Category: Medicine

Directed Innovation in the Artificial Limb Industry

Innovation responds to both demand and supply. New scientific discoveries can arise exogenously and lower the cost of some types of innovation. Innovation, however, also responds to demand. The patenting of new energy devices increases as the price of oil increases. Similarly, new pharmaceuticals to treat diseases of old age increase as the number of elderly increase.

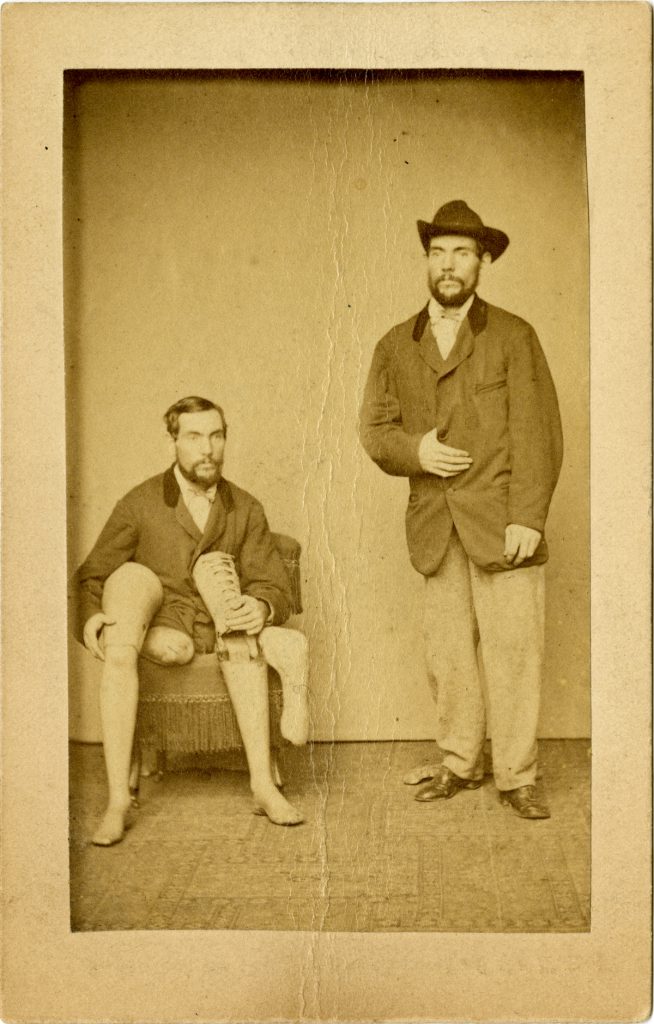

Similarly, the Civil War and World War I created a boom in the demand for artificial limbs and that in turn created a boom in innovation that led to better artificial limbs. The demand for new prosthetics was in some cases personal, as MacRae writes:

…the person who launched the era of modern prosthetics was also the first documented amputee of the Civil War–Confederate soldier James Edward Hanger. Hanger, who lost his leg above the knee to a cannon ball, was first fitted with a wooden peg leg by Yankee surgeons. Unhappy with the cumbersome appendage, Hanger eventually designed and built a new, lightweight leg from whittled barrel staves. Hanger’s innovative leg had hinges at the knee and foot, which helped him to sit more comfortably and to walk with a more natural gait. Hangar won the contract to make limbs for Confederate veterans. The company he founded–Hanger, Inc.–remains a key player in prosthetics and orthotics today.

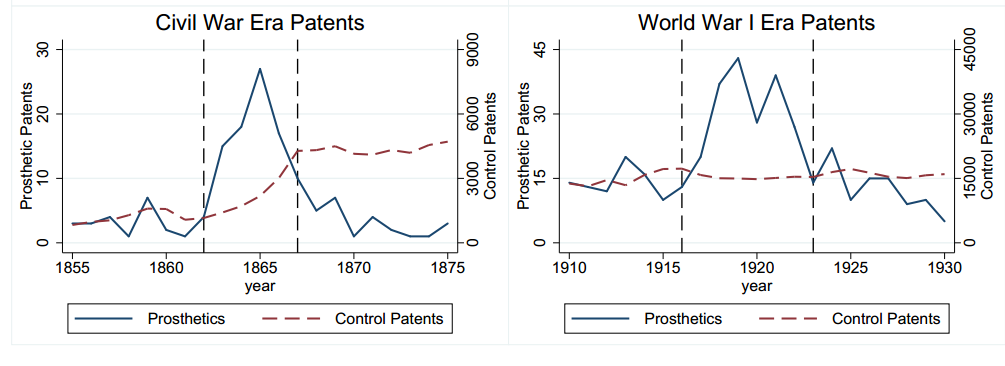

In a highly original paper, Jeffrey Clemens and Parker Rogers document the increase in patents during the war eras but they also show that the type of innovation not just the quantity also responded to economic incentives.

In the Civil War era, the quantity of limbs demanded increased but the government was quite stingy in paying for artificial limbs. As a result, innovators focused on process innovations that enabled the production of more limbs at lower cost. In contrast, WWI payments were more generous and the government emphasized reintegrated soldiers into society which made appearance a more dominant feature in limb patenting.

In the Civil War era, the quantity of limbs demanded increased but the government was quite stingy in paying for artificial limbs. As a result, innovators focused on process innovations that enabled the production of more limbs at lower cost. In contrast, WWI payments were more generous and the government emphasized reintegrated soldiers into society which made appearance a more dominant feature in limb patenting.

More generally, Clemens and Rogers show how the type of procurement contracts directs not just the quantity but the form of innovation. The lessons are relevant for modern health care costs. Many people, for example, have wondered why innovation tends to lower costs in most fields but raise costs in health care. Clemens and Rogers point to the nature of procurement contracts as a possible important influence.

Coronavirus markets in everything

Government officials across Hubei province, the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak, are desperate to find ways to stop the spread of the infection.

In Hubei’s Fangxian County, officials are trying a different approach — paying sick people.

According to an official Fangxian County notice, anyone who is sick and reports themselves to a hospital can expect to be paid.

Patients who have a fever and turn themselves in will receive 1,000 yuan ($142).

But officials and other interested parties are also being offered cash incentives if they catch anyone with a fever. For each person with a fever who is reported by an official or citizen, there is a reward of 500 yuan ($71).

The notice said that the offer is only valid from today until February 18.

Here is the link (nothing extra there, except a noisy video and you have to scroll down a lot). Via Neville.

Coronavirus multilateral insurance markets in everything

As financial markets fretted over the spread of a coronavirus outbreak in China this week, one security was in the firing line more directly than any other. Holders of the World Bank’s pandemic bond will lose principal if the disease spreads by a sufficient amount, writes Jasper Cox.

The World Bank’s pandemic bond, issued in 2017, provides funding for the development bank’s Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility (PEF) if an outbreak of one of six viruses meets certain conditions.

Here is the link (gated), here is a more detailed John Dizard FT story:

The event triggers were calculated on a complex formula based on deaths in the country of origin, a smaller number of deaths in neighbouring countries, and a relatively rapid increase in infection and mortality. Interest charges were assumed by rich-country donors including Germany and Japan. The riskier bonds pay 11.5 per cent over Libor, since they required only 250 deaths to reach the trigger. Not bad, considering the “expected loss” for the tranche was only 7.74 per cent. The less risky tranche required 2,500 deaths, so only paid 6.9 per cent over Libor, compared with an expected loss of 3.57 per cent.

Here is a pre-coronavirus discussion of the bonds, mostly with reference to Ebola.

Pollution in India and the World

I spoke on the negative effects of air pollution on health and GDP at Brookings India in Delhi. The talk was covered by Indian media. The Print had a good overview:

I spoke on the negative effects of air pollution on health and GDP at Brookings India in Delhi. The talk was covered by Indian media. The Print had a good overview:

The long-held belief that pollution is the cost a country has to pay for development is no longer true as bad air quality has a measurable detrimental impact on human productivity that could in turn reduce GDP, Canadian-American economist Alex Tabarrok said.

…“There is this old story that pollution is bad, but it increases GDP… When the United States and Japan were developing, they were polluted. So India and China also have to go through that stage of pollution — so that they get rich, and then they can afford to reduce pollution,” Tabarrok said.

“I want to say that that story is wrong. What I want to argue is that a lot of the new research indicates that we may be in a situation where we could be both healthier and wealthier at the same time by reducing pollution,” he said.

…At the seminar, Tabarrok pointed out that expecting people to make sacrifices for the sake of future generations is not a politically fruitful way to deal with pollution.

Citing the issue of crop burning in India, he said farmers are not going to be inclined to change their behaviour if they are told to stop stubble burning for the sake of Delhi residents.

“However, if these farmers are made aware of how the crop burning harms them and their families and affects their soil quality, they are more likely to participate in mitigation measures,” he said.

I was pretty tough on government policy as Business Today India reported:

More than half of India’s population lives in highly polluted areas. Research by Greenstone et al (2015) proves that 660 million people live in areas that exceed the Indian Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) for fine particulate pollution. In this context, having measures such as banning e-cigarettes and having odd-even days for vehicles to solve the problem of air pollution seems ridiculous, says Alex Tabarrok, Professor of Economics at the George Mason University and Research Fellow with the Mercatus Centre. “These are not appropriate solutions to the scale and the dimensions of the problem,” he says.

Cruise ship markets in everything

As the ongoing coronavirus epidemic disrupts cruise operations throughout Asia, Lindblad Expeditions, the cruise operator for National Geographic Expeditions, announced Thursday that it has become “the first self-disenfecting fleet in the cruise industry.”

The company has implemented a disinfectant coating solution developed by Danish company ACT.Global, which uses the photocatalytic properties of titanium dioxide to generate free radicals from airborne water molecules. When exposed to light, the coating converts airborne H20 into OH- ions, which break down bacteria, viruses, mold, airborne allergens and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). The coating can be applied to all surfaces to give them self-disinfecting qualities, including food-contact surfaces.

According to Lindblad, ACT.Global’s coating creates a cleaner, healthier ship while reducing impact on the environment. The antibacterial spray is transparent and odorless, and it purifies and deodorizes the air for up to one year.

Here is the full story, via Anecdotal.

U.S. nurse conservation fact of the day

In the period 2010–17 the number of NPs in the US more than doubled from approximately 91,000 to 190,000. This growth occurred in every US region and was driven by the rapid expansion of education programs that attracted nurses in the Millennial generation. Employment was concentrated in hospitals, physician offices, and outpatient care centers, and inflation-adjusted earnings grew by 5.5 percent over this period. The pronounced growth in the number of NPs has reduced the size of the registered nurse (RN) workforce by up to 80,000 nationwide.

Here is the underlying research, via the excellent Kevin Lewis. Given the growth of the health care sector, should not the number of nurses, broadly construed, be rising at a higher rate?

Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Model this asymmetric fatality rate?

The fatality rate in Wuhan is 4.1 percent and 2.8 percent in Hubei, compared to just 0.17 percent elsewhere in mainland China.

Is it really medical supply scarcity, as brought by the quarantine, as the NYT article seems to suggest? Why is the fatality rate so asymmetrically distributed, or is it?

Coronavirus would be worse without the web

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

Scientific information about the coronavirus has spread around the world remarkably quickly, mostly because of the internet. The virus has been identified, sequenced, and tracked online, and researchers around the world are working on possible fixes. The possibility that the failed ebola drug remdesivir may help protect against the virus is now well known and the drug is being deployed. The notion of using an HIV cocktail plus some anti-flu drugs against the coronavirus also has been publicized online. The final word on those potential fixes is not yet in, but the internet accelerates the spread of knowledge, along with its application.

Researchers from India prematurely published a claim that the coronavirus resembles in some critical ways the HIV virus, and their presentation hinted at the possibility something sinister was going on. The online scientific community leapt into action, however, and very quickly the theory was struck down and a retraction came almost immediately. I saw this whole process unfold on my Twitter feed in less than a day.

There is much more at the link, including a discussion of two possible downsides, first panic buying and second too much state-led “digital quarantine” of individuals. In addition, I wish to thank @pmarca and also Balaji Srinivasan for some ideas relevant to this column.

DIY Pancreas?

People suffering from diabetes have turned to sophisticated do-it-yourself technologies. Here’s the abstract to an excellent article on these developments by Crabtree, McLay and Wilmot:

Diabetes technology has been advancing rapidly over recent years. While some of this is driven by medical technology companies, a lot of the driving force for these developments comes from people living with diabetes (#WeAreNotWaiting) who have developed their own ‘do-it-yourself’ artificial pancreas systems (DIY APS) using continuous glucose monitoring, insulin pumps and smartphone technology to run algorithms shared freely with the intent of improving quality of life and glycaemic control. Existing evidence, although observational, seems promising but more robust data are required to establish the safety and outcomes. This is unregulated technology and the off-label use of interstitial glucose monitors and insulin pumps can be disconcerting for people living with diabetes, health care professionals, organisations, and diabetes technology companies alike.

Here we discuss the principles of DIY APS, the outcomes observed so far and the feedback from users, and debate the ethical issues which arise before looking to the future and newer technologies on the horizon.

Hat tip: Dennis Sheehan.

The long-run effects of cholera on an urban landscape

How do geographically concentrated income shocks influence the long-run spatial distribution of poverty within a city? We examine the impact on housing prices of a cholera epidemic in one neighborhood of nineteenth century London. Ten years after the epidemic, housing prices are significantly lower just inside the catchment area of the water pump that transmitted the disease. Moreover, differences in housing prices persist over the following 160 years. We make sense of these patterns by building a model of a rental market with frictions in which poor tenants exert a negative externality on their neighbors. This showcases how a locally concentrated income shock can persistently change the tenant composition of a block.

Here is the new AER piece by Attila Ambrus, Erica Field, and Robert Gonzalez. What might be the modern applications of this insight?

Why the coronavirus might boost Trump’s reelection prospects

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

The first and perhaps most important effect will be to make Trump’s nationalism seem ordinary, even understated. Hundreds of flights to China have already been canceled, countries are refusing to receive (or deciding to quarantine) Chinese nationals or visitors from China, and China itself is severely limiting travel within the country. Whether or not these prove effective measures, the idea of travel bans and restrictions no longer seems extreme or unconstitutional. Even if voters are confusing normal times with times of pandemic, on this issue Trump’s instincts now seem almost prescient.

When the flight of Americans returning from Wuhan was sent to Alaska last week instead of San Francisco, and subject to quarantine, very few political complaints were heard, including from leading Democrats. There might still be arguments about whether that was a justified violation of civil liberties, but the notion that a pandemic requires the federal government to take such measures, without a congressional vote, is not seriously contested.

That is going to help any incumbent president who believes in the strong exercise of executive power, as does Trump.

There is much more at the link.

Patents, Pollution, and Pot

In recent years, new research has significantly increased my belief that air pollution has substantial negative effects on productivity, IQ and health (see previous posts). Research in the field is exploding which means that there must also be more false positives. Consider two recent papers. The first, The Real Effect of Smoking Bans: Evidence from Corporate Innovation by Gao et al. finds that smoking prohibition increased patenting!

We identify a positive causal effect of healthy working environments on corporate innovation, using the staggered passage of U.S. state-level laws that ban smoking in workplaces. We find a significant increase in patents and patent citations for firms headquartered in states that have adopted such laws relative to firms headquartered in states without such laws. The increase is more pronounced for firms in states with stronger enforcement of such laws and in states with weaker preexisting tobacco controls. We present suggestive evidence that smoke-free laws affect innovation by improving inventor health and productivity and by attracting more productive inventors.

But the second, Do Firms Get High? The Impact of Marijuana Legalization on Firm Performance, Corporate Innovation, and Entrepreneurial Activity by Wang et al. finds that marijuana legalization increased patenting!

We find that state-level marijuana legalization has a positive financial impact on firms, likely by affecting firms’ human capital. Firms headquartered in marijuana-legalizing states receive higher market valuations, earn higher abnormal stock returns, improve employee productivity, and increase innovation. Exploiting firm level inventor data, we directly test the human capital channel and find that post legalization, firms retain inventors that become more productive and recruit more innovative talents from out of state. We also find that marijuana-legalizing states experience an increase in the number of new startups and venture capital investments.

Would anyone have been surprised if these two papers had shown exactly the opposite results? Indeed, there is some evidence that nicotine is solid cognitive enhancer and Tyler recently argued, on the basis of good evidence, that pot makes people dumb. Is it a coincidence that anti-cigarette and pro-pot papers appear as the country moves in this direction? Social desirability bias also applies to research. So no knock on either paper but I am unconvinced. As I like to say, trust literatures not papers.

Hat tip: The excellent Kevin Lewis.

The vaccine makers have solved for the equilibrium

GSK has made a corporate decision that while it wants to help in public health emergencies, it cannot continue to do so in the way it has in the past. Sanofi Pasteur has said its attempt to respond to Zika has served only to mar the company’s reputation. Merck has said while it is committed to getting its Ebola vaccine across the finish line it will not try to develop a vaccine that protects against other strains of Ebola and the related Marburg virus.

Drug makers “have very clearly articulated that … the current way of approaching this — to call them during an emergency and demand that they do this and that they reallocate resources, disrupt their daily operations in order to respond to these events — is completely unsustainable,” said Richard Hatchett, CEO of CEPI, an organization set up after the Ebola crisis to fund early-stage development of vaccines to protect against emerging disease threats.

Hatchett and others who plan for disease emergencies worry that, without the involvement of these types of companies, there will be no emergency response vaccines.

Here is more from Helen Branswell, you can follow her on Twitter here on the evolving coronavirus situation, she is maybe the single best follow on that topic?

Draining the swamp

From Jason Crawford, Emergent Ventures winner in Progress Studies:

…the surprising thing I found is that infectious disease mortality rates have been declining steadily since long before vaccines or antibiotics…

In 1900, the most deaths came from tuberculosis, influenza/pneumonia, and gastroenteric diseases such as dysentery. All of these were effectively conquered by antibiotics in the 1930s and ’40s, but were on the decline since at least the beginning of the century…

Indeed, digging further into the UK data from the late 1800s, we can see that TB was declining since at least 1850 and gastroenteric disease since the 1870s. And similar patterns hold for lesser killers such as measles, which didn’t have a vaccine until the 1960s, but which by then had already declined in mortality by more than 90% from its 1900 levels.

So what was going on? If you read my survey of technologies against infectious disease, you know that other than drugs and immunization, there is one other way to fight germs: cleaning up the environment.

I was surprised to learn that sanitation efforts began as early as the 1700s—and that these efforts were based on data collection and analysis, long before a full scientific theory of infection had been worked out.

There is much more at the link, including the footnotes for citations to the claims made here.

Do elections make you sick?

Yes basically, at least in Taiwan:

Anecdotal reports and small-scale studies suggest that elections are stressful, and might lead to a deterioration in voters’ mental well-being. Nonetheless, researchers have yet to establish whether elections actually make people sick, and if so, why. By applying a regression discontinuity design to administrative health care claims from Taiwan, we determine that elections increased health care use and expense only during legally specified campaign periods by as much as 19%. Overall, the treatment cost of illness caused by elections exceeded publicly reported levels of campaign expenditure, and accounted for 2% of total national health care costs during the campaign period.

That is from a new paper by Hung-Hao Chang and Chad Meyerhoefer.