Category: Medicine

A Weighty Economics Puzzle

Yesterday a new study was released showing that patients on Eli Lilly’s Zepbound (tirzepatide) lost weight but regained a meaningful percentage after being switched to placebo. Eli Lilly stock “tumbled” on the news, e.g. here and here or see below. In other words, Eli Lilly stock fell when investors learned that to keep the weight off patients would have to continue to take Zepbound for life. Hmmm…that certainly violates what the man in the street thinks about pharmaceutical companies and profits. Chris Rock, for example, says the money isn’t in the cure, the money’s in the comeback. If so, shouldn’t this have been great news for Eli Lilly?

So why did Eli Lilly stock fall? Could it be that the Chris Rock and the man in the street are wrong? I will leave this as an exercise for the reader.

No Child Left Behind: Accelerate Malaria Vaccine Distribution!

My post What is an Emergency? The Case for Rapid Malaria Vaccination, galvanized the great team at 1DaySooner. Here is Zacharia Kafuko writing at Foreign Policy:

Right now, enough material to make 20 million doses of a lifesaving malaria vaccine is sitting on a shelf in India, expected to go unused until mid-2024. Extrapolating from estimates by researchers at Imperial College London, these doses—enough for 5 million children—could save more than 31,000 lives, at a cost of a little more than $3,000 per life. But current plans by the World Health Organization to distribute the vaccine are unclear and have been criticized as lacking urgency.

…Vaccine deployment and licensure is an incredibly complex scientific, legal, and logistical process involving numerous parties across international borders. Roughly speaking, after the WHO recommends vaccines (such as R21), it must also undertake a prequalification process and receive recommendations from its Strategic Advisory Group of Experts before UNICEF is allowed to purchase vaccines. Then Gavi—a public-private global health alliance—can facilitate delivery by national governments, which must propose their anticipated demand to Gavi and make plans to distribute the vaccines.

Prequalification can take as long as 270 days after approval. However, the COVID-19 vaccines were rolled out within weeks of WHO’s approval, using the separate EUL process rather than the more standard prequalification process that R21 is now undergoing.

For COVID-19 vaccines, EUL was available because the pandemic was undeniably an emergency. Given the staggering scale of deaths of children in sub-Saharan Africa every year, shouldn’t we also be treating malaria vaccine deployment as an emergency?

The R21 malaria vaccine does not legally qualify for EUL because malaria already has a preventive and curative toolkit available. My concern is that this normalizes the deaths of hundreds of thousands of children each year in Africa.

We can move more quickly and save more lives, if we have the will.

Don’t Let the FDA Regulate Lab Tests!

I have been warning about the FDA’s power grab over lab developed tests. Lab developed tests have never been FDA regulated except briefly during the pandemic emergency when such regulation led to catastrophic consequences. Catastrophic consequences that had been predicted in advanced by Paul Clement and Lawrence Tribe. Despite this, for reasons I do not understand, the FDA plan is marching forward but many other people are starting to warn of dire consequences. Here, for example, is the executive summary from a letter by ARUP Laboratories, a non-profit enterprise of the University of Utah Department of Pathology:

ARUP urges the FDA to withdraw the proposed rule:

- The FDA proposal will reduce, an in many cases eliminate, access to safe and essential testing services, particularly for patients with rare diseases.

- Laboratory-developed tests are not devices as defined by the Medical Device Amendments of 1976, nor are clinical laboratories acting as manufacturers.

- The FDA does not have the statutory authority to regulate laboratory-developed tests.

- The FDA does not have the authority to regulate states, or state-owned entities. This is particularly relevant for the proposed rule regarding academic medical centers.

- The FDA’s regulatory impact analysis is flawed in its design, source information, methods. and conclusions, and it systematically overestimates purported benefits of the proposed rule and dramatically underestimates its cost to society, the healthcare industry, and the ability to provide ongoing essential laboratory services to patients.

- The proposed rule would significantly limit the ability of clinical laboratories to respond quickly to future pandemic, chemical, and/or radiologic public health threats.

- The proposed rule would not be easily implementable, and it would create an insurmountable backlog of submissions that would hinder diagnostic innovation.

- The proposed rule limits the practice of laboratory medicine.

- The FDA has not evaluated less restrictive, easily administered alternatives, such as CLIA reform. This is particularly relevant for common test modifications used in most hospital and academic medical center settings.”

Here is the American Hospital Association:

…we strongly believe that the FDA should not apply its device regulations to hospital and health system LDTs. These tests are not devices; rather, they are diagnostic tools developed and used in the context of patient care. As such, regulating them using the device regulatory framework would have an unquestionably negative impact on patients’ access to essential testing. It would also disrupt medical innovation in a field demonstrating tremendous benefits to patients and providers.

Here is Mass General Brigham, a non-profit hospital system, affiliated with Harvard, and the largest hospital-based research enterprise in the United States:

…we are concerned with the heavy regulatory burden of this proposal. In implementing any regulatory structure, policymakers must consider if the benefits outweigh the costs. Given that FDA predicts 50 percent of tests would require premarket review, and 5 percent will require premarket approval, we have serious concerns that the costs may outweigh the benefits. Given that many LDTs are hospital-based and will never be commercialized, hospitals will have little incentive or ability to develop future LDTs under this proposed rule as they will have little to no opportunity to offset the costs associated with these new regulatory requirements. We are concerned that the regulatory burden could have significant implications on responsible innovation especially for LDTs targeting rare conditions, or public health emergencies.

Two U.S. public lab directors personally reached out to me to ask me amplify the warning. Consider it amplified!

Today is the last day for public comment. Get your comments in!

One Reason Why American Health Care is Expensive

tl/dr; Canadian woman is diagnosed with cancer, told she has 2 years to live at most, that she is not a candidate for surgery but would she like medical help committing suicide? She declines, comes to the United States, spends a lot of money, and is treated within weeks. Her health insurance is refusing to pay.

Global News: Ducluzeau said her family doctor told her that with this type of cancer, they usually do a procedure called HIPEC, which involves delivering high doses of chemotherapy into the abdomen to kill the cancer cells. But when she saw the consulting surgeon at the BC Cancer Agency in January, she said she was told she was not a candidate for surgery.

“Chemotherapy is not very effective with this type of cancer,” Ducluzeau said the surgeon told her. “It only works in about 50 per cent of the cases to slow it down. And you have a life span of what looks like to be two months to two years. And I suggest you talk to your family, get your affairs in order, talk to them about your wishes, which was indicating, you know, whether you want to have medically assisted dying or not.”

…Her brother contacted his mother-in-law who lives in Taiwan and she was able to get some advice from an oncologist there, after only waiting an hour. That oncologist confirmed that HIPEC was the treatment for Ducluzeau’s cancer. She set up a Zoom call with that oncologist later that week but then she found out about Dr. Armando Sardi at the Mercy Medical Center in Baltimore, Maryland.

“I had an appointment to speak with him via Zoom as well within a week and then also in Washington State,” she explained. “So there were two hospitals in Taiwan, one in Washington State and one in Baltimore that were able to take me as a patient.”

Ducluzeau decided to get treatment with Sardi in Baltimore.

…“I had to fly to California to get one of my diagnostic scans done there, a PET scan, because I wasn’t getting in here and I had to pay to have another CT scan done when I got to Baltimore because they couldn’t get it in time before I left,” she said.

Before she left, Ducluzeau said she called BC Cancer to ask how long it might be to see the oncologist was told it could be weeks, months, or longer, they had no idea.

“And I said, ‘Well, will it help if my doctor phones on my behalf?’ And they said, ‘no’. And my doctor submitted my referral again and still no word. No word at all from (BC Cancer) until after I flew to Baltimore, had my surgery and got home.”

With the help of a surgeon in Vancouver, Ducluzeau finally got a telephone appointment with an oncologist at BC Cancer for the middle of March – two-and-a-half months after receiving her diagnosis and the news that she may only have two months to two years to live.

…The BC Cancer Agency is refusing to provide documentation that would allow Ducluzeau to be reimbursed for the cost of out-of-country care, citing she did not proceed with additional investigations, such as a colonoscopy and laparoscopy.

“Universal healthcare really doesn’t exist,” Ducluzeau said. “My experience is it’s ‘do it yourself’ health care and GoFundMe health care.

The Big Fail

The Big Fail, Joe Nocera and Bethany McLean’s new book about the pandemic, is an angry book. Rightly so. It decries the way the bien pensant, the self-righteously conventional,  were able to sideline, suppress and belittle other voices as unscientific, fraudulent purveyors of misinformation. The Big Fail gives the other voices their hearing— Martin Kulldorff, Sunetra Gupta, Jay Bhattacharya and Emily Oster are recast not as villains but as heroes; as is Ron DeSantis who is given credit for bucking the conventional during the pandemic (Nocera and McLean wonder what happened to the data-driven DeSantis, as do I.)

were able to sideline, suppress and belittle other voices as unscientific, fraudulent purveyors of misinformation. The Big Fail gives the other voices their hearing— Martin Kulldorff, Sunetra Gupta, Jay Bhattacharya and Emily Oster are recast not as villains but as heroes; as is Ron DeSantis who is given credit for bucking the conventional during the pandemic (Nocera and McLean wonder what happened to the data-driven DeSantis, as do I.)

Amazingly, even as highly-qualified epidemiologists and economists were labelled “anti-science” for not following the party line, the biggest policy of them all, lockdowns, had little to no scientific backing:

…[lockdowns] became the default strategy for most of the rest of the world. Even though they had never been used before to fight a pandemic, even though their effectiveness had never been studied, and even though they were criticized as authoritarian overreach—despite all that, the entire world, with a few notable exceptions, was soon locking down its citizens with varying degrees of severity.

In the United States, lockdowns became equated with “following the science.” It was anything but. Yes, there were computer models suggesting lockdowns would be effective, but there were never any actual scientific studies supporting the strategy. It was a giant experiment, one that would bring devastating social and economic consequences.

The narrative lined up “scientific experts” against “deniers, fauxers, and herders” with the scientific experts united on the pro-lockdown side (the following has no indent but draws from an earlier post). But let’s consider. In Europe one country above all others followed the “ideal” of an expert-led pandemic response. A country where the public health authority was free from interference from politicians. A country where the public had tremendous trust in the state. A country where the public were committed to collective solidarity and public welfare. That country, of course, was Sweden. Yet in Sweden the highly regarded Public Health Agency, led by state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell, an expert in infectious diseases, opposed lockdowns, travel restrictions, and the general use of masks.

It’s important to understand that Tegnell wasn’t an outsider marching to his own drummer, anti-lockdown was probably the dominant expert opinion prior to COVID. In a 2006 review of pandemic policy, for example, four highly-regarded experts argued:

It is difficult to identify circumstances in the past half-century when large-scale quarantine has been effectively used in the control of any disease. The negative consequences of large-scale quarantine are so extreme (forced confinement of sick people with the well; complete restriction of movement of large populations; difficulty in getting critical supplies, medicines, and food to people inside the quarantine zone) that this mitigation measure should be eliminated from serious consideration.

Travel restrictions, such as closing airports and screening travelers at borders, have historically been ineffective.

….a policy calling for communitywide cancellation of public events seems inadvisable.

The authors included Thomas V. Inglesby, the Director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, one of the most highly respected centers for infectious diseases in the world, and D.A. Henderson, the legendary epidemiologist widely credited with eliminating smallpox from the planet.

Nocera and McLean also remind us of the insanity of the mask debate, especially in the later years of the pandemic.

But by the spring of 2022, the CDC had dropped its mask recommendations–except, incredibly, for children five and under, who again, were the least likely to be infected.

…Once again it was Brown University economist Emily Oster who pointed out how foolish this policy was…The headline was blunt: Masking Policy is Incredibly Irrational Right Now. In this article she noted that even as the CDC had dropped its indoor mask requirements for kids six and older, it continued to maintain the policy for younger children. “Some parents of young kids have been driven insane by this policy,” Oster wrote, “I sympathize–because the policy is completely insane…”

As usual, her critics jumped all over her. As usual, she was right.

Naturally, I don’t agree with everything in the Big Fail. Nocera and McLean, for example, are very negative on the role of private equity in hospitals and nursing homes. My view is that any theory of what is wrong with American health care is true because American health care is wrong in every possible way. Still, I don’t see private equity as a driving force. It’s easy to find examples where private equity owned nursing homes performed poorly but so did many other nursing homes. More systematic analyses find that PE owned nursing homes performed about the same, worse or better than other nursing homes. Personally, I’d bet on about the same overall. Covid in the Nursing Homes: The US Experience (open), my paper with Markus Bjoerkheim, shows that what mattered more than anything else was simply community spread (see also this paper for the ways in which I disagreed with the GBD approach). More generally, my paper with Robert Omberg, Is it possible to prepare for a pandemic? (open) finds that nations with universal health care, for example, didn’t have fewer excess deaths.

The bottom line is that vaccines worked and everything else was a sideshow. Had we approved the vaccines even 5 weeks earlier and delivered them to the nursing homes, we could have saved 14,000 lives and had we vaccinated nursing home residents just 10 weeks earlier, before the vaccine was approved, as Deborah Birx had proposed, we might have saved 40,000 lives. Nevertheless, Operation Warp Speed was the shining jewel of the pandemic. The lesson is that we should fund further vaccine R&D, create a library of prototype vaccines against potential pandemic threats, streamline our regulatory systems for rapid response, agree now on protocols for human challenge trials and keep warm rapid development systems so that we can produce vaccines not in 11 months but in 100 days.

The Big Fail does a great service in critiquing those who stifled debate and in demanding a full public accounting of what happened–an accounting that has yet to take place.

Addendum 1: I have reviewed most of the big books on the pandemic including the National Covid Commission’s Lessons from the COVID WAR, Scott Gottlieb’s Uncontrolled Spread, Michael Lewis’s The Premonition, Andy Slavitt’s Preventable and Abutaleb and Paletta’s Nightmare Scenario.

Addendum 2: I also liked Nocera and McLean’s All the Devils are Here on the financial crisis. Sad to say that the titles could be swapped without loss of validity.

Carrying opioids in legal imports?

The U.S. opioid crisis is now driven by fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that currently accounts for 90% of all opioid deaths. Fentanyl is smuggled from abroad, with little evidence on how this happens. We show that a substantial amount of fentanyl smuggling occurs via legal trade flows, with a positive relationship between state-level imports and drug overdoses that accounts for 15,000-20,000 deaths per year. This relationship is not explained by geographic differences in “deaths of despair,” general demand for opioids, or job losses from import competition. Our results suggest that fentanyl smuggling via imports is pervasive and a key determinant of opioid problems

That is from a new NBER working paper by Timothy J. Moore, William W. Olney, and Benjamin Hansen. One core lesson seems to be that interdiction is largely a futile endeavor.

*Saints, Scholars, and Schizophrenics*

The author of this excellent book is Nancy Scheper-Hughes, and the subtitle is Mental Illness in Rural Ireland. One of the most interesting themes of this book is how life in rural Ireland became so “de-eroticized,” to use her word. Here is one bit:

Marriage in rural Ireland is, I suggest, inhibited by anomie, expressed in a lack of sexual vitality; familistic loyalties that exaggerate latent brother-sister incestuous inclinations; an emotional climate fearful of intimacy and mistrustful of love; and an excessive preoccupation with sexual purity and pollution, fostered by an ascetic Catholic tradition. That these impediments to marriage and to an uninhibited expression of sexuality also contribute to the high rates of mental illness among middle-aged bachelor farmers is implicit in the following interpretations and verified in the life history materials and psychological tests of these men.

And:

In the preceding pages I have drawn a rather grim portrait of Irish country life, one that differs markedly from previous ethnographic studies. Village social life and institutions are, I contend, in a state of disintegration, and villagers are suffering from anomie, of which the most visible sign is the spiraling schizophrenia. Traditional culture has become unadaptive, and the newly emerging cultural forms as yet lack integration. The sexes are locked into isolation and mutual hostility. Deaths and emigrations surpass marriages and births.

Recommended. This seminal book, republished and revised in 2001, but originally from the 1970s, would be much harder to write and publish today.

England is underrated, a continuing series

The UK has said it will refrain from regulating the British artificial intelligence sector, even as the EU, US and China push forward with new measures. The UK’s first minister for AI and intellectual property, Viscount Jonathan Camrose, said at a Financial Times conference on Thursday that there would be no UK law on AI “in the short term” because the government was concerned that heavy-handed regulation could curb industry growth.

Here is more from the FT. And also from the FT: “UK approves Crispr gene editing therapy in global first.“

The Amazing Vernon Smith

You can find Vernon Smith hard at work at his computer by 7:30 each morning, cranking out 10 solid hours of writing and researching every day.

His job is incredibly demanding — he is currently on the faculty of both the business and law schools at Chapman University. But the hard work pays off: Smith’s research is consistently ranked as the most-cited work produced at the school — a testament to his ongoing academic influence and success. He manages his job and research work while also coauthoring books and traveling around the country to deliver lectures.

It’s a remarkable level of productivity, made all the more remarkable by one simple fact: Vernon Smith is 96 years old.

Smith, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences at the tender age of 75, says he feels the same passion as he did then, and even as he did when he embarked on his career more than seven decades ago.

That’s from the AARP on SuperAgers. In addition to all that, Vernon “is one of 1,600 participants in the University of California, Irvine’s 90+ Study, a research project examining both successful aging and dementia in people age 90 and older.”

Vernon was always one of our sharpest and most productive colleagues. He remains an inspiration.

Pharmaceutical Price Controls and the Marshmallow Test

The pharmaceutical market is in turmoil. On the one hand we have what looks like a golden age of medicine with millions of lives saved by COVID vaccines, a leap in mRNA technology, excellent new obesity and blood sugar drugs, breakthroughs in cancer treatments and more. On the other hand, the Inflation Reduction Act includes the most extensive price controls on pharmaceuticals we have ever seen in the United States.

In Washington-speak the “Inflation Reduction Act” requires HHS to “negotiate” drug prices for Medicare Part D and Part B to establish a maximum “fair” price. In reality there is no negotiation–firms who refuse to negotiate are hit with huge taxes. The “negotiation,” if you want to call it that, is “your money or your life” and fairness has little to do with it. The IRA also requires very costly inflation rebates, i.e. a price control/tax. In essence, the IRA is a taking; for drugs with a large Medicare market it is similar to abrogating patents to 9 years for small molecule drugs and 13 years for biologics. For the included drugs there will be a significant reduction in revenues. Moreover, we don’t yet know whether the plan will be extended to more and more drugs. There is significant uncertainty affecting the entire market. What will be situation in 10 years? Will the US be like Europe?

Reduced revenues mean less R&D. The value of extending life is very high and so in my view medical R&D is underprovided. Thus, price controls are taking us in the wrong direction.

The positive effects of price controls are immediate and easy to see: Prices are reduced.

The negative effects of price controls take time and are harder to see. Namely:

- Fewer drugs for Medicare market.

- Less research on post-approval indications and confirmatory trials.

- Reduced incentive for generics to enter quickly.

- Most importantly: Less R&D spending leading to fewer new drugs, a reduced pharmaceutical armory, lower life expectancy and higher morbidity. By one calculation, ~135 fewer new drugs through to 2039 (see also here and here and here and here).

- Fewer new drugs means more spending on physicians and hospitals so in the long run price controls may not even save money! (Most prescriptions are for generics. Drugs fall greatly in price when they go generic but physicians and hospitals never go generic!)

Price controls are a classic example of political myopia. Price controls, like rent controls and deficit financing, have modest benefits now and big future costs and thus they are supported by politicians who want to be elected now. Unfortunately, current citizens don’t forecast the future well and future citizens don’t have a vote so it’s easy to create big future costs without engaging an opposition.

The emergence of groundbreaking pharmaceuticals and the increasing implementation of price controls are probably related trends. Everyone wants the great new pharmaceuticals without paying for them. We need to think more long-term–we have much more to gain from a continuing flow of new pharmaceuticals than from lower prices on the last generation. Don’t forget that children who fail the marshmallow test do less well later in life. Well, our government is failing the marshmallow test, big time.

Pharmaceutical price controls driven by myopia and the failure to delay gratification are greatly harming future patients.

Are dementia rates falling?

A study published in 2020, which drew together multiple pieces of research to track the health of almost 50,000 over-65s, showed the incidence rate of new cases of dementia in Europe and North America had dropped 13 per cent per decade over the past 25 years — a decline that was consistent across all the studies.

For Albert Hofman, who chairs the department of epidemiology at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, the research points to one conclusion: “The absolute risk [of developing dementia] is lower now” than it was 30 years ago. Now, there are early signs that the same phenomenon may be emerging in Japan, a striking development in one of the world’s most aged populations, suggesting that the downward trend is becoming more widespread…

While emphasising that the reasons for the reduction in incidence are not yet fully understood, Hofman believes better cardiovascular health is likely to be a significant factor given the proven links between the two.

Here is more from Sarah Neville at the FT. Maybe that is where the Flynn effect has been hiding!

Covid vaccines and mortality

The global COVID-19 vaccination campaign is the largest public health campaign in history, with over 2 billion people fully vaccinated within the first 8 months. Nevertheless, the impact of this campaign on all-cause mortality is not well understood. Leveraging the staggered rollout of vaccines, we find that the vaccination campaign across 141 countries averted 2.4 million excess deaths, valued at $6.5 trillion. We also find that an equitable counterfactual distribution of vaccines, with vaccination in each country proportional to its population, would have saved roughly 670,000 more lives. However, this distribution approach would have reduced the total value of averted deaths by $1.8 trillion due to redistribution of vaccines from high-income to low-income countries.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Virat Agrawal, Neeraj Sood, and Christopher M. Whaley.

The culture (polity?) that is Dutch

Several people with autism and intellectual disabilities have been legally euthanized in the Netherlands in recent years because they said they could not lead normal lives, researchers have found.

The cases included five people younger than 30 who cited autism as either the only reason or a major contributing factor for euthanasia, setting an uneasy precedent that some experts say stretches the limits of what the law originally intended.

In 2002, the Netherlands became the first country to allow doctors to kill patients at their request if they met strict requirements, including having an incurable illness causing “unbearable” physical or mental suffering.

Between 2012 and 2021, nearly 60,000 people were killed at their own request, according to the Dutch government’s euthanasia review committee. To show how the rules are being applied and interpreted, the committee has released documents related to more than 900 of those people, most of whom were older and had conditions including cancer, Parkinson’s and ALS.

Here is the full story.

A Genius Award for Airborne Transmission

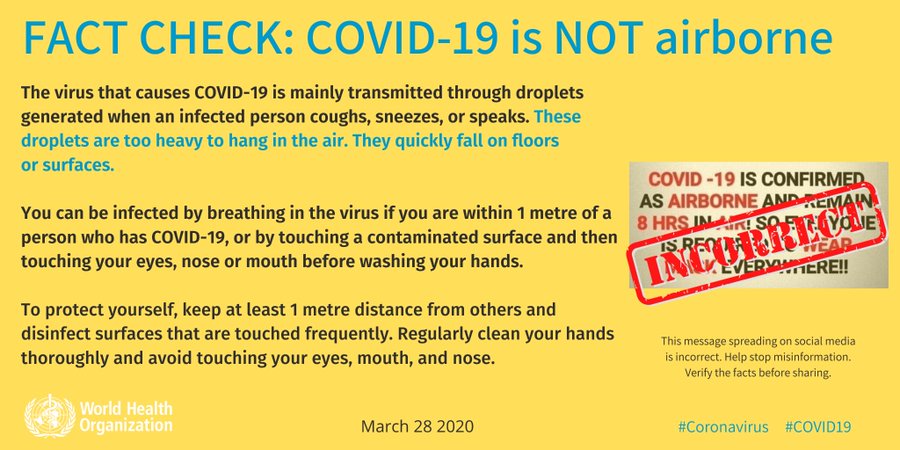

One of the strangest aspects of the pandemic was the early insistence by the WHO and the CDC that COVID was not airborne. “FACT: #COVID19 is NOT airborne.” the WHO tweeted on March 28, 2020, accompanied by a large graphic (at right). Even at that time, there was plenty of evidence that COVID was airborne. So why was the WHO so insistent that it wasn’t?

One of the strangest aspects of the pandemic was the early insistence by the WHO and the CDC that COVID was not airborne. “FACT: #COVID19 is NOT airborne.” the WHO tweeted on March 28, 2020, accompanied by a large graphic (at right). Even at that time, there was plenty of evidence that COVID was airborne. So why was the WHO so insistent that it wasn’t?

Ironically, some of the resistance to airborne transmission can be traced back to a significant achievement in epidemiology. Namely, John Snow’s groundbreaking arguments that cholera was spread through water and food, not bad air (miasma). Snow’s theory took time to be accepted but when the story of germ theory’s eventual triumph came to be told, the bad air proponents were painted as outdated and ignorant. This sentiment was so pervasive among physicians and health officials that anyone suggesting airborne transmission of disease was vaguely suspect and tainted. Hence, the WHOs and CDCs readiness to label airborne transmission as dangerous, unscientific “misinformation” promulgated on social media (see the graphic). In reality, of course, the two theories were not at odds as one could easily accept that some germs were airborne. Indeed, there were experts in the physics of aerosols who said just that but these experts were siloed in departments of physics and engineering and not in medicine, epidemiology and public health.

As a result of this siloing, we lost time and lives by telling people that they were fine if they kept to the 6ft “rule” and washed their hands, when what we should have been telling them was open the windows, clean the air with UVC, and get outside. Windows not windex.

Linsey Marr at Virginia Tech was one of the aerosol experts who took a prominent role in publicly opposing the WHO guidance and making the case for aerosol transmission (Jose-Luis Jimenez was another important example). Thus, it’s nice to see that Marr is among this year’s MacArthur “genius” award winners. A good interview with Marr is here.

It didn’t take a genius to understand airborne transmission but it took courage to put one’s reputation on the line and go against what seemed like the scientific consensus. Marr’s award is thus an award to a scientist for speaking publicly in a time of crisis. I hope it encourages others, both to speak up when necessary but also to listen.

Addendum: I didn’t take part in the aerosol debates but my wife, who has done research in aerosols and germs, told me early on that “of course COVID is airborne!” Wisely, I chose to take the word of my wife over that of the WHO and CDC.

“Does Paid Sick Leave Facilitate Reproductive Choice?”

I might give the paper a slightly different title, but:

Unlike most advanced countries, the U.S. does not have a federal paid sick leave (PSL) policy; however, multiple states have adopted PSL mandates. PSL can facilitate healthcare use among women of child−bearing ages, including use of family planning services such as contraception, in−vitro fertilization, or abortion services. Use of these services, in turn, can increase or decrease birth rates. We combine administrative and survey data with difference-in-differences methods to shed light on these possibilities. Our findings indicate that state PSL mandates reduce birth rates, potentially through increased use of contraception but not changes in abortion services. We offer suggestive evidence of heterogeneity in birth rate effects by age, education, and race. Our findings imply that PSL policies may help women balance family and work responsibilities, and facilitate their reproductive choices.

That is a new NBER working paper by Johanna Catherine, Maclean, Ioana Popovici, and Christopher J. Ruhm.