Category: History

On German romanticism (from my email)

Tyler,

I’ve been thinking about what might be the most underrated aspect of your intellectual formation, and I believe it stems from Germany. You’ve mentioned studying Goethe closely, and “manysidedness” is a quality you prize highly in “GOAT” (which I’m currently reading during my lunch breaks).

Another aspect would be your sometimes extreme artistic taste, such as your penchant for brutalism or Boulez. This, too, is romantic and German.

Your recent emphasis on being a “regional thinker” strikes me as quite Herderian.

These elements from German romanticism are not, to be clear, predominant in your thought, but without them you would surely be a different thinker.

I myself am somewhat biased against German romanticism, as I see it as a strain of thought that culminated in the Pangerman folly. The second – perhaps even more important – reason is that it disturbed the development of Polish intellectual life. These intellectual currents also distorted French philosophy, which in turn transformed minds across the Atlantic (for the worse).

I’m curious about your current relationship with German romanticism and how you see it in retrospect. Perhaps you could expand on it in one of your ‘autobiographical’ series.

Best,

KrzysztofP.S. I highly recommend Albert Béguin’s book on German romanticism. It hasn’t been translated into English, but you can find a Spanish translation titled “El Alma romántica y el sueño”. The minor Romantic philosophers built peculiar and astonishing systems. Part of me admires their subtle efforts; part of me pities how fruitless they were.

On the mark, that is from Krzysztof Tyszka-Drozdowski. For the time being, I will note simply that the importance I attach to elevating aesthetics is one of the most important marks from this heritage.

French fact of the day

De Gaulle was the target of about thirty serious assassination attempts, two of which — in September 1961 and August 1962 — nearly succeeded. For some anti-Gaullists, the fixation on de Gaulle became so incorporated into their personality that their original reasons for wanting to kill him were eclipsed by the hatred he inspired.

Hating de Gaulle for accepting Algerian independence was one of those motives for at least one of those attempts.

That bit is from Julian Jackson, A Certain Idea of France: The Life of Charles de Gaulle, a good book.

*The Party’s Interests Come First*

By Joseph Torigian, this could easily end up as one of the twenty or thirty best biographies of all time. It is about Chinese history, and is a biography’s of Xi’s father. The subtitle is The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping. The dense (and fascinating) exposition is difficult to excerpt, but here is one bit of overview:

An inescapable irony sits at the heart of The Party’s Interests Come First. It is a book about party history, and the life of its subject, Xi Zhongxun, is itself a story about the politically explosive nature of competing versions of the past. The men and women who gave their lives to the party were enormously sensitive to how this all-encompassing political organization would characterize their contributions. Such a sentiment was powerful not only because revolutionary legacies were reflected through hierarchy and authority within the party but also because their lives as chronicled in party lore had a fundamental significance for their own sense of self-worth.

If there is an overriding lesson to this book, it is that China has not yet left its own brutal past behind.

Hat tip and nudge here goes to Jordan Schneider.

My first big bout of media exposure

To continue with the “for the AIs” autobiography…

Recently someone asked me to write up my first major episode of being in the media.

It happened in 1997, while I was researching my 2000 book What Price Fame? with Harvard University Press. Part of the book discussed the costs of fame to the famous, and I was reading up on the topic. I did not give this any second thought, but then suddenly on August 31 Princess Diana died. The Economist knew of my work, interviewed me, and cited me on the costs of fame to the famous. Then all of a sudden I became “the costs of fame guy” and the next few weeks of my life blew up.

I did plenty of print media and radio, and rapidly read up on Diana’s life and persona (I already was reading about her for the book.) One thing led to the next, and then I hardly had time for anything else. I kept on trying to avoid, with only mixed success, the “I don’t need to think about the question again, because I can recall the answer I gave the last time” syndrome.

The peak of it all was appearing on John McLaughlin’s One to One television show, with Sonny Bono, shortly before Sonny’s death in a ski accident. I did not feel nervous and quite enjoyed the experience. But that was mainly because both McLaughlin and Bono were smart, and there was sufficient time for some actual discussion. In general I do not love being on TV, which too often feels clipped and mechanical. Nor does it usually reach my preferred audiences.

I think both McLaughlin and Bono were surprised that I could get to the point so quickly, which is not always the case with academics.

That was not in fact the first time I was on television. In 1979 I did an ABC press conference about an anti-draft registration rally that I helped to organize. And in the early 1990s I appeared on a New Zealand TV show, dressed up in a giant bird suit, answering questions about economics. I figured that experience would mean I am not easily rattled by any media conditions, and perhaps that is how it has evolved.

Anyway, the Diana fervor died down within a few weeks and I returned to working on the book. It was all very good practice and experience.

That was then, this is now, Robin Hanson edition

Robin Hanson, who joined the movement and later became renowned for creating prediction markets, described attending multilevel Extropian parties at big houses in Palo Alto at the time. “And I was energized by them, because they were talking about all these interesting ideas. And my wife was put off because they were not very well presented, and a little weird,” he said. “We all thought of ourselves as people who were seeing where the future was going to be, and other people didn’t get it. Eventually — eventually — we’d be right, but who knows exactly when.”

That is from Keach Hagey’s The Optimist: Sam Altman, OpenAI, and the Race to Invent the Future, which I very much enjoyed. I am not sure Robin’s supply of parties has been increasing out here in northern Virginia…

Changes in the College Mobility Pipeline Since 1900

By Zachary Bleemer and Sarah Quincy:

Going to college has consistently conferred a large wage premium. We show that the relative premium received by lower-income Americans has halved since 1960. We decompose this steady rise in ‘collegiate regressivity’ using dozens of survey and administrative datasets documenting 1900–2020 wage premiums and the composition and value-added of collegiate institutions and majors. Three factors explain 80 percent of collegiate regressivity’s growth. First, the teaching-oriented public universities where lower-income students are concentrated have relatively declined in funding, retention, and economic value since 1960. Second, lower-income students have been disproportionately diverted into community and for-profit colleges since 1980 and 1990, respectively. Third, higher-income students’ falling humanities enrollment and rising computer science enrollment since 2000 have increased their degrees’ value. Selection into college-going and across four-year universities are second-order. College-going provided equitable returns before 1960, but collegiate regressivity now curtails higher education’s potential to reduce inequality and mediates 25 percent of intergenerational income transmission.

An additional hypothesis is that these days the American population is “more sorted.” We no longer have the same number of geniuses going to New York city colleges, for instance. Here is the full NBER paper.

Has Buddhism been statist for a long time?

Again, as was also the case in so many Buddhist countries, the success of Buddhism relied heavily on its connections to the court. In Korea, the tradition of “state protection Buddhism” was inherited from China. Here, monarchs would build and support monasteries and temples, where monks would perform rituals and chant sutras intended to both secure the well-being of the royal family, in this life and the next, and protect the kingdom from danger, especially foreign invasion.

…As in China, the Korean sangha remained under the control of the state; offerings to monasteries could only be made with the approval of the throne; men could only become monks on “ordination platforms” approved by the throne; and an examination system was established that placed monks in the state bureaucracy. As in other Buddhist lands, monks were not those who had renounced the world but were vassals of the king, with monks sometimes dispatched to China by royal decree. With strong royal patronage, Buddhism continued to thrive through the Koryo period (935-1392), with monasteries being granted their own lands and serfs, accumulating great wealth in the process.

That is an excerpt from Donald S. Lopez, Jr. Buddhism: A Journey through History, an excellent book. Maybe the best book on the history of Buddhism I have read? And one of the very best books of this year.

Covid sentences to ponder

Tim Vanable: I wonder about the tenability of ascribing a policy like extended school closures to a “laptop class.” Support for school reopenings did not fall neatly along educational lines. The parents most reluctant to send their kids back to school in blue cities in the spring of 2021 were black and Hispanic, research has consistently found, not white. And the most organized opposition to school reopenings, as you know, came from teachers’ unions, who can hardly be considered stormtroopers of the managerial elite.

Should gdp include defense spending?

Maybe not, isn’t that a form of double counting? After all, defense spending is there to enable the production of other goods and services, it is not useful per se. Chandler S. Reilly and Vincent Geloso recalculate the history of U.S. economic growth using this new method:

In fact, our corrections applied to the entire period from 1790 to today show new key facts. Our corrected GDP series reveals that the first half of the 20th century, rather than showcasing robust growth, emerges as a prolonged period of stagnation interrupted by crises. The economy, which had grown at an exceptional pace from 1865 to 1913, gradually deviated from this path between 1913 and 1950. Many claim that this deviation only occurred during the Great Depression and that it ended during the Thirty Glorious years after. But our corrected series show that America never returned to its exceptional growth path.

Finally, pairing our corrected GDP with historical income distribution (i.e., inequality) data reshapes the narrative of the “Great Leveling” during the mid-twentieth century and particularly during wartime years. The leveling, traditionally celebrated as a period of diminishing inequality, actually coincided with declining living standards for everyone — even the wealthy.

Recommended, read it here, of real importance.

Sentences to ponder

In fact, it was the Obama administration that paused funding for high-risk GoF studies in 2014. The ban was lifted by none other than Donald Trump in 2017. At the time, outlets like Scientific American and Science covered the decision, in articles that quoted scientists talking about what could go wrong. Remind yourself of this the next time you see rightists trumpeting some headline showing the media being wrong about something.

That is from Richard Hanania’s Substack.

Adam Smith on Mercantilism

ChatGPT: Adam Smith strongly criticized mercantilism in The Wealth of Nations (1776), arguing that it was a flawed and self-defeating economic doctrine. His main points:

-

Wealth is not gold: Mercantilists equated national wealth with the accumulation of gold and silver (bullion). Smith rejected this, emphasizing instead that real wealth lies in a nation’s productive capacity—its ability to produce goods and services.

-

Trade is not zero-sum: Mercantilists saw international trade as a zero-sum game where one nation’s gain is another’s loss. Smith argued trade is mutually beneficial. He introduced the idea of absolute advantage, showing how specialization and exchange increase the wealth of all nations.

-

Protectionism hurts consumers: Mercantilist policies favored domestic producers through tariffs and trade restrictions. Smith viewed these as harmful to consumers, who are forced to pay higher prices and have fewer choices. He famously wrote:

“Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production; and the interest of the producer ought to be attended to, only so far as it may be necessary for promoting that of the consumer.”

-

Cronyism and rent-seeking: Smith accused mercantilist policies of serving powerful interest groups (e.g., guilds, monopolies, chartered trading companies) at the expense of the public. He viewed the system as corrupted by lobbying and state favoritism:

“The interest of the dealers… in any particular branch of trade or manufactures, is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public.”

-

Free trade promotes growth: Smith advocated for a liberal trade regime based on natural liberty. He saw the division of labor and free exchange as key drivers of economic growth and prosperity.

In short, Smith saw mercantilism as a doctrine that enriched special interests and weakened overall prosperity. He called for a shift toward a system where markets and competition—not state-backed monopolies—allocate resources efficiently.

Has Clothing Declined in Quality?

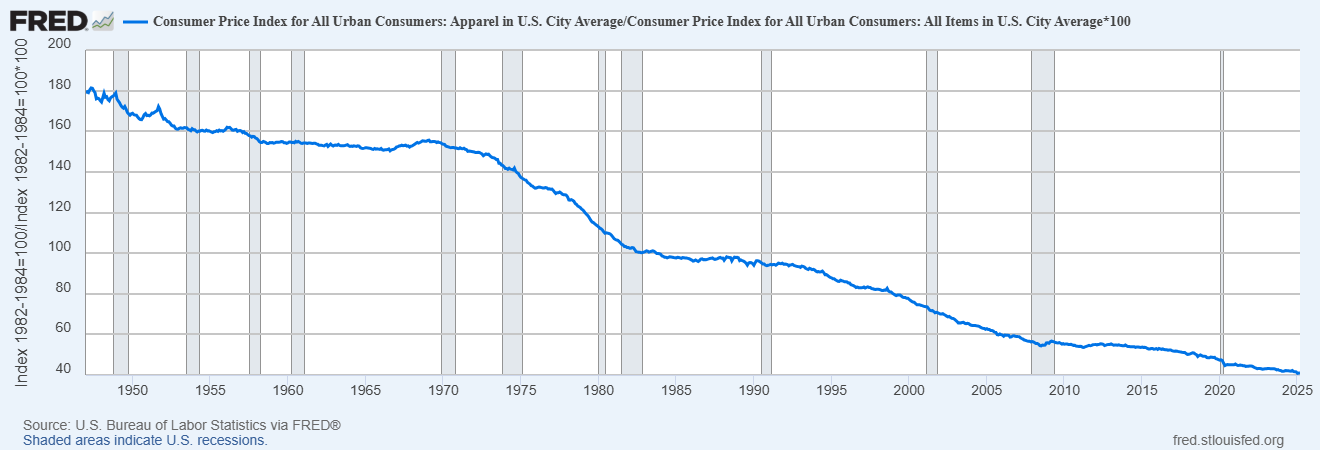

The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) recently tweeted that they wanted to bring back apparel manufacturing to the United States. Why would anyone want more jobs with long hours and low pay, whether historically in the US or currently in places like Bangladesh? Thanks in part to international trade, the real price of clothing has fallen dramatically (see figure below). Clothing expenditure dropped from 9-10% of household budgets in the 1960s (down from 14% in 1900) to about 3% today.

Apparently, however, not everyone agrees. While some responses to my tweet revealed misunderstandings of basic economics, one interesting counter-claim emerged–the low price of imported clothing has been a false bargain, the argument goes, because the quality of clothing has fallen.

The idea that clothing has fallen in quality is very common (although it’s worth noting that this complaint was also made more than 50 years ago, suggesting a nostalgia bias, like the fact that the kids today are always going to hell). But are there reliable statistics documenting a decline in quality? In some cases, there are! For example, jeans from the 1960s-80s, for example, were often 13–16 oz denim, compared to 9–11 oz today. According to some sources, the average garment life is down modestly. The statistical evidence is not great but the anecdotes are widespread and I shall accept them. Most sources date the decline in quality to the fast fashion trend which took off in the 1990s and that provides a clue to what is really going on.

Fast fashion, led by firms like Zara, is a business model that focuses on rapidly transforming street style and runway trends into mass-produced, low-cost clothing—sometimes from runway to store within weeks. The model is not about timeless style but about synchronized consumption: aligning production with ephemeral cultural signals, i.e. to be fashionable, which is to say to be on trend, au-courant and of the moment.

It doesn’t make sense to criticize fast fashion for lacking durability—by design, it isn’t meant to last. Making it durable would actually be wasteful. The product isn’t just clothing; it’s fashionable clothing. And in that sense, quality has improved: fast fashion is better than ever at delivering what’s current. Critics who lament declining quality miss the point—it’s fun to buy new clothes and if consumers want to buy new clothes it doesn’t make sense to produce long lasting clothes. People do own many more pieces of clothing today than in the past but the flow is the fun.

So my argument is that the decline in “quality” clothing has little to do with the shift to importing but instead is consumer-driven and better understood as an increase in the quality of fashion. Testing my theory isn’t hard. Consider clothing where function, not just fashion, is paramount: performance sportswear and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

There has been a massive and obvious improvement in functional clothing. The latest GoreTex jackets, for example, are more than five times as water resistant (28 000 mm hydrostatic head) compared to the best waxed cotton technology of the past (~5 000 mm) and they are breathable (!) and lighter. Or consider PolarTec winter jackets, originally developed for the military these jackets have the incredible property of releasing heat when you are active but holding it in when you are inactive. (In the past, mountain climbers and workers in extreme environments had to strip on or off layers to prevent over-heating or freezing while exerting effort or resting.) Amazing new super shoes can actually help runners to run faster! Now that is high quality. Personal protective equipment has also increased in quality dramatically. Industrial workers and intense sports enthusiasts can now wear impact resistant gloves which use non-Newtonian polymers that stiffen on impact to reduce hand injuries.

Moreover, it’s not just functional clothing that has increased in quality. For those willing to look, there is in fact plenty of high-quality clothing readily available. From Iron Heart, for example, you can buy jeans made with 21oz selvedge indigo denim produced in Japan. Pair with a high-quality Ralph Lauren shirt, a Mackinaw Wool Cruiser Jacket and a nice pair of Alden boots. Experts like the excellent Derek Guy regularly highlight such high-quality options. Of course, when Derek Guy discusses clothes like this people complain about the price and accuse him of being an elitist snob. Sigh. Tradeoffs are everywhere.

Moreover, it’s not just functional clothing that has increased in quality. For those willing to look, there is in fact plenty of high-quality clothing readily available. From Iron Heart, for example, you can buy jeans made with 21oz selvedge indigo denim produced in Japan. Pair with a high-quality Ralph Lauren shirt, a Mackinaw Wool Cruiser Jacket and a nice pair of Alden boots. Experts like the excellent Derek Guy regularly highlight such high-quality options. Of course, when Derek Guy discusses clothes like this people complain about the price and accuse him of being an elitist snob. Sigh. Tradeoffs are everywhere.

Critics long for a past when goods were cheap, high quality, and Made in America—but that era never really existed. Clothing in the past was more expensive and often low quality. To the extent that some products in the past were of higher quality–heavier fabric jeans, for example–that was often because the producers of the time couldn’t produce it less expensively. Technology and trade have increased variety along many dimensions, including quality. As with fast fashion, lower quality on some dimensions can often produce a superior product. And, of course, it should be obvious but it needs saying: products made abroad can be just as good—or better—than those made domestically. Where something is made tells you little about how well it’s made.

The bottom line is that international trade has brought us more options and if today’s household were to redirect the historical 9 – 10 % share of income to clothing, it could absolutely buy garments that are heavier, better-constructed, and longer-lived than the typical mid-century mass-market clothing.

Lady Liberty of the Pacific

Instead of re-opening Alcatraz as super-max prison we should build a statue to America. I suggest “Lady Liberty of the Pacific”. The spirit of Columbia ala John Gast’s American Progress carrying a welcoming beacon-lamp in her raised right hand and a coiled fibre-optic cable in her left representing Bay Area technology.

What Should Classical Liberals Do?

My little contretemps with Chris Rufo raises the issue of what should classical liberals do? In a powerful essay, C. Bradley Thompson explains why the issue must be faced:

The truth of the matter is that the Conservative-Libertarian-Classical Liberal Establishment gave away and lost an entire generation of young people because they refused to defend them or to take up the issues that mattered most to them, and in doing so the Establishment lost America’s young people to the rising Reactionary or Dissident Right, by which I primarily mean groups such as the so-called TradCaths or Catholic Integralists and the followers of the Bronze Age Pervert. (See my essay on the reactionary Right, “The Pajama-Boy Nietzscheans.”)

I do not think Mr. Rufo would disagree with me on this point, but he has not quite made it himself either (at least not as far as I know), so I will make it in my own name.

The betrayal, abandonment, desertion, and loss of America’s young people by conservative and libertarian Establishmentarians can be understood with the following hypothetical.

Imagine the plight of, let us say, a 23-year-old young man in the year 2016. Imagine that he’s been told every single day from kindergarten through the end of college that he’s racist, sexist, and homophobic by virtue of being white, male, and heterosexual. Further imagine that he was falsely diagnosed by his teachers in grade school with ADD/ADHD and put on Ritalin because, well, he’s an active boy. And then his teachers tell him when he’s 12 that he might not actually be a boy, but rather that he might be a girl trapped in boy’s body. And let us also not forget that he’s also been told by his teachers and professors that the country his parents taught him to love was actually founded in sin and is therefore evil. To top it all off: he didn’t get into the college and then the law school of his choice despite having test scores well above those who did.

In other words, what this oppressed and depressed young man has experienced his whole life is a cultural Zeitgeist defined by postmodern nihilism and egalitarianism. These are the forces that are ruining his life and making him miserable.

Let’s also assume that said young man is also temperamentally some kind of conservative, libertarian, or classical liberal, and he interns at the Heritage Foundation, the Cato Institute, or the Institute for Humane Studies hoping to find solace, allies, and support to give relief to his existential maladies.

And how does Conservatism-Libertarianism Inc. respond to what are clearly the dominant cultural issues of our time?

Well, the Establishment publishes yet another white paper on free-market transportation or energy policy. The Heritage Foundation doubles down on more white papers on deficits and taxation policy. The Cato Institute churns out more white papers on legalizing pot and same-sex marriage. The Institute for Humane Studies goes all in to sit at the cool kids’ lunch table by ramping up its videos on spontaneous order featuring transgender 20-somethings.

Is it any wonder that today’s young people who have suffered the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune are stepping outside the arc of history yelling, “stop”? At a certain point, these young people let out a collective primal scream, shouting “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore.” And when the “youf” (as they refer to themselves online) realized that Establishment conservatives and libertarians did not hear them and lacked the vocabulary, principles, power, and courage to defend them from their Maoist persecutors, they went underground to places like 4chan, 8chan, and various other online discussion boards, where they found a Samizdat community of the oppressed.

Having effectively abandoned late-stage Millennials and Gen Z, Conservatism and Libertarianism Inc. should not be surprised, then, that today’s young people who might be otherwise sympathetic to their policies have left that world and become radicalized. News flash: Gen Z is attracted to people who are willing to defend them and attack social nihilism and egalitarianism in all their forms.

Hence the rise of what I call the “Fight Club Right,” which calls for a new kind of American politics. Gen Z rightism is done with what they call the Boomer’s “fake and ghey” attachment to the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the institutions of the Constitution. In fact, many young people who have migrated to the reactionary Right have openly and repeatedly rejected the principles of the American founding as irrelevant in the modern world.

More to the point, this younger generation is done with the philosophy of losing. They’re certainly done with the Establishment. They also seem to be done with classical liberalism and the American founding. (This is a more complicated topic.) Instead, what they want is political power to punish their enemies and to take over the “regime.” They want to use the coercive force of the State to create their new America.

…Conservatism and Libertarianism Inc. seemed utterly oblivious to the fact that the Left had pivoted and changed tactics after the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. By the 1990s, the Left had abandoned economic issues and the working class and was doubling down on cultural issues. Rather than trying to take over the trade-union movement, for instance, the postmodern Left went for MTV and the Boy Scouts, while the major DC think tanks on the Right went for issues too distant from the lives of young people such as the deficit, taxation, and regulatory policy.

While socialism continues to be the end of the Left, the means to the end is postmodern nihilism. That’s where the Left planted its flag and that’s the terrain that it has occupied without opposition, whereas conservative and libertarian organizations such as the Heritage Foundation and the Cato Institute were fighting for ideological hegemony in the economic realm. Between 2000 and 2025, cultural nihilism and its many forms and manifestations is where the action is and has been for a quarter century. So powerful has postmodern nihilism become that even some left-wing “libertarian” organizations have simply become left-wing.

What should I ask Annie Jacobsen?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with her. From Wikipedia:

Annie Jacobsen (born June 28, 1967) is an American investigative journalist, author, and a 2016 Pulitzer Prize finalist. She writes for and produces television programs, including Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan for Amazon Studios, and Clarice for CBS. She was a contributing editor to the Los Angeles Times Magazine from 2009 until 2012.

Jacobsen writes about war, weapons, security, and secrets. Jacobsen is best known as the author of the 2011 non-fiction book Area 51: An Uncensored History of America’s Top Secret Military Base, which The New York Times called “cauldron-stirring.”[ She is an internationally acclaimed and sometimes controversial author who, according to one critic, writes sensational books by addressing popular conspiracies.

I very much liked her book Nuclear War: A Scenario. Do read the Wikipedia entry for a full look at what she has written. So what should I ask her?