Category: Medicine

Why have stock markets been falling so much?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, note first of all that the virus is a kind of referendum on global response capabilities, and so far we have been failing (with Singapore as a possible exception). Here is another bit:

…investors now have a better sense of what other investors think about risk. Before Covid-19, investors did not have much direct information about what other investors thought about the robustness of the global economy. Their expectations were not seriously being tested.

When a new shock to the system comes along, however, everyone gets to observe everyone else’s selling behavior. And investors have learned that the faith of their fellow investors is not as strong as they had thought. That raises the risk premium on holding stocks, and in turn causes share prices to fall more. Given how much this pandemic is a truly new event, and that the process of trading itself generates information about the forecasts of other investors, price volatility can be expected to continue.

And this:

The stock market is scared by the fact that it took so long for the stock market to be scared.

Developing…

Emergent Ventures winners, seventh cohort

Nicholas Whitaker of Brown, general career development grant in the area of Progress Studies.

Coleman Hughes, travel and career development grant.

Michael T. Foster, career development grant to study machine learning to predict which politicians will succeed and advance their careers.

Evan Horowitz, to start the Center for State Policy Analysis at Tufts, to impose greater rationality on policy discussions at the state level.

John Strider, a Progress Studies grant on how to reinvent the integrated corporate research lab.

Dryden Brown, to help build institutions and a financial center in Ghana, through his company Bluebook Cities.

Adaobi Adibe, to restructure credentialing, and build infrastructure for a more meritocratic world, helping workers create property rights in the evaluation of their own talent.

Shrirang Karandikar, and here (corrected link), to support an Indian project to get the kits to measure and understand local pollution.

Jassi Pannu, medical student at Stanford, to study best policy responses to pandemics.

Vasco Queirós, for his work on a Twitter browser app for superior threading and on-line communication.

My 2013 NYT column on pandemics

The government should resist the strong temptation to skimp on rewards. Many health care breakthroughs come through university research programs and government grants, but bringing an innovation to fruition and managing wide and rapid distribution usually requires the profit-seeking private sector. In any single instance, the government could save money by confiscating rights, but in the longer run this would discourage the search for additional remedies.

If anything, the American government — or, better yet, a consortium of governments — should pay more for pandemic remedies than what market-based auctions would yield. That’s because, if a major pandemic does arise, other countries may not respect intellectual property rights as they scramble to copy a drug or vaccine for domestic distribution. To encourage innovations, policy makers need to bolster the expectation of rewards.

I agree with the circulating critiques of current Trump administration policy, but the Democrats are no angels in this matter either. For instance:

Unfortunately, the United States lacks strong political coalitions for many beneficial public health measures. The Democratic Party has focused on insurance coverage and Medicaid expansion as political issues, while often wishing to lower prices of drugs or to weaken patent protection. The Obama administration’s new budget lowers spending on pharmaceuticals by an estimated $164 billion over 10 years, mostly through bargaining down Medicare drug prices. That makes it hard for the Democrats to embrace lucrative rewards for pharmaceutical companies or vaccine producers.

Here is the full column.

Coronavirus sentences to ponder

From a reader email:

I work at a large health care system on the west coast and the communication we have gotten from leadership is that we are only allowed to test for COVID-19 after discussion with and approval of the appropriate regulatory agencies.

How can this persist?

How the coronavirus is changing the culture of science and publication

A torrent of data is being released daily by preprint servers that didn’t even exist a decade ago, then dissected on platforms such as Slack and Twitter, and in the media, before formal peer review begins. Journal staffers are working overtime to get manuscripts reviewed, edited, and published at record speeds. The venerable New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) posted one COVID-19 paper within 48 hours of submission. Viral genomes posted on a platform named GISAID, more than 200 so far, are analyzed instantaneously by a phalanx of evolutionary biologists who share their phylogenetic trees in preprints and on social media.

“This is a very different experience from any outbreak that I’ve been a part of,” says epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The intense communication has catalyzed an unusual level of collaboration among scientists that, combined with scientific advances, has enabled research to move faster than during any previous outbreak. “An unprecedented amount of knowledge has been generated in 6 weeks,” says Jeremy Farrar, head of the Wellcome Trust…

The COVID-19 outbreak has broken that mold. Early this week, more than 283 papers had already appeared on preprint repositories (see graphic, below), compared with 261 published in journals. Two of the largest biomedical preprint servers, bioRxiv and medRxiv, “are currently getting around 10 papers each day on some aspect of the novel coronavirus,” says John Inglis, head of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, which runs both servers. The deluge “has been a challenge for our small teams … [they] are working evenings and weekends.”

Here is the full story, via Michael Nielsen.

The Advance Market Commitment

NBER: Ten years ago, donors committed $1.5 billion to a pilot Advance Market Commitment (AMC) to help purchase pneumococcal vaccine for low-income countries. The AMC aimed to encourage the development of such vaccines, ensure distribution to children in low-income countries, and pilot the AMC mechanism for possible future use. Three vaccines have been developed and more than 150 million children immunized, saving an estimated 700,000 lives. This paper reviews the economic logic behind AMCs, the experience with the pilot, and key issues for future AMCs.

That’s Kremer, Levin and Snyder. Definitely deserving of a Nobel and kudos to Bill and Melinda Gates for being early and major supporters.

All Praise the Fist Bump

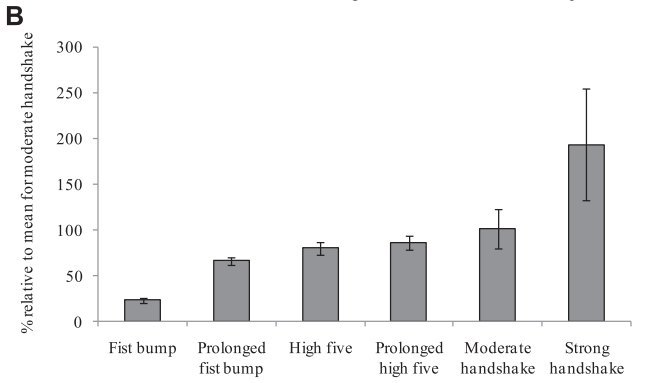

Handshaking spreads germs and is a bad method of greeting. I prefer an elegant namaste but that is slightly hard to coordinate on when the other person sticks out their hand. The fist bump is a little smoother and has a greater chance of being adopted.

A study by Mela and Whitsworth in the American Journal of Infection Control found that fist bumps transferred one-quarter as much bacteria as a moderate handshake and even less compared to a strong handshake. Fist bumps are better because of lower contact times and lower contact area.

Here’s Tom Hanks showing you how it’s done.

Hat tip: Bryan Caplan for always asking for the numbers.

That was then, this is now — pandemic response capabilities

Before adjourning last week, the US Senate passed and sent to President Bush a bill providing $3.8 billion for pandemic influenza preparedness and a controversial liability shield for those who produce and administer drugs and vaccines used in a declared public health emergency.

The preparedness funding and liability protection were part of the fiscal year 2006 defense spending bill passed by the Senate on the evening of Dec 21. The bill had cleared the House 2 days earlier.

The $3.8 billion for pandemic preparedness is a little more than half of the $7.1 billion Bush had requested in early November. House Republican leaders said last week the measure would fund roughly the fiscal year 2006 portion of Bush’s request.

As reported previously, the amount includes $350 million to improve state and local preparedness and directs the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to use most of the rest on “core preparedness activities,” including increasing vaccine production capacity, developing vaccines, and stockpiling antiviral drugs.

The liability provision offers broad legal protection for the makers of drugs, vaccines, and other medical “countermeasures” used when the HHS secretary declares an emergency. The provision says people claiming injury from a medical countermeasure can sue only if they prove “willful misconduct” by those who made or administered it. The bill calls for Congress to set up a compensation program for injuries, but it provides no funds for that purpose.

…But Sen. Edward Kennedy, D-Mass., and some other Democrats, along with consumer groups such as Public Citizen, derided the liability provision as a giveaway to the drug industry.

I am pleased to have argued for this in the time period leading up to this legislation, let us continue to hope we do not need it.

Why are we letting FDA regulations limit our number of coronavirus tests?

Since CDC and FDA haven’t authorized public health or hospital labs to run the [coronavirus] tests, right now #CDC is the only place that can. So, screening has to be rationed. Our ability to detect secondary spread among people not directly tied to China travel is greatly limited.

That is from Scott Gottlieb, former commissioner of the FDA, and also from Scott:

#FDA and #CDC can allow more labs to run the RT-PCR tests starting with public health agencies. Big medical centers can also be authorized to run tests under EUA. For now they’re not permitted to run the tests, even though many labs can do so reliably 9/9 cdc.gov/coronavirus/20

Here is further information about the obstacles facing the rollout of testing. And read here from a Harvard professor of epidemiology, and here. Clicking around and reading I have found this a difficult matter to get to the bottom of. Nonetheless no one disputes that America is not conducting many tests, and is not in a good position to scale up those tests rapidly, and some of those obstacles are regulatory. Why oh why are we messing around with this one?

For the pointer I thank Ada.

Health care economist sentences to ponder

Various ideas to cut costs in Medicare and Medicaid have been proposed in recent years. Health economists generally oppose those changes.

And this:

If health economists were in charge of the health system, not a lot would change, with some notable exceptions. Medicaid would not have work requirements (which would be unpopular among conservatives in some states), and taxes would go up for Medicare and for employer-based health insurance (which would make it unpopular among just about everybody).

Here is a much longer and excellent piece by Austin Frakt, surveying what health economists in the United States believe about health care policy. Also do note that health care economists overwhelmingly tend to be Democrats.

What should we think about all this? That we can trust these health care economists to (more or less) endorse the current system because it is in fact pretty good, relative to available constraints? That radical reforms, as suggested by say some Democratic presidential candidates, are undesirable and unneeded? That the Democratic economists who endorse single payer are way overreaching? Or that these health economists are both deluded — in whichever direction — and also major wusses?

Inquiring minds wish to know. Here is a related Twitter thread from Michael Cannon.

Random Critical Analysis on Health Care

The excellent Random Critical Analysis has a long blog post, really a short book, on why the conventional wisdom about health care, especially in the United States, is wrong. It’s a tour-de-force. Difficult to summarize but, as I see it, the key points are the following. (I also drawn on It’s still not the health care prices.)

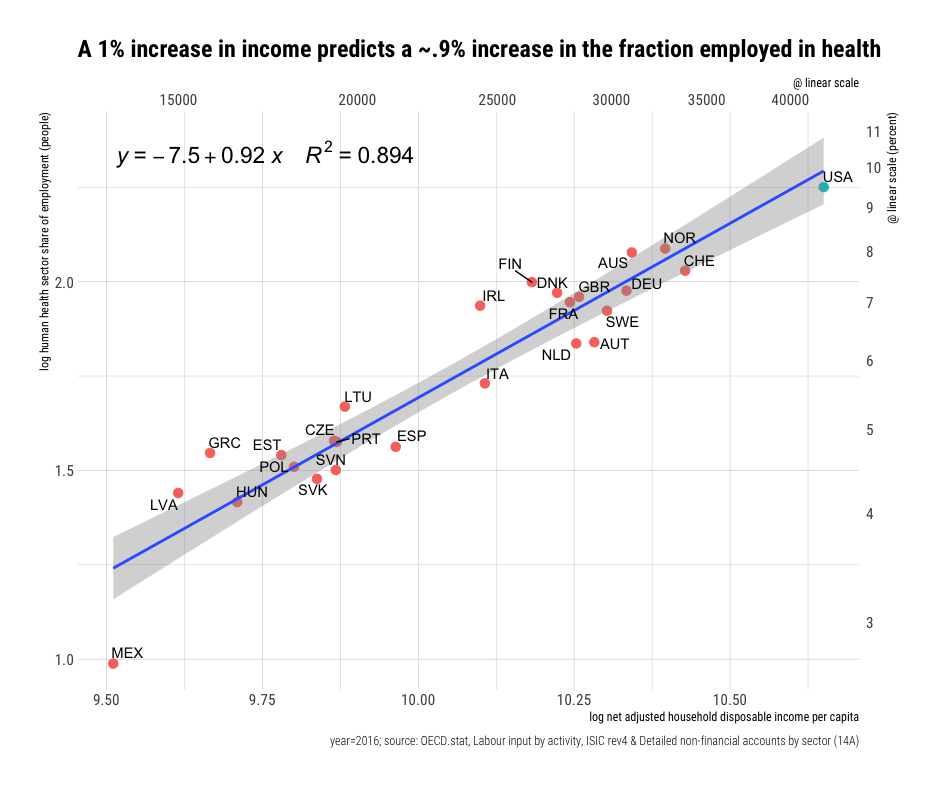

1. Health care spending is well predicted, indeed caused, by income.

Notice that the United States doesn’t look unusual when income is measured at the household level, i.e. Actual Individual Consumption, which measures the value of the bundle consumed by households whether the bundle items are bought in the market or provided by governments or non-profits. (AIC also avoids some issues with GDP per capita when a country has lots of intellectual property and exports, e.g. Ireland).

Notice that the United States doesn’t look unusual when income is measured at the household level, i.e. Actual Individual Consumption, which measures the value of the bundle consumed by households whether the bundle items are bought in the market or provided by governments or non-profits. (AIC also avoids some issues with GDP per capita when a country has lots of intellectual property and exports, e.g. Ireland).

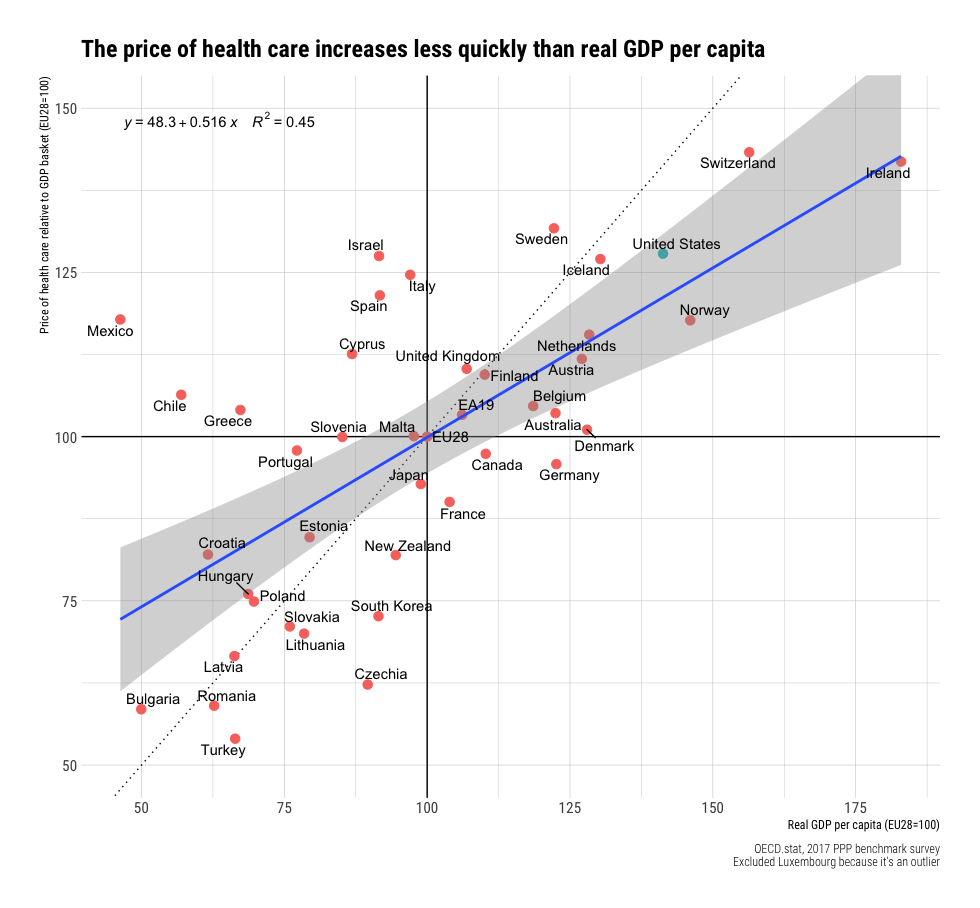

2. The price of health care increases with income but at a slower rate than income.

As a result of the above:

3. The price of health care relative to income is lower in rich countries, including the United States.

Let that sink in, health care prices are lower relative to income in richer countries. Health care in the United States is cheaper relative to income than in Greece, for example.

Since spending is going up faster than income but prices are not it must be the case that quantities are also increasing with income.

4. The density of health care workers (number of workers) and intensity (what the workers do) increases with income.

RCA: Rich countries consume much more cutting edge health care technology (innovations). For every 1% increase in real income, we find a 1-3% increase in organ transplant operations, a 1-2% increase in pacemaker and ICD implants, a 1-2% increase in the density of medical imaging/diagnostic technology, and likely similar patterns for all manner of other new technologies (e.g., insulin pumps, ADHD prescriptions, etc.). Obviously, these indicators are just the tip of the iceberg. Still, where data of this sort are available, they tend to be highly consistent with extreme income elasticity (particularly newer, more expensive forms of health care). In the main, costs rise because this technological change tends to requires a lot more people in hospitals and providers’ offices to deliver this increasingly complicated array of health care (surgical procedures, diagnostics, drugs, therapies, etc.).

A bottom line is that health care spending in the United States is not exceptional once we take US income into account.

RCA’s analysis is consistent with the Baumol effect and my analysis with Helland in Why Are the Prices So Damn High (we have some minor differences with RCA on physician incomes but neither of our analyses depend on that point). A big point is that RCA and Helland and I argue that the rising price sectors are not crowding out consumption of other goods. We can and are buying more of other goods even as we spend more on health care and education. Or, as RCA puts it:

…these trends indicate that the rising health share is robustly linked with a generally constant long-term increase in real consumption across essentially all other major consumption categories.

It is true that the United States has a convoluted payment system which results in absurd and enraging bills. Fixing the pricing system could generate more equity and efficiency but RCA’s analysis tells us that billions are at stake, not trillions. A corollary is that as other countries reach current US levels of income their health care spending will look more like the United States does today.

See RCA for much more.

Claims about Chennai naps

A three-week treatment providing information, encouragement, and sleep-related items increased sleep quantity by 27 minutes per night without improving sleep quality. Increased night sleep had no detectable effects on cognition, productivity, decision-making, or psychological and physical well-being, and led to small decreases in labor supply and thus earnings. In contrast, offering high-quality naps at the workplace increased productivity, cognition, psychological well-being, and patience.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Pedro Bessone, Gautam Rao, Frank Schilbach, heather Schofield, Mattie Toma.

Is the world fortunate that the coronavirus hit China first?

Is the world fortunate that the coronavirus hit China first? China’s government has totalitarian impulses but that–for the most part– is working to its favor in combating the virus. What other country in the world could quarantine a city of 11 million people on the basis of (at the time) 17 reported deaths?

CNN: Across China, 15 cities with a combined population of over 57 million people — more than the entire population of South Korea — have been placed under full or partial lockdown.

Wuhan itself has been effectively quarantined, with all routes in and out of the city closed or highly regulated. The government announced it is sending an additional 1,200 health workers — along with 135 People’s Liberation Army medical personnel — to help the city’s stretched hospital staff.

China’s response to the virus has been unprecedented and one cannot help but be a little bit impressed.

I was in India recently and if the coronavirus hits India it could spread very rapidly and millions could die not just in India but around the world. India does not have a strong public health system (it has invested instead in sickness treatment, another example of premature imitation), it also has plenty of other opportunistic diseases and bacteria which would magnify viral sickness and overwhelm the public health system, and India does not have a state strong enough to effectively lock down cities. India’s only big advantage versus China is that it’s relatively free press and communication system could make an outbreak more quickly spotted. China, in contrast, tried to hide the initial outbreak. This does, however, cut both ways. India’s 1994 outbreak of the plague quickly became news, which led to official action, but hundreds of thousands of people quickly left the epicenter in Surat–smart action at the time but deadly if those fleeing are infectious.

We need a Manhattan Project to research, develop and produce new vaccines at a faster pace; the US is best placed to be the world leader in this regard. On other actions, the United States stands somewhere in between China and India. US quarantine action would certainly be slower than in China but it could happen, probably through the military, as we are seeing now.

The US approach of slow but eventually decisive action is probably best but how slow is too slow? Right now most people assume that the coronavirus is a blow to China but if does create a serious pandemic then China may be the first to recover and stabilize.

Hat tip: Lunch discussions with Robin, John and Ajay.

Might the coronavirus bring freer speech to China?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

Chinese citizens are currently upset and panicked, and their online communication might exceed the ability of the censors to control it. Some censorship is done algorithmically, but much of it is performed by humans, if only because the algorithms are far from perfect and cannot pick up on the rapidly changing allusions and code words people use.

What happens if there are too many subversive messages to censor? The system might break down, and speech might become more free. Reimposing censorship might be difficult, politically and logistically.

There is yet another reason censorship might prove difficult. If you feel desperate and fear for your health, the penalties for speaking out online might not seem so bad by comparison. You might not care so much about that promotion at work or your standing in the party. Moreover, the stress of the situation may lower your inhibitions. And if public criticism becomes more common, it may seem safe to join the growing crowd. The eventual result of all this would be a partial collapse of censorship.

The link also considers the entirely possible scenario that Chinese liberties could instead decrease.

Utah sends employees to Mexico for lower prescription prices

Ann Lovell had never owned a passport before last year. Now, the 62-year-old teacher is a frequent flier, traveling every few months to Tijuana, Mexico, to buy medication for rheumatoid arthritis — with tickets paid for by the state of Utah’s public insurer.

Lovell is one of about 10 state workers participating in a year-old program to lower prescription drug costs by having public employees buy their medication in Mexico at a steep discount compared to U.S. prices. The program appears to be the first of its kind, and is a dramatic example of steps states are taking to alleviate the high cost of prescription drugs.

In one long, exhausting day, Lovell flies from Salt Lake City to San Diego. There, an escort picks her up and takes her across the border to a Tijuana hospital, where she gets a refill on her prescription. After that, she’s shuttled back to the airport and heads home.

Lovell had been paying $450 in co-pays every few months for her medication, though she said it would have increased to some $2,400 if she had not started traveling to Mexico. Without the program, she would not be able to afford the medicine she needs.

Here is the full story, via Jonathan Falk.