la Subway. There is Movenpick chocolate ice cream in various shopping malls and hotels. Reasonable Chinese food can be found, can you say “One Belt, One Road”?

Golub Jamun, typically an atrocity in the United States, is marvelous in Pakistan.

Canadian markets in everything but they need a British person too

One brave outdoorsman will finally take a special shot of whiskey at a bar in Canada’s Yukon Territory containing his amputated, now-dehydrated big toe, which he donated to the establishment for their signature “Sourtoe Cocktail” after losing it to frostbite in February 2018.

Nick Griffiths of Greater Manchester, England, lost three toes to frostbite while competing in the intense Yukon Arctic Race two winters ago.

That is not even the strangest part of the story. Via the excellent Samir Varma.

My favorite things Pakistan

1. Female singer: Abida Parveen, here is one early song, the later material is often more commercial. Sufi songs!

2. Qawwali performers: Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, the Sabri Brothers, and try this French collection of Qawwali music.

3. Author/novel: Daniyal Mueenuddin, In Other Rooms, Other Wonders. I am not sure why this book isn’t better known. It is better than even the average of the better half of the Booker Prize winners. Why doesn’t he write more?

4. Dish: Haleem: “Haleem is made of wheat, barley, meat (usually minced beef or mutton (goat meat or Lamb and mutton) or chicken), lentils and spices, sometimes rice is also used. This dish is slow cooked for seven to eight hours, which results in a paste-like consistency, blending the flavors of spices, meat, barley and wheat.”

5. Movie: I don’t think I have seen a Pakistani film, and my favorite movie set in Pakistan is not so clear. Charlie Wilson’s War bored me, and Zero Dark Thirty is OK. What am I forgetting?

6. Economic reformer: Manmohan Singh.

7. Economist: Atif Mian, born in Nigeria to a Pakistani family.

8. Textiles: Wedding carpets from Sindh?

9. Visual artist: Shahzia Shikhander, images here.

I don’t follow cricket, sorry!

Yak loose in Virginia after escaping transport to the butchers

A yak is on the loose in the US state of Virginia after escaping from a trailer on its way to the butchers.

Meteor, a three-year-old who belongs to farmer Robert Cissell of Nature’s Bridge Farm in Buckingham, Virginia, has been missing since Tuesday.

Mr Cissell told the BBC Meteor had been raised for meat and described the animal as “aloof”.

He said if captured the yak would “most likely live out his life here with our breeding herd”.

Kevin Wright, an animal control supervisor for Nelson County, said: “It broke through a stop sign and we’ve been trying to catch it for a while. It’s a well-mannered creature and clearly doesn’t want to be handled.”

…The animal was seen at a bed and breakfast in the county but is believed to have wandered to the mountains.

Here is the full story, via Michelle Dawson.

Corn markets in everything

Farmers across the U.S. have stumbled onto a fertile side hustle at a time when prices for their crops are low: cramming produce into an air gun and charging people to fire it into the sky.

Growers of corn, apples and even pumpkins place the agricultural ammo at the base of a long tube, sometimes with the help of a ramrod. Then they use an air compressor to build up enough pressure to send the fruits or vegetables flying hundreds of feet, where they land with a satisfying splat.

“Why not shoot it?” says Fred Howell, owner of Howell’s Pumpkin Patch in Cumming, Iowa. “We’re fat Americans and we play with our food.”

It’s a way to keep jaded teens and bored adults coming back to spend time and money on the farms while the youngest members of the family are happy petting sheep.

Here is the full WSJ story, via the excellent Samir Varma.

Karachi, Pakistan bleg

Guidebooks on Karachi, at least in English, are rather hard to come by. So what should I see and do, and where should I eat? I thank you all in advice for your usual sage counsel.

My Ethnic Dining Guide, 31st edition

Here is the link to the html edition, 127 pp. of text, useful throughout. The blog version is found at tylercowensethnicdiningguide.com, the two have basically the same content.

Mama Chang and Poca Madre, both reviewed near the top, are two of my new favorites of the last year.

What should I ask Ben Westhoff?

I will be doing a Conversation with him, no associated public event, here is from his home page:

Ben Westhoff is an award-winning investigative journalist who writes about culture, drugs, and poverty. His books are taught around the country and have been translated into languages all over the world.

His new book Fentanyl, Inc.: How Rogue Chemists Are Creating the Deadliest Wave of the Opioid Epidemic releases September 3, 2019 in the U.S. (Grove Atlantic) and October 10, 2019 in the UK, Austrailia, and New Zealand (Scribe). Here’s more information.

His previous book Original Gangstas: Tupac Shakur, Dr. Dre, Eazy-E, Ice Cube, and the Birth of West Coast Rap has received raves from Rolling Stone and People, a starred review in Kirkus, a five-star Amazon rating, and made numerous year-end best lists. More info can be found here.

…his 2011 book on southern hip-hop, Dirty South: OutKast, Lil Wayne, Soulja Boy, and the Southern Rappers Who Reinvented Hip-Hop was a Library Journal best seller.

Here is my review of his excellent forthcoming Fentanyl, Inc. He also has a well-acclaimed book on New York City bars and dives. All of his work is fascinating.

So what should I ask him?

My Conversation with Masha Gessen

Here is the transcript and audio, here is the summary:

Masha joined Tyler in New York City to answer his many questions about Russia: why was Soviet mathematics so good? What was it like meeting with Putin? Why are Russian friendships so intense? Are Russian women as strong as the stereotype suggests — and why do they all have the same few names? Is Russia more hostile to LGBT rights than other autocracies? Why did Garry Kasparov fail to make a dent in Russian politics? What did The Americans get right that Chernobyl missed? And what’s a good place to eat Russian food in Manhattan?

Here is excerpt:

COWEN: Why has Russia basically never been a free country?

GESSEN: Most countries have a history of never having been free countries until they become free countries.

[laughter]

COWEN: But Russia has been next to some semifree countries. It’s a European nation, right? It’s been a part of European intellectual life for many centuries, and yet, with the possible exception of parts of the ’90s, it seems it’s never come very close to being an ongoing democracy with some version of free speech. Why isn’t it like, say, Sweden?

GESSEN: [laughs] Why isn’t Russia like . . . I tend to read Russian history a little bit differently in the sense that I don’t think it’s a continuous history of unfreedom. I think that Russia was like a lot of other countries, a lot of empires, in being a tyranny up until the early 20th century. Then Russia had something that no other country has had, which is the longest totalitarian experiment in history. That’s a 20th-century phenomenon that has a very specific set of conditions.

I don’t read Russian history as this history of Russians always want a strong hand, which is a very traditional way of looking at it. I think that Russia, at breaking points when it could have developed a democracy or a semidemocracy, actually started this totalitarian experiment. And what we’re looking at now is the aftermath of the totalitarian experiment.

And:

GESSEN: …I thought Americans were absurd. They will say hello to you in the street for no reason. Yeah, I found them very unreasonably friendly.

I think that there’s a kind of grumpy and dark culture in Russia. Russians certainly have a lot of discernment in the fine shades of misery. If you ask a Russian how they are, they will not cheerfully respond by saying they’re great. If they’re miserable, they might actually share that with you in some detail.

There’s no shame in being miserable in Russia. There’s, in fact, a lot of validation. Read a Russian novel. You’ll find it all in there. We really are connoisseurs of depression.

Finally there was the segment starting with this:

COWEN: I have so many questions about Russia proper. Let me start with one. Why is it that Russians seem to purge their own friends so often? The standing joke being the Russian word for “friend” is “future enemy.” There’s a sense of loyalty cycles, where you have to reach a certain bar of being loyal or otherwise you’re purged.

Highly recommended.