Category: History

Orwell Against Progress

Orwell was deeply suspicious of technology and not simply because of the dangers of totalitarianism as expounded in 1984. In The Road to Wigan Pier, Orwell argues that technology saps vigor and will. He quotes disparagingly, World Without Faith, a pro-progress book written by John Beever, a proto Steven Pinker in this respect.

It is so damn silly to cry out about the civilizing effects of work in the fields and farmyards as against that done in a big locomotive works or an automobile factory. Work is a nuisance. We work because we have to and all work is done to provide us with leisure and the means of spending that leisure as enjoyably as possible.

Orwell’s response?

…an exhibition of machine-worship in its most completely vulgar, ignorant, and half-baked form….How often have we not heard it, that glutinously uplifting stuff about ’the machines, our new race of slaves, which will set humanity free’, etc., etc., etc. To these people, apparently, the only danger of the machine is its possible use for destructive purposes; as, for instance, aero-planes are used in war. Barring wars and unforeseen disasters, the future is envisaged as an ever more rapid march of mechanical progress; machines to save work, machines to save thought, machines to save pain, hygiene, efficiency, organization, more hygiene, more efficiency, more organization, more machines–until finally you land up in the by now familiar Wellsian Utopia, aptly caricatured by Huxley in Brave New World, the paradise of little fat men.

What’s Orwell’s problem with progress? He is a traditionalist. Orwell thinks that men need struggle, pain and opposition to be truly great.

…in a world from which physical danger had been banished–and obviously mechanical progress tends to eliminate danger–would physical courage be likely to survive? Could it survive? And why should physical strength survive in a world where there was never the need for physical labour? As for such qualities as loyalty, generosity, etc., in a world where nothing went wrong, they would be not only irrelevant but probably unimaginable. The truth is that many of the qualities we admire in human beings can only function in opposition to some kind of disaster, pain, or difficulty; but the tendency of mechanical progress is to eliminate disaster, pain, and difficulty.

..The tendency of mechanical progress is to make your environment safe and soft; and yet you are striving to keep yourself brave and hard.

I will give Orwell his due, he got this right:

Presumably, for instance, the inhabitants of Utopia would create artificial dangers in order to exercise their courage, and do dumb-bell exercises to harden muscles which they would never be obliged to use.

Orwell’s distaste for technology and love of the manly virtues of sacrifice and endurance to pain naturally push him towards zero-sum thinking. Wealth from machines is for softies but wealth from conquest, at least that makes you brave and hard! (See my earlier post, Orwell’s Falsified Prediction on Empire). Orwell didn’t favor conquest but it’s part of his pessimism that he sees the attraction.

Another of Orwell’s tragic dilemmas is that he doesn’t like progress but he does favor socialism and thus finds it unfortunate that socialism is perceived as being favorable to progress:

…the unfortunate thing is that Socialism, as usually presented, is bound up with the idea of mechanical progress…The kind of person who most readily accepts Socialism is also the kind of person who views mechanical progress, as such, with enthusiasm.

Orwell admired the tough and masculine miners he spent time with in the first part of Wigan Pier. In the second part he mostly decries the namby-pamby feminized socialists with their hippy-bourgeoise values, love of progress, and vegetarianism. I find it very amusing how much Orwell hated a lot of socialists for cultural reasons.

Socialism is too often coupled with a fat-bellied, godless conception of ’progress’ which revolts anyone with a feeling for tradition or the rudiments of

an aesthetic sense.…One sometimes gets the impression that the mere words ‘Socialism’ and ‘Communism’ draw towards them with magnetic force every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, ‘Nature Cure’ quack, pacifist, and feminist in England.

…If only the sandals and the pistachio coloured shirts could be put in a pile and burnt, and every vegetarian, teetotaller, and creeping Jesus sent home to Welwyn Garden City to do his yoga exercises quietly!

What Orwell wanted was to strip socialism from liberalism and to pair it instead with conservatism and traditionalism. (I am speaking here of the Orwell of The Road to Wigan Pier).

It’s still easy today to identify the sandal wearing, socialist hippies at the yoga studio but socialism no longer brings to mind visions of progress. Today, fans of progress are more likely to be capitalists than socialists. Indeed, socialism is more often allied with critiques of progress–progress destroys the environment, ruins indigenous ways of life and so forth. A traditionalist socialism along Orwell’s lines would add to this critique that progress destroys jobs, feminizes men, and saps vitality and courage. Thus, Orwell’s goal of pairing socialism with conservatism seems logically closer at hand than in his own time.

Orwell’s Falsified Prediction on Empire

In The Road to Wigan Pier, George Orwell argued:

…the high standard of life we enjoy in England depends upon our keeping a tight hold on the Empire, particularly the tropical portions of it such as India and Africa. Under the capitalist system, in order that England may live in comparative comfort, a hundred million Indians must live on the verge of starvation–an evil state of affairs, but you acquiesce in it every time you step into a taxi or eat a plate of strawberries and cream. The alternative is to throw the Empire overboard and reduce England to a cold and unimportant little island where we should all have to work very hard and live mainly on herrings and potatoes.

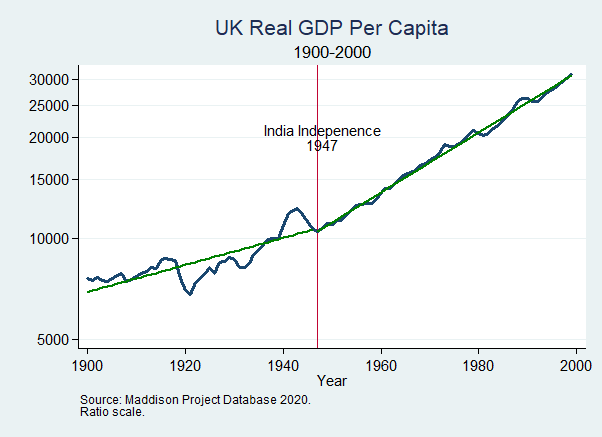

Wigan Pier was published in 1937 and a scant ten years later, India gained its independence. Thus, we have a clear prediction. Was England reduced to living mainly on herrings and potatoes after Indian Independence? No. In fact, not only did the UK continue to get rich after the end of empire, the growth rate of GDP increased.

Orwell’s failed prediction stemmed from two reasons. First, he was imbued with zero-sum thinking. It should have been obvious that India was not necessary to the high standard of living enjoyed in England because most of that high standard of living came from increases in the productivity of labor brought about by capitalism and the industrial revolution and most of that was independent of empire (Most. Maybe all. Maybe more than all. Maybe not all. One can debate the finer details on financing but of that debate I have little interest.) The second, related reason was that Orwell had a deep suspicion and distaste for technology, a theme I will take up in a later post.

Orwell, who was born in India and learned something about despotism as a police officer in Burma, opposed empire. Thus, his argument that we had to be poor to be just was a tragic dilemma, one of many that made him pessimistic about the future of humanity.

*The Corporation and the Twentieth Century*

The author is Richard N. Langlois, and the subtitle is The History of American Business Enterprise. 551 pp. of text. I’ve taught Ph.D Industrial Organization for a good while now, and have always wanted a text that provides an overview and introduction to U.S. business history, with sophistication and good economics, and without being out of date. This is that book, so I am happy indeed.

How effective was the IAEA?

Here is the Open AI call for international regulation, most of all along the lines of the International Atomic Energy Agency. I am not in general opposed to this approach, but I think it requires very strong bilateral supplements, from the United States of course. Which in turn requires U.S. supremacy in the area, as was the case with nuclear weapons. From a 564 pp. official work on the topic:

For nearly forty years after its birth in 1957 the IAEA remained essentially irrelevant to the nuclear arms race. (p.22)

There is also this:

However, in the late 1950s and early 1960s it was not the failure of the IAEA’s functions as a ‘pool’ or ‘bank’ or supplier of nuclear material that inflicted the most serious blow on the organization, on its safeguards operation and eventually on Cole himself. For a variety of reasons, the Agency’s chief patron, the USA, chose to arrange nuclear supplies bilaterally rather than through the IAEA. One reason was that the IAEA had been unable to develop an effective safeguards system. Another was that in a bilateral arrangement it was the US Administration, under the watchful eyes of Congress, that chose the bilateral partner rather than leaving the choice to an international organization that would have to respond to the needs of any Member State whatever its political system, persuasion or alliance. But the most serious setback came in 1958 when, for overriding political reasons, the USA chose the bilateral route in accepting the safeguards of EURATOM as equivalent to — in other words as an acceptable substitute for — those of the IAEA.

It is frequently suggested that the IAEA has been partially captured by the nuclear sector itself. I do not consider that bad news, but it is a sobering thought for those expecting too much from this approach. Do note that it took years to set up the agency, and furthermore when North Korea wanted to acquire nuclear weapons the country simply left the agency and broke its earlier agreement. Perhaps the greatest gain from this approach is that the non-crazy nations have a systematic multilateral framework to work within, should they decide to defer to the external, bilateral pressure from the United States?

On the other side, my fear is that the international agreement will lead to excess regulation at the domestic level.

There is also this:

The fact that Iraq’s nuclear weapon programme had been under way for several years, perhaps a decade, without being detected by the IAEA, led to sharp criticism of the Agency and posed the most serious threat to the credibility of its safeguards since they had first been applied some 30 years earlier.

All of these issues could use much more intelligent discussion.

Islam and human capital in historical Spain

We use a unique dataset on Muslim domination between 711-1492 and literacy in 1860 for about 7500 municipalities to study the long-run impact of Islam on human-capital in historical Spain. Reduced-form estimates show a large and robust negative relationship between length of Muslim rule and literacy. We argue that, contrary to local arrangements set up by Christians, Islamic institutions discouraged the rise of the merchant class, blocking local forms of self-government and thereby persistently hindering demand for education. Indeed, results show that a longer Muslim domination in Spain is negatively related to the share of merchants, whereas neither later episodes of trade nor differences in jurisdictions and different stages of the Reconquista affect our main results. Consistent with our interpretation, panel estimates show that cities under Muslim rule missed-out on the critical juncture to establish self-government institutions.

That is from a new paper by Francesco Cinnirella, Alieza Naghavi, and Giovanni Prarolo, via a loyal MR reader.

*The Fall of the Turkish Model*

The author is Cihan Tuğal, and the subtitle is How the Arab Uprisings Brought Down Islamic Liberalism, though the book is more concretely a comparison across Egypt and Tunisia as well, with frequent remarks on Iran. Here is one excerpt:

This led to what Kevan Harris has called the ‘subcontractor state’: an economy which is neither centralized under a governmental authority not privatized and liberalized. The subcontractor state has decentralized its social and economic roles without liberalizing the economy or even straightforwardly privatizing the state-owned enterprises. As a result, the peculiar third sector of the Iranian economy has expanded in rather complicated and unpredictable ways. Rather than leading to liberalization privatization under revolutionary corporatism intensified and twisted the significance of organization such as the bonyads…Privatization under the populist-conservative Ahmedinejad exploited the ambiguities of the tripartite division of the economy…’Privatization’ entailed the sale of public assets not to private companies but to nongovernmental public enterprises (such as pension funds, the bonyads and military contractors).

This book is one useful background source for the current electoral process in Turkey.

*Russia and China*

Authored by Philip Snow, the subtitle is Four Centuries of Conflict and Concord. This book is excellent and definitive and serves up plenty of economic history, here is one bit from the opening section:

The trade nonetheless went ahead with surprising placidity. Now and again there ere small incidents in the form of cattle-rustling or border raids. In 1742 some Russians were reported to have crossed the frontier in search of fuel, and in 1744 two drunken Russians killed two Chinese traders in a squabble over vodka.

I am looking forward to reading the rest, you can buy it here.

Substitutes Are Everywhere: The Great German Gas Debate in Retrospect

In March of 2022 a group of top economists released a paper analyzing the economic effects on Germany of a stop in energy imports from Russia (Bachmann et al. 2022). Using a large multi-sector mathematical model the authors concluded that if prices were allowed to adjust, even a substantial shock would have relatively low costs. In contrast, the German chancellor warned that if the Russians stopped selling oil to Germany “entire branches of industry would have to shut down” and when asked about the economic models he argued that:

[the economists] get it wrong! And it’s honestly irresponsible to calculate around with some mathematical models that then don’t really work. I don’t know absolutely anyone in business who doesn’t know for sure that these would be the consequences.

The Chancellor was not alone in predicting big economic losses; some studies estimated reductions in output of 6-12% and millions of unemployed workers. The key distinction between the economists and the others was in their understanding of elasticities of substitution. When the Chancellor and the average person think about a 40% reduction in natural gas supplies, they implicitly assume that each natural gas-dependent industry must cut its usage by 40%. They then consider the resulting decline in output and the cascading effects on downstream industries. It’s easy to get very worried using this framework.

When the economists replied that there were opportunities for substitution they were typically met with disbelief and misunderstanding. The disbelief stemmed from a lack of appreciation of the many opportunities for substitution that permeate an economy. In our textbook, Modern Principles, Tyler and I explain how the OPEC oil shock in the 1970s led to an increase in brick driveways (replacing asphalt) and the expansion of sugar cane plantations in Brazil (for ethanol production). Amazingly, the oil shock also prompted flower growers to move production overseas, as the reduction in heating oil costs from growing in sunnier climates outweighed the increase in transportation fuel expenses. While these examples highlight long-term changes, short-term substitutions are also possible, though their precise details are usually hidden from central planners and economists.

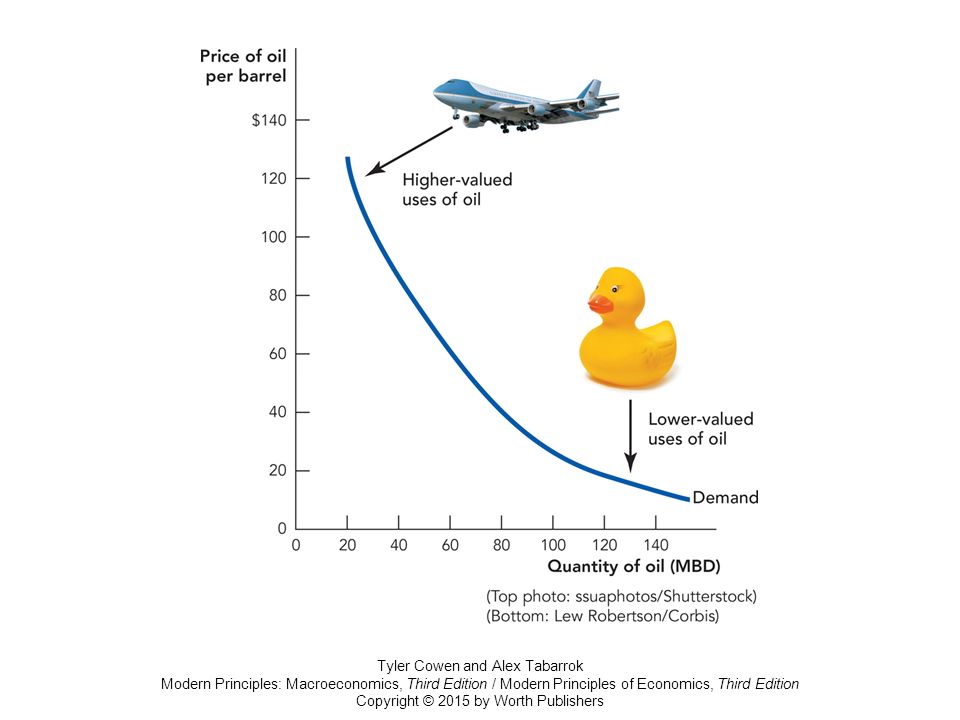

The misunderstanding came from thinking that we need every user of fuel to find substitutes. Not at all! In reality, as fuel prices rise, those with the lowest substitution costs will switch first, freeing up fuel for users who have more difficulty finding alternatives. Just one industry with favorable substitution possibilities, combined with a few moderately adaptable industries, can produce a significant overall effect. Moreover, there are nearly always some industries with viable substitution options. To see why reverse the usual story and ask, if fuel prices fell by 50% could your industry use more fuel? And if fuel prices fell by 50% are their industries that could switch into the now cheaper fuel?

The misunderstanding came from thinking that we need every user of fuel to find substitutes. Not at all! In reality, as fuel prices rise, those with the lowest substitution costs will switch first, freeing up fuel for users who have more difficulty finding alternatives. Just one industry with favorable substitution possibilities, combined with a few moderately adaptable industries, can produce a significant overall effect. Moreover, there are nearly always some industries with viable substitution options. To see why reverse the usual story and ask, if fuel prices fell by 50% could your industry use more fuel? And if fuel prices fell by 50% are their industries that could switch into the now cheaper fuel?

People often find it easier to imagine new uses rather than ways to reduce existing consumption. However, it is typically the new uses that are scaled back first. Tyler and I illustrate this with our jet and rubber ducky graph. Although jet aircraft won’t shift away from oil even at high prices, rubber (actually plastic) duckies, which are made from oil, can find substitutes–wood, for example–when oil prices rise. And if plastic ducky manufacturers cannot find substitutes, they go out of business, freeing up more oil for other uses. In this way, the market identifies the least valuable goods to cease production, another kind of substitution.

Substitution is a more nuanced concept than many people imagine. Here’s another example. Imagine that an economy has an energy-intensive goods producing sector and that there are few substitutes for the fuel used in this sector. Disaster? Not at all. We don’t need a fuel substitute, if we can substitute imports of the energy-intensive goods for domestically produced versions. Storage is also a substitute and notice that the more you substitute away from a fuel in final uses the greater the effective storage. If you use 1 gallon a day a 10 gallon tank lasts 10 days. If you use a quarter gallon a day it lasts 40 days. Everything is connected.

All of these myriad changes happen under the guidance of the invisible hand, i.e. the price system. Remember, a price is a signal wrapped up in an incentive. Thus Bachmann et al. wisely recommended letting energy prices rise to convey the signal and not insuring energy users so the incentive effects were fully felt on the margin.

So what happened? Gas from Russia was indeed cut very substantially but the German economy did not collapse and instead proved as robust as predicted, perhaps even more so. (The Chancellor’s predictions were off the mark but, to be fair, the government also did do a good job in sourcing new supplies and building reserves.) Moll, Schularick, and Zachmann have revisited the analysis and conclude:

The economic outcomes confirm the core theoretical argument that macro elasticities are larger than micro elasticities and that “cascading effects” along the supply chain would be muted as opposed to destroying the economy’s entire industrial sector. As foreseen, producers partly switched to other fuels or fuel suppliers, imported products with high energy content, while households adjusted their consumption patterns….Market economies have a tremendous ability to adapt that was widely underestimated. In addition, the German economics ministry (BMWK) was very successful in quickly sourcing gas supplies from third countries and building LNG capacity. Finally, it probably helped that German policymakers refrained from imposing a price cap on natural gas (like in many other European countries) and instead opted for lumpsum transfers based on households’ and firms’ historical gas consumption.

Hat tip: Alex Wollman.

*The Middle Kingdoms: A New History of Central Europe*

An excellent book by Martyn Rady, here is the passage most relevant to the history of economic thought:

A Norwegian economist and his wife have published a line of bestsellers in the field of economics written before 1750. Top is Aristotle’s Economics. Composed in the fourth century BCE, it is still available in paperback. Martin Luther’s denunciation of usury (1524) is number three. But there, in the top ten, is an unfamiliar name — Veit Ludwig von Seckendorff (1626-1692), who was a government official in the duchy of Saxe-Gotha in Thuringia. Seckendorff’s German Princely State (Teutscher Fürsten-Staat, 1656) is a thousand-page blockbuster that went through thirteen editions and was in continuous print for a century. Although only ever published in German, it was influential throughout Central Europe, shaping policy from the Banat to the Baltic.

I enjoyed this sentence:

Besides his distinctive false nose (the result of a duelling accident), Tycho Brahe kept an elk in his lodgings as a drinking companion.

And yes the book does have an insightful discussion of Laibach, the Slovenian hard-to-describe musical band. You can buy it here.

New blog on science and economic growth

By economist Jack Leach, here is the blog. Here is a post on the Greek origins of modern science.

Lessons from the COVID War

In preparation for a National Covid Commission a group of scholars directed by Philip Zelikow (director of the 9/11 Commission) began interviewing people and organizing task forces (I was an interviewee). The Covid Commission didn’t happen, a fact that illustrates part of the problem:

The policy agenda of both major American political parties appear mostly undisturbed by this pandemic. There is no momentum to fix the system….The Covid war revealed a collective national incompetence in governance….One common denominator stands out to us that spans the political spectrum. Leaders have drifted into treating this pandemic as if it were an unavoidable national catastrophe.

The results of this early investigation, however, are summarized in Lessons from the COVID WAR. Overall, a good book, not as pointed or data driven as I might have liked (see my talk for a more pointed overview), but I am in large agreement with the conclusions and it does contain some clarifying tidbits such as this one on the Obama playbook.

Innumerable speeches, books, and articles have stated that the Obama administration gave the incoming Trump administration a “playbook” on how to confront a pandemic and that this playbook was ignored. The Obama administration did indeed prepare and leave behind the “Playbook for Early Response to High-Consequence Emerging Infectious Disease Threats and Biological Incidents.”

But this playbook did not actually diagram any plays. There was no “how.” It did not explain what to do…when it came to the job of how to contain a pandemic that was headed for the United States in January 2020, the playbook was a blank page.

I also appreciated that Lessons has some some unheralded success stories from the state and local level. You may recall Tyler and I blogging repeatedly in 2020 about the advantages of pooled tests. Eventually pooled testing was approved but I haven’t seen data on how widely pooling was adopted or the effective increase in testing capacity that was produced. Lessons, however, offers an anecdote:

In San Antonio, a local charitable foundation paired with a blood bank to create a central Covid PCR testing lab (antigen tests were not yet readily available) that could combine samples (pooling) for efficiency and cost reduction, but also determine which individual in a pool was positive. Importantly, results were available within about twelve hours. That meant results were available before the start of school the new day.

The program helped San Antonio get kids back into the schools.

More generally, it’s striking that US schools were closed for far longer than French, German or Italian schools. See data at right on the number of weeks that “schools were closed, or party closed, to in-person instruction because of the pandemic (from Feb. 2020-March 2022)”. (South Korea, it should be noted, had some of the most advanced online education systems in the world.)

One general point made in Lessons that I wholeheartedly agree with this is that the school closures and many of the other controversial aspects of the pandemic response such as the lockdowns and mask mandates “were really symptoms of the deep problem. Without a more surgical toolkit, only blunt instruments were left.” With better testing, biomedical surveillance of the virus and honest communication we could have done better with much less intrusive and costly policies.

Addendum: See my previous reviews of Gottlieb’s Uncontrolled Spread, Michael Lewis’s The Premonition, Slavitt’s Preventable and Abutaleb and Paletta’s Nightmare Scenario.

Addendum 2: A typo in Lessons had France closing schools for 2 weeks instead of 12 weeks. Corrected.

Sebastian Edwards on Chilean social security reform

In his forthcoming book on the Chilean reforms, Edwards is clear that the social security reforms did not succeed. He gives the following reasons (a partial and incomplete summary):

1. “At 10 percent of wages, the rate of contribution was obviously too low. The average for the OECD countries was 19 percent.” Accumulated funds ended up being too low.

2. The system assumed a static labor market, where workers stayed in the formal sector for 30 to 50 years.

3. Workers were never quite sure if they really were going to get the funds, or if they just were paying another tax.

4. Workers’ representatives were not included on the relevant program boards, and so workers felt little stake in the system.

5. The number of retirement years rose dramatically, due in part to rising life expectancy. Yet the system made no adjustment for this, requiring a certain amount of savings to be stretched out to finance a growing number of years.

6. Management fees were very high, and this became a major issue when equity returns fell.

Here is my earlier post on the book — The Chile Project: The Story of the Chicago Boys and the Downfall of Neoliberalism, one of the must-reads of the year.

Hypergamy Revisited: Marriage in England, 1837-2021

There is a new paper by Greg Clark and Neil Cummins:

It is widely believed that women value social status in marital partners more than men, leading to female marital hypergamy, and more female intergenerational social mobility. A recent paper on Norway, for example, reports significant female hypergamy, even today, as measured by parental status of men and women in partnerships. Using evidence from more than 33 million marriages and 67 million births in England and Wales 1837-2022 we show that there was never within this era any period of significant hypergamous marriage by women. The average status of women’s fathers was always close to that of their husbands’ fathers. Consistent with this there was no differential tendency in England of men and women to marry by social status. The evidence is of strong symmetry in marital behaviors between men and women throughout. There is also ancillary evidence that physical attraction cannot have been a very significant factor in marriages in any period 1837-2021, based on the correlation observed in underlying social abilities.

Here is the link, oddly they are charging six pounds for access. Now there is an ungated version.

*The Chile Project*

An excellent book, the author is Sebastian Edwards, and the subtitle is The Story of the Chicago Boys and the Downfall of Neoliberalism. This is the only book on this topic where I feel I am finally getting to the bottom of what happened. Here are a few points:

1. The Chicago School ties to Chile go as far back as 1955, when Theodore Schultz, Earl Hamilton, Arnold Harberger, and Simon Rottenberg visited to strike up an agreement with Catholic University in Santiago.

2. The same year Chilean students started arriving at U. Chicago for graduate study.

3. Edwards himself, at the age of 19, worked on price controls under the Allende regime.

4. Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, the (left-wing) Austrian economist, was critical of the Allende regime for deviating from true socialism.

5. The Allende regime was a disaster, with for instance real wages falling by almost 40 percent (this one I knew).

6. Pinochet’s much-heralded private pension reform really did not work (I may do a whole post on this).

7. Milton Friedman’s famed visit really was quite modest, contrary to what you sometimes hear. Nonetheless he was so persuasive he really did convince Pinochet to proceed with the shock therapy version of reform. He had mixed feelings about this for the rest of his life, and did not like to talk about it: “But deep inside, Friedman was bothered by the Chilean episode.”

8. You may know that pegging the exchange rate was one of the major Chilean mistakes during the reform era. Friedman, although usually a strict advocate of floating exchange rates, did not take the opportunity to criticize that decision, and in fact made some remarks that suggested a possible willingness to tolerate a moving peg regime for the Chilean exchange rate.

9. Friedman underestimated how long Chilean unemployment would last, following shock therapy.

10. Arnold Harberger “…prided himself in not being doctrinaire and not being a Milton Friedman clone.”

11. Much more recently, Chile turned to the Left, in part because Chilean market-oriented economists retreated from public debates.

Strongly recommended, one of the must-reads of the year. You can buy it here.

The first recorded scientific grant system?

“Encouragements” from the French Académie des Sciences, 1831-1850.

The earliest recorded grant system was administered by the Paris-based Académie des Sciences following a large estate gift from Baron de Montyon. finding itself constrained in its ability to finance the research of promising but not-well-established savants, the academy seized on the flexiblity afford by the Montyon gift to transform traditional grands prix into “encouragements”: smaller amounts that could broaden the set of active researchers. Even though the process was highly informal (the names of the early recipients were not published in the academy’s Compte rendus), it apparently avoided suspected or actual cases of corruption…Throughout the 19th century, however, the academy struggled to convince wealthy donors to abandon their preference for indivisible, large monetary prizes in favor of these divisible encouragements.

That is from the Pierre Azoulay and Danielle Li essay “Scientific Grant Funding,” in the new and highly useful NBER volume Innovation and Public Policy, edited by Austan Goolsbee and Benjamin F. Jones. (But according to the book’s own theories, shouldn’t the book be cheaper than that?)