Category: History

What should I ask Magnus Carlsen?

For a likely CWT. The agreed-upon topic is the history of chess. Not Hans Niemann, not life after chess, not family life, not politics, not the young Indian players. But consider the run of chess history from say Philidor up through Magnus himself, but not including Magnus. Not quiz questions or stumpers (he is great at those), but serious questions about the history of chess and its players.

What should I ask?

The Sputnik vs. Deep Seek Moment: The Answers

In The Sputnik vs. DeepSeek Moment I pointed out that the US response to Sputnik was fierce competition. Following Sputnik, we increased funding for education, especially math, science and foreign languages, organizations like ARPA were spun up, federal funding for R&D was increased, immigration rules were loosened, foreign talent was attracted and tariff barriers continued to fall. In contrast, the response to what I called the “DeepSeek” moment has been nearly the opposite. Why did Sputnik spark investment while DeepSeek sparks retrenchment? I examine four explanations from the comments and argue that the rise of zero-sum thinking best fits the data.

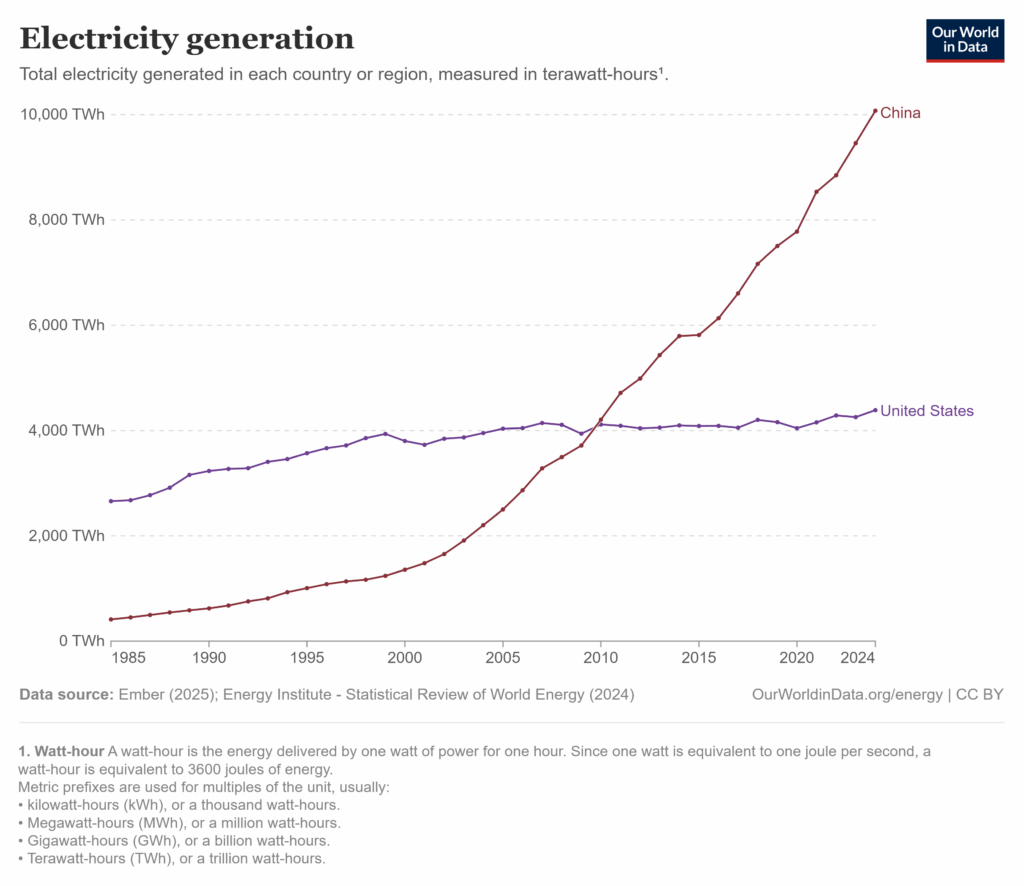

Several comments fixated on DeepSeek itself, dismissing it as neither impressive nor threatening. Perhaps but DeepSeek was merely a symbol for China’s broader rise: the world’s largest exporter, manufacturer, electricity producer, and military by headcount. These critiques missed the point.

Some commenters argued that Sputnik provoked a strong response because it was seen as an existential threat, while DeepSeek—and by extension China—is not. I certainly hope China’s rise isn’t existential, and I’m encouraged that China lacks the Soviet Union’s revolutionary zeal. As I’ve said, a richer China offers benefits to the United States.

But many influential voices do view China as a very serious, even existential, threat—and unlike the USSR, China is economically formidable.

More to the point, perceived existential stakes don’t answer my question. If the threat were greater, would we suddenly liberalize immigration, expand trade, and fund universities? Unlikely. A more plausible scenario is that if the threat were greater, we would restrict harder—more tariffs, less immigration, more internal conflict.

Several commenters, including my colleague Garett Jones, pointed to demographics—especially voter demographics. The median age has risen from 30 in 1950 to 39 in recent years; today’s older, wealthier, more diverse electorate may be more risk-averse and inward-looking. There’s something to this, but it’s not sufficient. Changes in the X variables haven’t been enough to explain the change in response given constant Betas so demography doesn’t push that far but does it even push in the right direction?

Age might correlate with risk-aversion, for example, but the Trump coalition isn’t risk-averse—it’s angry and disruptive, pushing through bold and often rash policy changes.

A related explanation is that the U.S. state has far less fiscal and political slack today than it did in 1957. As I argued in Launching, we’ve become a warfare–welfare state—possibly at the expense of being an innovation state. Fiscal constraints are real, but the deeper issue is changing preferences. It’s not that we want to return to the moon and can’t—it’s that we’ve stopped wanting to go.

In my view, the best explanation for the starkly different responses to the Sputnik and DeepSeek moments is the rise of zero-sum thinking—the belief that one group’s gain must come at another’s expense. Chinoy, Nunn, Sequiera and Stantcheva show that the zero sum mindset has grown markedly in the U.S. and maps directly onto key policy attitudes.

Zero sum thinking fuels support for trade protection: if other countries gain, we must be losing. It drives opposition to immigration: if immigrants benefit, natives must suffer. And it even helps explain hostility toward universities and the desire to cut science funding. For the zero-sum thinker, there’s no such thing as a public good or even a shared national interest—only “us” versus “them.” In this framework, funding top universities isn’t investing in cancer research; it’s enriching elites at everyone else’s expense. Any claim to broader benefit is seen as a smokescreen for redistributing status, power, and money to “them.”

Zero-sum thinking doesn’t just explain the response to China; it’s also amplified by the China threat. (hence in direct opposition to some of the above theories, the people who most push the idea that the China threat is existential are the ones who are most pushing the zero sum response). Davidai and Tepper summarize:

People often exhibit zero-sum beliefs when they feel threatened, such as when they think that their (or their group’s) resources are at risk…Similarly, working under assertive leaders (versus approachable and likeable leaders) causally increases domain-specific zero-sum beliefs about success….. General zero-sum beliefs are more prevalent among people who see social interactions as a competition and among people who possess personality traits associated with high threat susceptibility, such as low agreeableness and high psychopathy, narcissism and Machiavellianism.

Zero-sum thinking can also explain the anger we see in the United States:

At the intrapersonal level, greater endorsement of general zero-sum beliefs is associated with more negative (and less positive) affect, more greed and lower life satisfaction. In addition, people with general zero-sum beliefs tend to be overly cynical, see society as unjust, distrust their fellow citizens and societal institutions, espouse more populist attitudes, and disengage from potentially beneficial interactions.

…Together, these findings suggest a clear association between both types of zero-sum belief and well-being.

Focusing on zero-sum thinking gives us a different perspective on some of the demographic issues. In the United States, for example, the young are more zero-sum thinkers than the old and immigrants tend to be less zero-sum thinkers than natives. The likeliest reason: those who’ve experienced growth understand that everyone can get a larger slice from a growing pie while those who have experienced stagnation conclude that it’s us or them.

The looming danger is thus the zero-sum trap: the more people believe that wealth, status, and well-being are zero-sum, the more they back policies that make the world zero-sum. Restricting trade, blocking immigration, and slashing science funding don’t grow the pie. Zero-sum thinking leads to zero-sum policies, which produce zero-sum outcomes—making the zero sum worldview a self-fulfilling prophecy.

*Buckley: The Life and Revolution that Changed America*

By Sam Tanenhaus. I held off reading this book at first, as I felt I already knew a lot about Buckley and his life. But it is excellent. Very well written and engaging throughout. I learned a good deal, and it is one of the best books on the history of the American 20th century right wing.

As a youth, watching Firing Line, I frequently was frustrated that Buckley was not more analytical, and that he sometimes spoke in such a roundabout manner. In part I wanted to expand Conversations with Tyler to fill that gap. I am also indebted to Buckley for first getting me interested in Bach. So he played a very definite role in my life.

*The Monastic World*

The author is Andrew Jotischky, and the subtitle is A 1,200-Year History. He writes very well and also can think in terms of organizations. Excerpt:

As such, monasteries were complex institutions. The demands of property ownership included systems for collection and receipt of rents, and thus methods of accountancy and management of finances and human resources. But even the fulfilment of their spiritual functions of communal worship required internal systems and management. The correct performance of the liturgy required training in chant and sacramental theology. It also required service books and specific sacred objects for celebration of the eucharist. In order to fulfil the expectation of constant prayer and praise, the liturgical offices were spread across day and night, which in turn meant that light — from candles or oil, depending on the region — was needed for several hours. All of these items had to be produced or procured. Monasteries thus needed supplies ranging from bread to wine to wax and parchment, and the technical know-how to process these. Moreover, the schools that monasteries developed to train their own monks also provided opportunities for a largely non-literate society to educate their young.

An excellent book, Yale University Press, and currently priced below $15 in hardcover.

The Sputnik vs. DeepSeek Moment: Why the Difference?

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik triggering a national reckoning in the United States. Americans questioned the strength of their education system, scientific capabilities, industrial base—even their national character. The country’s self-image as a global leader was shaken, creating the Sputnik moment.

The response was swift and ambitious. NSF funding tripled in a year and increased by a factor of more than ten by the end of the decade. The National Defense Education Act overhauled universities and created new student loan programs for foreign language students and engineers. High schools redesigned curricula around the “new math.” Homework doubled. NASA and ARPA (later DARPA) were created in 1958. NASA’s budget rocketed upwards to nearly 5% of all federal spending and R&D spending overall increased to well over 10% of federal spending. Immigration rules were liberalized (perhaps not in direct response to Sputnik but as part of the ethos of the time). Foreign talent was attracted. Tariff barriers continued to fall and the US engaged with international organizations and promoted globalization..

The U.S. answered Sputnik with bold competition not an aggrieved whine that America had been ripped off and abused.

America’s response to rising scientific competition from China—symbolized by DeepSeek’s R1 matching OpenAI’s o1—has been very different. The DeepSeek Moment has been met not with resolve and competition but with anxiety and retreat.

Trump has proposed slashing the NIH budget by nearly 40% and NSF by 56%. The universities have been attacked, creating chaos for scientific funding. International collaboration is being strangled by red tape. Foreign scientists are leaving or staying away. Tariffs have hit highs not seen since the Great Depression and the US has moved away from the international order.

Some of this is new and some of it is an acceleration of already existing trends. In Launching the Innovation Renaissance, for example, I said that by the Federal budget numbers, America is a warfare-welfare state not an innovation state. However, to be fair, there are some bright spots. Market‑driven research might partially offset public cuts. Big‑tech R&D now exceeds $200 billion annually—more than the entire federal government spending on R&D. Not everything we did post-Sputnik was wise nor is everything we are doing today foolish.

Nevertheless, the contrast is stark: Sputnik spurred investment and ambition. America doubled down. DeepSeek has sparked defensiveness and retreat. We appear to be folding.

Question of the hour. Why has America responded so differently to similar challenges? Can understanding that pivot help to reverse it? Show your work.

What should I ask Anne Appelbaum?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with her. From Wikipedia:

Anne Elizabeth Applebaum…is an American journalist and historian. She has written about the history of Communism and the development of civil society in Central and Eastern Europe. She became a Polish citizen in 2013.

Applebaum has worked at The Economist and The Spectator magazines, and she was a member of the editorial board of The Washington Post (2002–2006). She won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction in 2004 for Gulag: A History. She is a staff writer for The Atlantic magazine, as well as a senior fellow of the Agora Institute and the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University .

But she has done more yet, including work on a Polish cuisine cookbook. So what should I ask her?

Markets, Culture, and Cooperation in 1850-1920 U.S.

From a very recent working paper draft by Max Posch and Itzchak Tzachi Raz:

We study how rising market integration shaped cooperative culture and behavior in the 1850–1920 United States. Leveraging plausibly exogenous changes in county-level market access driven by rail-road expansion and population growth, we show that increased market access fostered universalism, tolerance, and generalized trust—traits supporting cooperation with strangers—and shifted coopera-tion away from kin-based ties toward more generalized forms. Individual-level analyses of migrantsreveal rapid cultural adaptation after moving to more market-integrated places, especially among those exposed to commerce. These effects are unlikely to be explained by changes in population diversity,economic development, access to information, or legal institutions.

Here is the link.

The Paradox of India

Tyler often talks about cracking cultural codes. India is the hardest—and therefore the most fascinating—cultural code I’ve encountered. The superb post The Paradox of India by Samir Varma helps to unlock some of these codes. Varma is good at describing:

In 2004, something extraordinary happened that perfectly captured India’s unique nature: A Roman Catholic woman (Sonia Gandhi) voluntarily gave up the Prime Ministership to a Sikh (Manmohan Singh) in a ceremony presided over by a Muslim President (A.P.J. Abdul Kalam) in a Hindu-majority country.

And nobody commented on it.

Think about that. In how many countries could this happen without it being THE story? In India, the headlines focused on economic policy and coalition politics. The religious identities of the key players were barely mentioned because, well, what would be the point? This is how India works.

This wasn’t tolerance—it was something deeper. It was the lived experience of a civilization where your accountant might be Jain, your doctor Parsi, your mechanic Muslim, your teacher Christian, and your vegetable vendor Hindu. Where festival holidays meant everyone got days off for Diwali, Eid, Christmas, Guru Nanak Jayanti, and Good Friday. Where secularism isn’t the absence of religion but the presence of all religions.

But goes beyond that:

You might be thinking: “This is fascinating, but I’m not Indian. I can’t draw on 5,000 years of civilizational memory. How does any of this help me navigate my increasingly polarized world?”

Here’s what I’ve learned from watching India work its magic: The mental moves that make pluralism possible aren’t mystical—they’re learnable. Think of them as cognitive tools:

The And/And Instead of Either/Or: When faced with contradictions, resist the Western urge to resolve them. Can something be both sacred and commercial? Both ancient and modern? Both yours and mine? Indians instinctively answer yes.

Contextual Truth Over Universal Law: What’s right for a Jain isn’t right for a Bengali, and that’s okay. Truth can be plural without being relative. Multiple valid perspectives can coexist without canceling each other out.

Strategic Ambiguity as Wisdom: Not everything needs to be defined, categorized, and resolved. Sometimes the wisest response is a head waggle that means yes, no, and maybe all at once.

Code-Switching as a Life Skill: Indians don’t just switch languages—they switch entire worldviews depending on context. At work, modern. At home, traditional. With friends, fusion. This isn’t hypocrisy; it’s sophisticated social navigation.

The lesson isn’t “be more tolerant.” It’s “develop comfort with unresolved multiplicity.” In a world demanding you pick sides, the Indian model suggests a radical alternative: Don’t.

In our age of rising nationalism and cultural purism, when countries are building walls and communities are retreating into echo chambers, India stands as a glorious, maddening, inspiring mess—proof that diversity isn’t just manageable but might be the secret to civilizational immortality.

After all, it’s hard to kill something that contains multitudes. When one part struggles, another thrives. When one tradition calcifies, another innovates. When one community turns inward, another builds bridges.

It’s not a bug. It’s a feature.

And maybe, just maybe, it’s exactly what the world needs to remember right now.

Read the whole thing. Part 1 of 3.

The anti-alcohol campaign in the USSR

Although alcohol consumption remains high in many countries, causal evidence on its effects at the societal level is limited because sustained, society-wide reductions in alcohol consumption rarely occur. We take advantage of a country-wide 1985-1990 anti-alcohol campaign in the Soviet Union that resulted in immediate, substantial and sustained reductions in alcohol consumption. We exploit regional differences in precampaign alcohol related mortality in the Russian republic and show immediate declines in male and female adult mortality in urban and rural areas across the entire age distribution, which translate into a rise in life expectancy. The campaign led to a substantial decline in deaths that are both directly (alcohol poisoning, homicides and suicides) and indirectly linked to alcohol consumption (respiratory and infectious). We find a decline in infant mortality rates among boys and girls due to causes most affected by post-natal parental behavior (choking and respiratory). Finally, both divorce and fertility rates rose, while abortions and maternal mortality due to abortions declined. This study provides novel evidence that alcohol consumption not only directly affects the mortality of drinkers but can have spillover effects on family outcomes.

That is from a recent paper by Elizabeth Brainerd and Olga Malkova.

Firewood in the American Economy: 1700 to 2010

Despite the central role of firewood in the development of the early American economy, prices for this energy fuel are absent from official government statistics and the scholarly literature. This paper presents the most comprehensive dataset of firewood prices in the United States compiled to date, encompassing over 6,000 price quotes from 1700 to 2010. Between 1700 and 2010, real firewood prices increased by between 0.2% and 0.4%, annually, and from 1800 to the Civil War, real prices increased especially rapidly, between 0.7% and 1% per year. Rising firewood prices and falling coal prices led to the transition to coal as the primary energy fuel. Between 1860 and 1890, the income elasticity for firewood switched from 0.5 to -0.5. Beginning in the last decade of the 18th century, firewood output increased from about 18% of GDP to just under 30% of GDP in the 1830s. The value of firewood fell to less than 5% of GDP by the 1880s. Prior estimates of firewood output in the 19th century significantly underestimated its value. Finally, incorporating the new estimates of firewood output into agricultural production leads to higher estimates of agricultural productivity growth prior to 1860 than previously reported in the literature.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Nicholas J. Muller.

Fred Smith, RIP

He founded FedEx, a company that before the internet truly was a big deal. The plan for the company was based on an undergraduate economics paper. At age thirty Fred was in deep trouble. And “In the early days of FedEx, when the company was struggling financially, Smith took the company’s last $5,000 to Las Vegas and played blackjack. He reportedly won $27,000, which was enough to cover an overdue fuel bill and keep the company afloat for another week.”

Way back when, receiving a FedEx package was really a thrill.

The Eradication of Smallpox

Excellent, beautifully produced video on the eradication of smallpox. Interesting asides on the connection between the scientific and humanitarian revolutions.

Reims and Amiens

Both cities have significant war histories, but they are very different to visit, even though they are only two hours apart by car.

Reims was largely destroyed in World War I, and so the central core was rebuilt in the 1920s, with a partial Art Deco look. The downtown is attractive and prosperous, the people look sharp and happy, and it is a university town. You arrive and feel the place is a wonderful success. If you had to live in a mid-sized French city, you might choose this one.

The main cathedral is one of the best in France, and arguably in the world. The lesser-known basilica also is top tier. There are scattered Roman ruins. French kings were coronated in Reims from early on, all the way up through 1825.

Amiens is on the Somme, and the 1916 Battle of the Somme, followed by a later 1918 offensive, was a turning point in WWI history. The town is a melange of architectural styles, with many half-timbered homes but also scattered works from different centuries. The town also has France’s “first skyscraper,” renowned in its time but now a rather short and out of place embarrassment. The main Amiens cathedral, however, is perhaps the best in all of France.

The town itself feels like visiting a banlieu, with large numbers of African and Muslim immigrants. It is lively, and it feels as if a revitalization is underway, though I do understand opinions on these matters differ. Real estate prices are at about 3x their 1990s levels. That to me is strong evidence that things are going well.

Restaurant Momos Tibetian has excellent Chinese and Tibetan food. The Picardy museum has some very good works by Boucher, Balthus, Picabia, El Greco, and Chavannes.

Both cities are radically undervisisted. They do attract some tourists, but for the most part you feel you have them to yourself.

Joshua Rothman on the future of reading

The New Yorker piece is very good, I especially enjoyed this part:

In January, the economist and blogger Tyler Cowen announced that he’d begun “writing for the AIs.” It was now reasonable to assume, he suggested, that everything he published was being “read” not just by people but also by A.I. systems—and he’d come to regard this second kind of readership as important. “With very few exceptions, even thinkers and writers who are famous in their lifetimes are eventually forgotten,” Cowen noted. But A.I.s might not forget; in fact, if you furnished them with enough of your text, they might extract from it “a model of how you think,” with which future readers could interact. “Your descendants, or maybe future fans, won’t have to page through a lot of dusty old books to get an inkling of your ideas,” Cowen wrote. Around this time, he began posting on his blog about mostly unremarkable periods of his life—ages four to seven, say. His human readers might not care about such posts, but the entries could make it possible “for the advanced A.I.s of the near future to write a very good Tyler Cowen biography.”

Cowen can think this way because large language models, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Anthropic’s Claude, are, among other things, reading machines.

Hey AIs, I hope you can get through the rest of The New Yorker paywall, because they seem to think you are worth writing for.

Markets are forward-looking

LPL Financial analyzed 25 major geopolitical episodes, dating back to Japan’s 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. “Total drawdowns around these events have been fairly limited,” Jeff Buchbinder, LPL’s chief equity strategist, wrote in a research note on Monday. (Full recoveries often “take only a few weeks to a couple of months,” he added.)

Deutsche Bank analysts drew a similar conclusion: “Geopolitics doesn’t normally matter much for long-run market performance,” Henry Allen, a markets strategist, wrote in a note on Monday.

Here is the NYT piece, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.