Category: Medicine

When are mental health interventions counterproductive?

The researchers point to unexpected results in trials of school-based mental health interventions in the United Kingdom and Australia: Students who underwent training in the basics of mindfulness, cognitive behavioral therapy and dialectical behavior therapy did not emerge healthier than peers who did not participate, and some were worse off, at least for a while.

And new research from the United States shows that among young people, “self-labeling” as having depression or anxiety is associated with poor coping skills, like avoidance or rumination.

In a paper published last year, two research psychologists at the University of Oxford, Lucy Foulkes and Jack Andrews, coined the term “prevalence inflation” — driven by the reporting of mild or transient symptoms as mental health disorders — and suggested that awareness campaigns were contributing to it.

“It’s creating this message that teenagers are vulnerable, they’re likely to have problems, and the solution is to outsource them to a professional,” said Dr. Foulkes, a Prudence Trust Research Fellow in Oxford’s department of experimental psychology, who has written two books on mental health and adolescence.

Here is more from Ellen Barry at the NYT.

Mask Mandate Costs

There is now an NBER working paper on this topic:

This paper presents the results from a hypothetical set of questions related to mask-wearing behavior and opinions that were asked of a nationally representative sample of over 4,000 participants in early 2022. Mask mandates were hotly debated in public discourse, and though much research exists on benefits of masks, there has been no research thus far on the distribution of perceived costs of compliance. As is common in economic research that aims to assess the value to society of non-market activities, we use survey valuation methods and ask how much participants would be willing to pay to be exempted from rules of mandatory community masking. The survey asks specifically about a 3 month exemption. We find that the majority of respondents (56%) are not willing to pay to be exempted from mandatory masking. However, the average person was willing to pay $525, and a small segment of the population (0.9%) stated they were willing to pay over $5,000 to be exempted from the mandate. Younger respondents stated higher willingness to pay to avoid the mandate than older respondents. Combining our results with standard measures of the value of a statistical life, we estimate that a 3 month masking order was perceived as cost effective through willingness-to-pay questions only if at least 13,333 lives were saved by the policy.

That is by Patrick Carlin, Shyam Raman, Kosali I. Simon, Ryan Sullivan, and Coady Wing. A few comments:

1. Willingness to be paid magnitudes are often much higher than willingness to pay numbers. Especially when issues of justice and desert are involved. I know some people who might say: “I have a right to refuse a mask. I’m not going to pay anything not to wear one, but you would have to pay me a million dollars to put it on.” There are less extreme versions of this view, noting that even in quite normal laboratory circumstances WTBP can be 5x higher than WTP.

2. For many people the value of masking — either positively or negatively — depends on what others do. Some might feel “I guess I can wear a mask, but if you make everyone do that, that is a gross Orwellian dystopia.” Others, perhaps leaning more to the political left, might say: “I am willing to do my share, but of course I expect the same from everyone else. Let us sing this collective song and with our masks dance to the heavens!”

3. Why not just look at what private sector establishments chose when the force of law was not present? Don’t they have the best sense of how to internalize all the different factors behind what their customers want? Of course the answer here will vary, depending on what stage of the pandemic we are in.

Culture splat (a few broad spoilers)

Challengers is a good and original movie. Imagine a 2024 rom com, except the behavior and conventions actually are taken from 2024, and with no apologies. The woman says the word “****ing” a lot, and no one treats this as inappropriate or unusual. There is bisexuality and poly. Society is feminized. Of course opinions will differ on these cultural issues, but the movie is made with conviction and so it is truly a tale of modern romance. Who in the movie is in fact the emptiest shell? Opinions will differ.

Zendaya dominates the screen — for how long has it been since we have had an actress this central and this charismatic?

Also, I quite like the new Beyonce album, and Metaculus estimates the chance of an H5N1 pandemic at about two percent.

What should I ask Paul Bloom?

Yes I will be doing a Conversation with him. Here is Wikipedia:

Paul Bloom…is a Canadian American psychologist. He is the Brooks and Suzanne Ragen Professor Emeritus of psychology and cognitive science at Yale University and Professor of Psychology at the University of Toronto. His research explores how children and adults understand the physical and social world, with special focus on language, morality, religion, and art.

Here is Paul’s own home page. Here are Paul’s books on Amazon. Here is Paul on Twitter. Here is Paul’s new Substack. Here is Paul’s post on how to be a good podcast guest.

Tying the Knot

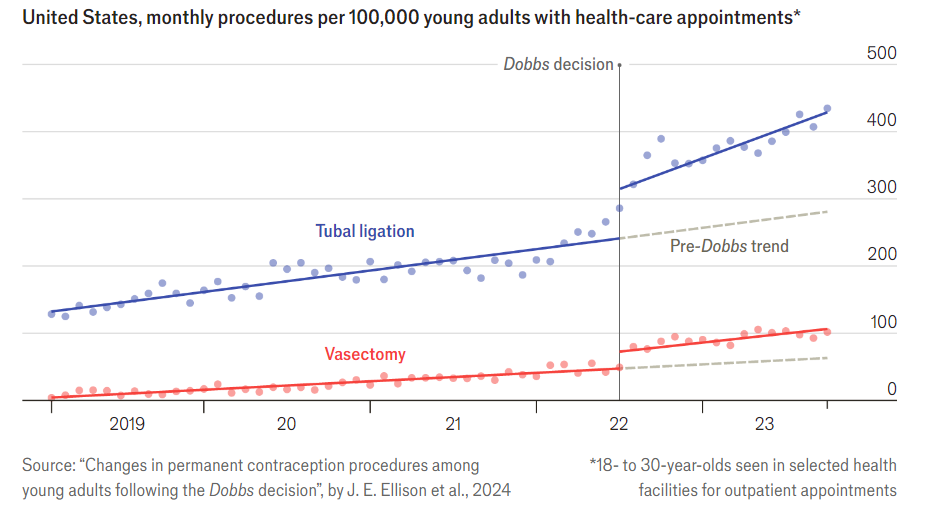

Dobbs, of course, was the Supreme Court decision saying that the constitution does not provide a right to abortion, thus leading to restrictions on abortion in many states. The pictures is from The Economist, the original paper is here.

Guinea pig questions

If someone demographically normal and not especially at-risk wants to serve as a guinea pig, what is the optimal allocation of that resource?

Is there any formal discussion of this question? I know they say “there is always an Effective Altruism blog post,” but is there?

Mostly I have medicine and medical experimentation in mind, but I can imagine other answers as well, such as “trying to leap forty flaming cars with a motorcycle.” Though I doubt that one will end up as the winner. In any case, I am assuming away legal constraints. Where can you volunteer as a guinea pig for the highest social value?

The Adderall Shortage: DEA versus FDA in a Regulatory War

A record number of drugs are in shortage across the United States. In any particular case, it’s difficult to trace out the exact causes of the shortage but health care is the US’s most highly regulated, socialist industry and shortages are endemic under socialism so the pattern fits. The shortage of Adderall and other ADHD medications is a case in point. Adderall is a Schedule II controlled substance which means that in addition to the FDA and other health agencies the production of Adderall is also regulated, monitored and controlled by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

The DEA aims to “combat criminal drug networks that bring harm, violence, overdoses, and poisonings to the United States.” Its homepage displays stories of record drug seizures, pictures of “most wanted” criminal fugitives, and heroic armed agents conducting drug raids. With this culture, do you think the DEA is the right agency to ensure that Americans are also well supplied with legally prescribed amphetamines?

The DEA aims to “combat criminal drug networks that bring harm, violence, overdoses, and poisonings to the United States.” Its homepage displays stories of record drug seizures, pictures of “most wanted” criminal fugitives, and heroic armed agents conducting drug raids. With this culture, do you think the DEA is the right agency to ensure that Americans are also well supplied with legally prescribed amphetamines?

Indeed, there is a large factory in the United States capable of producing 600 million doses of Adderall annually that has been shut down by the DEA for over a year because of trivial paperwork violations. The New York Magazine article on the DEA created shortage has to be read to be believed.

Inside Ascent’s 320,000-square-foot factory in Central Islip, a labyrinth of sterile white hallways connects 105 manufacturing rooms, some of them containing large, intricate machines capable of producing 400,000 tablets per hour. In one of these rooms, Ascent’s founder and CEO — Sudhakar Vidiyala, Meghana’s father — points to a hulking unit that he says is worth $1.5 million. It’s used to produce time-release Concerta tablets with three colored layers, each dispensing the drug’s active ingredient at a different point in the tablet’s journey through the body. “About 25 percent of the generic market would pass through this machine,” he says. “But we didn’t make a single pill in 2023.”

… the company has acknowledged that it committed infractions. For example, orders struck from 222s must be crossed out with a line and the word cancel written next to them. Investigators found two instances in which Ascent employees had drawn the line but failed to write the word.

The causes of the DEA’s crackdown appears to be precisely the contradiction in its dueling missions. Ascent also produces opioids and the DEA crackdown was part of what it calls Operation Bottleneck, a series of raids on a variety of companies to demand that they account for every pill produced.

The causes of the DEA’s crackdown appears to be precisely the contradiction in its dueling missions. Ascent also produces opioids and the DEA crackdown was part of what it calls Operation Bottleneck, a series of raids on a variety of companies to demand that they account for every pill produced.

To be sure, the opioid epidemic is a problem but the big, multi-national plants are not responsible for fentanyl on the streets and even in the early years the opioid epidemic was a prescription problem (with some theft from pharmacies) not a factory theft problem (see figure at left). Maybe you think Adderall is overprescribed. Could be but the DEA is supposed to be enforcing laws not making drug policy. The one thing one can say for certain is that Operation Bottleneck has surely been a success in creating shortages of Adderall.

The DEA’s contradictory role in both combating the illegal drug trade and regulating the supply of legal, prescription drugs is highlighted by the fact that at the same as the DEA was raiding and shutting down Ascent, the FDA was pleading with them to increase production!

For Ascent, one of the more frustrating parts of being told by the government to stop making Adderall is that other parts of the government have pleaded with the company to make more. The company says that on multiple occasions, officials from the FDA asked it to increase production in response to the shortage, and that Ron Wyden, the Democratic senator from Oregon, also pressed Ascent for help. They received responses similar to those the company gave the stressed-out callers looking for pills: Ascent didn’t have any information. Instead, the company directed them to the DEA.

UNOS Kills

I’ve long been an advocate of increasing the use of incentives in organ procurement for transplant; either with financial incentives or with rules such as no-give, no-take which prioritize former potential organ donors on the organ recipient list. What I and many reformers failed to realize, however, is that the current monopolized system is so corrupt, poorly run and wasteful that thousands of lives could be saved even without incentive reform. (To be clear, these issues are related since an incentivized system would never have become so monopolized and corrupt in the first place but that is a meta-issue for another day.) Here, for example, is one incredible fact:

An astounding one out of every four kidneys that’s recovered from a generous American organ donor is thrown in the trash.

Here’s another:

Organs are literally lost and damaged in transit every single week. The OPTN contractor is 15 times more likely to lose or damage an organ in transit than an airline is a suitcase.

Organs are not GPS-tracked!

In an era when consumers can precisely monitor a FedEx package or a DoorDash dinner delivery, there are no requirements to track shipments of organs in real time — or to assess how many may be damaged or lost in transit.

“If Amazon can figure out when your paper towels and your dog food is going to arrive within 20 to 30 minutes, it certainly should be reasonable that we ought to track lifesaving organs, which are in chronic shortage,” Axelrod said.

Here’s one more astounding statistics:

Seventeen percent of kidneys are offered to at least one deceased person before they are transplanted….

Did you get that? The tracking system for patients is so dysfunctional that 17% of kidneys are offered to patients who are already dead–thus creating delays and missed opportunities.

All of this was especially brought to light by Organize, a non-profit patient advocacy group who under an innovative program embedded with the HHS and working with HHS staff produced hard data.

Many more details are provided in this excellent interview with Greg Segal and Jennifer Erickson, two of the involved principals, in the IFPs vital Substack Statecraft.

Another Thursday link

Scott Alexander rules against Lab Leak as most likely. Of course this is not the final word, but it is fair to say that Lab Leak is not the go-to hypothesis here. Analytical throughout. And Nabeel comments.

Sentences of note

COVID-19 vaccination reduced the risk of post-COVID-19 cardiac and thromboembolic outcomes. These effects were more pronounced for acute COVID-19 outcomes, consistent with known reductions in disease severity following breakthrough versus unvaccinated SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Here is the full article by Núria Mercadé-Besora, et.al.

In Conversation with Próspera CEO Erick Brimen & Vitalia Co-Founder Niklas Anzinger

During my visit to Prospera, one of Honduras’ private governments under the ZEDE law, I interviewed Prospera CEO Erick Brimen and Vitalia co-founder Niklas Anzinger. I learned a lot in the interview including the real history of the ZEDE movement (e.g. it didn’t begin with Paul Romer). I also had not fully appreciated the power of reciprocity stacking.

Companies in Prospera have the unique option to select their regulatory framework from any OECD country, among others. Erick Brimen elaborated in the podcast how this enables companies to do normal, OECD approved, things in Prospera which literally could not be done legally anywhere else in the world.

…so in the medical world for instance you have drugs that are approved in some countries but not others and you have medical practitioners that are licensed in some countries but not the others and you have medical devices approved in some countries but not others and there’s like a mismatch of things that are approved in OECD countries but there’s no one location where you can say hey if they’re approved in any country they’re approved here. That is what Prosper is….Our hypothesis is that just by doing that we can leapfrog to a certain extent and it’s got nothing to do with the wild west or doing weird things.

…so here so you can have a drug approved in the UK but not in the US with a doctor licensed in the US but not in the UK with a medical device created in Israel but not yet approved by the FDA following a procedure that has been say innovated in Canada, all of that coming together here in Prospera.

As it should be

The next time you send your doctor an email, don’t be surprised if they charge you a fee to answer.

More healthcare groups are charging fees to answer patients’ electronic messages, often the ones you exchange via their portal. Doctors say it’s only fair if they’re spending time on the messages and note that an email discussion can often save you the time of having to come in.

The typical cost of an email message claim was $39 in 2021, including both the portion paid by insurance and by the patient, according to a Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker analysis.

Some patients have been taken aback by the charges. They are surprised at the notifications on portals about the change, and irritated at the idea of a new fee.

Dr. Lauren Oshman, a family physician and associate professor at the University of Michigan Medical School, says she initially experienced some patient resistance and anger about the prospect of being billed for emails.

Now, she says, patients are typically pleased that they are able to get a direct response from her through a portal message.

“They’re thrilled when they get me directly,” she says.

Here is more from the WSJ, via the excellent Daniel Lippman.

What can be learned from Singaporean health care institutions?

Besides the usual, that is. Max Thilo of the UK has a new and excellent study on this, here is one excerpt from the foreword by Lord Warner:

Second, and critical, the Singaporeans are not fixated on delivering services from acute hospitals – the most expensive part of any healthcare system because of its fixed overheads and expensive maintenance. As this report demonstrates “the reason why Singapore spends so much less on health than other developed countries is its low hospital utilisation.” Instead, Singapore has invested in highly productive polyclinics and low-cost telemedicine. The result is that Singaporeans can visit their GP more often than English patients. In their polyclinics they also improve productivity by separating chronic and acute care.

And from Max:

During a recent trip, I met with the CEO of the largest telemedicine provider in Singapore. He casually mentioned that UK patients were already using his service. This seemed surprising. No comprehensive data is available for the costs of UK telemedicine services, so I googled the cost of online appointments in the UK and Singapore. Singaporean appointments are less than half the price of those in the UK. The most affordable online appointment I found in the UK was £29. Yet, many providers charge significantly more – for instance, Babylon Health lists its price for private GP appointments at £59. In contrast, Doctor Anywhere, Singapore’s leading telemedicine provider, offers services for just £12.27 Doctor Anywhere has an app where patients can log on and see patients virtually. They make and then register the diagnosis. The rest of the process, including referrals and prescriptions, is automated.

Recommended.

U.S.A. yikes fact of the day

Between January 2016 and December 2022, the monthly antidepressant dispensing rate increased 66.3%, from 2575.9 to 4284.8. Before March 2020, this rate increased by 17.0 per month (95% confidence interval: 15.2 to 18.8). The COVID-19 outbreak was not associated with a level change but was associated with a slope increase of 10.8 per month (95% confidence interval: 4.9 to 16.7). The monthly antidepressant dispensing rate increased 63.5% faster from March 2020 onwards compared with beforehand. In subgroup analyses, this rate increased 129.6% and 56.5% faster from March 2020 onwards compared with beforehand among females aged 12 to 17 years and 18 to 25 years, respectively. In contrast, the outbreak was associated with a level decrease among males aged 12 to 17 years and was not associated with a level or slope change among males aged 18 to 25 years.

That is by Kao-Ping Chua, et.al., from the high-quality journal Pediatrics. So that is how we respond to crises? By doping up the young women? Yikes!

Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

It’s happening

Is DNA all you need?

In new work, we report Evo, a genomic foundation model that learns across the fundamental languages of biology: DNA, RNA, and proteins. Evo is capable of both prediction tasks and generative design, from molecular to whole genome scale. pic.twitter.com/BPo9ggHhmp

— Patrick Hsu (@pdhsu) February 27, 2024