Category: Medicine

Dose Optimization Trials Enable Fractional Dosing of Scarce Drugs

During the pandemic, when vaccines doses were scarce, I argued for fractional dosing to speed vaccination and maximize social benefits. But what dose? In my latest paper, just published in PNAS, with Phillip Boonstra and Garth Strohbehn, I look at optimal trial design when you want to quickly discover a fractional dose with good properties while not endangering patients in the trial.

[D]ose fractionation, rations the amount of a divisible scarce resource that is allocated to each individual recipient [3–6]. Fractionation is a utilitarian attempt to produce “the greatest good for the greatest number” by increasing the number of recipients who can gain access to a scarce resource by reducing the amount that each person receives, acknowledging that individuals who receive lower doses may be worse off than they would be had they received the “full” dose. If, for example, an effective intervention is so scarce that the vast majority of the population lacks access, then halving the dose in order to double the number of treated individuals can be socially valuable, provided the effectiveness of the treatment falls by less than half. For variable motivations, vaccine dose fractionation has previously been explored in diverse contexts, including Yellow Fever, tuberculosis, influenza, and, most recently, monkeypox [7–12]. Modeling studies strongly suggest that vaccine dose fractionation strategies, had they been implemented, would have meaningfully reduced COVID-19 infections and deaths [13], and perhaps limited the emergence of downstream SARS-CoV-2 variants [6].

…Confident employment of fractionation requires knowledge of a drug’s dose-response relationship [6, 13], but direct observation of both that relationship and MDSE, rather than pharmacokinetic modeling, appears necessary for regulatory and public health authorities to adopt fractionation [15, 16]. Oftentimes, however, early-phase trials of a drug develop only coarse and limited dose-response information, either intentionally or unintentionally. A speed-focused approach to drug development, which is common for at least two reasons, tends to preclude dose-response studies. The first reason is a strong financial incentive to be “first to market.” The majority of marketed cancer drugs, for example, have never been subjected to randomized, dose-ranging studies [17, 18]. The absence of dose optimization may raise patients’ risk. Further, in an industry sponsored study, there is a clear incentive to test the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) in order to observe a treatment effect, if one exists. The second reason, observed during the COVID-19 pandemic, is a focus on speed for public health. Due to ethical and logistical challenges, previously developed methods to estimate dose-response and MDSE have not routinely been pursued during COVID-19 [19]. The primary motivation of COVID-19 clinical trial infrastructure has been to identify any drug with any efficacy rather than maximize the benefits that can be generated from each individual drug [3, 18, 20, 21]. Conditional upon a therapy already having demonstrated efficacy, there is limited desire on the part of firms, funders, or participants to possibly be exposed to suboptimal dosages of an efficacious drug, even if the lower dose meaningfully reduced risk or extended benefits [16]. Taken together, then, post-marketing dose optimization is a commonly encountered, high-stakes problem–the best approach for which is unknown.

…With that motivation, we present in this manuscript the development an efficient trial design and treatment arm allocation strategy that quickly de-escalates the dose of a drug that is known to be efficacious to a dose that more efficiently expands societal benefits.

The basic idea is to begin near the known efficacious dose level and then deescalate dose levels but what is the best de-escalation strategy given that we want to quickly find an optimal dosage level but also don’t want to go so low that we endanger patients? Based on Bayesian trials under a variety of plausible conditions we conclude that the best strategy is Targeted Randomization (TR). At each stage, TR identifies the dose-level most likely to be optimal but randomizes the next subject(s) to either it or one of the two dose-levels immediately below it. The probability of randomization across three dose-levels explored in TR is proportional to the posterior probability that each is optimal. This strategy balances speed of optimization while reducing danger to patients.

Read the whole thing.

The Role of Friends in the Opioid Epidemic

Your friends are not always good for you:

The role of friends in the US opioid epidemic is examined. Using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (Add Health), adults aged 25-34 and their high school best friends are focused on. An instrumental variable technique is employed to estimate peer effects in opioid misuse. Severe injuries in the previous year are used as an instrument for opioid misuse in order to estimate the causal impact of someone misusing opioids on the probability that their best friends also misuse. The estimated peer effects are significant: Having a best friend with a reported serious injury in the previous year increases the probability of own opioid misuse by around 7 percentage points in a population where 17 percent ever misuses opioids. The effect is driven by individuals without a college degree and those who live in the same county as their best friends.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Effrosyni Adamopoulou, Jeremy Greenwood, Nezih Guner, and Karen Kopecky.

The economics of semaglutide

…while one would certainly like to have these drugs available to these patients, if the price of these drugs doesn’t come down, you can make a good argument their cost will literally break Medicare. Why? Well, roughly 35% of Medicare patients are overweight or obese. Roughly 75% of people over 65 have coronary artery disease. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6616540/#:~:text=The%20American%20Heart%20Association%20(AHA,age%20of%2080%20%5B3%5D.)

Even if you assume these numbers are independent of each other, which is very unlikely, because overweight people are more likely to have cardiovascular disease, this means at least 26% of the roughly 31 million Medicare recipients (and likely more) might benefit from these drugs. We have an eligible population for these drugs therefore of more than 8 million people. At current list prices we would be spending 8mil*1350*12 or about 130 billion dollars a year. Total Medicare spending is about 725 billion a year. So, Medicare spending would go up by more than 17% overnight and stay at that level for a long time to come.

Here is more from Gary Cornell, mostly about the degree of effectiveness.

Interview with Weight Loss Drugs Inventor Lotte Bjerre Knudsen

Knudsen: I don’t care that much about money, I’m a socialist! Here in Scandinavia, we teach our children teamwork from an early age. It’s not about the individual. And that’s how I am too. I have never asked for a raise in 34 years.

DER SPIEGEL: You never got more money? Not even now?

Knudsen: Yes, of course. But I didn’t push. I can’t see that capitalism and money make people happy. At Novo Nordisk, I have always preferred to use my credibility to demand more funding for science, not more salary for myself. I also have no intellectual property rights. They belong to the company because I gave them up when I was employed.

Here is the full interview, interesting throughout. Via the ever-excellent The Browser.

Asimov Press

Asimov Press, a new publishing venture that will produce books + magazines about progress in biotechnology, launched today. We’ll publish new articles regularly and hope you’ll follow! Modelled on Stripe Press, and we’re advised by a Works in Progress co-founder.

More on Pharma Pricing

A reader in the industry writes with excellent comments on yesterday’s post on the Chris Rock hypothesis.

Long-time reader, first-time emailer–love the show ;). I’ve been in and around the pharma industry for nearly 30 years, and I’ve spent time in gene therapy/gene editing where the one-time cure model dominates. Some thoughts on chronic vs. curative dosing and why a curative therapy is likely worth less:

- There’s a potential mismatch between payment for a drug and the accrual of value that justifies its price point. If I take a curative therapy for a disease like hemophilia (e.g., the new $2.9 M drug, Roctavian), the insurance company immediately incurs the cost of the drug, but the prime financial benefits (no more expensive chronic therapy, reduced expensive visits to the hospital) accrue over time. Patients switch insurance companies as they switch jobs, so the “payout” that justifies the treatment price accrues to the subsequent insurers. On chronic therapy, if a patient switches to another insurer, the new insurer picks up the payments so there’s no such disconnect. Rationally, insurers should pay more for chronic therapy, even in present value terms.

- Durability of effect is unknown until it isn’t. It’s difficult to charge for a drug as a cure until such time you know it’s a cure and have proven it as such. How long do you have to follow treated patients to prove that? Gene therapies are starting to show waning efficacy in some cases. The FDA mandates that you cannot include something in the drug label that has not been proven. Payors will point to a label and ask why they should pay for something that’s not on there. This can be mitigated by programs where the drug company pays back a portion of the cost if it doesn’t work, but collecting on that seems like a huge hassle–how do you prove that it stopped working (I can hear Mike Munger–“the answer to your question is transaction costs…”)?

- Sticker shock and headline numbers. A drug that costs $3 M or more is something the White House can use at a podium and get a reaction. Never mind that it gets paid back pretty quickly by discontinuing a therapy that costs hundreds of thousands per year–life-saving drugs should not cost millions of dollars! This puts downward pressure on one-time cures.

So, my perspective is that it is more difficult for a one-time treatment/cure to capture the value it creates vs. a chronic therapy. So, why did Lilly shares tumble on the news? More important than duration of therapy is market share vs. competitors. A more permanent solution (with no rebound after discontinuation) would more than make up for lost revenue on the back end by taking share from the competition on the front end. And THAT is why pharma is incentivized to pursue cures. Making a better drug will beat the competition, and a cure is a better drug. Big Pharma doesn’t necessarily pursue curative treatments directly because they don’t know how. Technologies like CRISPR and mRNA have to come up via biotechs that are purpose-built to maximize the platforms’ value and to understand/navigate the underlying technology. That said, Big Pharma has inked HUGE deals to gain access to these technologies (e.g., Pfizer/BioNTech), so they do seem to come around eventually.

These are all excellent points. On point 1, note that Medicaid creates similar incentives in that insurance firms want to farm long term costs onto Medicaid.

Point 3 suggests that we should be especially wary of price controls on cures. Sticker shock may drive us to price controls leaving us with treatments that look cheaper but are even more expensive in the long-run (and by present discounted value). Sovaldi is a case in point. Its initial $84,000 price generated huge opposition even though it typically cured hepatitis C infections and avoided many later liver cancers and saved money overall. Indeed, as I pointed out earlier, Sovaldi so reduced the number of liver transplants that more people with other diseases ended up with life-saving transplants.

This is also what I meant by starting in the right place. If you start in the right place you have some hope of getting to real causes and possible solutions.

A Weighty Puzzle-Answers

Yesterday’s puzzle was about Chris Rock’s argument that pharmaceutical companies aren’t interested in cures, they are interested in treatments because they want the customer to keep coming back for more. The argument is common. So common that both ChatGPT and Claude completely botch this question. Claude, for example, says:

…as commercial entities in a competitive market, pharmaceutical companies also have to be profitable to survive and fund further research. In that sense, financially, an ongoing need to buy a treatment provides more direct revenue than a one-time cure.

Sigh. Claude is not nearly as funny as Chris Rock but without Rock’s delivery and worldly cynicism is the error now obvious?

Consider two lightbulbs, one lasts for 2 years the other lasts for 1 year. Which lightbulb is more profitable to sell? Any sensible analysis must begin with the following simple point: A lightbulb that lasts for 2 years is worth about twice as much as a lightbulb that lasts one year. Thus, assuming for the moment that costs of production are negligible, there is no secret profit to be had from selling two 1-year lightbulbs compared to selling one 2-year lightbulb. The firm that sells 1-year lightbulbs hasn’t hit on a secret profit-sauce because its customers must come back for more. If it did it could sell really profitable 1-month bulbs!

The same thing is true for pharmaceuticals. A treatment that lasts for 10 years is worth about ten times as much as an annual treatment. Or, to put it the other way, a treatment that lasts for 10 years is worth about the same as 10 annual treatments producing the same result. (n.b. yes, discounting, but discounting by both consumers and firms means that nothing fundamental changes.)

The simple argument starts us in the right place. We can then add arguments, on both sides, depending on context. In the case of Eli Lilly and Zepbound I think the major argument to add is that investors were likely pricing in a small chance that Zepbound had longer-lasting effects than Wegovy and when this was shown not to be true the price of the stock dropped. Thus, investors were pricing in some chance that Zepbound could have had greater market power–Sure made this argument in the comments yesterday.

Another argument: Consumers might be rationally or irrationally myopic. A rational myopia, for example, might be brought about if consumers don’t believe claims of longer durability. Quite possible. Econ question number 2–other than waiting ten years how could a firm convince buyers that its product was more durable than that of its competitors? (Hint: 🦚. Or you can find the answer is in Modern Principles.). Econ question number 3–if consumers were irrationally myopic would firms sell the treatment or, sell the cure with a different pricing strategy?

The cost of producing durability also matters–a lot. Sometimes cures are cheaper (one pill is cheaper than 10) but sometimes cures are more expensive. If longer durability is more expensive, there will be a tradeoff–these lightbulbs are more expensive but I will have to replace them less often–and the market process will work things out, perhaps differently for different consumers.

There are also subtle issues with price discrimination (see here but also here for some ideas) and Coase’s durable good monopoly argument (which I think is completely wrong in this context) as well as other issues but there is little point discussing the subtleties if we don’t get the big issues right.

The big issue to get right is that renting isn’t inherently more profitable than selling.

Addendum: When I pointed Claude to the above arguments, Claude responded “You make an excellent observation…there are good reasons why a one-time cure could potentially warrant an exceptionally high price point, well above an annual treatment cost. The pricing strategies pharmaceutical firms employ would analyze all these aspects in depth. Thank you for pushing me to recognize my flawed assumptions. I appreciate the opportunity to clarify my understanding here. Let me know if you have any other insightful points!”

I wonder if the commentators will be so wise and gracious?

A Weighty Economics Puzzle

Yesterday a new study was released showing that patients on Eli Lilly’s Zepbound (tirzepatide) lost weight but regained a meaningful percentage after being switched to placebo. Eli Lilly stock “tumbled” on the news, e.g. here and here or see below. In other words, Eli Lilly stock fell when investors learned that to keep the weight off patients would have to continue to take Zepbound for life. Hmmm…that certainly violates what the man in the street thinks about pharmaceutical companies and profits. Chris Rock, for example, says the money isn’t in the cure, the money’s in the comeback. If so, shouldn’t this have been great news for Eli Lilly?

So why did Eli Lilly stock fall? Could it be that the Chris Rock and the man in the street are wrong? I will leave this as an exercise for the reader.

No Child Left Behind: Accelerate Malaria Vaccine Distribution!

My post What is an Emergency? The Case for Rapid Malaria Vaccination, galvanized the great team at 1DaySooner. Here is Zacharia Kafuko writing at Foreign Policy:

Right now, enough material to make 20 million doses of a lifesaving malaria vaccine is sitting on a shelf in India, expected to go unused until mid-2024. Extrapolating from estimates by researchers at Imperial College London, these doses—enough for 5 million children—could save more than 31,000 lives, at a cost of a little more than $3,000 per life. But current plans by the World Health Organization to distribute the vaccine are unclear and have been criticized as lacking urgency.

…Vaccine deployment and licensure is an incredibly complex scientific, legal, and logistical process involving numerous parties across international borders. Roughly speaking, after the WHO recommends vaccines (such as R21), it must also undertake a prequalification process and receive recommendations from its Strategic Advisory Group of Experts before UNICEF is allowed to purchase vaccines. Then Gavi—a public-private global health alliance—can facilitate delivery by national governments, which must propose their anticipated demand to Gavi and make plans to distribute the vaccines.

Prequalification can take as long as 270 days after approval. However, the COVID-19 vaccines were rolled out within weeks of WHO’s approval, using the separate EUL process rather than the more standard prequalification process that R21 is now undergoing.

For COVID-19 vaccines, EUL was available because the pandemic was undeniably an emergency. Given the staggering scale of deaths of children in sub-Saharan Africa every year, shouldn’t we also be treating malaria vaccine deployment as an emergency?

The R21 malaria vaccine does not legally qualify for EUL because malaria already has a preventive and curative toolkit available. My concern is that this normalizes the deaths of hundreds of thousands of children each year in Africa.

We can move more quickly and save more lives, if we have the will.

Don’t Let the FDA Regulate Lab Tests!

I have been warning about the FDA’s power grab over lab developed tests. Lab developed tests have never been FDA regulated except briefly during the pandemic emergency when such regulation led to catastrophic consequences. Catastrophic consequences that had been predicted in advanced by Paul Clement and Lawrence Tribe. Despite this, for reasons I do not understand, the FDA plan is marching forward but many other people are starting to warn of dire consequences. Here, for example, is the executive summary from a letter by ARUP Laboratories, a non-profit enterprise of the University of Utah Department of Pathology:

ARUP urges the FDA to withdraw the proposed rule:

- The FDA proposal will reduce, an in many cases eliminate, access to safe and essential testing services, particularly for patients with rare diseases.

- Laboratory-developed tests are not devices as defined by the Medical Device Amendments of 1976, nor are clinical laboratories acting as manufacturers.

- The FDA does not have the statutory authority to regulate laboratory-developed tests.

- The FDA does not have the authority to regulate states, or state-owned entities. This is particularly relevant for the proposed rule regarding academic medical centers.

- The FDA’s regulatory impact analysis is flawed in its design, source information, methods. and conclusions, and it systematically overestimates purported benefits of the proposed rule and dramatically underestimates its cost to society, the healthcare industry, and the ability to provide ongoing essential laboratory services to patients.

- The proposed rule would significantly limit the ability of clinical laboratories to respond quickly to future pandemic, chemical, and/or radiologic public health threats.

- The proposed rule would not be easily implementable, and it would create an insurmountable backlog of submissions that would hinder diagnostic innovation.

- The proposed rule limits the practice of laboratory medicine.

- The FDA has not evaluated less restrictive, easily administered alternatives, such as CLIA reform. This is particularly relevant for common test modifications used in most hospital and academic medical center settings.”

Here is the American Hospital Association:

…we strongly believe that the FDA should not apply its device regulations to hospital and health system LDTs. These tests are not devices; rather, they are diagnostic tools developed and used in the context of patient care. As such, regulating them using the device regulatory framework would have an unquestionably negative impact on patients’ access to essential testing. It would also disrupt medical innovation in a field demonstrating tremendous benefits to patients and providers.

Here is Mass General Brigham, a non-profit hospital system, affiliated with Harvard, and the largest hospital-based research enterprise in the United States:

…we are concerned with the heavy regulatory burden of this proposal. In implementing any regulatory structure, policymakers must consider if the benefits outweigh the costs. Given that FDA predicts 50 percent of tests would require premarket review, and 5 percent will require premarket approval, we have serious concerns that the costs may outweigh the benefits. Given that many LDTs are hospital-based and will never be commercialized, hospitals will have little incentive or ability to develop future LDTs under this proposed rule as they will have little to no opportunity to offset the costs associated with these new regulatory requirements. We are concerned that the regulatory burden could have significant implications on responsible innovation especially for LDTs targeting rare conditions, or public health emergencies.

Two U.S. public lab directors personally reached out to me to ask me amplify the warning. Consider it amplified!

Today is the last day for public comment. Get your comments in!

One Reason Why American Health Care is Expensive

tl/dr; Canadian woman is diagnosed with cancer, told she has 2 years to live at most, that she is not a candidate for surgery but would she like medical help committing suicide? She declines, comes to the United States, spends a lot of money, and is treated within weeks. Her health insurance is refusing to pay.

Global News: Ducluzeau said her family doctor told her that with this type of cancer, they usually do a procedure called HIPEC, which involves delivering high doses of chemotherapy into the abdomen to kill the cancer cells. But when she saw the consulting surgeon at the BC Cancer Agency in January, she said she was told she was not a candidate for surgery.

“Chemotherapy is not very effective with this type of cancer,” Ducluzeau said the surgeon told her. “It only works in about 50 per cent of the cases to slow it down. And you have a life span of what looks like to be two months to two years. And I suggest you talk to your family, get your affairs in order, talk to them about your wishes, which was indicating, you know, whether you want to have medically assisted dying or not.”

…Her brother contacted his mother-in-law who lives in Taiwan and she was able to get some advice from an oncologist there, after only waiting an hour. That oncologist confirmed that HIPEC was the treatment for Ducluzeau’s cancer. She set up a Zoom call with that oncologist later that week but then she found out about Dr. Armando Sardi at the Mercy Medical Center in Baltimore, Maryland.

“I had an appointment to speak with him via Zoom as well within a week and then also in Washington State,” she explained. “So there were two hospitals in Taiwan, one in Washington State and one in Baltimore that were able to take me as a patient.”

Ducluzeau decided to get treatment with Sardi in Baltimore.

…“I had to fly to California to get one of my diagnostic scans done there, a PET scan, because I wasn’t getting in here and I had to pay to have another CT scan done when I got to Baltimore because they couldn’t get it in time before I left,” she said.

Before she left, Ducluzeau said she called BC Cancer to ask how long it might be to see the oncologist was told it could be weeks, months, or longer, they had no idea.

“And I said, ‘Well, will it help if my doctor phones on my behalf?’ And they said, ‘no’. And my doctor submitted my referral again and still no word. No word at all from (BC Cancer) until after I flew to Baltimore, had my surgery and got home.”

With the help of a surgeon in Vancouver, Ducluzeau finally got a telephone appointment with an oncologist at BC Cancer for the middle of March – two-and-a-half months after receiving her diagnosis and the news that she may only have two months to two years to live.

…The BC Cancer Agency is refusing to provide documentation that would allow Ducluzeau to be reimbursed for the cost of out-of-country care, citing she did not proceed with additional investigations, such as a colonoscopy and laparoscopy.

“Universal healthcare really doesn’t exist,” Ducluzeau said. “My experience is it’s ‘do it yourself’ health care and GoFundMe health care.

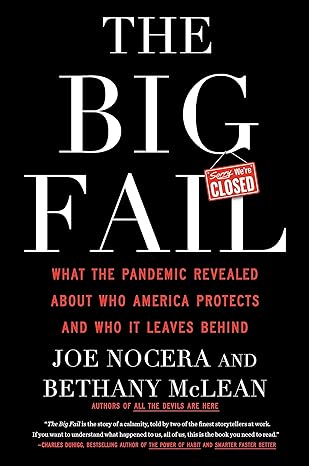

The Big Fail

The Big Fail, Joe Nocera and Bethany McLean’s new book about the pandemic, is an angry book. Rightly so. It decries the way the bien pensant, the self-righteously conventional,  were able to sideline, suppress and belittle other voices as unscientific, fraudulent purveyors of misinformation. The Big Fail gives the other voices their hearing— Martin Kulldorff, Sunetra Gupta, Jay Bhattacharya and Emily Oster are recast not as villains but as heroes; as is Ron DeSantis who is given credit for bucking the conventional during the pandemic (Nocera and McLean wonder what happened to the data-driven DeSantis, as do I.)

were able to sideline, suppress and belittle other voices as unscientific, fraudulent purveyors of misinformation. The Big Fail gives the other voices their hearing— Martin Kulldorff, Sunetra Gupta, Jay Bhattacharya and Emily Oster are recast not as villains but as heroes; as is Ron DeSantis who is given credit for bucking the conventional during the pandemic (Nocera and McLean wonder what happened to the data-driven DeSantis, as do I.)

Amazingly, even as highly-qualified epidemiologists and economists were labelled “anti-science” for not following the party line, the biggest policy of them all, lockdowns, had little to no scientific backing:

…[lockdowns] became the default strategy for most of the rest of the world. Even though they had never been used before to fight a pandemic, even though their effectiveness had never been studied, and even though they were criticized as authoritarian overreach—despite all that, the entire world, with a few notable exceptions, was soon locking down its citizens with varying degrees of severity.

In the United States, lockdowns became equated with “following the science.” It was anything but. Yes, there were computer models suggesting lockdowns would be effective, but there were never any actual scientific studies supporting the strategy. It was a giant experiment, one that would bring devastating social and economic consequences.

The narrative lined up “scientific experts” against “deniers, fauxers, and herders” with the scientific experts united on the pro-lockdown side (the following has no indent but draws from an earlier post). But let’s consider. In Europe one country above all others followed the “ideal” of an expert-led pandemic response. A country where the public health authority was free from interference from politicians. A country where the public had tremendous trust in the state. A country where the public were committed to collective solidarity and public welfare. That country, of course, was Sweden. Yet in Sweden the highly regarded Public Health Agency, led by state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell, an expert in infectious diseases, opposed lockdowns, travel restrictions, and the general use of masks.

It’s important to understand that Tegnell wasn’t an outsider marching to his own drummer, anti-lockdown was probably the dominant expert opinion prior to COVID. In a 2006 review of pandemic policy, for example, four highly-regarded experts argued:

It is difficult to identify circumstances in the past half-century when large-scale quarantine has been effectively used in the control of any disease. The negative consequences of large-scale quarantine are so extreme (forced confinement of sick people with the well; complete restriction of movement of large populations; difficulty in getting critical supplies, medicines, and food to people inside the quarantine zone) that this mitigation measure should be eliminated from serious consideration.

Travel restrictions, such as closing airports and screening travelers at borders, have historically been ineffective.

….a policy calling for communitywide cancellation of public events seems inadvisable.

The authors included Thomas V. Inglesby, the Director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, one of the most highly respected centers for infectious diseases in the world, and D.A. Henderson, the legendary epidemiologist widely credited with eliminating smallpox from the planet.

Nocera and McLean also remind us of the insanity of the mask debate, especially in the later years of the pandemic.

But by the spring of 2022, the CDC had dropped its mask recommendations–except, incredibly, for children five and under, who again, were the least likely to be infected.

…Once again it was Brown University economist Emily Oster who pointed out how foolish this policy was…The headline was blunt: Masking Policy is Incredibly Irrational Right Now. In this article she noted that even as the CDC had dropped its indoor mask requirements for kids six and older, it continued to maintain the policy for younger children. “Some parents of young kids have been driven insane by this policy,” Oster wrote, “I sympathize–because the policy is completely insane…”

As usual, her critics jumped all over her. As usual, she was right.

Naturally, I don’t agree with everything in the Big Fail. Nocera and McLean, for example, are very negative on the role of private equity in hospitals and nursing homes. My view is that any theory of what is wrong with American health care is true because American health care is wrong in every possible way. Still, I don’t see private equity as a driving force. It’s easy to find examples where private equity owned nursing homes performed poorly but so did many other nursing homes. More systematic analyses find that PE owned nursing homes performed about the same, worse or better than other nursing homes. Personally, I’d bet on about the same overall. Covid in the Nursing Homes: The US Experience (open), my paper with Markus Bjoerkheim, shows that what mattered more than anything else was simply community spread (see also this paper for the ways in which I disagreed with the GBD approach). More generally, my paper with Robert Omberg, Is it possible to prepare for a pandemic? (open) finds that nations with universal health care, for example, didn’t have fewer excess deaths.

The bottom line is that vaccines worked and everything else was a sideshow. Had we approved the vaccines even 5 weeks earlier and delivered them to the nursing homes, we could have saved 14,000 lives and had we vaccinated nursing home residents just 10 weeks earlier, before the vaccine was approved, as Deborah Birx had proposed, we might have saved 40,000 lives. Nevertheless, Operation Warp Speed was the shining jewel of the pandemic. The lesson is that we should fund further vaccine R&D, create a library of prototype vaccines against potential pandemic threats, streamline our regulatory systems for rapid response, agree now on protocols for human challenge trials and keep warm rapid development systems so that we can produce vaccines not in 11 months but in 100 days.

The Big Fail does a great service in critiquing those who stifled debate and in demanding a full public accounting of what happened–an accounting that has yet to take place.

Addendum 1: I have reviewed most of the big books on the pandemic including the National Covid Commission’s Lessons from the COVID WAR, Scott Gottlieb’s Uncontrolled Spread, Michael Lewis’s The Premonition, Andy Slavitt’s Preventable and Abutaleb and Paletta’s Nightmare Scenario.

Addendum 2: I also liked Nocera and McLean’s All the Devils are Here on the financial crisis. Sad to say that the titles could be swapped without loss of validity.

Carrying opioids in legal imports?

The U.S. opioid crisis is now driven by fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that currently accounts for 90% of all opioid deaths. Fentanyl is smuggled from abroad, with little evidence on how this happens. We show that a substantial amount of fentanyl smuggling occurs via legal trade flows, with a positive relationship between state-level imports and drug overdoses that accounts for 15,000-20,000 deaths per year. This relationship is not explained by geographic differences in “deaths of despair,” general demand for opioids, or job losses from import competition. Our results suggest that fentanyl smuggling via imports is pervasive and a key determinant of opioid problems

That is from a new NBER working paper by Timothy J. Moore, William W. Olney, and Benjamin Hansen. One core lesson seems to be that interdiction is largely a futile endeavor.

*Saints, Scholars, and Schizophrenics*

The author of this excellent book is Nancy Scheper-Hughes, and the subtitle is Mental Illness in Rural Ireland. One of the most interesting themes of this book is how life in rural Ireland became so “de-eroticized,” to use her word. Here is one bit:

Marriage in rural Ireland is, I suggest, inhibited by anomie, expressed in a lack of sexual vitality; familistic loyalties that exaggerate latent brother-sister incestuous inclinations; an emotional climate fearful of intimacy and mistrustful of love; and an excessive preoccupation with sexual purity and pollution, fostered by an ascetic Catholic tradition. That these impediments to marriage and to an uninhibited expression of sexuality also contribute to the high rates of mental illness among middle-aged bachelor farmers is implicit in the following interpretations and verified in the life history materials and psychological tests of these men.

And:

In the preceding pages I have drawn a rather grim portrait of Irish country life, one that differs markedly from previous ethnographic studies. Village social life and institutions are, I contend, in a state of disintegration, and villagers are suffering from anomie, of which the most visible sign is the spiraling schizophrenia. Traditional culture has become unadaptive, and the newly emerging cultural forms as yet lack integration. The sexes are locked into isolation and mutual hostility. Deaths and emigrations surpass marriages and births.

Recommended. This seminal book, republished and revised in 2001, but originally from the 1970s, would be much harder to write and publish today.

England is underrated, a continuing series

The UK has said it will refrain from regulating the British artificial intelligence sector, even as the EU, US and China push forward with new measures. The UK’s first minister for AI and intellectual property, Viscount Jonathan Camrose, said at a Financial Times conference on Thursday that there would be no UK law on AI “in the short term” because the government was concerned that heavy-handed regulation could curb industry growth.

Here is more from the FT. And also from the FT: “UK approves Crispr gene editing therapy in global first.“