Category: History

Innovation and the Great Divergence

Abstract: Recent developments in historical national accounting suggest that the timing of the Great Divergence hinges on the different trends in northwest Europe and the Yangzi Delta region of China. The positive trend of GDP per capita in northwest Europe after 1700 was a continuation of a process that began in the fourteenth century, while the negative trend in the Yangzi Delta continued a pattern of alternating periods of growing and shrinking, but reaching a new lower level. These GDP per capita trends were driven by different paths of innovation. TFP growth was strongly positive in Britain after the Black Death, in the Netherlands during the sixteenth century and again in Britain from the mid-seventeenth century. Although TFP growth was positive in China during the Northern Song dynasty, it was predominantly negative during the Ming and Qing dynasties, in the Yangzi Delta as well as in China as a whole.

By Stephen Broadberry and Runzhuo Zhai, via the excellent Samir Varma.

Reading Orwell in Moscow

In this paper, I measure the effect of conflict on the demand for frames of reference, or heuristics that help individuals explain their social and political environment by means of analogy. To do so, I examine how Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 reshaped readership of history and social science books in Russia. Combining roughly 4,000 book abstracts retrieved from the online catalogue of Russia’s largest bookstore chain with data on monthly reading patterns of more than 100,000 users of the most popular Russian-language social reading platform, I find that the invasion prompted an abrupt and substantial increase in readership of books that engage with the experience of life under dictatorship and acquiescence to dictatorial crimes, with a predominant focus on Nazi Germany. I interpret my results as evidence that history books, by offering regime-critical frames of reference, may serve as an outlet for expressing dissent in a repressive authoritarian regime.

That is from a job market paper by Natalia Vasilenok, political science at Stanford. Via.

What of American culture from the 1940s and 1950s deserves to survive?

In the comments, Elijah asks:

Would love to read a post about which movies and novels from this era do and do not deserve to survive and why.

I do not love 20th century American fiction, so maybe I am the wrong person to ask. I started with GPT-5, which gave this list of novels from those two decades. I’ve read a significant percentage of those, and would prefer:

Raymond Chandler, J.D. Salinger, Nabokov, Patricia Highsmith, Shirley Jackson, and lots of science fiction. The I, Robot stories are from the 1940s, and the book published in 1950. A lot of the “more serious” entries on that list I feel have diminished somewhat with age.

Great Hollywood movies from that era are too numerous to name. In music there is plenty of jazz, plus Elvis, Chuck Berry, James Brown, Buddy Holly, doo wop, “the roots of rock” (includes some one hit wonders), Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, the Everlies, the Louvin Brothers, Johnny Cash, lots of country and bluegrass and blues, and many other very well known names from the 1950s. It is one of the most seminal decades for music ever. The 1940s are worse, perhaps because of the war, but still there is Rodgers and Hammerstein, lots of big band, and Woody Guthrie.

Contra Ted Gioia, much of that remains well-known to this day, though I would admit Howard Hanson and Walter Piston have fallen by the wayside. Overall, I think we are processing the American past pretty well.

The Industrial Revolution in the United States: 1790-1870

This chapter explores the distinctive trajectory of American industrialization up to 1870, emphasizing how the United States adapted and transformed British technologies to suit its unique economic and resource conditions. Rather than a straightforward transfer of innovations, the chapter argues that American industrial development was shaped by path-dependent processes and historical contingencies—such as the Embargo Act of 1807 and government sponsorship of firearms production—that enabled the emergence of a domestic innovation ecosystem. The chapter offers fresh insights into how high-pressure steam engines, vertically integrated textile mills, and precision manufacturing techniques evolved in response to labor scarcity, capital constraints, and abundant natural resources. A particularly novel contribution is the detailed analysis of how American manufacturers substituted mechanization and organizational innovation for skilled labor, leading to the development of technologies that were not only distinct from their British counterparts but also foundational for the Second Industrial Revolution. The chapter also highlights the democratization of invention, showing how economic incentives and institutional support fostered widespread innovation among ordinary citizens. By integrating technological, economic, and institutional perspectives, this chapter provides a compelling explanation for why the United States developed a robust manufacturing sector despite seemingly unfavorable initial conditions.

That is from a recent NBER working paper by Joshua L. Rosenbloom.

Academic Human Capital in European Countries and Regions, 1200-1793

We present new annual time-series data on academic human capital across Europe from 1200 to 1793, constructed by aggregating individual-level measures at three geographic scales: cities, present-day countries (as of 2025), and historically informed macro-regions. Individual human capital is derived from a composite index of publication outcomes, based on data from the Repertorium Eruditorum Totius Europae (RETE) database. The macro-regional classifications are designed to re ect historically coherent entities, offering a more relevant perspective than modern national boundaries. This framework allows us to document key patterns, including the Little Divergence in academic human capital between Northern and Southern Europe, the effect of the Black Death and the Thirty Years’ War on academic human capital, the respective contributions of academies and universities, regional inequality within the Holy Roman Empire, and the distinctiveness of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Here is the full paper by Matthew Curtisa, David de la Croix, Filippo Manfredinib, and Mara Vitale. Via the excellent Samir Varma.

My excellent Conversation with David Commins

Saudi Arabia and the Gulf are the topics, here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

David Commins, author of the new book Saudi Arabia: A Modern History, brings decades of scholarship and firsthand experience to explain the kingdom’s unlikely rise. Tyler and David discuss why Wahhabism was essential for Saudi state-building, the treatment of Shiites in the Eastern Province and whether discrimination has truly ended, why the Saudi state emerged from its poorer and least cosmopolitan regions, the lasting significance of the 1979 Grand Mosque seizure by millenarian extremists, what’s kept Gulf states stable, the differing motivations behind Saudi sports investments, the disappointing performance of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology despite its $10 billion endowment, the main barrier to improving its k-12 education, how Yemen became the region’s outlier of instability and whether Saudi Arabia learned from its mistakes there, the Houthis’ unclear strategic goals, the prospects for the kingdom’s post-oil future, the topic of David’s next book, and more.

And an excerpt:

COWEN: Now, as you know, the senior religious establishment is largely Nejd, right? Why does that matter? What’s the historical significance of that?

COMMINS: Right. Nejd is the region of central Arabia. Riyadh is currently the capital. The first Saudi empire had a capital nearby, called Diriyah. Nejd is really the territory that gave birth to the Wahhabi movement, it’s the homeland of the Saud dynasty, and it is the region of Arabia that was most thoroughly purged of the older Sunni tradition that had persisted in Nejd for centuries.

Consequently, by the time that the Saudi government developed bureaucratic agencies in the 1950s and ’60s, the religious institution was going to recruit from that region of Arabia primarily. Now, it certainly attracted loyalists from other parts of Arabia, but the Wahhabi mission, as I call it — their calling to what they considered true belief — began in Nejd and was very strongly identified with the towns of Nejd ever since the late 1700s.

COWEN: Would I be correct in inferring that some of the least cosmopolitan parts of Saudi Arabia built the Saudi state?

COMMINS: Yes, that is correct. That is correct. If you think of the 1700s and 1800s, the Red Sea and Persian Gulf coast of Arabia were the most cosmopolitan parts of Arabia.

COWEN: They’re richer, too, right? Jeddah is a much more advanced city than Riyadh at the time.

COMMINS: Somewhat more advanced. Yes, it is more advanced, it is more cosmopolitan than Nejd. There is the regional identity in Hejaz, that is the Red Sea coast where the holy cities and Jeddah are located. The townspeople there tended to look upon Nejd as a less advanced part of Arabia. But again, that’s a very recent historical development.

COWEN: How is it that the coastal regions just dropped the ball? You could imagine some alternate history where they become the center of Saudi power and religious thought, but they’re not.

COMMINS: Right. If you take Jeddah, Mecca, and Medina — that region of Arabia, known as Hejaz, had always been under the rule of other Muslim empires. They were under the rule of other Muslim powers because of the religious value of possessing, if you will, the holy cities, Mecca and Medina. From the time of the first Muslim dynasty that was based in Damascus in the seventh and early eighth centuries, all the way until the Ottoman Empire, Muslim dynasties outside Arabia coveted control of that region. They were just more powerful than local resources could generate.

Hejaz was always, if you were, to dependency on outside Muslim powers. If you look at the east coast of Arabia — what’s now the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf — it was richer than central Arabia. It’s the largest oasis in Arabia. It is in proximity to pearling banks, which were an important source for income for residents there. It was part of the Indian Ocean trade between Iraq and India. The population there was always — well, always — for the last thousand years has been dominated by Bedouin tribesmen.

There was a brief Ismaili Shia republic, you might say, in that part of Arabia in medieval times. It just didn’t have, it seems, the cohesion to conquer other parts of Arabia. That’s what makes the Saudi story really remarkable, is that they were able to muster and sustain the cohesion to carry out a conquest like that over the course of 50 years.

COWEN: Physically, how did they manage that? Water is a problem, a lot of transport is by camel, there’s no real rail system, right?

Recommended, full of historical information about a generally neglected region, neglected from the point of view of history at least rather than current affairs.

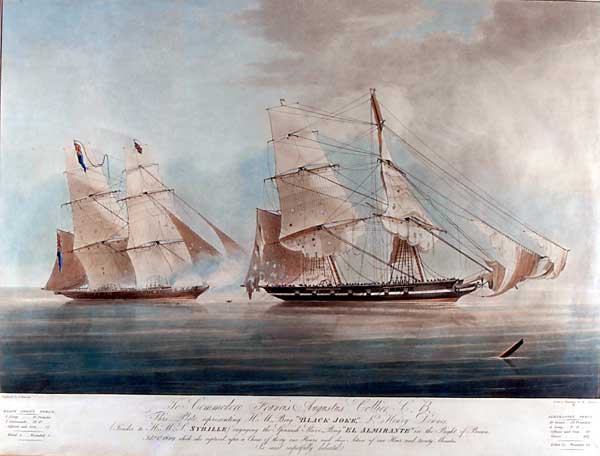

The British War on Slavery

In August of 1833 the British passed legislation abolishing slavery within the British Empire and putting more than 800,000 enslaved Africans on the path to freedom. To make this possible, the British government paid a huge sum, £20 million or about 5% of GDP at the time, to compensate/bribe the slaveowners into accepting the deal. In inflation adjusted terms this is about £2.5 billion today (2025) but relative to GDP the British spent an equivalent of about $170 billion to free the slaves, a very large expenditure.

Indeed, the expenditure was so large that the money was borrowed and the final payments on the debt were not made until 2015. When in 2015 a tweet from the British Treasury revealed this surprising fact, there was a paroxysm of outrage as if slaveholders were still being paid off. I see the compensation in much more positive terms.

Of course, in an ideal world, compensation would have been paid to the slaves, not the slaveowners. Every man has a property in his own person and it was the slaves who had had their property stolen. In an ideal world, however, slavery would never have happened. Thus, the question the British abolitionists faced is not what happens in an ideal world but how do we get from where we are to a better world? Compensating the slaveowners was the only practical and peaceful way to get to a better world. As the great abolitionist William Wilberforce said on his deathbed “Thank God that I should have lived to witness a day in which England is willing to give twenty millions sterling for the abolition of slavery!”

The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act was preceded by the 1807 Slave Trade Act which had banned trade in slaves. In an excellent new paper, The long campaign: Britain’s fight to end the slave trade, economist historians Yi Jie Gwee and Hui Ren Tan assemble new archival data to assess how the Royal Navy’s anti slave-trade patrols expanded over time, how effective they were at curtailing the trade, the influence of supply-side enforcement versus demand-side changes on ending the trade, and why Britain persisted with this costly campaign.

Britain’s naval suppression campaign began on a modest scale but the campaign grew in strength throughout the 19th century, peaking in the late 1840s to early 1850s when over 14% of the entire Royal Navy fleet was deployed to anti-slavery patrols. The British patrols captured some 1,600 ships and freed some 150,000 people destined for slavery but they were at best only modestly successful at reducing the slave trade. The big impact came when Brazil, the largest remaining market for enslaved labor (by the mid-19th century, nearly 80% of trans-Atlantic slave voyages sailed under Brazilian or Portuguese flags), enacted its anti slave-trade law in 1850. Britain’s campaign was not without influence on the demand side however as passage of the Aberdeen Act in 1845 allowed the Royal Navy to seize Brazilian slave ships and that put pressure on Brazil and helped spur the 1850 law.

The suppression patrols were expensive (consuming ships, men, and funds), and Britain derived no direct economic benefit from them. Yet, even during the Napoleonic Wars, the Opium Wars, and the Crimean War, the Royal Navy continued to station ships, even high-tech steam ships, off West Africa to catch slavers. Due to the expense, the patrols were controversial and there were attempts to end them. Gwee and Tan look at the votes on ending the patrols and find that ideology was the dominant factor explaining support for the patrols, that is a principled opposition to the slave trade and a belief in the moral cause of abolition kept Britain in the war against slavery even at considerable expense.

Ordinarily, I teach politics without romance and look for interest as an explanation of political action and while I don’t doubt that doing good and doing well were correlated, even during abolition, I also agree with Gwee and Tan that the British war on slavery was primarily driven by ideology and moral principle as both the compensation plan and the support of the anti-slavery patrols attest.

British taxpayers shouldered an enormous military and financial burden to eliminate slavery, reflecting a generosity of spirit and a sincere attempt to address a moral wrong—an act of atonement that stands as one of the most unusual and significant in history.

Patrick Collison on the Irish Enlightenment

Most of all, the Irish Enlightenment seems to me an instance of small group theory. I’m fond of the thought that between great man and structuralist theories of history there lies an intermediate position: the small group, a colocated cauldron for iconoclastic thinking, can as a collective pioneer a novel direction. The romantics in Jena, the founders of Silicon Valley, the musicians behind punk. Unsurprisingly, the early Irish thinkers are closely connected. Swift and Berkeley attended the same school and were good friends. Hutcheson and Berkeley debated publicly, while Burke’s work is clearly downstream of Hutcheson’s.

And this:

How should we view the movement as a whole? Well, the timing is important: Cantillon published his Essai in 1755, Swift Drapier’s Letters in 1724, and Berkeley The Querist in 1735. It seems to me that, before 1750, the Irish thinkers have a strong claim to leading the world in the field of economics and to having collectively sketched out much of the core of the field in broadly correct terms. In Petty you have economic statistics; in Cantillon you have risk, market pricing, and much else; in Berkeley, you have a theory of national banking plus development economics; in Swift you have proto-monetarism. The claim is not that they figured everything out or were right on all points, but which other school or group could you rank ahead of them? Smith published Wealth of Nations in 1776 and The French physiocrats, who were very important, came later: Quesnay’s first piece wasn’t published until 1756.

Do read the whole short essay.

What should I ask Jonny Steinberg?

Yes I will be doing a Conversation with him. From Wikipedia:

Steinberg was born and raised in the northern suburbs of Johannesburg, South Africa. He was educated at Wits University in Johannesburg, and at the University of Oxford, where he was a Rhodes Scholar and earned a doctorate in political theory. He taught for nine years at Oxford, where he was Professor of African Studies. He currently teaches at Yale University‘s Council on African Studies.

Three of Steinberg’s books – Midlands (2002), about the murder of a white South African farmer, The Number (2004), a biography of a prison gangster, and Winnie & Nelson (2023) – won South Africa’s premier non-fiction prize, the Sunday Times CNA Literary Awards making him the first writer to win it three times.

I am a special fan of Winnie & Nelson, which I consider to be one of the best books of the last ten years. He is currently working on a biography of Cecil Rhodes. So what should I ask him?

Could China Have Gone Christian?

The Taiping Rebellion is arguably the most important event in modern history that even educated Westerners know very little about. It’s also known as the Taiping Civil War and it was one of the largest conflicts in human history (1850–1864), with death toll estimates ranging from 20 to 30 million, far exceeding deaths in the US civil war (~750,000) with which it overlapped. The civil war destabilized Qing China, weakening it against foreign powers and shaped the trajectory of 19th- and 20th-century Chinese politics. In China the Taiping Civil War is considered the defining event of the 19th-century.

The most surprising aspect of the civil war is that the rebels were Christian. The rebellion has its genesis in 1837 with the dramatic visions of Hong Xiuquan. In his visions, Hong and his elder brother traveled the world slaying demons, guided onwards by an old man who berated Confucius for failing to teach proper doctrines to the Chinese people. (I draw here on Steven Platt’s excellent Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom). It is perhaps not coincidental that Hong began experiencing his visions after failing the infamously stressful Chinese civil service exams for the third time. It wasn’t until 1843, however, after he failed the exams for the fourth time, that he had an epiphany. A Christian tract that he had never read before suddenly unlocked the meaning of his visions–the elder brother was Jesus Christ, making Hong the second son of the old man, God.

With his visions unlocked, Hong threw himself into learning and then teaching the Gospels. He quickly converted his cousin and a neighbor and they baptized themselves and began taking down icons of Confucianism at their local school. Confucianism, of course, underpinned the exam system that Hong had grown to hate (Recall, that a similar pattern is visible in India today, where mass exams generate large numbers of educated but frustrated youth).

The wild visions of a lowly scholar wouldn’t seem to have the makings of a revolutionary movement but this was the beginning of the century of humiliation when China was forced to confront the idea that far from being the center of civilization it was in fact a backward and weak power on the world stage. Moreover, China was governed by foreigners, the Manchus, who despite ruling for 200 years had never really integrated with the Chinese population. Hence, Hong’s calls to kill the demons merged with a nationalist fervor to massacre the Manchus. Hong proclaimed himself the Heavenly King and his movement quickly grew to more than a million zealous warriors who captured significant territory including establishing the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom with its capital at Nanjing.

The regime banned foot‑binding, prostitution and slavery, promoted the equality of men and women, distributed bibles, and instituted a 7-day week with strict observance of the sabbath. To be sure, this was a Sinicized, millenarian Christianity, more Old Testament than new but the Christianity was serious and real and the rebels appealed to British and Americans as their Christian brothers. One Taiping commander wrote to a British counterpart:

You and I are both sons of the Heavenly Father, God, and are both younger brothers of the Heavenly Elder Brother, Jesus. Our feelings towards each other are like those of brothers, and our friendship is as intimate as that of two brothers of the same parentage. (quoted in Platt p.40)

Now, as it happened, the Heavenly Kingdom fell to the Qing, but it was a close thing and could easily have gone the other way. Western powers—above all Britain, but also the United States—hedged their bets and at times fought both sides, yet for short-sighted reasons ultimately tilted toward the Qing, an intervention Ito Hirobumi later called “the most significant mistake the British ever made in China.” Internal purges fractured the movement, alliances went unmade, and crucial opportunities slipped away. Yet the moment was pregnant with possibility. Hong Rengan, Hong Xiuquan’s cousin and prime minister from 1859, pushed sweeping modernization: railroads, steamships, postal services, banks, and even democratic reforms. These initiatives would likely have brought what one might call Christianity with Chinese Characteristics into closer alignment with Western Christianity.

Indeed, it is entirely plausible that with only a few turns of history, China might now be the world’s most populous Christian nation. And if that seems hard to believe, consider what did happen. Sixty three years after the fall of Nanjing in 1864, China again erupted into civil war under Mao Zedong. This time the rebels triumphed, and instead of a Christian Heavenly Kingdom the world got a Communist People’s Republic. The parallels are striking: both Hong and Mao led vast zealous movements that promised equality, smashed tradition, and enthroned a single man as the embodiment of truth. Both drew on foreign creeds—Hong from Protestant Christianity, Mao from Marxism-Leninism. Both movement had excesses but of the counter-factual and the factual I have little doubt which promised more ruin. The Heavenly Kingdom pointed toward a biblical moral order aligned with the West, the People’s Republic toward a creed that delivered famine, purges, and economic stagnation. Such are the contingencies of history—an ill-timed purge in Nanjing, a foreign gunboat at Shanghai, a missed alliance with the Nian. Small events cascaded into vast consequences. For the want of a nail, the Heavenly Kingdom was lost, and with it perhaps an entirely different modern world.

How well did Katrina reconstruction go?

…the federal government did something extraordinary: It committed more than $140 billion toward the region’s recovery. Adjusted for inflation, that’s more than was spent on the post-World War II Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe or for the rebuilding of Lower Manhattan after the Sept. 11 attacks. It remains the largest post-disaster domestic recovery effort in U.S. history…

Today, New Orleans is smaller, poorer and more unequal than before the storm. It hasn’t rebuilt a durable middle class, and lacks basic services and a major economic engine outside of its storied tourism industry.

The core problem was the inability to turn abundant resources into a clear vision backed by political will. Federal dollars were funneled into a maze of state agencies and local governments with clashing priorities, vague metrics and near-zero accountability. Billions went to contractors and government consultants services such as schools, transit, health care and housing were neglected. For example, one firm, ICF International, received nearly $1 billion to administer Road Home, the oft-criticized state program to rebuild houses.

Here is more from Mark F. Bonner and Mathew D. Sanders at the NYT.

My biographical podcast with Joshua Rosen

Joshua writes me:

It came out great.

Here it is on Apple: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/formative-figures/id1809832335?i=1000723588104

Here it is on Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/episode/5q5rnjcQTLASL438hI6s3c?si=YWB2sduVRmiCV0TUrSRSHg

Lots of fun for me, mostly tales of childhood and the like.

Did the United States grow its way out of WWII debt?

Not as much as you might think:

ABSTRACT: The fall in the U.S. public debt/GDP ratio from 106% in 1946 to 23% in 1974 is often attributed to high rates of economic growth. This paper examines the roles of three other factors: primary budget surpluses, surprise inflation, and pegged interest rates before the Fed-Treasury Accord of 1951. Our central result is a simulation of the path that the debt/GDP ratio would have followed with primary budget balance and without the distortions in real interest rates caused by surprise inflation and the pre-Accord peg. In this counterfactual, debt/GDP declines only to 74% in 1974, not 23% as in actual history. Moreover, the ratio starts rising again in 1980 and in 2022 it is 84%. These findings imply that, over the last 76 years, only a small amount of debt reduction has been achieved through growth rates that exceed undistorted interest rates.

That is from a recent paper by Julien Acalin and Laurence Ball. Via the excellent Samir Varma.

The history of American corporate nationalization

I wrote this passage some while ago, but never published the underlying project:

The American Constitution is hostile to nationalization at a fundamental level. The Fifth Amendment prohibits government “takings” without just compensation to the owners, and that is sometimes called the “takings clause.” Since the United States did not start off with a large number of state-owned enterprises, there is no simple and legal way for the country to get from here to there. Government nationalization of private companies would prove expensive, most of all to the government itself. More importantly, the strength of American corporate interests has taken away any possible pressures to eliminate or ignore this amendment.

The lack of interest in state-owned enterprises reflects some broader features of the United States, most of all a kind of messiness and pluralism of control. An extreme federalism has bred a large number of regulators at federal, state, and local levels, often with overlapping jurisdictions. Each level of government digs its claws into the regulatory morass, and not always for the better, but this preempts nationalization, which would centralize power and control in one level of government. That is not the American way.

A tradition of strong state-level regulation was built up during the mid- to late 19th century, when the federal government did not have the resources, the reach, or the scope to do much nationalizing. America developed some very large national commercial enterprises, such as the railroads, Bell (a phone company), and Western Union (a communications and wire service), which were quite large and far-ranging before the federal government itself had reached a mature size. At that time local government accounted for about half of all government spending in the country and the federal government had few powers of regulation. It wasn’t quite laissez-faire, but America could not rely on its federal government and this shaped the later evolution of the country. To handle these booming corporate entities, America created more state-level regulation of business than was typical for the other industrializing Western countries. That steered Americans away from nationalization as a means for distributing political benefits or disciplining corporations[1]

This policy decision to rely so much on multiple levels of federalistic regulation comes with a price. American failures in physical infrastructure have been the other side of the coin of American successes in business. A strong rule of law, combined with so many legal checks and balances and blocking points, has carved out a protected space for private American businesses. They can operate with relatively secure property rights. At the same time, those same laws and blocking points make it hard to get a lot of things built when a change in property rights is required, whether government or business or both are doing the building. The law is used to obstruct growth and change, and for NIMBYism — “Not In My Backward,” and more generally for giving any litigation-ready interest group a voice in any decision it cares about. Can you imagine a sentence like this being written about China?: “The [New York and New Jersey] Port Authority sent out letters inviting tribe representatives to join the environmental review project, inviting the Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma and the Sand Hills Nation of Nebraska.”[2]

In America background patriotism sustains a rule by general national consensus, and so the American government doesn’t need extensive state-owned companies to build or maintain political support through the creation of so many privileged insiders. The American paradox is this: the reliance on the law reflects a relatively strong and legitimate government, but the multiplication of that law renders government ineffective in a lot of practical matters, especially when it comes to the proverbial “getting things done,” a dimension where the Chinese government has been especially strong.

You should note that although the United States has not so many state-owned enterprises, the American government still has ways of expressing its will on business, or as the case may be, favoring one set of businesses over another. In these latter cases it can be said that American business is expressing its will over government through forms of crony capitalism, a concept which is spreading in both America and China.

The United States has evolved a subtle brand of corporatism and industrial policy that is mostly decentralized and also – this is an important point — relatively stable across shifts of political power. America uses its large country privileges to maintain access to world markets and to protect the property rights of its investors, usually without much regard for whether they are Democrats or Republicans. For instance the State Department works hard to maintain open world markets for films and other cultural goods and services. Toward this end America has used trade negotiations, diplomatic leverage, foreign aid, and also explicit arm-twisting, based on its military commitments to protect allied nations in Western Europe and East Asia. America already had successful entertainment producers, it just wanted to make sure they could earn more money abroad, and that is why the American government usually insists on open access for audiovisual products when it negotiates free trade treaties. Yet in these deals there is not much if any explicit favoritism for one movie or television studio over another, or for one political alliance over another. Democrats are disproportionately overrepresented in Hollywood, but Republican administrations protect the interests of the American entertainment sector nonetheless. It’s about the money and the jobs, not about shifting political coalitions. You’ll note that the independence from particular political coalitions gives the American business environment a particular stability and predictability, to its advantage internationally and otherwise.

[1] See Millward (2013, chapter nine, and p.222 on chartering powers).

[2] That is from Howard (2014, p.10).

Contemporary TC again: Let us hope that I was at least partially correct…

Cass Sunstein on classical liberalism

Here’s what I want to emphasize. I like Hayek a lot less ambivalently than I once did, and von Mises, who once seemed to me a crude and irascible precursor of Hayek, now seems to me to be (mostly) a shining star (and sometimes fun, not least because of his crudeness and irascibility). The reason is simple: They were apostles of freedom. They believed in freedom from fear.

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, I did not see that clearly enough, because they seemed to me to be writing against a background that was sharp and visible to them, but that seemed murky and not so relevant to me — the background set by the 1930s and 1940s, for which Hitler and Stalin were defining. (After all, Hayek helped found the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947.)

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, socialist planning certainly did not seem like a good idea, not at all, but liberalism, as I saw it, had other and newer fish to fry. People like Rawls, Charles Larmore, Edna Ullmann-Margalit (in The Emergence of Norms), Jurgen Habermas (a past and present hero), Amartya Sen (also a past and present hero), Jon Elster (in Sour Grapes and Ulysses and the Sirens), and Susan Okin seemed (to me) to point the way.

I liked their forms of liberalism. Hayek and the Mont Pelerins (and Posner and Epstein) seemed to be fighting old battles, and in important ways to be wrong. With respect to authoritarianism and tyranny, and the power of the state, of course they were right; but still, those battles seemed old.

But those battles never were old. In important ways, Hayek and the Mont Pelerins (and Posner and Epstein, and Becker and Stigler) were right. Liberalism is a big tent. It’s much more than good to see them under it. It’s an honor to be there with them.

Here is the whole Substack, recommended. I am very much in accord with his sentiments here, running in both directions, namely both classical and “more modern” liberalism.