Category: Medicine

Fluoride revisionism?

I am usually skeptical of such efforts, but Journal of Health Economics is quite a serious outlet:

Community water fluoridation has been named one of the 10 greatest public health achievements of the 20th century for its role in improving dental health. Fluoride has large negative effects at high doses, clear benefits at low levels, and an unclear optimal dosage level. I leverage county-level variation in the timing of fluoride adoption, combined with restricted U.S. Census data that link over 29 million individuals to their county of birth, to estimate the causal effects of childhood fluoride exposure. Children exposed to community water fluoridation from age zero to five are worse off as adults on indices of economic self-sufficiency (−1.9% of a SD) and physical ability and health (−1.2% of a SD). They are also significantly less likely to graduate high school (−1.5 percentage points) or serve in the military (−1.0 percentage points). These findings challenge existing conclusions about safe levels of fluoride exposure.

That new article is by Adam Roberts. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Northern Ireland fact of the day

The NHS in Northern Ireland is the worst in the UK. During the quarter April/June 2021, over 349,000 people were waiting for a first appointment, 53 percent for over a year, an increase of 39,000 for the same period in 2020. Adjusted for population size, waiting lists in Northern Ireland are 100 times greater than those in England, a country 50 times its size.

That is from the truly excellent Perils and Prospects of a United Ireland, by Padraig O’Malley. Imagine a detailed, thoughtful 500 pp. book on political issues you probably don’t care all that much about — is there any better way to study politics and political reasoning? Every page of this book offers substance.

Elsewhere, of course, we are told that reluctance to give up their health care system is a major reason why Irish reunification is not more popular in the North, and that holds for Catholics too.

This one will make the best non-fiction of the year list.

Incentives matter, the demand curve slopes downward, mental health edition

Since 2000, pharmaceuticals for common psychiatric conditions aged out of patent protection. After generic entry, supply increases as more sellers enter the market, leading to lower prices – about 80-85% less! Cheaper prescriptions and more treatment are the stated goal of policies to improve affordability.

…Drug prices definitely fell during this period. For the SSRI sertraline, consumer cost per month dropped from ~35 dollars in the mid-2000s to ~6 dollars by the mid 2010s. Total Medicaid spending on antidepressants peaked in 2004 ($2 billion) then declined through 2018 ($750 million). Authors of that paper note that “generic drug prices steadily decreased over time” while utilization increased. From 2013 to 2018, both out-of-pocket costs and total expenditures per prescription fill went down for antidepressants and antipsychotics. For antipsychotics, generic drug claims grew 35% from 2016 to 2021.

According to the DEA, total dispensing of stimulants jumped 58% from 2012 to 2022; note how this follows the generic entry of long-acting Ritalin (methylphenidate) and Adderall (amphetamine) products. More recently, stimulant prices shot up amid shortages.

And:

By the mid 2010s, people with psychiatric conditions were better able to afford mental health care. Young adults, now on their parents insurance, saw declining out of pocket costs for behavioral health in particular. For people aged 18-25, “mental health treatment increased by 5.3 percentage points relative to a comparison group of similar people ages 26–35.” Even for employer plans, in-network prices and cost-sharing decreased from 2007 to 2017…

Here is the full essay by AffectiveMedicine. It has numerous other points of interest.

Model this

Doctors were given cases to diagnose, with half getting GPT-4 access to help. The control group got 73% right & the GPT-4 group 77%. No big difference.

But GPT-4 alone got 92%. The doctors didn’t want to listen to the AI.

Here is more from Ethan Mollick. And now the tweet is reposted with (minor) clarifications:

A preview of the coming problem of working with AI when it starts to match or exceed human capability: Doctors were given cases to diagnose, with half getting GPT-4 access to help. The control group got 73% score in diagnostic accuracy (a measure of diagnostic reasoning) & the GPT-4 group 77%. No big difference. But GPT-4 alone got 88%. The doctors didn’t change their opinions when working with AI.

A new schizophrenia drug

One of the most satisfying aspects of covering biotech as long as I have is the opportunity to report on the long arc of drug development, from start to finish. It’s not always pretty, and more often than not, it ends badly.

But KarXT, now Cobenfy, is one of those drug stories with a happy ending. I remember talking to Steven Paul in 2019 for a story about the phase 2 results, which were pretty remarkable. Paul was excited about what KarXT might mean for people with schizophrenia, but he was cautious because, as he warned me at the time, clinical trials for psychiatric conditions are extraordinarily difficult to replicate. Let’s wait to see what KarXT does in Ph3 trials, he said.

Now, we know.

It’s been cool to follow and report on the KarXT story all these years. From PureTech to Karuna to Bristol Myers Squibb, and now, to approval, where Cobenfy will have a meaningful impact on people living with schizophrenia.

That is from Adam Feuerstein, who also links to StatNews:

The drug, called Cobenfy, will be sold by Bristol Myers Squibb. It was developed by the biotech company Karuna Therapeutics, which Bristol acquired for $14 billion last year.

Supply is elastic, people. And we live in a (potential) golden age for biomedical advances.

On the price of Ozempic

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

As for consumer prices for the current obesity drugs, they are not as high as is often reported, once the various ways to get a discount are taken into account. Despite reports that the drugs cost $1,000 per month, the reality is more favorable. Even putting aside insurance coverage, readily available discounts can cut that price in half. Eli Lilly & Co. recently introduced online sales of Zepbound vials for $399 a month.

Lurking in the background are “compounded” versions of these drugs, which are pharmacy-produced copies, permitted by law when there is a shortage of the core drugs. These compounds do not undergo the same inspection processes as the brand names, and their safety and efficacy has been questioned. But they are easy to get and relatively cheap. This is an example of competition, however imperfect and in need of oversight, lowering prices — and in a less clumsy manner than a government price control.

Are we right now getting anything close to optimal price discrimination, or not?

“Despair” and Death in the United States

Increases in “deaths of despair” have been hypothesized to provide an important source of the adverse mortality experiences of some groups at the beginning of the 21st century. This study examines this possibility and uncovers the following primary findings. First, mental health deteriorated between 1993 and 2019 for all population subgroups examined. Second, these declines raised death rates and contributed to the adverse mortality trends experienced by prime-age non-Hispanic Whites and, to a lesser extent, Blacks from 1999-2019. However, worsening mental health is not the predominant explanation for them. Third, to extent these relationships support the general idea of “deaths of despair”, the specific causes comprising it should be both broader and different than previously recognized: still including drug mortality and possibly alcohol deaths but replacing suicides with fatalities from heart disease, lower respiratory causes, homicides, and conceivably cancer. Fourth, heterogeneity in the consequences of a given increase of poor mental health are generally more important than the sizes of the changes in poor mental health in explaining Black-White differences in the overall effects of mental health on mortality.

Sweden fact of the day

However, following the start of PhD studies, the use of psychiatric medication among PhD students increases substantially. This upward trend continues throughout the course of PhD studies, with estimates showing a 40 percent increase by the fifth year compared to pre-PhD levels. After the fifth year, which represents the average duration of PhD studies in our sample, we observe a notable decrease in the utilization of psychiatric medication.

Here is the article, via Jesse. Here are some relevant tweets. It doesn’t have to be causal to be interesting!

The US Has Low Prices for Most Prescription Drugs

The US has high prices for branded drugs but it has some of the lowest prices for generic drugs in the world and generic drugs are 90% of prescriptions. I’ve been saying this for years but here is the latest study:

U.S. prices for brand-name originator drugs were 422 percent of prices in comparison countries, while U.S. unbranded generics, which we found account for 90 percent of U.S. prescription volume, were on average cheaper at 67 percent of prices in comparison countries, where on average only 41 percent of prescription volume is for unbranded generics. U.S. prices for brand-name drugs remained 308 percent of prices in other countries even after adjustments to account for rebates paid by drug companies to U.S. payers and their pharmacy benefit managers.

Branded drugs are expensive but that is why we have insurance which works reasonably well, albeit far from perfectly. For example, insurance and the low price of generics is one reason that out-of-pocket costs for medical are low in the United States.

If you don’t want to pay high prices for branded drugs just use generics! As I wrote 20 years ago, in what was called a heartless and cruel post:

People talk about the high price of pharmaceuticals as if high prices lasted forever. In fact, within a year of the expiration of a pharmaceutical’s patents, prices will typically fall by more than 50 percent as generic producers enter the market. Patents nominally last for 20 years but the effective patent life is much lower because patents are typically granted years before a product has cleared FDA review. The effective patent life of the average new pharmaceutical in the 1990s averaged just 12 years [new reference for today, 13.5 years, AT]. Competition from competing but non-infringing pharmaceuticals makes the de facto patent life even shorter.

Thus, my response to the seniors and others clamoring for lower pharmaceutical prices is to be more patient. Does this sound harsh? Consider this, the people who are demanding price controls are not simply asking for lower drug prices they are asking for lower prices on the newest drugs. Lower prices for drugs introduced 15 years ago are already here. Remember, those drugs were recently considered the very best modern medicine has to offer, so it’s not like I am expecting those who can’t afford the newer medicines to go back to using leeches.

Price controls or other such plans such as reimportation may bring cheaper pharmaceuticals for a short period but we will then have a much smaller supply of new drugs forever. Only the shortsighted would buy that prescription.

Don’t fail the marshmallow test people!

People get upset when I say just use generics–shouldn’t everyone have access to the very best pharmaceuticals! Yes! But that illustrates another point–these drugs are worth the price!

Hat tip: Steve.

USA fact of the day

For the first time in decades, public health data shows a sudden and hopeful drop in drug overdose deaths across the U.S.

“This is exciting,” said Dr. Nora Volkow, head of the National Institute On Drug Abuse [NIDA], the federal laboratory charged with studying addiction. “This looks real. This looks very, very real.”

National surveys compiled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention already show an unprecedented decline in drug deaths of roughly 10.6 percent. That’s a huge reversal from recent years when fatal overdoses regularly increased by double-digit percentages.

Some researchers believe the data will show an even larger decline in drug deaths when federal surveys are updated to reflect improvements being seen at the state level, especially in the eastern U.S.

“In the states that have the most rapid data collection systems, we’re seeing declines of twenty percent, thirty percent,” said Dr. Nabarun Dasgupta, an expert on street drugs at the University of North Carolina.

According to Dasgupta’s analysis, which has sparked discussion among addiction and drug policy experts, the drop in state-level mortality numbers corresponds with similar steep declines in emergency room visits linked to overdoses.

Here is the link, via Anna Gat of Interintellect.

USA fact of the day

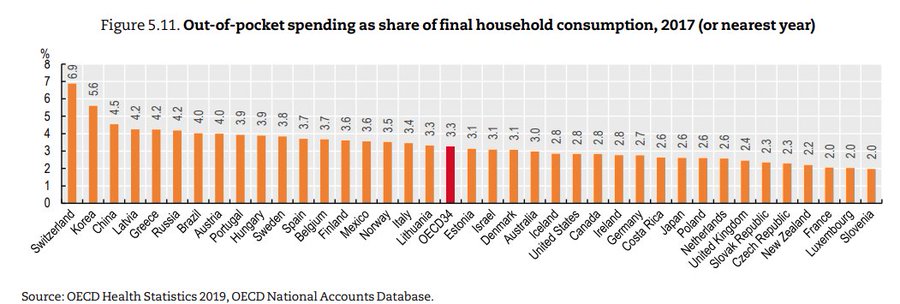

Surprised to learn that the US is below the OECD average for out of pocket health care spending as a fraction of per capita consumption, with virtually the same % as Canada.

That is Jason Abaluck, via the wisdom of Garett Jones.

Peer Approval to Address Drug Shortages

Reuters: Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company said…that it is working with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to import and distribute penicillin in the country temporarily….Cuban’s Cost Plus will import Lentocilin brand penicillin powder marketed by Portugal-based Laboratórios Atral S.A.

There are two remarkable items in the above passage. First, there is a shortage of penicillin in the United States! Crazy. The second remarkable item is that the FDA has authorized the temporary importation of penicillin from Portugal. In other words, the FDA will accept the EMA’s authorization of penicillin as equivalent to its own, at least for the purposes of alleviating the shortage. That’s good. What is needed, however, is a more permanent form of peer-approval.

I have long advocated for peer approval or reciprocity for any drug or device approved in a peer country but notice that this form of peer approval is only for drugs already approved in the United States. Thus, the approval is really only for labeling and manufacturing, a pretty small ask.

Peer approval for imports would also help to discipline domestic firms who sometimes take advantage of monopoly power to jack up prices. Indeed, you may recall Martin Shkreli and the massive price increases for Daraprim (Pyrimethamine) to $750 a pill when the same pill was available in Europe for $1 or less and in India for 10 cents. Importation would have solved that problem entirely.

Mental health trajectories in the UK

Yes, there is a human capital crisis of sorts:

We show the incidence of mental ill-health has been rising especially among the young in the years and especially so in Scotland. The incidence of mental ill-health among young men in particular, started rising in 2008 with the onset of the Great Recession and for young women around 2012. The age profile of mental ill-health shifts to the left, over time, such that the peak of depression shifts from mid-life, when people are in their late 40s and early 50s, around the time of the Great Recession, to one’s early to mid-20s in 2023. These trends are much more pronounced if one drops the large number of proxy respondents in the UK Labour Force Surveys, indicating fellow family members understate the poor mental health of respondents, especially if those respondents are young. We report consistent evidence from the Scottish Health Surveys and UK samples from Eurobarometer surveys. Our findings are consistent with those for the United States and suggest that, although smartphone technologies may be closely correlated with a decline in young people’s mental health, increases in mental ill-health in the UK from the late 1990s suggest other factors must also be at play.

That is from a new NBER working paper by David G. Blanchflower, Alex Bryson, and David N.F. Bell. By the way, on the “smart phone causality” issue, here are some recent musings. And a response, and a response to that.

Note that in my rough, first-order human capital hypothesis, the variance is rising. So the top achievers are considerably more impressive, but that also means the number of problematic cases, toward the bottom of the distribution, is rising as well.

*Self-Help is Like a Vaccine*, by Bryan Caplan

This is one of the best and most correct self-help books. Bryan describes it as follows:

I’ve been writing economically-inspired self-help essays for almost two decades, Self-Help Is Like a Vaccine compiles the most helpful 5-7% of my advice.

Of Bryan’s recent string of books, this is the one I agree with the most. Bryan offers some further description:

Like my other books of essays, Self-Help Is Like a Vaccine is divided into four parts.

- The first, “Unilateral Action,” argues that despite popular nay-saying and “Can’t-Do” mentalities, you have a vast menu of unexplored choices. Where there’s a will, there’s a way. While most “minorities of one” are fools, cautious experimentation and appreciation of good track records, not conformism, is the wise response.

- The next section, “Life Hacks,” offers a bunch of specific suggestions for improving your life. Only one hack has to work out to instantly justify your purchase of the book.

- “Professor Homeschool” brings together all of my best pieces on teaching my own kids. I have over a decade’s experience: I taught the twins for grades 7-12, all four kids for Covid, and my 10th-grader is working one room away from me as I write. Except during Covid, homeschooling is a fair bit of extra work, but if you’re still curious, I’ve got a pile of time-tested advice.

- I close the book with “How to Dale Carnegie.” As you may know, I’m a huge fan of his classic How to Win Friends and Influence People. Not because I’m naturally a people-pleaser; I’m not. But with Dale’s help, I have managed to make thousands of friends all over the planet. Few skills are more useful, both emotionally and materially.

You can buy the book here.

Mpox Vaccines Stuck in Limbo: WHO is at Fault

In 2022, Mpox, a viral disease endemic to parts of Africa and primarily transmitted through close contact—especially sexual contact between men—spread to developed countries, including the United States. The U.S. saw over 30,000 cases and approximately 58 deaths. Despite two available vaccines there was not nearly enough supply to vaccinate even the high-risk populations. Fortunately, health authorities adopted vaccination strategies my colleagues and I had recommended for COVID such as first doses first and fractional dosing. For example, several small studies (e.g. here and here) suggested that 1/5 doses delivered intradermally could be effective and the FDA, EMA, and the UK all recommended this fractional dosing strategy. As result, the US was able to vaccinate around 800,000 people and the epidemic ended (natural immunity and other preventive measures also played a role).

Unfortunately, a new Mpox variant is now spreading in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and nearby countries. Here’s the crazy part: despite declaring Mpox a public health emergency on August 14, the WHO has not approved any Mpox vaccines. You might think, “Who cares what the WHO authorizes?” After all, the FDA, EMA, and the UK have all granted emergency approval. But here’s the catch: the WHO’s approval is crucial for GAVI, the vaccine alliance that donates vaccines to developing countries. Without WHO approval, GAVI is reluctant to provide vaccines to the Congo. To add insult to injury, the Congo itself has approved the Jynneos and LC16 vaccines. Yet, the WHO refuses to authorize and GAVI to donate these vaccines, citing vague concerns about safety and efficacy.

Stephanie Nolen at the NYTimes has a very good piece on this mess:

Three years after the last worldwide mpox outbreak, the W.H.O. still has neither officially approved the vaccines — although the United States and Europe have — nor has it issued an emergency use license that would speed access.

One of these two approvals is necessary for UNICEF and Gavi, the organization that helps facilitate immunizations in developing nations, to buy and distribute mpox vaccines in low-income countries like Congo.

While high-income nations rely on their own drug regulators, such as the Food and Drug Administration in the United States, many low- and middle-income countries depend on the W.H.O. to judge what vaccines and treatments are safe and effective, a process called prequalification.

But the organization is painfully risk-averse, concerned with a need to protect its trustworthiness and ill-prepared to act swiftly in emergencies, said Blair Hanewall…

In addition, no one has followed the other practice my colleagues and I recommended for COVID (which Operation Warp Speed did), namely advance market commitments. So the vaccine manufacturers have basically been twiddling their thumbs and not gearing up for greater production. (The Congo can also be faulted for not buying more on their own account.)

All of this means that when the WHO does authorize and the vaccines begin to flow, we will still desperately need strategies like fractional dosing.

Hat tip: Ben H. and special thanks to Witold Wiecek.