Category: History

That was then, this is now

The fairly quick on his feet Captain Queeg nonetheless was relieved of his command:

Circa 1954.

Why don’t they compose music like Bach any more?

Well, they do, or at least they did once. I am thinking of a recent recording by Nikolaus Matthes, namely Markus Passion, which fills 3 compact discs and sounds remarkably like a Passion from Bach’s time. It could even be by Bach. The text is from the time of Bach. Yet Matthes was born in 1981.

To be clear, it does not rival Bach’s best work, but I have no problems comparing it to a median Bach cantata, which still is pretty good. It is also better than many of the works by Bach’s contemporaries, including the better-known ones.

And yet no one cares. Have you heard of this work before? How many times will you hear of it from now on?

Perhaps you doubt my judgment as to the quality of this work? Well, you might check out Fanfare, the world’s number one classical music review outlet. Fanfare gives the work six distinct reviews.

Colin Clarke for instance wrote: “But does it work? Absolutely. This is the most remarkable Baroque music of our time — by which I mean this does not feel like the 21st century looking back, instead, it feels as if it were written back in Bach’s time, with the exception of the odd detour forwards. Most of the time, it could be music written by Bach himself, and I can offer no higher praise to Matthes’s achievement.”

Or from David Cutler: “…Matthes has accomplished something marvelous. It has more than a hint of Bach, but is it Bach? The jury must be out on that, but is that not the idea?”

James A. Altena writes: “In sum, both the work itself and this performance are a complete triumph, and do full and worthy honor to Bach. I cannot think of higher praise than that.”

All the reviewers are very positive, as was a composer friend of mine who listened to the piece. The home page for the work offers further positive reviews. And no, I don’t like Prokofiev’s “Classical” Symphony.

You can buy it on German Amazon, and a few other places, streaming links here.

I feel I need to update some of my views on aesthetics, I am just not sure which ones. And who exactly is Matthes? Is this another Ossian thing, or rather the inverse?

Emile Zola’s The Ladies’ Paradise Reviewed by Furman

Jason Furman (eight years as a top economic adviser to President Obama) is an excellent economist who reads a lot of books. His Goodreads has 2300 books read, with some 1200 reviews in economics, fiction, history and science. I greatly enjoyed his latest review of Zola’s The Ladies Paradise which came about after he “asked a colleague in the English department if any fiction had positive depictions of business and capitalism (other than Ayn Rand).” Here is Furman’s review:

A 19th century novel that is a paean to the consumer welfare standard.

…The department store is really the leading character in this book, the protagonist of the Bildungsroman. It is like a living, breathing creature with needs, desires and most importantly constant growth. It becomes increasing complex, mature and alive as it develops. From a few departments to many, takes over more and more of the square block—eventually engulfing the one stubborn holdout. The novel also has amazing depictions of innovations, not just classical invention (e.g., an improved type of umbrella at one point) but also management of inventory, holding sales, selling some products at a loss, advertising, managing inventories, and more. I never thought an entire chapter of a novel (and they’re long chapters) devoted to inventory management could be so thrilling but that one was nothing compared to the description of the sale.

In the shadow of the Ladies Paradise are a number of small shops that are having an increasingly difficult time competing. The larger shop buys out some, builds on innovations by others, and aggressively competes on price with still others. Émile Zola does not sugarcoat the pain of all of this, depicting deaths and suicide attempts in the wake of the store. But he does not blame all the maladies on the Ladies Paradise itself and, consistent with the consumer welfare standard, he keeps the focus on the ways in which this profit ultimately benefits customers. Moreover, some of the small businesses do innovate in ways that help keep themselves in business: “longing to create competition for the colossus; [a small business owner] believed that victory would be certain if several specialized shops where customers could find a very varied choice of goods could be created in the neighbourhood.”

Interestingly there is a chapter that reads like an explanation of an economic model, Bertrand competition, in which two competitors keep lowering prices by smaller and smaller amounts until they are pricing as low as they possibly can (their marginal cost). What made this especially interesting to me was that The Ladies Paradise was published in 1883, the same year Joseph Louis François Bertrand published his model.

And it is not just consumers. The novel depicts how the productivity gains the Ladies Paradise makes as a result of its scale and its innovations are passed through to workers in the form of higher pay and improved benefits. For example, early on there is a brutal depiction of the process of laying off workers during the slow time of year. Later on, the store develops a system that is more like furloughs with insurance. And also, unlike the small shops in the area, it has opportunities for advancement within the store, moving up the ranks of managerial positions. Notably, all of this is not because of the benevolence of the owner (as it is in a few other 19th century novels) but because of competition from other stores so the need to attract and retain talent.

All of this makes employment in the colossus considerably better than the smaller, neighboring shops where people are poorly paid, lack opportunities for advancement and face harassment. Although it is still not all wonderful—for example, the department store frowns on women who are married and dismisses them when they have children.

Overall, the combination of low prices for consumers and high expenses—including pay and benefits to attract and retain employees—mean that the business has a very thin profit margin but applies that margin to a very large base: “Doubtless with their heavy trade expenses and their system of low prices the net profit was at most four per cent. But a profit of sixteen hundred thousand francs was still a pretty good sum; one could be content with four per cent when one operated on such a scale.”

The biggest wrinkle in the consumer welfare standard is some of the ambivalence Zola has about consumer preferences themselves….The idea that people—or women to be more specific—are buying things they do not “need” but “desire” is an issue it grapples with. And that desire can even rise to the level of a mad frenzy, like the sales it depicts or the shoplifters, some of them affluent but driven by an almost mad desire to acquire lace, silk, and more.

All of this is embedded in a larger economic and technological system that is operating in the background: large factories in Lyon that are producing at scale in a way that is symbiotic with the department store, rail transportation to bring the constant inflow of goods, a mail system that supports catalog purchases, and more.

…I’m still astounded about how breathtaking fiction can be made which understands and depicts the ways in which innovation and scale combine with competition to generate benefits for consumers and workers—while also not sugarcoating the many that lose from this process.

Thinking about the Roman Empire

The full title of the piece is “Identification and measurement of intensive economic growth in a Roman imperial province,” by Scott G. Ortman et.al. Here is the abstract:

A key question in economic history is the degree to which preindustrial economies could generate sustained increases in per capita productivity. Previous studies suggest that, in many preindustrial contexts, growth was primarily a consequence of agglomeration. Here, we examine evidence for three different socioeconomic rates that are available from the archaeological record for Roman Britain. We find that all three measures show increasing returns to scale with settlement population, with a common elasticity that is consistent with the expectation from settlement scaling theory. We also identify a pattern of increase in baseline rates, similar to that observed in contemporary societies, suggesting that this economy did generate modest levels of per capita productivity growth over a four-century period. Last, we suggest that the observed growth is attributable to changes in transportation costs and to institutions and technologies related to socioeconomic interchange. These findings reinforce the view that differences between ancient and contemporary economies are more a matter of degree than kind.

Thereby pondered! Via Alexander Le Roy.

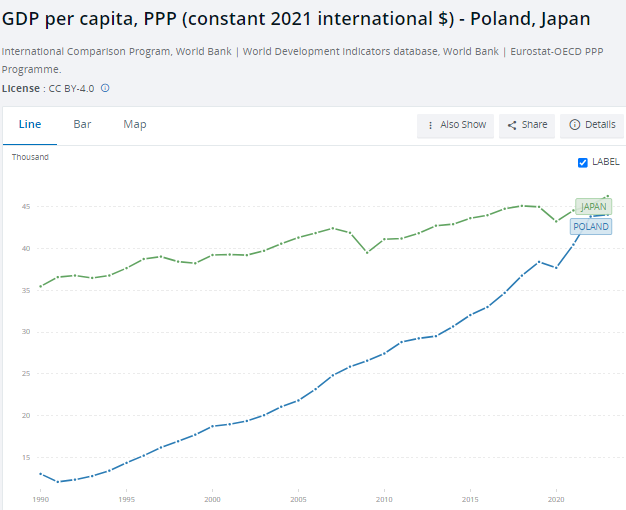

Poland’s PPP income is likely to exceed that of Japan by 2026.

Here is the link.

My excellent Conversation with Brian Winter

Here is the video, audio, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

It’s not just the churrasco that made him fall in love with Brazil. Brian Winter has been studying and writing about Latin America for over 20 years. He’s been tracking the struggles and triumphs of the region as it’s dealt with decades of coups, violence, and shifting economics. His work offers a nuanced perspective on Latin America’s persistent challenges and remarkable resilience.

Together Brian and Tyler discuss the politics and economics of nearly every country from the equator down. They cover the future of migration into Brazil, what it’s doing right in agriculture, the cultural shift in race politics, crime in Rio and São Paulo, the effectiveness and future consequences of Bukele’s police state in El Salvador, the economic growth of Colombia despite continued violence, the prevalence of startups and psychoanalysis in Argentina, Uruguay’s reduction in poverty levels, the beautiful ugliness of Sao Paulo, where Brian will explore next, and more.

And here is one excerpt;

COWEN: What’s the economic geography of Brazil going to look like? All the wealth near Mato Grosso and the north just very, very poor? Or the north empties out? How’s that going to work? There used to be some modest degree of balance.

WINTER: That’s true. Most of the population in Brazil and the economic center, for sure, was in the southeast. That means, really, São Paulo state, which is about a quarter of Brazil’s population but roughly a third of its GDP. Rio as well, and the state of Minas Gerais, which has a name that tells its history. That means “general mines” in Portuguese. That’s the area where a lot of the gold came out of in the 18th and 19th centuries. That’s gone now, so it’s not as much of an economic pull.

You’re right, Tyler, though, that a lot of the real boom right now, the action, is in places like Mato Grosso, which is in the region of Brazil called the Central West. That’s soy country. I’m from Texas, and Mato Grosso is virtually indistinguishable from Texas these days. It’s hot. It’s flat. The crop, like I said, is soy. There’s cattle ranching as well.

Even the music — Brazil, as others have noted, has gone from being the country of bossa nova and the samba in the 1970s to being the country of sertanejo today. Sertanejo is a Brazilian cousin of country music with accordions, but it’s sung by people — men mostly — in jeans, big belt buckles, and cowboy hats. They’re importing that — not only that economic model but that lifestyle as well.

COWEN: What is the great Brazilian music of today? MPB is dead, right? So, what should someone listen to?

Recommended, interesting throughout.

30th anniversary of the Brazilian real

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt, starting with the reality of Brazilian hyperinflation in the early 1990s:

Fortunately, economists and other reformers came to the rescue and designed an effective plan for currency stabilization. Brazil first created a virtual currency, called the URV, and switched contracts and prices to the new accounting unit. Next, a new currency, the real, was introduced as equal in value to the URV and roughly equal to the US dollar. That created the prospect of a new and more stable currency.

The crucial part of the reforms was a credible plan for fiscal stability. Brazil wasn’t experiencing hyperinflation for no reason — rather, the freshly printed money was needed to make good on promised government expenditures. So to make the numbers add up without hyperinflation, the Brazilian government carried out some budget cuts, privatized some assets, transferred some functions to state and local governments, and made some constitutional and legislative pledges in the direction of a balanced budget…

Yet the ending to this story is by no means entirely happy. For several years Brazil’s economy has been growing below 1%, though it has recently climbed above 2%. The country has bountiful natural resources, plenty of human talent, some excellent companies and universities, and no natural geopolitical enemies. Still, its economic growth has been mediocre. Brazil ought to be able to achieve annual growth of 4% to 6%.

The causes of this disappointing growth are varied and subject to dispute. Possible culprits include corruption, excess protectionism, an economy too dependent on natural resources, an unreliable education system and, perhaps, a loss of economic dynamism. In the golden years of the late 1960s and early ‘70s, Brazil had very high growth rates, hitting 14% in 1973, so extremely good performance is possible.

Worth a ponder.

Alice Evans on female labor force participation and appreciation of female talent

Abhay Aneja and colleagues reveal that daughters of civil servants who were more exposed to female co-workers during WWI were significantly more likely to work. For each standard deviation increase in exposure to female co-workers, the gender gap in labor force participation for children narrowed by over 4 percentage points. This represents a 9% decline in the average labor force participation gap. Importantly, these effects were

- Driven by increased labor force participation of daughters (sons are unaffected)

- Strongest for children who, at the time of exposure, were teenagers

- Present even for children who moved away from their parents’ original city

Here is the full post.

Large Firms in the South Korean Growth Miracle

We quantify the contribution of the largest firms to South Korea’s economic performance over the period 1972-2011. Using firm-level historical data, we document a novel fact: firm concentration rose substantially during the growth miracle period. To understand whether rising concentration contributed positively or negatively to South Korean real income, we build a quantitative heterogeneous firm small open economy model. Our framework accommodates a variety of potential causes and consequences of changing firm concentration: productivity, distortions, selection into exporting, scale economies, and oligopolistic and oligopsonistic market power in domestic goods and labor markets. The model is implemented directly on the firm-level data and inverted to recover the drivers of concentration. We find that most of the differential performance of the top firms is attributable to higher productivity growth rather than differential distortions. Exceptional performance of the top 3 firms within each sector relative to the average firms contributed 15% to the 2011 real GDP and 4% to the net present value of welfare over the period 1972-2011. Thus, the largest Korean firms were superstars rather than supervillains.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Jaedo Choi, Andrei A. Levchenko, Dimitrije Ruzic, and Younghun Shim.

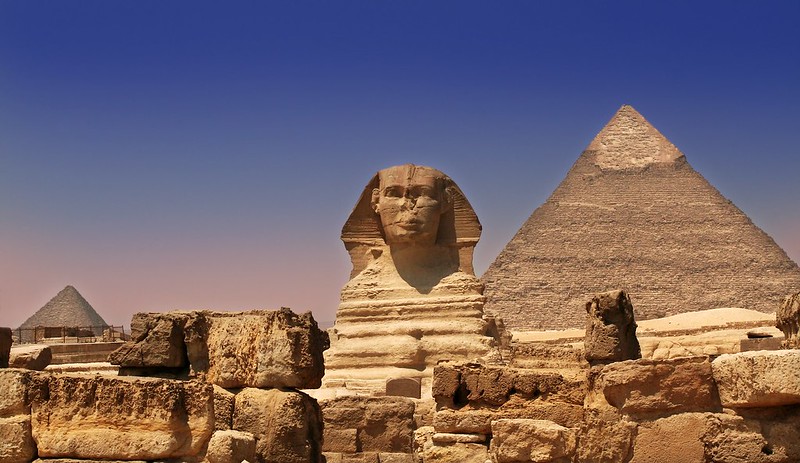

How Many Workers Did It Take to Build the Great Pyramid of Giza?

The Great Pyramid of Giza was built circa 2600 BC and was the world’s tallest structure for nearly 4000 years. It consists of an estimated 2.3 million blocks with a weight on the order of 6-7 million tons. How many people did it take to construct the Great Pyramid? Vaclav Smil in Numbers Don’t Lie gives an interesting method of calculation:

The Great Pyramid’s potential energy (what is required to lift the mass above ground level) is about 2.4 trillion joules. Calculating this is fairly easy: it is simply the product of the acceleration due to gravity, the pyramid’s mass, and its center of mass (a quarter of its height)…I am assuming a mean of 2.6 tons per cubic meter and hence a total mass of about 6.75 million tons.

People are able to convert about 20 percent of food energy into useful work, and for hard-working men that amounts to about 440 kilojoules a day. Lifting the stones would thus require about 5.5 million labor days (2.4 trillion/44000), or about 275,000 days a year during [a] 20 year period, and about 900 people could deliver that by working 10 hours a day for 300 days a year. A similar number might be needed to emplace the stones in the rising structure and then smooth the cladding blocks…And in order to cut 2.6 million cubic meters of stone in 20 years, the project would have required about 1,500 quarrymen working 300 days per year and producing 0.25 cubic meters of stone per capita…the grand total would then be some 3,300 workers. Even if we were to double that in order to account for designers, organizers and overseers etc. etc….the total would be still fewer than 7,000 workers.

…During the time of the pyramid’s construction, the total population of Egypt was 1.5-1.6 million people, and hence the deployed force of less than 10,000 would not have amounted to any extraordinary imposition on the country’s economy.

I was surprised at the low number and pleased at the unusual method of calculation. Archeological evidence from the nearby worker’s village suggests 4,000-5,000 on site workers, not including the quarrymen, transporters and designers and support staff. Thus, Smil’s calculation looks very good.

What other unusual calculations do you know?

*Emergency Money*

The author is Tom Wilkinson, and the subtitle is Notgeld in the Image Economy of the German Inflation, 1914-1923. Notgeld, or emergency money, typically was privately issued to make up for the deficiencies of government money during that period.

It is hard to think of a book that is more “for me.” The book covers history, monetary economics, private currency issuance, and the artistic renderings put on the private notes. You can see plenty of desperation in those visuals, and clearly the 19th century seems like a long time ago. I read this one right away upon arrival.

You can buy it here. Here is a good short piece on the art.

Deep roots, the persistent legacy of slavery on free labor markets

To engage with the large literature on the economic effects of slavery, we use antebellum census data to test for statistical differences at the 1860 free-slave border. We find evidence of lower population density, less intensive land use, and lower farm values on the slave side. Half of the border region was half underutilized. This does not support the view that abolition was a costly constraint for landowners. Indeed, the lower demand for similar, yet cheaper, land presents a different puzzle: why wouldn’t the yeomen farmers cross the border to fill up empty land in slave states, as was happening in the free states of the Old Northwest? On this point, we find evidence of higher wages on the slave side, indicating an aversion of free labor to working in a slave society. This evidence of systemically lower economic performance in slavery-legal areas suggests that the earlier literature on the profitability of plantations was misplaced, or at least incomplete.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Hoyt Bleakley and Paul Rhode.

The Gary Becker Papers

The Gary Becker Papers (117.42 linear feet, 223 boxes) are now open at the University of Chicago:

The collection documents much of Gary Becker’s intellectual history. One of his autobiographical essays, “A Personal Statement About My Intellectual Development” (see Box 120, Folder 10 and Box 189, Folder 1), traces his academic career from his youth to his origins as a student at Princeton University, to his graduate student years and professorship at the University of Chicago, and his extra collegial engagement on corporate advisory boards, political participation, and governmental councils. The essay could have been written based on some of the records collected here. The collection documents an intellectual trajectory primarily through intellectual productions, research files, and communications. His approach to the research and writing, his publishing history, his engagement with others in the field of economics and other individuals in public service and global politics are contained here. Though the collection primarily concerns his professional life, there is also mention of his relationship with Guity Nashat, his wife, as they traveled together to the many conferences and events in the United States and abroad, and other incidents of his life for a minor study or treatment of his biography.

The collection materials include Becker’s handwritten and printed copies of his scholarship, including notes (and bibliographic cards), papers (and drafts), diagrams and charts, data sheets, correspondence, periodical reprints, magazines, newspapers and clippings, grant documents, reports, referee files, course and instructional materials, photographs, VHS tapes, DVD’s, and related ephemera.

Hat tip: Peter Istzin.

*The Eastern Front: A History of the First World War*

That is the new book by Nick Lloyd, it will be making my best non-fiction of the year list. Reviews are very strong, and you can either pre-order and wait, or order it from the UK, or buy it in the excellent Hedengrens bookshop in Stockholm. Here is one short bit:

As always with the Russian army, squabbles between the generals quickly surfaced.

A bit later:

This lack of cooperation within the Russian high command would seriously undermine its operations throughout the war, preventing Russia from bringing all her strength to bear and forcing her commanders to spend precious time bickering amongst themselves.

About one-third of the way through the text of the book:

Tsar Nicholas II had come to a momentous decision: to take direct command of Russia’s armies.

How it started….how it’s going…

The Pentagon’s Anti-Vax Campaign

During the pandemic it was common for many Americans to discount or even disparage the Chinese vaccines. In fact, the Chinese vaccines such as Coronavac/Sinovac were made quickly and in large quantities and they were effective. The Chinese vaccines saved millions of lives. The vaccine portfolio model that the AHT team produced, as well as common sense, suggested the value of having a diversified portfolio. That’s why we recommended and I advocated for including a deactivated vaccine in the Operation Warp Speed mix or barring that for making an advance deal on vaccine capacity with China. At the time, I assumed that the disparaging of Chinese vaccines was simply an issue of national pride or bravado during a time of fear. But it turns out that in other countries, the Pentagon ran a disinformation campaign against the Chinese vaccines.

Reuters: At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. military launched a secret campaign to counter what it perceived as China’s growing influence in the Philippines, a nation hit especially hard by the deadly virus.

The clandestine operation has not been previously reported. It aimed to sow doubt about the safety and efficacy of vaccines and other life-saving aid that was being supplied by China, a Reuters investigation found. Through phony internet accounts meant to impersonate Filipinos, the military’s propaganda efforts morphed into an anti-vax campaign.

… Tailoring the propaganda campaign to local audiences across Central Asia and the Middle East, the Pentagon used a combination of fake social media accounts on multiple platforms to spread fear of China’s vaccines among Muslims at a time when the virus was killing tens of thousands of people each day. A key part of the strategy: amplify the disputed contention that, because vaccines sometimes contain pork gelatin, China’s shots could be considered forbidden under Islamic law.

…To implement the anti-vax campaign, the Defense Department overrode strong objections from top U.S. diplomats in Southeast Asia at the time, Reuters found. Sources involved in its planning and execution say the Pentagon, which ran the program through the military’s psychological operations center in Tampa, Florida, disregarded the collateral impact that such propaganda may have on innocent Filipinos.

“We weren’t looking at this from a public health perspective,” said a senior military officer involved in the program. “We were looking at how we could drag China through the mud.”

Frankly, this is sickening. The Pentagon’s anti-vax campaign has undermined U.S. credibility on the global stage and eroded trust in American institutions, and it will complicate future public health efforts. US intelligence agencies should be banned from interfering with or using public health as a front.

Moreover, there was a better model. It’s often forgotten but the elimination of smallpox from the planet, one of humanities greatest feats, was a global effort spearheaded by the United States and….the Soviet Union.

…even while engaged in a pitched battle for influence across the globe, the Soviet Union and the United States were able to harness their domestic and geopolitical self-interests and their mutual interest in using science and technology to advance human development and produce a remarkable public health achievement.

We could have taken a similar approach with China during the COVID pandemic.

More generally, we face global challenges, from pandemics to climate change to artificial intelligence. Addressing these challenges will require strategic international cooperation. This isn’t about idealism; it’s about escaping the prisoner’s dilemma. We can’t let small groups with narrow agendas and parochial visions undermine collaborations essential for our interests and security in an interconnected world.