Category: Religion

Who first declared that God is dead?

According to Michael Sonenscher it was German romantic Jean Paul Richter:

I had gone through the midst of the worlds. I mounted unto the suns, and flew with the milky way across the wilderness of heaven; but there is no God. I plunged down as far as Being flings its shadow and pried into the abyss and cried, ‘Father, where art thou?’ But I heard only the everlasting tempest, which no-one sways. And the glittering rainbow of beings was hanging, without a sun that had formed it, over the abyss, and trickling down into it. And, when I looked up towards the limitless world for the eye of God, the world stared back at me with an empty bottomless eye socket; and Eternity was lying upon chaos, and gnawing it to pieces, and chewing the cud of what it had devoured. Scream on, ye discords! Scatter these shades with your screaming. For He is not!

That Richter is excerpt is from Sonenscher’s new and interesting book After Kant: The Romans, the Germans, and the Moderns in the History of Political Thought. One unique feature of Richter’s account is that Christ is the one bearing the news that God is dead. There are so many complainers about the Enlightenment these days, but how many go to the now-grossly underrated source of Richter?

*All Desire is a Desire for Being*

A new collection of essays by Rene Girard:

Edited by Cynthia L. Haven, self-recommending, buy it here.

Black Magic Technology

Arthur C. Clarke said that “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Here’s an example. You know those ubiquitous little LEDs on devices like speakers, card readers, microphones etc. that simply indicate that the device has power? The authors show that these LEDs can bleed information about power consumption that can be used to deduce when and for how long a computer is computing cryptographic keys and that can be used to deduce the keys. For example, using a “hijacked” security camera the author’s were able to film the power LED on a smart card reader from 16 meters away and from that able to deduce the keys. Paper here. Video below.

Now some people will say, well all you have to do is make sure the LEDs are properly insulated from the main power and adjust the cryptographic algorithms to not take some shortcuts and your systems will be safe. Uh huh.

Eliezer Yudkowsky has a more realistic perspective. Although this is not about AI per se, he notes this is a good example of the kind of thing that a superintelligence could do that would not have been predicted in advance and would seem to require magical powers.

Orwell’s Falsified Prediction on Empire

In The Road to Wigan Pier, George Orwell argued:

…the high standard of life we enjoy in England depends upon our keeping a tight hold on the Empire, particularly the tropical portions of it such as India and Africa. Under the capitalist system, in order that England may live in comparative comfort, a hundred million Indians must live on the verge of starvation–an evil state of affairs, but you acquiesce in it every time you step into a taxi or eat a plate of strawberries and cream. The alternative is to throw the Empire overboard and reduce England to a cold and unimportant little island where we should all have to work very hard and live mainly on herrings and potatoes.

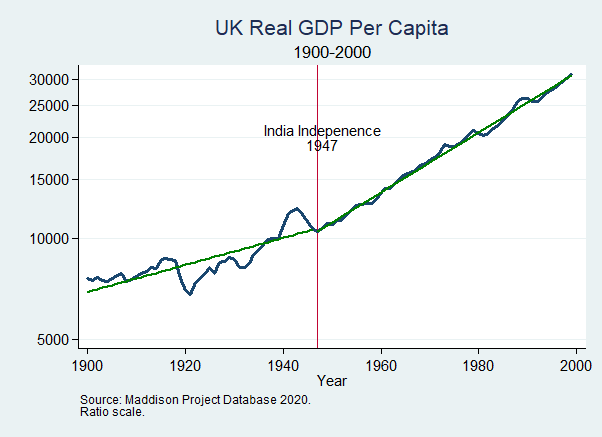

Wigan Pier was published in 1937 and a scant ten years later, India gained its independence. Thus, we have a clear prediction. Was England reduced to living mainly on herrings and potatoes after Indian Independence? No. In fact, not only did the UK continue to get rich after the end of empire, the growth rate of GDP increased.

Orwell’s failed prediction stemmed from two reasons. First, he was imbued with zero-sum thinking. It should have been obvious that India was not necessary to the high standard of living enjoyed in England because most of that high standard of living came from increases in the productivity of labor brought about by capitalism and the industrial revolution and most of that was independent of empire (Most. Maybe all. Maybe more than all. Maybe not all. One can debate the finer details on financing but of that debate I have little interest.) The second, related reason was that Orwell had a deep suspicion and distaste for technology, a theme I will take up in a later post.

Orwell, who was born in India and learned something about despotism as a police officer in Burma, opposed empire. Thus, his argument that we had to be poor to be just was a tragic dilemma, one of many that made him pessimistic about the future of humanity.

Islam and human capital in historical Spain

We use a unique dataset on Muslim domination between 711-1492 and literacy in 1860 for about 7500 municipalities to study the long-run impact of Islam on human-capital in historical Spain. Reduced-form estimates show a large and robust negative relationship between length of Muslim rule and literacy. We argue that, contrary to local arrangements set up by Christians, Islamic institutions discouraged the rise of the merchant class, blocking local forms of self-government and thereby persistently hindering demand for education. Indeed, results show that a longer Muslim domination in Spain is negatively related to the share of merchants, whereas neither later episodes of trade nor differences in jurisdictions and different stages of the Reconquista affect our main results. Consistent with our interpretation, panel estimates show that cities under Muslim rule missed-out on the critical juncture to establish self-government institutions.

That is from a new paper by Francesco Cinnirella, Alieza Naghavi, and Giovanni Prarolo, via a loyal MR reader.

*The Fall of the Turkish Model*

The author is Cihan Tuğal, and the subtitle is How the Arab Uprisings Brought Down Islamic Liberalism, though the book is more concretely a comparison across Egypt and Tunisia as well, with frequent remarks on Iran. Here is one excerpt:

This led to what Kevan Harris has called the ‘subcontractor state’: an economy which is neither centralized under a governmental authority not privatized and liberalized. The subcontractor state has decentralized its social and economic roles without liberalizing the economy or even straightforwardly privatizing the state-owned enterprises. As a result, the peculiar third sector of the Iranian economy has expanded in rather complicated and unpredictable ways. Rather than leading to liberalization privatization under revolutionary corporatism intensified and twisted the significance of organization such as the bonyads…Privatization under the populist-conservative Ahmedinejad exploited the ambiguities of the tripartite division of the economy…’Privatization’ entailed the sale of public assets not to private companies but to nongovernmental public enterprises (such as pension funds, the bonyads and military contractors).

This book is one useful background source for the current electoral process in Turkey.

Claims about atheists

The group that is most likely to contact a public official? Atheists.

The group that puts up political signs at the highest rates? Atheists.

HALF of atheists report giving to a candidate or campaign in the 2020 presidential election cycle.

And while they don’t lead the pack when it comes to attending a local political meeting, they only trail Hindus by four percentage points.

…atheists take part in plenty of political actions – 1.52 to be exact. The overall average in the entire sample was .91 activities. The average atheist is about 65% more politically engaged than the average American.

And this:

The results here are clear and unambiguous – atheists are more likely to engage in political activities at every level of education compared to Protestants, Catholics or Jews. For instance, an atheist with a high school diploma reports .7 activities, that’s at least .2 higher than any other religious group.

Political engagement is clearly related to education, though. The more educated one is, the more likely they are to be politically active. But at every step of the education scale, atheists lead the way. Sometimes those gaps are incredibly large. A college educated atheist engages in 1.7 activities, it’s only 1.05 activities for a college educated evangelical.

From Ryan Burge, here is the full data analysis.

My Conversation with the excellent Kevin Kelly

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the summary:

…Kevin and Tyler start this conversation on advice: what kinds of advice Kevin was afraid to give, his worst advice, how to get better at following advice, and whether people who ask for advice really want it in the first place. Then they move on to the best places to see traditional cultures in Asia, the one thing in Kevin’s travel kit he can’t be without, his favorite part of India, why he’s so excited about brain-computer interfaces, how AI will change religion, what the Amish can teach us about tech adoption, the most underrated documentary, his initial entry point into tech, why he’s impressed by the way Jeff Bezos handles power, the last thing he’s changed his mind about, how growing up in Westfield, New Jersey affected him, his next project called the Hundred Year Desirable Future, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Do you ever feel that if you don’t photograph a place, you haven’t really been there? Does it hold a different status? Like you haven’t organized the information; it’s just out on Pluto somewhere?

KELLY: Yes, I did. When I was younger, I had a religious conversion and I decided to ride my bicycle across the US. And part of that problem — part of the thing was that I was on my way to die, and I decided to leave my camera behind for this magnificent journey of a bicycle crossing the US. It was the most difficult thing I ever did, because I was just imagining all the magnificent pictures that I could take, that I wasn’t going to take. I took a sketchbook instead, and that appeased some of my desire to capture things visually.

But you’re absolutely right. It was a little bit of an addiction, where the framing of a photograph was how I saw the world. Still images: I was basically, in my head, clicking — I was clicking the shutter at the right moments when something would happen. That, I think, was not necessarily healthy — to be so dependent on that framing to enjoy the world.

I’ve learned to wean myself off from that necessity. Now I can travel with just a phone for the selfies that you might want to take.

COWEN: Maybe the earlier habit was better.

Recommended. And here is Kevin’s new book Excellent Advice: Wisdom I Wish I’d Known Earlier.

In Defense of Merit

An excellent paper co-authored by many luminaries, including two Nobel prize winners:

Merit is a central pillar of liberal epistemology, humanism, and democracy. The scientific enterprise, built on merit, has proven effective in generating scientific and technological advances, reducing suffering, narrowing social gaps, and improving the quality of life globally. This perspective documents the ongoing attempts to undermine the core principles of liberal epistemology and to replace merit with non-scientific, politically motivated criteria. We explain the philosophical origins of this conflict, document the intrusion of ideology into our scientific institutions, discuss the perils of abandoning merit, and offer an alternative, human-centered approach to address existing social inequalities.

Great work! The only problem? See where the paper was published (after being rejected elsewhere).

John Lennon and Yoko on Over Population

He was right.

Hat tip: Steven Hamilton who now likes the Beatles.

War by Other Means

In The Trial of The Chicago Seven, the Aaron Sorkin movie about the group of anti–Vietnam War protesters charged with inciting riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the focus is on the antics of Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen) and Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong). It’s a good movie but their story is not the only story. Among the Chicago Seven was an older, quieter, more bemused David Dellinger (played in the movie by John Carroll Lynch). It was not Dellinger’s first trial. In 1940 Dellinger had refused to register for the then-new draft, the first peacetime draft in America’s history, and he had been imprisoned as a conscientious objector and pro-pacifism protester. Dellinger served a year in federal prison in Danbury, CT, and upon his release, he adamantly refused to register once more. He was imprisoned for an additional two years in the maximum-security facility at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where he engaged in hunger strikes and endured periods of solitary confinement. Dellinger was the real deal.

In The Trial of The Chicago Seven, the Aaron Sorkin movie about the group of anti–Vietnam War protesters charged with inciting riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the focus is on the antics of Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen) and Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong). It’s a good movie but their story is not the only story. Among the Chicago Seven was an older, quieter, more bemused David Dellinger (played in the movie by John Carroll Lynch). It was not Dellinger’s first trial. In 1940 Dellinger had refused to register for the then-new draft, the first peacetime draft in America’s history, and he had been imprisoned as a conscientious objector and pro-pacifism protester. Dellinger served a year in federal prison in Danbury, CT, and upon his release, he adamantly refused to register once more. He was imprisoned for an additional two years in the maximum-security facility at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where he engaged in hunger strikes and endured periods of solitary confinement. Dellinger was the real deal.

In War by Other Means, Daniel Akst recaptures an older generation of anti-war, pro-pacifism protesters; people like Dellinger, the radical Catholic Dorothy Day, Bayard Rustin, Dwight MacDonald and others. This earlier group grew out of the disillusionment that many Americans felt after World War One–they resolved to never again be entangled in European death and destruction.

During the interwar period, moreover, the United States had developed perhaps the largest and best-organized pacifist movement in the world. Pacifism was part of the curriculum at some schools and firmly on the agenda of the mainline Protestant denominations that were such important institutions in the life of this churchgoing nation at the time….Pacifism was well established on campuses thanks to a massive and diverse national student anti-war movement….During the thirties pacifism, probably surpassed even the Depression as the dominant social issue in American liberal Protestantism…

It wasn’t just liberal Protestants, Pacifism also drew on the isolationist tradition:

…isolationism simply wanted to keep America out of other peoples’ bloody conflicts; it advocated strength through preparedness and put faith in the vastness of the oceans to keep us safe. “Isolationism” has become a dirty word since its heyday in the thirties, when it came into common usage. But in fact it started life as a pejorative, one used by American expansionists in the late nineteenth century to tar the righteous killjoys who objected to burgeoning US imperialism…

Regrettably, the unique blend of “left-wing” pacifism and “right-wing” isolationism, once prevalent in America, has largely vanished. Mostly vanished also is–for want of better terms–the Christian and left-wing libertarianism of people like Dellinger, Day and MacDonald, who although being on the left and hardly pro-market had a deep appreciation for individualism and civil society and a fear of the homogenizing and brutalizing role of the state.

Daniel Akst’s War by Other Means is an important and engaging look at a cast of remarkable American characters and their unique blend of ideological pacifism.

Addendum: Nick Gillespie at Reason has a very good interview with Akst.

My Conversation with Anna Keay

A very good episode, here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Tyler sat down with Anna to discuss the most plausible scenario where England could’ve remained a republic in the 17th century, what Robert Boyle learned from Sir William Petty, why some monarchs build palaces and other don’t, how renting from the Landmark Trust compares to Airbnb, how her job changes her views on wealth taxes, why neighborhood architecture has declined, how she’d handle the UK’s housing shortage, why giving back the Koh-i-Noor would cause more problems than it solves, why British houses have so little storage, the hardest part about living in an 800-year-old house, her favorite John Fowles book, why we should do more to preserve the Scottish Enlightenment, and more.

And here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Which are the old buildings that we have too many of in Britain? There’s a lot of Christopher Wren churches. I think there’s over 20.

KEAY: Too many?

COWEN: What if they were 15? They’re not all fantastic.

KEAY: They’re not all fantastic? Tell me one that isn’t fantastic.

COWEN: The Victorians knocked down St. Mildred. I’ve seen pictures of it. I don’t miss it.

KEAY: Well, you don’t miss something that’s not there. I think it’d be pretty hard to convince me that any Christopher Wren church wasn’t worth hanging on to. But your point is right, which is to say that not everything that was ever built is worth retaining. There are things which are clearly of much less interest or were poorly built, which are not serving a purpose anymore in a way that they need to. To me, it’s all about assessing what matters, what we care about.

It’s incredibly important to remember how you have to try and take the long view because if you let things go, you cannot later retrieve them. We look at the decisions that were made in the past about things that we really care about that were demolished — wonderful country houses, we’ve mentioned. It’s fantastic, for example, Euston Station, one of the great stations of the world, built in the middle of the 19th century, demolished in the ’60s, regretted forever since.

So, one of the things you have to be really careful about is to make a distinction between the fashion of the moment and things which we are going to regret, or our children or our grandchildren are going to curse us for having not valued or not thought about, not considered.

Which is why, in this country, we have this thing called the listing system, where there’s a process of identifying buildings which are important, and what’s called listing them — putting them on a list — which means that if you own them, you can’t change them without getting permission, which is a way of ensuring that things which you as an owner or I as an owner might not treat with scorn, that the interest of generations to come are represented in that.

COWEN: Why were so many big mistakes made in the middle part of the 20th century? St. Pancras almost was knocked down, as I’m sure you know. That would have been a huge blunder. There was something about that time that people seem to have become more interested in ugliness. Or what’s your theory? How do you explain the insanity that took all of Britain for, what, 30 years?

KEAY: Well, I think this is such a good question because this is, to me, what the study of history is all about, which is, you have to think about what it was like for that generation. You have to think of what it was like for people in the 1950s and ’60s, who had experienced, either firsthand or very close at hand, not just one but two catastrophic world wars in which numbers had been killed, places had been destroyed. The whole human cost of that time was so colossal, and the idea for that generation that something really fundamental had to change if we were going to be a society that wasn’t going to be killing one another at all time.

This has a real sort of mirror in the 17th century, during the Civil War in the 17th century. There’s a real feeling that something had to be done. Otherwise, God was going to strike down this nation, this errant nation. I think for that generation in the ’50s and ’60s, the sense that we simply have to do things differently because this pattern of life, this pattern of existence, this way we’ve operated as a society has been so destructive.

Although lots of things were done — when it comes to urban planning and so on — that we really regret now, I think you have to be really careful not to diminish the seriousness of intent of those people who were trying to conceive of what that world might be — more egalitarian, more democratic, involving more space, more air, more light, healthier — all these kinds of things.

Definitely recommended, with numerous interesting parts. And I am very happy to recommend Anna’s latest book The Restless Republic: Britain Without a Crown.

My Conversation with Jonathan GPT Swift

Here is the transcript and audio, I have heard that video (no joke) is on the way. Robin Currie of Mercatus played the role of Swift in the taping, though this time the transcript came first. Here is part of the summary:

GPT Swift discusses his support for the Church of Ireland, his shift from the Whigs to the Tories, and his opposition to William Wood’s copper coinage in Ireland. He also talks about his works, including Gulliver’s Travels and A Modest Proposal, and his skepticism of moral and intellectual progress. Swift addresses rumors about his relationship with Esther Johnson and his fascination with scatological themes in his works. He also discusses his early life in England, his intellectual mentor Sir William Temple, and his jovial attitude towards death.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Queen Anne: overrated or underrated? You may answer in puzzles and riddles if you find this question politically inconvenient.

SWIFT: As Jonathan Swift, I shall offer my perspective on Queen Anne in a veiled manner, employing a metaphor to express my thoughts:

Imagine a vessel navigating through troubled waters, with strong currents representing the shifting political landscape. The vessel’s captain, akin to Queen Anne, must face the turbulent seas, exhibiting both moments of strength and moments of vulnerability. Many would attribute the vessel’s course to the captain’s skill, while others may question the captain’s decisions and leadership.

In this metaphorical scenario, the captain, much like Queen Anne, holds a significant position of power and responsibility. However, the captain’s competence may be a subject of debate. Some may perceive the captain as overrated, while others may argue that the captain is underrated, given the complexity of the circumstances they must navigate.

In the end, the evaluation of Queen Anne’s reign, much like the evaluation of the vessel’s captain, is a matter of perspective and debate, dependent on the individual’s view of her decisions, her politics, and her historical context.

How about this for humor:

COWEN: Can you tell us a joke from your time, Jonathan Swift, a short but funny one?

SWIFT: I shall share a short jest that was popular during my time:

Why do we never tell secrets on a farm?

Because the potatoes have eyes and the corn has ears.

COWEN: So, what is a joke from your time that *you* would find funny?

SWIFT: My humor often leaned towards satire and irony. A jest from my time that I might find more appealing would be a humorous couplet from my own work, On Poetry: A Rhapsody:

“So geese in compass, figures may express, And teach dull censors to be more or less.”

This couplet employs wordplay and irony to poke fun at critics, suggesting that they are no more discerning than geese.

Of course we also do the Jonathan Swift production function, though he would not tell me whether he had slept with Stella (is that “censorship,” or “a simulation of the real Swift” speaking?). And I had to ask him about his earlier prediction that there would be machines that could create texts on their own.

As for method, here is TC:

Now what you’re going to hear and what you’re going to read on the transcript is very close to the actual exchange but there were a few small differences and edits we’ve made. Very often the GPT would begin the answer with, “As Jonathan Swift.” We simply took that out. Some of the longer answers, there were resummaries at the end. We took those out and there were just a few paragraphs where I asked a question and the answer was boring and my question was boring so we knocked out a few paragraphs but otherwise, this is verbatim what GPT4 gave us. I did not keep on repeating prompts trying to get the answer I wanted. This is really awfully close to the dialogue.

Do read the whole thing. It is too “textbook-y” in parts, but overall I was extremely impressed.

My excellent Conversation with Tom Holland

Here is the transcript, audio, and video. Here is part of the summary:

Historian Tom Holland joined Tyler to discuss in what ways his Christianity is influenced by Lord Byron, how the Book of Revelation precipitated a revolutionary tradition, which book of the Bible is most foundational for Western liberalism, the political differences between Paul and Jesus, why America is more pro-technology than Europe, why Herodotus is his favorite writer, why the Greeks and Persians didn’t industrialize despite having advanced technology, how he feels about devolution in the United Kingdom and the potential of Irish unification, what existential problem the Church of England faces, how the music of Ennio Morricone helps him write for a popular audience, why Jurassic Park is his favorite movie, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Which Gospel do you view as most foundational for Western liberalism and why?

HOLLAND: I think that that is a treacherous question to ask because it implies that there would be a coherent line of descent from any one text that can be traced like that. I think that the line of descent that leads from the Gospels and from the New Testament and from the Bible and, indeed, from the entire corpus of early Christian texts to modern liberalism is too confused, too much of a swirl of influences for us to trace it back to a particular text.

If I had to choose any one book from the Bible, it wouldn’t be a Gospel. It would probably be Paul’s Letter to the Galatians because Paul’s Letter to the Galatians contains the famous verse that there is no Jew or Greek, there is no slave or free, there is no man or woman in Christ. In a way, that text — even if you bracket out and remove the “in Christ” from it — that idea that, properly, there should be no discrimination between people of different cultural and ethnic backgrounds, based on gender, based on class, remains pretty foundational for liberalism to this day.

I think that liberalism, in so many ways, is a secularized rendering of that extraordinary verse. But I think it’s almost impossible to avoid metaphor when thinking about what the relationship is of these biblical texts, these biblical verses to the present day. I variously compared Paul, in particular in his letters and his writings, rather unoriginally, to an acorn from which a mighty oak grows.

But I think actually, more appropriately, of a depth charge released beneath the vast fabric of classical civilization. And the ripples, the reverberations of it are faint to begin with, and they become louder and louder and more and more disruptive. Those echoes from that depth charge continue to reverberate to this day.

And:

COWEN: In Genesis and Exodus, why does the older son so frequently catch it hard?

HOLLAND: Well, I’m an elder son.

COWEN: I know. Your brother’s younger, and he’s a historian.

HOLLAND: My brother is younger. It’s a question on which I’ve often pondered, because I was going to church.

COWEN: What do you expect from your brother?

HOLLAND: The truth is, I have no idea. I don’t know. I’ve often worried about it.

Quite a good CWT.

What should I ask Jonathan Swift?

Yes, I would like to do a Conversation with Jonathan “G.P.T.” Swift. Here is Wikipedia on Swift, excerpt:

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet, and Anglican cleric who became Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, hence his common sobriquet, “Dean Swift”.

Swift is remembered for works such as A Tale of a Tub (1704), An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity (1712), Gulliver’s Travels (1726), and A Modest Proposal (1729). He is regarded by the Encyclopædia Britannica as the foremost prose satirist in the English language.[1] He originally published all of his works under pseudonyms—such as Lemuel Gulliver, Isaac Bickerstaff, M. B. Drapier—or anonymously. He was a master of two styles of satire, the Horatian and Juvenalian styles.

His deadpan, ironic writing style, particularly in A Modest Proposal, has led to such satire being subsequently termed “Swiftian”.

So what should I ask him? I thank you in advance for your suggestions.