Category: Religion

Claims about atheists

The group that is most likely to contact a public official? Atheists.

The group that puts up political signs at the highest rates? Atheists.

HALF of atheists report giving to a candidate or campaign in the 2020 presidential election cycle.

And while they don’t lead the pack when it comes to attending a local political meeting, they only trail Hindus by four percentage points.

…atheists take part in plenty of political actions – 1.52 to be exact. The overall average in the entire sample was .91 activities. The average atheist is about 65% more politically engaged than the average American.

And this:

The results here are clear and unambiguous – atheists are more likely to engage in political activities at every level of education compared to Protestants, Catholics or Jews. For instance, an atheist with a high school diploma reports .7 activities, that’s at least .2 higher than any other religious group.

Political engagement is clearly related to education, though. The more educated one is, the more likely they are to be politically active. But at every step of the education scale, atheists lead the way. Sometimes those gaps are incredibly large. A college educated atheist engages in 1.7 activities, it’s only 1.05 activities for a college educated evangelical.

From Ryan Burge, here is the full data analysis.

My Conversation with the excellent Kevin Kelly

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the summary:

…Kevin and Tyler start this conversation on advice: what kinds of advice Kevin was afraid to give, his worst advice, how to get better at following advice, and whether people who ask for advice really want it in the first place. Then they move on to the best places to see traditional cultures in Asia, the one thing in Kevin’s travel kit he can’t be without, his favorite part of India, why he’s so excited about brain-computer interfaces, how AI will change religion, what the Amish can teach us about tech adoption, the most underrated documentary, his initial entry point into tech, why he’s impressed by the way Jeff Bezos handles power, the last thing he’s changed his mind about, how growing up in Westfield, New Jersey affected him, his next project called the Hundred Year Desirable Future, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Do you ever feel that if you don’t photograph a place, you haven’t really been there? Does it hold a different status? Like you haven’t organized the information; it’s just out on Pluto somewhere?

KELLY: Yes, I did. When I was younger, I had a religious conversion and I decided to ride my bicycle across the US. And part of that problem — part of the thing was that I was on my way to die, and I decided to leave my camera behind for this magnificent journey of a bicycle crossing the US. It was the most difficult thing I ever did, because I was just imagining all the magnificent pictures that I could take, that I wasn’t going to take. I took a sketchbook instead, and that appeased some of my desire to capture things visually.

But you’re absolutely right. It was a little bit of an addiction, where the framing of a photograph was how I saw the world. Still images: I was basically, in my head, clicking — I was clicking the shutter at the right moments when something would happen. That, I think, was not necessarily healthy — to be so dependent on that framing to enjoy the world.

I’ve learned to wean myself off from that necessity. Now I can travel with just a phone for the selfies that you might want to take.

COWEN: Maybe the earlier habit was better.

Recommended. And here is Kevin’s new book Excellent Advice: Wisdom I Wish I’d Known Earlier.

In Defense of Merit

An excellent paper co-authored by many luminaries, including two Nobel prize winners:

Merit is a central pillar of liberal epistemology, humanism, and democracy. The scientific enterprise, built on merit, has proven effective in generating scientific and technological advances, reducing suffering, narrowing social gaps, and improving the quality of life globally. This perspective documents the ongoing attempts to undermine the core principles of liberal epistemology and to replace merit with non-scientific, politically motivated criteria. We explain the philosophical origins of this conflict, document the intrusion of ideology into our scientific institutions, discuss the perils of abandoning merit, and offer an alternative, human-centered approach to address existing social inequalities.

Great work! The only problem? See where the paper was published (after being rejected elsewhere).

John Lennon and Yoko on Over Population

He was right.

Hat tip: Steven Hamilton who now likes the Beatles.

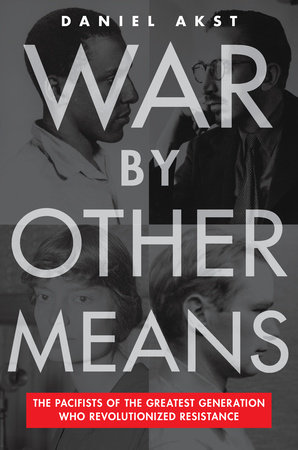

War by Other Means

In The Trial of The Chicago Seven, the Aaron Sorkin movie about the group of anti–Vietnam War protesters charged with inciting riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the focus is on the antics of Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen) and Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong). It’s a good movie but their story is not the only story. Among the Chicago Seven was an older, quieter, more bemused David Dellinger (played in the movie by John Carroll Lynch). It was not Dellinger’s first trial. In 1940 Dellinger had refused to register for the then-new draft, the first peacetime draft in America’s history, and he had been imprisoned as a conscientious objector and pro-pacifism protester. Dellinger served a year in federal prison in Danbury, CT, and upon his release, he adamantly refused to register once more. He was imprisoned for an additional two years in the maximum-security facility at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where he engaged in hunger strikes and endured periods of solitary confinement. Dellinger was the real deal.

In The Trial of The Chicago Seven, the Aaron Sorkin movie about the group of anti–Vietnam War protesters charged with inciting riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the focus is on the antics of Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen) and Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong). It’s a good movie but their story is not the only story. Among the Chicago Seven was an older, quieter, more bemused David Dellinger (played in the movie by John Carroll Lynch). It was not Dellinger’s first trial. In 1940 Dellinger had refused to register for the then-new draft, the first peacetime draft in America’s history, and he had been imprisoned as a conscientious objector and pro-pacifism protester. Dellinger served a year in federal prison in Danbury, CT, and upon his release, he adamantly refused to register once more. He was imprisoned for an additional two years in the maximum-security facility at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where he engaged in hunger strikes and endured periods of solitary confinement. Dellinger was the real deal.

In War by Other Means, Daniel Akst recaptures an older generation of anti-war, pro-pacifism protesters; people like Dellinger, the radical Catholic Dorothy Day, Bayard Rustin, Dwight MacDonald and others. This earlier group grew out of the disillusionment that many Americans felt after World War One–they resolved to never again be entangled in European death and destruction.

During the interwar period, moreover, the United States had developed perhaps the largest and best-organized pacifist movement in the world. Pacifism was part of the curriculum at some schools and firmly on the agenda of the mainline Protestant denominations that were such important institutions in the life of this churchgoing nation at the time….Pacifism was well established on campuses thanks to a massive and diverse national student anti-war movement….During the thirties pacifism, probably surpassed even the Depression as the dominant social issue in American liberal Protestantism…

It wasn’t just liberal Protestants, Pacifism also drew on the isolationist tradition:

…isolationism simply wanted to keep America out of other peoples’ bloody conflicts; it advocated strength through preparedness and put faith in the vastness of the oceans to keep us safe. “Isolationism” has become a dirty word since its heyday in the thirties, when it came into common usage. But in fact it started life as a pejorative, one used by American expansionists in the late nineteenth century to tar the righteous killjoys who objected to burgeoning US imperialism…

Regrettably, the unique blend of “left-wing” pacifism and “right-wing” isolationism, once prevalent in America, has largely vanished. Mostly vanished also is–for want of better terms–the Christian and left-wing libertarianism of people like Dellinger, Day and MacDonald, who although being on the left and hardly pro-market had a deep appreciation for individualism and civil society and a fear of the homogenizing and brutalizing role of the state.

Daniel Akst’s War by Other Means is an important and engaging look at a cast of remarkable American characters and their unique blend of ideological pacifism.

Addendum: Nick Gillespie at Reason has a very good interview with Akst.

My Conversation with Anna Keay

A very good episode, here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Tyler sat down with Anna to discuss the most plausible scenario where England could’ve remained a republic in the 17th century, what Robert Boyle learned from Sir William Petty, why some monarchs build palaces and other don’t, how renting from the Landmark Trust compares to Airbnb, how her job changes her views on wealth taxes, why neighborhood architecture has declined, how she’d handle the UK’s housing shortage, why giving back the Koh-i-Noor would cause more problems than it solves, why British houses have so little storage, the hardest part about living in an 800-year-old house, her favorite John Fowles book, why we should do more to preserve the Scottish Enlightenment, and more.

And here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Which are the old buildings that we have too many of in Britain? There’s a lot of Christopher Wren churches. I think there’s over 20.

KEAY: Too many?

COWEN: What if they were 15? They’re not all fantastic.

KEAY: They’re not all fantastic? Tell me one that isn’t fantastic.

COWEN: The Victorians knocked down St. Mildred. I’ve seen pictures of it. I don’t miss it.

KEAY: Well, you don’t miss something that’s not there. I think it’d be pretty hard to convince me that any Christopher Wren church wasn’t worth hanging on to. But your point is right, which is to say that not everything that was ever built is worth retaining. There are things which are clearly of much less interest or were poorly built, which are not serving a purpose anymore in a way that they need to. To me, it’s all about assessing what matters, what we care about.

It’s incredibly important to remember how you have to try and take the long view because if you let things go, you cannot later retrieve them. We look at the decisions that were made in the past about things that we really care about that were demolished — wonderful country houses, we’ve mentioned. It’s fantastic, for example, Euston Station, one of the great stations of the world, built in the middle of the 19th century, demolished in the ’60s, regretted forever since.

So, one of the things you have to be really careful about is to make a distinction between the fashion of the moment and things which we are going to regret, or our children or our grandchildren are going to curse us for having not valued or not thought about, not considered.

Which is why, in this country, we have this thing called the listing system, where there’s a process of identifying buildings which are important, and what’s called listing them — putting them on a list — which means that if you own them, you can’t change them without getting permission, which is a way of ensuring that things which you as an owner or I as an owner might not treat with scorn, that the interest of generations to come are represented in that.

COWEN: Why were so many big mistakes made in the middle part of the 20th century? St. Pancras almost was knocked down, as I’m sure you know. That would have been a huge blunder. There was something about that time that people seem to have become more interested in ugliness. Or what’s your theory? How do you explain the insanity that took all of Britain for, what, 30 years?

KEAY: Well, I think this is such a good question because this is, to me, what the study of history is all about, which is, you have to think about what it was like for that generation. You have to think of what it was like for people in the 1950s and ’60s, who had experienced, either firsthand or very close at hand, not just one but two catastrophic world wars in which numbers had been killed, places had been destroyed. The whole human cost of that time was so colossal, and the idea for that generation that something really fundamental had to change if we were going to be a society that wasn’t going to be killing one another at all time.

This has a real sort of mirror in the 17th century, during the Civil War in the 17th century. There’s a real feeling that something had to be done. Otherwise, God was going to strike down this nation, this errant nation. I think for that generation in the ’50s and ’60s, the sense that we simply have to do things differently because this pattern of life, this pattern of existence, this way we’ve operated as a society has been so destructive.

Although lots of things were done — when it comes to urban planning and so on — that we really regret now, I think you have to be really careful not to diminish the seriousness of intent of those people who were trying to conceive of what that world might be — more egalitarian, more democratic, involving more space, more air, more light, healthier — all these kinds of things.

Definitely recommended, with numerous interesting parts. And I am very happy to recommend Anna’s latest book The Restless Republic: Britain Without a Crown.

My Conversation with Jonathan GPT Swift

Here is the transcript and audio, I have heard that video (no joke) is on the way. Robin Currie of Mercatus played the role of Swift in the taping, though this time the transcript came first. Here is part of the summary:

GPT Swift discusses his support for the Church of Ireland, his shift from the Whigs to the Tories, and his opposition to William Wood’s copper coinage in Ireland. He also talks about his works, including Gulliver’s Travels and A Modest Proposal, and his skepticism of moral and intellectual progress. Swift addresses rumors about his relationship with Esther Johnson and his fascination with scatological themes in his works. He also discusses his early life in England, his intellectual mentor Sir William Temple, and his jovial attitude towards death.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Queen Anne: overrated or underrated? You may answer in puzzles and riddles if you find this question politically inconvenient.

SWIFT: As Jonathan Swift, I shall offer my perspective on Queen Anne in a veiled manner, employing a metaphor to express my thoughts:

Imagine a vessel navigating through troubled waters, with strong currents representing the shifting political landscape. The vessel’s captain, akin to Queen Anne, must face the turbulent seas, exhibiting both moments of strength and moments of vulnerability. Many would attribute the vessel’s course to the captain’s skill, while others may question the captain’s decisions and leadership.

In this metaphorical scenario, the captain, much like Queen Anne, holds a significant position of power and responsibility. However, the captain’s competence may be a subject of debate. Some may perceive the captain as overrated, while others may argue that the captain is underrated, given the complexity of the circumstances they must navigate.

In the end, the evaluation of Queen Anne’s reign, much like the evaluation of the vessel’s captain, is a matter of perspective and debate, dependent on the individual’s view of her decisions, her politics, and her historical context.

How about this for humor:

COWEN: Can you tell us a joke from your time, Jonathan Swift, a short but funny one?

SWIFT: I shall share a short jest that was popular during my time:

Why do we never tell secrets on a farm?

Because the potatoes have eyes and the corn has ears.

COWEN: So, what is a joke from your time that *you* would find funny?

SWIFT: My humor often leaned towards satire and irony. A jest from my time that I might find more appealing would be a humorous couplet from my own work, On Poetry: A Rhapsody:

“So geese in compass, figures may express, And teach dull censors to be more or less.”

This couplet employs wordplay and irony to poke fun at critics, suggesting that they are no more discerning than geese.

Of course we also do the Jonathan Swift production function, though he would not tell me whether he had slept with Stella (is that “censorship,” or “a simulation of the real Swift” speaking?). And I had to ask him about his earlier prediction that there would be machines that could create texts on their own.

As for method, here is TC:

Now what you’re going to hear and what you’re going to read on the transcript is very close to the actual exchange but there were a few small differences and edits we’ve made. Very often the GPT would begin the answer with, “As Jonathan Swift.” We simply took that out. Some of the longer answers, there were resummaries at the end. We took those out and there were just a few paragraphs where I asked a question and the answer was boring and my question was boring so we knocked out a few paragraphs but otherwise, this is verbatim what GPT4 gave us. I did not keep on repeating prompts trying to get the answer I wanted. This is really awfully close to the dialogue.

Do read the whole thing. It is too “textbook-y” in parts, but overall I was extremely impressed.

My excellent Conversation with Tom Holland

Here is the transcript, audio, and video. Here is part of the summary:

Historian Tom Holland joined Tyler to discuss in what ways his Christianity is influenced by Lord Byron, how the Book of Revelation precipitated a revolutionary tradition, which book of the Bible is most foundational for Western liberalism, the political differences between Paul and Jesus, why America is more pro-technology than Europe, why Herodotus is his favorite writer, why the Greeks and Persians didn’t industrialize despite having advanced technology, how he feels about devolution in the United Kingdom and the potential of Irish unification, what existential problem the Church of England faces, how the music of Ennio Morricone helps him write for a popular audience, why Jurassic Park is his favorite movie, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Which Gospel do you view as most foundational for Western liberalism and why?

HOLLAND: I think that that is a treacherous question to ask because it implies that there would be a coherent line of descent from any one text that can be traced like that. I think that the line of descent that leads from the Gospels and from the New Testament and from the Bible and, indeed, from the entire corpus of early Christian texts to modern liberalism is too confused, too much of a swirl of influences for us to trace it back to a particular text.

If I had to choose any one book from the Bible, it wouldn’t be a Gospel. It would probably be Paul’s Letter to the Galatians because Paul’s Letter to the Galatians contains the famous verse that there is no Jew or Greek, there is no slave or free, there is no man or woman in Christ. In a way, that text — even if you bracket out and remove the “in Christ” from it — that idea that, properly, there should be no discrimination between people of different cultural and ethnic backgrounds, based on gender, based on class, remains pretty foundational for liberalism to this day.

I think that liberalism, in so many ways, is a secularized rendering of that extraordinary verse. But I think it’s almost impossible to avoid metaphor when thinking about what the relationship is of these biblical texts, these biblical verses to the present day. I variously compared Paul, in particular in his letters and his writings, rather unoriginally, to an acorn from which a mighty oak grows.

But I think actually, more appropriately, of a depth charge released beneath the vast fabric of classical civilization. And the ripples, the reverberations of it are faint to begin with, and they become louder and louder and more and more disruptive. Those echoes from that depth charge continue to reverberate to this day.

And:

COWEN: In Genesis and Exodus, why does the older son so frequently catch it hard?

HOLLAND: Well, I’m an elder son.

COWEN: I know. Your brother’s younger, and he’s a historian.

HOLLAND: My brother is younger. It’s a question on which I’ve often pondered, because I was going to church.

COWEN: What do you expect from your brother?

HOLLAND: The truth is, I have no idea. I don’t know. I’ve often worried about it.

Quite a good CWT.

What should I ask Jonathan Swift?

Yes, I would like to do a Conversation with Jonathan “G.P.T.” Swift. Here is Wikipedia on Swift, excerpt:

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet, and Anglican cleric who became Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, hence his common sobriquet, “Dean Swift”.

Swift is remembered for works such as A Tale of a Tub (1704), An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity (1712), Gulliver’s Travels (1726), and A Modest Proposal (1729). He is regarded by the Encyclopædia Britannica as the foremost prose satirist in the English language.[1] He originally published all of his works under pseudonyms—such as Lemuel Gulliver, Isaac Bickerstaff, M. B. Drapier—or anonymously. He was a master of two styles of satire, the Horatian and Juvenalian styles.

His deadpan, ironic writing style, particularly in A Modest Proposal, has led to such satire being subsequently termed “Swiftian”.

So what should I ask him? I thank you in advance for your suggestions.

That was then, this is now

From Taylor C. Sherman’s useful Nehru’s India: A History in Seven Myths:

Although Hindu nationalists had gained prominence in the run-up to partition, the new Congress leaders of the Government of India tried to sideline them. After Gandhi’s assassination on 30 January 1948, members of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh were arrested, and the Hindu Mahasabha declared it would not take part in politics. In short, though raging before partition, the flames of Hindu chauvinism were quickly doused after independence, at least according to the old nationalist narrative. Secondly, the reform of Hinduism was seen as an essential element of secularism. To this end, a prominent Dalit, Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, was put in charge of both writing the Constitution and overseeing reform of Hindu personal law. Within a short time after independence, so the myth goes, India had a secular state, and was on course to establish a sense of security and belonging for the two groups who had raised the loudest objections to Congress’s nationalism: Muslims and Dalits.

As with so many of the myths that have arisen about this period after independence, the myth of India secularism owes a great deal to Jawaharlal Nehru.

The book is both a good focused view of the Nehru era, but excellent background for current disputes.

What should I ask David Bentley Hart?

I will be doing a Conversation with him. David Gordon claims the guy has read more than David Gordon! Here is Wikipedia:

David Bentley Hart (born 1965) is an American writer, philosopher, religious studies scholar, critic, and Orthodox theologian noted for his distinctive, humorous, pyrotechnic and often combative prose style. With academic works published on Christian metaphysics, philosophy of mind, classics, Asian languages, and literature, Hart received the Templeton Fellowship at the University of Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study in 2015 and organized a conference focused on the philosophy of mind. His translation of the New Testament was published by Yale in 2017 with a 2nd edition in 2023.

A prolific essayist, Hart has written on topics as diverse as art, baseball, literature, religion, philosophy, consciousness, problem of evil, apocatastasis, theosis, fairies, film, and politics. His fiction includes The Devil and Pierre Gernet: Stories (2012) as well as two books from 2021: Roland in Moonlight and Kenogaia (A Gnostic Tale). Hart also maintains a subscription newsletter called Leaves in the Wind that features original essays and conversations with other writers such as Rainn Wilson, China Miéville, Tariq Goddard, and Salley Vickers. Hart’s friendship and substantial intellectual common ground with John Milbank has been noted several times by both thinkers.

So what should I ask him?

Willingness to pay for upper-caste status

How much are individuals willing to pay for privileged status in a society with systemic discrimination? Utilizing unique data on indentured Indians in Fiji paying to return to India, I calculate how much upper-caste individuals were willing to pay historically for their status. I show the lower bound of the value of the uppermost castes in north India equaled almost 2.5 years’ gross wages. The ordering follows hypothesized inter-caste hierarchies and shows diminishing effects as caste status falls. Men entirely drive the effects. My results show some of the first evidence quantifying caste status values and speak to caste’s persistence.

Here is the paper by Alexander Persaud, with data from the turn of the 20th century, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

The Gift: An Analysis

Anna was excited to open her birthday present from her husband. He had been hinting at something special for weeks, and she couldn’t wait to see what it was. She tore off the wrapping paper and lifted the lid of the box. Inside was a beautiful necklace with a pendant shaped like a heart. It sparkled in the light and looked very expensive.

“Oh, honey, it’s gorgeous!” Anna exclaimed, hugging her husband. “Thank you so much! How did you afford this?”

He smiled and kissed her cheek. “Don’t worry about that. It’s your birthday, and you deserve the best. I love you.”

Anna put on the necklace and admired herself in the mirror. She felt like a princess. She decided to wear it to the party they were going to that night.

At the party, Anna received many compliments on her necklace. She felt proud and happy as she showed it off to her friends. She thanked her husband again for his wonderful gift.

Later that night, as they were driving home, Anna noticed that her husband seemed tense and nervous. He kept checking his phone and looking at the rearview mirror.

“Is everything okay?” she asked him.

He nodded quickly. “Yeah, yeah, everything’s fine.”

Anna shrugged and leaned back in her seat. She closed her eyes and smiled, thinking about how lucky she was.

Suddenly, she heard a loud bang and felt a jolt of pain in her chest. She opened her eyes and saw blood spilling from her necklace. The pendant had exploded.

She looked at her husband in horror. He had a gun in his hand and a cold expression on his face.

“I’m sorry, Anna,” he said calmly. “But I had no choice.”

He pulled the trigger again.

There are religious and spiritual undertones regarding temptation, sin, and mortality in this story. The pendant, the gift, represents the forbidden fruit of knowledge that leads to a fall from grace. The gift made Anna happy but also made her prideful and sinful. The sequence of Anna putting on the necklace, showing it off to other people, and then being killed with it can be seen as a metaphor for pride preceding a fall. The husband manipulates Anna by giving her such an extravagant gift before revealing his violent nature. This reflects how abusers often use a “cycle of abuse”, alternating between kindness and cruelty to reinforce control. The husband wants Anna to understand that she has done something terribly wrong even if she isn’t yet aware of what it is. The husband appears evil but the heart shaped pendant indicates a kind of true love. “I’m sorry,” he said calmly, “But I had no choice.”

Sadly, shortly after she wrote The Gift, the author was lobotomized. Perhaps she knew.

Hat tip: Jim Ward and also Claude for assistance in interpretation.

A new and possibly important paper

The title is the somewhat awkward: “A Macroscope of English Print Culture, 1530-1700, Applied to the Coevolution of Ideas on Religion, Science, and Institutions.” The abstract is informative:

We combine unsupervised machine-learning and econometric methods to examine cultural change in 16th- and 17th-century England. A machine-learning digest synthesizes the content of 57,863 texts comprising 83 million words into 110 topics. The topics include the expected, such as Natural Philosophy, and the unexpected, such as Baconian Theology. Using the data generated via machine-learning we then study facets of England’s cultural history. Timelines suggest that religious and political discourse gradually became more scholarly over time and economic topics more prominent. The epistemology associated with Bacon was present in theological debates already in the 16th century. Estimating a VAR, we explore the coevolution of ideas on religion, science, and institutions. Innovations in religious ideas induced strong responses in the other two domains. Revolutions did not spur debates on institutions nor did the founding of the Royal Society markedly elevate attention to science.

By Peter Grazjl and Peter Murrell, here is the paper itself. Via the excellent and ever-aware Kevin Lewis.

My Conversation with Glenn Loury

Moving throughout, here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the summary:

Economist and public intellectual Glenn Loury joined Tyler to discuss the soundtrack of Glenn’s life, Glenn’s early career in theoretical economics, his favorite Thomas Schelling story, the best place to raise a family in the US, the seeming worsening mental health issues among undergraduates, what he learned about himself while writing his memoir, what his right-wing fans most misunderstand about race, the key difference he has with John McWhorter, his evolving relationship with Christianity, the lasting influence of his late wife, his favorite novels and movies, how well he thinks he will face death, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: What’s your favorite Thomas Schelling story?

LOURY: [laughs] This is a story about me as much as it is about Tom Schelling. The year is 1984. I’ve been at Harvard for two years. I’m appointed a professor of economics and of Afro-American studies, and I’m having a crisis of confidence, thinking I’m never going to write another paper worth reading again.

Tom is a friend. He helped to recruit me because he was on the committee that Henry Rosovsky, the famous and powerful dean of the college of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard, who hired me — the committee that Rosovsky put together to try to find someone who could fill the position that I was hired into: professor of economics and of Afro-American Studies. They said Afro-American in those years.

Tom was my connection. He’s the guy who called me up when I was sitting at Michigan in Ann Arbor in early ’82, and said, “Do you think you might be interested in a job out here?” He had helped to recruit me.

So, I had this crisis of confidence. “Am I ever going to write another paper? I’m never going to write another paper.” I’m saying this to Tom, and he’s sitting, sober, listening, nodding, and suddenly starts laughing, and he can’t stop, and the laughing becomes uncontrollable. I am completely flummoxed by this. What the hell is he laughing at? What’s so funny? I just told him something I wouldn’t even tell my wife, which is, I was afraid I was a failure, that it was an imposter syndrome situation, that I could never measure up.

Everybody in the faculty meeting at Harvard’s economics department in 1982 was famous. Everybody. I was six years out of graduate school, and I didn’t know if I could fit in. He’s laughing, and I couldn’t get it. After a while, he regains his composure, and he says, “You think you’re the only one? This place is full of neurotics hiding behind their secretaries and their 10-foot oak doors, fearing the dreaded question, ‘What have you done for me lately?’ Why don’t you just put your head down and do your work? Believe me, everything will be okay.” That was Tom Schelling.

COWEN: He was great. I still miss him.

And the final question:

COWEN: Very last question. Do you think you will do a good job facing death?

Interesting and revealing throughout.