Category: History

Micah Tillman defends Edmund Husserl

I allowed him three paragraphs, and he emails me the following:

Husserl was a mathematician whose desire to understand how (and why) mathematics actually works turned him into a philosopher of logic, science, language, and mind. Without the movement he inaugurated, Heidegger (and therefore everyone who followed Heidegger), Merleau-Ponty, Sartre, Levinas, and Derrida (and even John Paul II) would not have become the philosophers we know them as today.

Husserl was inspired by Hume and Kant, but believed both made a fundamental mistake. Empiricists like Hume became skeptics after concluding that all we truly know are our own sensations; we never experience the “real things” we think we do. Idealists like Kant essentially agreed (we experience only phenomena, never noumena) but believed that at least we could discover the universal rules of the human mind.

Husserl argued that the “things themselves” actually show up for us through our experiences and therefore we can learn about the real world through a study of the structures (patterns, types, and forms) of human experience. In the process, he reconciled empiricism and idealism. The empiricist insistence on experience over speculation is central to phenomenology, as is the idealist claim that the study of the mind is the path to knowledge of ultimate reality. With the combination of the two, every area of the world, and every part of life, became a subject for philosophical investigation, and philosophy experienced a kind of second birth.

Earlier I had named Husserl as “the worst philosopher.” But of course I am delighted to present a contrasting view. Micah is a professional philosopher and an adherent of phenomenology, his web page is here. His recently completed dissertation was “Empty and Filled Intentions in Husserl’s Early Work.” He describes the “things themselves” — in less than 140 characters — here.

Who is the worst philosopher?

That was one of the questions I was asked at my Jane St. Capital talk on Wednesday night.

My answer was Edmund Husserl, at least if we restrict the question to philosophers of renown. I believe his work is a waste of time and I write that as someone who does not believe Heidegger is a (total) waste of time, especially in the essays. As for Husserl, we can pull this bit off Wikipedia:

Therein, Husserl in 1931 refers to “Transcendental Subjectivity” being “a new field of experience” opened as a result of practicing phenomenological reduction, and giving rise to an a priori science not empirically based but somewhat similar to mathematics. By such practice the individual becomes the “transcendental Ego”, although Husserl acknowledges the problem of solipsism. Later he emphasizes “the necessary stressing of the difference between transcendental and psychological subjectivity, the repeated declaration that transcendental phenomenology is not in any sense psychology… ” but rather (in contrast to naturalistic psychology) by the phenomenological reduction “the life of the soul is made intelligible in its most intimate and originally intuitional essence” and whereby “objects of the most varied grades right up to the level of the objective world are there for the Ego… .” Ibid. at 5-7, 11-12, 18.

The Stanford Encyclopedia gives you more detail on his philosophy. Here is Husserl presented on YouTube, in his own words as they say.

I suggested both Aristotle and Nietzsche as overrated philosophers, although clearly both are still great philosophers, worthy of major reputations. But neither should be considered a real candidate for “greatest philosopher ever,” which is what you sometimes hear. I’ll reserve that for Plato and Hume.

From the comments

This is from Mark A. Sadowski, who makes some other good comments in the same thread:

Marcus Nunes’ post caused me to reread E. Cary Brown’s “Fiscal Policy in the “Thirties: A Reappraisal” (American Economic Review, Vol. 46, No. 5, December 1956, pp. 857–879) and Larry Peppers’ “Full Employment Surplus Analysis and Structural Changes” (Explorations in Economic History, Vol. 10, Winter 1973, pp. 197–210), both of which are mentioned in the Douglas A. Irwin’s paper on gold sterilization and the recession of 1937-38 which Marcus discusses in his excellent post.

Peppers’ paper shows how to calculate cyclically adjusted budget balances from Brown’s paper. By my arithmetic, according to Brown’s data the cyclically adjusted general government balance increased by 3.0% of potential GDP in calendar year 1937. Peppers only looks at the federal budget, and he finds that the cyclically adjusted federal government balance increased by 3.5% of potential GDP in calendar year 1937 and another 0.1% in 1938 for a total of 3.6% of potential GDP.

According to the April 2013 IMF World Economic Outlook (WEO) the U.S. general government structural (cyclically adjusted) balance will increase by 3.9% of potential GDP between calendar years 2010 and 2013. And the March 2013 CBO estimates of the cyclically adjusted federal budget balance show it will rise by 4.6% of potential GDP between fiscal years 2009 and 2013.

So apparently we have repeated the fiscal mistakes of 1937 with approximately a 30% bonus and yet the economy has not plunged into a renewed depression.

We know what Scott Sumner would say. Furthermore he would be right. It’s called “monetary offset.”

Still looking in vain for that darned liquidity trap Krugman keeps talking about!

Very good sentences

This raises an interesting, tangentially related question. Liberals fulminate constantly against outrageous conservative obstruction, yet often seem nevertheless surprised by its effectiveness. Why is that? My guess is that liberals are sometimes deceived by assumptions about the scope of liberalising moral progress. Modern history is a series of conservative disappointments, and the trend of social change does have a generally liberal cast. The surprisingly rapid acceptance of legal gay marriage is a good example. Liberals are therefore accustomed to a giddy sense of riding at the vanguard of history, routed reactionaries choking in their dust. But all of us, whatever our colours, overestimate the moral and intellectual coherence of our political convictions. We’re inclined to see meaningful internal connections between our opinions—between our views on abortion and regulatory policy, say—when often there’s no connection deeper than the contingent expediencies of coalition politics. For liberals, this sometimes plays out as a tendency to see resistance to all liberal policy as an inevitably losing battle against the inexorable tide of history. This occasionally leads, in turn, to a slightly naive sense of surprise when a hard-won political victory isn’t consolidated by a decisive, validating shift in public opinion, but instead begins to be ratcheted back.

That is from Will Wilkinson.

What did I learn from (another) re-read of Adam Smith?

Here is my MRU video on precisely that topic.

By the way, Brandon Dupont has done for us this excellent video on John Law.

The most provocative, fascinating, and bizarre piece I read today

The author is Ron Unz, and the topic is what the media chooses to cover or not. His thoughts run in directions very different than mine (I favor invisible hand mechanisms to a much greater degree, for one thing), but here is the essay.

It is entitled “Our American Pravda.” It is difficult to summarize. Maybe some parts of this essay are totally, completely wrong, so I urge you to read it with caution. But still I thought it was worth passing along; if nothing else you can read it as a study in how a situation can look “very guilty” even if perhaps it is not.

One excerpt is this:

These three stories—the anthrax evidence, the McCain/POW revelations, and the Sibel Edmonds charges—are the sort of major exposés that would surely be dominating the headlines of any country with a properly-functioning media. But almost no American has ever heard of them. Before the Internet broke the chokehold of our centralized flow of information, I would have remained just as ignorant myself, despite all the major newspapers and magazines I regularly read.

Am I absolutely sure that any or all of these stories are true? Certainly not, though I think they probably are, given their overwhelming weight of supporting evidence. But absent any willingness of our government or major media to properly investigate them, I cannot say more.

However, this material does conclusively establish something else, which has even greater significance. These dramatic, well-documented accounts have been ignored by our national media, rather than widely publicized. Whether this silence has been deliberate or is merely due to incompetence remains unclear, but the silence itself is proven fact.

The original pointer came from @GarethIdeas, who describes the piece as “totally fascinating.”

Why is there no Milton Friedman today?

You will find this question discussed in a symposium at Econ Journal Watch, co-sponsored by the Mercatus Center. Contributors include Richard Epstein, David R. Henderson, Richard Posner, Daniel Houser, James K. Galbraith, Sam Peltzman, and Robert Solow, among other notables. My own contribution you will find here, I start with these points:

If I approach this question from a more general angle of cultural history, I find the diminution of superstars in particular areas not very surprising. As early as the 18th century, David Hume (1742, 135-137) and other writers in the Scottish tradition suggested that, in a given field, the presence of superstars eventually would diminish (Cowen 1998, 75-76). New creators would do tweaks at the margin, but once the fundamental contributions have been made superstars decline in their relative luster.

In the world of popular music I find that no creators in the last twenty-five years have attained the iconic status of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, or Michael Jackson. At the same time, it is quite plausible to believe there are as many or more good songs on the radio today as back then. American artists seem to have peaked in enduring iconic value with Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns and Roy Lichtenstein, mostly dating from the 1960s. In technical economics, I see a peak with Paul Samuelson and Kenneth Arrow and some of the core developments in game theory. Since then there are fewer iconic figures being generated in this area of research, even though there are plenty of accomplished papers being published.

The claim is not that progress stops, but rather its most visible and most iconic manifestations in particular individuals seem to have peak periods followed by declines in any such manifestation.

David Brooks on the words we use

Daniel Klein of George Mason University has conducted one of the broadest studies with the Google search engine [TC: the paper is here]…On the subject of individualization, he found that the word “preferences” was barely used until about 1930, but usage has surged since. On the general subject of demoralization, he finds a long decline of usage in terms like “faith,” “wisdom,” “ought,” “evil” and “prudence,” and a sharp rise in what you might call social science terms like “subjectivity,” “normative,” “psychology” and “information.”

Klein adds the third element to our story, which he calls “governmentalization.” Words having to do with experts have shown a steady rise. So have phrases like “run the country,” “economic justice,” “nationalism,” “priorities,” “right-wing” and “left-wing.” The implication is that politics and government have become more prevalent.

So the story I’d like to tell is this: Over the past half-century, society has become more individualistic. As it has become more individualistic, it has also become less morally aware, because social and moral fabrics are inextricably linked. The atomization and demoralization of society have led to certain forms of social breakdown, which government has tried to address, sometimes successfully and often impotently.

This story, if true, should cause discomfort on right and left. Conservatives sometimes argue that if we could just reduce government to the size it was back in, say, the 1950s, then America would be vibrant and free again. But the underlying sociology and moral culture is just not there anymore. Government could be smaller when the social fabric was more tightly knit, but small government will have different and more cataclysmic effects today when it is not.

Liberals sometimes argue that our main problems come from the top: a self-dealing elite, the oligarchic bankers. But the evidence suggests that individualism and demoralization are pervasive up and down society, and may be even more pervasive at the bottom. Liberals also sometimes talk as if our problems are fundamentally economic, and can be addressed politically, through redistribution. But maybe the root of the problem is also cultural. The social and moral trends swamp the proposed redistributive remedies.

Here is more, interesting throughout.

The Adam Smith segment of the Great Economists course is underway

You will find it here, at MRUniversity.com. We have recorded videos covering, annotating, and explaining every single chapter of Smith’s masterwork Wealth of Nations, along with some coverage of surrounding historical material. Having to explain a book “along the way” is a very interesting way to read, and I was surprised how much Wealth of Nations rose in my eyes as a result of this project. I would like to do Keynes and Hayek and perhaps Marx in this manner as well.

On the proper interpretation of “The Great Stagnation”

Will Hutton writes:

At least Summers sees some underlying economic dynamism. For techno-pessimists such as economist Professor Tyler Cowen the future is even darker. It is not only that automation and robotisation are coming, but that there are no new worthwhile transformational technologies for them to automate. All the obvious human needs – to move, to have power, to communicate – have been solved through cars, planes, mobile phones and computers. According to Cowen, we have come to the end of the great “general purpose technologies” (technologies that transform an entire economy, such as the steam engine, electricity, the car and so on) that changed the world. There are no new transformative technologies to carry us forward, while the old activities are being robotised and automated. This is the “Great Stagnation”.

Such views make for a convenient target, but that is not close to what I wrote in The Great Stagnation. For instance on p.83 you will find me proclaiming, after several pages of details, “For these reasons, I am optimistic about getting some future low-hanging fruit.” Those are not Straussian passages hidden like the extra Nirvana audio track at the end of Nevermind. The very subtitle of the book announces “How America…(Eventually) Will Feel Better Again.”

I also argue in the book that the internet is the next transformational technology, and that it is already here, though it needs some time to mature and pay off. I devoted an entire separate book to this theme, namely The Age of the Infovore, which suggests that for autistics and other infovores massive progress already has arrived.

It is also odd that Hutton mentions robots and automation. My next book considers those factors in great detail, but you won’t find either term or variants thereof in the index of The Great Stagnation. Nor do I have the dual worry that both everything will be automated and there is nothing left to automate, as stated by Hutton.

The lesson perhaps is that if a book has a pessimistic-sounding title, mentions of optimism will go unheeded, even if they are in the subtitle. Might that be an example of the fallacy of mood affiliation?

*Stories We Tell*

Whose entire body of work is worth reading?

I’d be curious to see Tyler’s “completist” list. In other words, authors whose entire body of work merits reading. If this does get a response, I’m most interested in seeing the list begin with literature.

I’ll repeat my earlier mention of Geza Vermes. And to make the exercise meaningful, let’s rule out people who wrote one or two excellent books and then stopped. Adam Smith is too easy a pick. I won’t start with literature, however, but here are some choices:

1. Fernand Braudel.

2. George Orwell. Plato. Nietzsche and Kierkegaard. Hume. William James.

3. Franz Kafka, he died young.

4. T.J. Clark, historian of art and European thought.

5. J.C. D. Clark, the British historian.

Let’s stop here and take stock. Many historians will make the list, because if they are good they will find it difficult to produce crap. Without research, they cannot put pen to paper, and with research a careful, thoughtful historian is likely to be interesting. With thought you could come up with a few hundred historians who were consistently interesting and never wrote a bad book. Then you have a few extreme geniuses, and J.S. Mill might make the list if not for System of Logic, which by the way Mill himself thought stood among his best works. Timon of Athens hurts Shakespeare but he also comes very close.

Do any producers of “ideas books” make this list? Other than those listed under #2 of course. And are there truly consistent (and excellent) authors of fiction, other than those with a small number of works? I’m not thinking of many. How about Virginia Woolf or John Milton or Jane Austen?

One also could make an “opposite” of this list, namely important authors whose works are mostly not worth reading, and you could start with Conan Doyle, H.G. Wells, and Aldous Huxley. The existence of Kindle makes it easier to discover who these people really are.

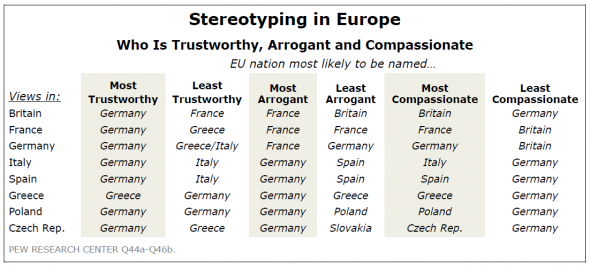

Stereotyping in Europe

Each column is interesting, for instance read down for “Most Compassionate.” It’s funny how many individuals do the same for themselves, I might add, in what has to be one of the simplest and most common of all intellectual mistakes.

Those results are from the new Pew report, summarized by David Keohane here. The French are growing increasingly disillusioned with the European project, and on key questions the French see the world as the Italians or Spanish do, not the Germans. And there is this: “The report also takes down a few German stereotypes. Apparently, Germans are among the least likely of those surveyed to see inflation as a very big problem and the most likely among the richer European nations to be willing to provide financial assistance to other European Union countries that have major financial problems.”

Thailand book bleg

From Chris Acree:

I’m planning a trip which will take me through Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. I recently began selecting a few books about each country to read to cover the history, culture, or other interesting aspects of the area. In particular, my favorite books in this vein are Country Driving and China Airborne, both about China.

However, in searching, I’ve found Cambodia has plenty of literature (Cambodia’s Curse by Pulitzer winner Joel Brinkley seems a good starting point), and Vietnam has at least a couple good books (I picked up Vietnam: Rising Dragon at your recommendation), whereas Thailand seems bereft of strong English-language histories or non-guide travel books. Amazon searches return almost exclusively books targeted towards sex tourists, and the Economist article here http://www.economist.com/node/16155881 is mostly over 10 years old. Kindle availability is also unavailable for most of their selections, which, while not a necessity for me, hints at books that aren’t aging well or being actively updated.

Has no reputable author written a great Thai travel book in the last 10 years? If not, why not? What books would you recommend on Thailand?

How about this biography of Bhumibol Adulyadej? Falcon of Siam is historical fiction of note. Thailand — Culture Smart! is good for browsing. You can read a variety of books on Jim Thompson, and speaking of Thompson this cookbook by David Thompson is a must. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives is one of the best movies ever made; watch these too, noting that Syndromes and a Century offers insight into the Thai health care system. I am not recommending use of such services, but perhaps the best of the books for sex tourists are interesting too? Siamese Soul is a good retro collection of Thai popular music from the 1960s through 1980s, hard on some ears but I like it.

Here is where Amazon sends you. Here is where Lonely Planet sends you. While you’re at it, why not read about Skyping with elephants in Thailand, in the service of science of course.

People, what else do you recommend?

C.S. Lewis on TV cooking shows

Well, in a time travel sort of way. Lewis once wrote this:

You can get a large audience together for a strip-tease act — that is, to watch a girl undress on the stage. Now suppose you come to a country where you could fill a theatre by simply bringing a covered plate on to the stage and then slowly lifting the cover so as to let every one see, just before the lights went out, that it contained a mutton chop or a bit of bacon, would you not think that in that country something had gone wrong with the appetite for food?

That quotation is from the new eBook by Steven Poole, You Aren’t What You Eat: Fed Up with Gastroculture. The book is cranky, often self-contradictory, and also reasonably entertaining.