Category: The Arts

What should I ask Daniel Gross?

I will be doing a Conversation with him, noting that he is my co-author on Talent: How to Identify Energizers, Creators, and Winners Around the World.

Daniel is an entrepreneur and venture capitalist and here is his Wikipedia page. Here is Daniel on Twitter. Here is Daniel’s ideas page. Here is Daniel on his work, including Pioneer.

Since we are co-authors, this won’t just be the standard interview format, how do you think we should do it? And what should we ask each other?

“Context is that which is scarce”

A number of you have been asking me about this maxim, so here is some background on what it means:

1. Ever try to persuade another person? Let’s say it is even of an uncontested idea such as supply and demand. You might “final exam them into admitting that the demand curve slopes downward.” But still, if they do not understand enough of the uses of supply and demand thinking, they will find it hard to think in terms of supply and demand themselves. They will not have the background context to understand the import of the idea.

2. Why did economists for so long stick with cost of production theories of value, rather than adopting the marginal revolution? They didn’t see or understand all the possibilities that would open up from bringing the marginal calculus to microeconomics, and then later to empirical work. Given the context they had, which was for performing simple comparative statics experiments on developing economies, the cost of production theory seemed good enough.

3. One correspondent from a successful company wrote me:

“- I’ve been onboarding ~5 people every two weeks for my team.

– The number of them that actually learn all the important stuff in under a month is zero. The number of them that have a self-guided strategy to learn what is relevant is almost zero.

– Remember these are people with fancy college degrees, that passed a hard interview, and are getting paid $X00k!

– I’m now spending entire days writing / maintaining an FAQ, producing diagrams, and having meetings with them to answer their questions.”

4. Ever wonder about the vast universe of critically acclaimed aesthetic masterworks, most of which you do not really fathom? If you dismiss them, and mistrust the critics, odds are that you are wrong and they are right. You do not have the context to appreciate those works. That is fine, but no reason to dismiss that which you do not understand. The better you understand context, the more likely you will see how easily you can be missing out on it.

5. I use “modern art” or “contemporary art” (both bad terms, by the way) as good benchmarks for whether a person understands “context is that which is scarce.” “Contemporary classical music” too (another bad terms, but you know what I mean). If a person is convinced that those are absurd enterprises, that is a good litmus test for that person not understanding the import of context. You may not prefer things to be this way, but in many cultural areas appreciation of the outputs demands more and more context (Adam Smith called this division of labor, by the way).

6. If you think a great deal of things are “downstream from culture and ideas,” as I do, you also have to think they are downstream of context.

7. Many attributions of bad motives to people, or attributions of conspiracy, spring from a lack of understanding of context. It is easy enough for someone to seem like he or she is “operating in bad faith.” But usually a deeper and better understanding is available.

8. Lack of context is often a serious problem on Twitter and other forms of social media, as they may deliberately truncate context. In some parts of our culture, context is growing more scarce. “When I’m Sixty-Four” makes much more sense on Sgt. Pepper than it does on Spotify.

9. So much of education is teaching people context. That is why it is hard, and also why it often does not seem like real learning.

10. When judging people for leadership positions, or for jobs that require strongly synthetic abilities, you should consider how well they are capable of generating an understanding of context across a broad range of domains, including ex nihilo, so to speak. How to test for understanding of context is itself a topic we could consider in more depth.

Addendum: MR, by the way, or at least my contributions to it, is deliberately written to give you less than full context. It is assumed that you are up to speed on the relevant discourse, and are hungering for the latest tidbit on top of where you are currently standing. Conversations with Tyler also are conducted on a “I’m just going to assume you have the relevant context and jump right in” — that is not ideal for many people, or they may like the performance art of it without it furthering their understanding optimally. But it keeps me motivated because for me the process is rarely boring. I figure that is more important than keeping you all happy. It also attracts smarter and better informed readers and listeners, which in turn helps me keep smart and alert. I view my context decisions, in particular the choice to go “minimal upfront context” in so many settings, as essential to my ongoing program of self-education.

How to start art collecting

The answer here depends so much on how much money and how much time and how much interest you have that I can’t give you a simple formula. Nonetheless here are a few basic observations that might prove useful at varying levels of interest:

1. At some you should just start buying some stuff. You’re going to make some mistakes at first, treat that as part of your learning curve and as part of the price of the broader endeavor.

2. Don’t ever think you can make money buying and selling art. The bid-ask spread is a bitch, and finding the right buyers is a complex and time-consuming matching problem.

3. Art is strongly tiered in a hierarchical fashion. That means most fields are incredible bargains, at least relative to the trendy fields. A lot of HNW buyers are looking for large, striking contemporary works they can hang over their sofas in their second homes in Miami Beach or Los Angeles or Aspen. Good for them, as many of those works are splendid. Nonetheless that opens up opportunities for you. I find the price/beauty gradient ratio can be especially favorable for textiles, ethnographic works, Old Master drawings (and sometimes paintings), paintings from smaller or obscure countries, various collectibles, and many other areas.

4. As for the price/beauty gradient, prints, lithographs, and watercolors usually are much cheaper than original paintings. And they are not necessarily of lower quality. Figure out early on which are the artists whose prints can be as good or better than many of their original works (Lozowick, Picasso, and Johns would be a few nominees) and learn lots about those areas. A Goncharova painting can costs hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars, but one of her Ballet Russe designs — an original done by the same hand — can go for thousands.

4b. The “mainstream art market” still discriminates in favor of “original” works, but it already has started laying this convention aside for photographs, and I wonder if further erosion along these lines is not on the way. The “internet generation” is getting wealthier all the time, and do they all hate reproducibility so much?

5. Pick a small number of areas and specialize in them. Learn everything you can about them. Everything. Follow auction results. Read about their history. Read biographies of their creators. Go visit exhibitions. And so on. It is also a great way to learn about the world more generally.

6. If you are an outsider, you can’t just walk up to a gallery and buy the best stuff at a market clearing price. You have to invest in your relationships there. Or consider buying at auction. Whatever your choice, be aware of the logic and why things work that way. Selling practices are also an exercise in reputation management of the artist and of the gallery, and maybe they think you are not up to snuff as a buyer!

7. Visit other people’s art collections as much as you can. You will learn a great deal this way, and learn to spot new forms of foolishness that you had never before imagined.

8. Don’t treat art collecting as like shopping, or as motivated by the same impulses. If you do, you will accumulate a lot of junk very quickly. Thinking of it more as building out a long term narrative of what an artistic field, and a culture, is all about. Fine if you don’t want to do that! It is a demanding exercise, and if you wish to escalate your collecting to higher levels, you need to ask yourself if you are really up for that. Does it sound like something you would be good at?

9. Fakes are rampant in so many parts of the art world, but they are especially likely if the artist is “popular” (e.g., Chagall, Dali) or if the style is easily copied ex post (Malevich). In contrast, if you buy a piece of complex stained glass, it is probably the real thing. The major auction houses are usually reasonably good at rooting out fakes, but there is no institution you can trust 100 percent. And sometimes, as with the recently auction Botticelli and da Vinci paintings, no one really knows for sure (Botticelli pro and con; in any case I don’t like the work, certainly not for $45 million).

10. Don’t buy art on the basis of the artist’s name. This is a good way to end up with a lot of crap and, for that matter, fakes. Just about every famous artist has a fair number of mediocre works, overpriced at that. (That said, if you really just want to “collect names,” you will find it is remarkable on a limited income just how many top names you can wrack up.)

11. Few of the important art collections were built by just throwing tons of money at the task. That is a recipe for being ripped off, and it attracts poor quality sellers to your orbit. You have to understand something more deeply than other people do. Obviously money helps, but you can’t rely on outbidding others as your most important ally.

12. Maybe sometime I’ll tell you the story of how I obtained an especially fine, rare work by throwing a stone at a wild dog in rural Mexico. Or how I tracked another painter down at the mental hospital.

13. Get a mentor!

There is much more I could say of relevance (e.g., how to present yourself to dealers? how to avoid winner’s curse?), but I’ll stop there for now.

Ayn Rand’s Frank Lloyd Wright Cottage

Ayn Rand commissioned a house from Frank Lloyd Wright. Beautiful. Alas it was never built.

A simple theory of culture

The transistor radio/car radio was the internet of its time. Content was free, and there were multiple radio stations, though not nearly as many as we have internet sites.

People tuned into the radio, in part, for ideas, not just tunes. But the ideas that spread best were attached to songs. Drug use spread, in part, because famous musicians sang about using drugs. Anti-Vietnam War themes spread through songs, as did many other social movements. Overall, ideas that could be bundled with songs had a big advantage. And since new songs were largely the province of young people, this in turn favored ideas for young people.

Popular music was highly emotionally charged because so much of it was connected to ideas you really cared about.

Of course, by attaching an idea to a song you often ensured the idea wasn’t going to be really subtle, at least not along the standard intellectual dimensions. But it might be correct nonetheless.

Today you can debate ideas directly on social media, without the intermediation of music. Ideas become less simple and more baroque, while music loses its cultural centrality and becomes more boring.

We also don’t need to tie novels so much to ideas, although in countries such as Spain idea-carrying novels remain a pretty common practice (NYT). A lot of painting and sculpture also seem increasingly disconnected from significant social ideas.

In this new world, celebrities decline in relative influence, because they too are no longer carriers of ideas in the way they used to be. Think “John Wayne!” Arguably “celebrity culture” peaked in the 1980s with Madonna and the like.

When I hear various complaints about the contemporary scene, sometimes I ask myself: “Is this really a complaint about the disintermediation of ideas”?

In this view, the overall modern “portfolio” may be better, but the best individual art works, and in turn the greatest artists, will come from the earlier era.

What should I ask Lydia Davis?

I will be doing a Conversation with her, and here is part of her Wikipedia page:

Lydia Davis (born July 15, 1947) is an American short story writer, novelist, essayist, and translator from French and other languages, who often writes extremely brief short stories. Davis has produced several new translations of French literary classics, including Swann’s Way by Marcel Proust and Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert.

So what should I ask her?

What to Watch

Some things I have watched, some good, some not so good.

Cobra Kai on Netflix: A reliable, feel good show, well plotted. It plays like they mapped each season in advance covering all permutations and combinations of friends turning into enemies and enemies turning into friends. Do I really need five seasons of the same thing? No. But I still watch. Popcorn material.

Maid on Netflix: I appreciated the peek into the difficulties of managing the welfare system and pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps when your family is pulling you down. Margaret Qualley (Andie MacDowell’s daughter who plays her mother on the show) has an odd charisma. It’s been noted that she is an impossibly perfect mother. Less noted is that she is a terrible wife, a poor daughter to her father and a bad girlfriend. Everyone deserves a break is the message we get from this show, except men. Still, it was well done.

The Last Duel is one of Ridley’s best. Superb, subtle acting from Jodie Comer–deserving of Oscar. Slightly too long but there are natural breaking points for at home watching. N.B. given the times it can’t be interpreted ala Rashômon as many people suggest but rather the last word is final which reduces long term interest but I still liked it.

Alex Rider on Amazon: It’s in essence a James Bond origin story. If that sounds like something you would enjoy, you will. I am told the books are also good for YA.

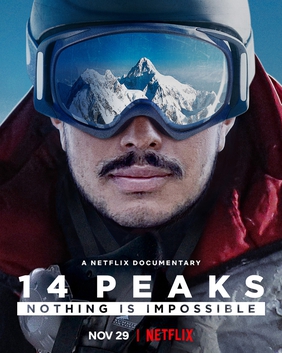

14 Peaks: Nothing is Impossible: A mountain documentary following Nimsdai Purja as he and his team attempt to summit all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks in seven months. In many ways, the backstory–Purja is a Gurka and British special forces solider–is even more interesting. It does say something that most people don’t know his name.

14 Peaks: Nothing is Impossible: A mountain documentary following Nimsdai Purja as he and his team attempt to summit all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks in seven months. In many ways, the backstory–Purja is a Gurka and British special forces solider–is even more interesting. It does say something that most people don’t know his name.

The Eternals on Disney: Terrible. Didn’t finish it. A diverse cast with no actual diversity. Kumail Nanjiani, Dinesh from Silicon Valley, plays his super hero like Dinesh from Silicon Valley. Karun, the Indian sidekick, is the most authentic person in the whole ensemble. Aside from being boring it’s also dark, not emotionally but visually. It doesn’t matter the scene, battle scenes, outdoor scenes, kitchen table scenes–all so dark they are literally hard to see.

Wheel of Time: It’s hard to believe they spent a reported $10 million per episode on this clunker. The special effects were weak, the editing was bad, the mood-setting and world building were poor. The actors have no chemistry. Why would anyone be interested in Egwene who shows no spunk, intelligence or charisma? For better in this genre is The Witcher on Netflix.

The French Dispatch (theatres and Amazon): I loved it. Maybe the most Wes Anderson of Wes Anderson movies, so be prepared. Every scene has something interesting going on and there’s a new scene every few minutes. A send-up and a love story to the New Yorker. Lea Seydoux is indeed, shall we say, inspiring.

Samsung markets in everything

What would Marshall McLuhan say?:

Staring at your non-fungible tokens on a smartphone or laptop screen is fine and all, but why not remind everyone who visits your home of the money you spent on digital art NFTs by showcasing them on your TV screen? Somehow we’re in a world where that’s about to become reality: Samsung says it’s planning extensive support for NFTs beginning with its 2022 TV lineup.

Here is the full story, via the excellent Samir Varma.

Dan Wang’s 2021 letter

Here it is, one of the better written pieces of this (or last) year. It is mostly about China, manufacturing, and economic policy, but here is the part I will quote:

But Hong Kong was also the most bureaucratic city I’ve ever lived in. Its business landscape has remained static for decades: the preserve of property developers that has created no noteworthy companies in the last three decades. That is a heritage of British colonial rule, in which administrators controlled economic elites by allocating land—the city’s most scarce resource—to the more docile. Hong Kong bureaucrats enforce the pettiest rules, I felt, out of a sense of pride. On the mainland, enforcers deal often enough with senseless rules that they are sometimes able to look the other way. Thus a stagnant spirit hangs over the city. I’ve written before that Philip K. Dick is useful not for thinking about Hong Kong’s skyline, but its tycoon-dominated polity: “governed by a competent but fundamentally pessimistic elite, which administers a population bent on consumption. Instead of being hooked on drugs and television like in PKD’s novels, people in Hong Kong are addicted to the extraordinary flow of liquidity from the mainland, which raises their asset values and dulls their senses.”

And then on Mozart:

Among these three works, Figaro is the most perfect and Don Giovanni the greatest. But I believe that Cosi is the best. Cosi is Mozart’s most strange and subtle opera, as well as his most dreamlike. If the Magic Flute might be considered a loose adaptation of Shakespeare’s Tempest—given their themes of darkness, enchantment, and salvation—then Cosi ought to be Mozart’s take on A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Donald Tovey called Cosi “a miracle of irresponsible beauty.” It needs to be qualified with “irresponsible” because its plot is, by consensus, idiotic. The premise is that two men try—on a dare—to seduce the other’s lover. A few fake poisonings and Albanian disguises later, each succeeds, to mutual distress. Every critic that professes to love the music of Cosi also discusses the story in anguished terms. Bernard Williams, for example, noted how puzzling it has been that Mozart chose to vest such great emotional power with his music into such a weak narrative structure. Joseph Kerman is more scathing, calling it “outrageous, immoral, and unworthy of Mozart.”

I readily concede that the music of Cosi so far exceeds its dramatic register.

Recommended! There is much more at the link, substantive throughout. Though I should note I am less bullish on both manufacturing and China than Dan is. I fully agree about Bleak House, however, and at times I think it is the greatest novel written…

What has Jasper Johns done for us lately?

What has Johns done for us lately? Pretty much what he did for us in the first place: he continually disrupts the mental shorthand that converts complex visual experience into simpler mental categories, with all their buttressing opinions, received wisdom, and personal preferences. In a world (including the art world) where “visuals” are used to simplify arguments and kindle beliefs, Johns reminds us that doubling, bifurcation, and uncertainty are the terms of vision itself.

That is from Susan Tallman in the New York Review of Books. Happy New Year everybody!

The Jeff Holmes Conversation with Tyler Cowen

Jeff is the CWT producer, and it has become our custom to do a year-end round-up and summary. Here is the transcript and audio and video. Here is one excerpt:

HOLMES: …Okay, let’s go through your 2011 list really quickly.

COWEN: Sure.

HOLMES: All right, number one — in no particular order, I think — but number one was Incendies. Do you remember what that’s about?

COWEN: That is by the same director of Dune.

HOLMES: Oh, is that Denis Villeneuve?

COWEN: Yes, that’s his breakthrough movie. It’s incredible.

HOLMES: I didn’t know that. I’d never heard of it. French Canadian movie, mostly set in Lebanon.

COWEN: Highly recommended, whether or not you like Dune. That was a good pick. It’s held up very well. The director has proven his merits repeatedly, and the market agrees.

HOLMES: I’m a fan of Denis Villeneuve. Obviously, Arrival was great. I can’t think of the Mexican drug movie off the top of my head.

COWEN: Is it Sicario?

HOLMES: Sicario — awesome.

COWEN: It was interesting, yes.

HOLMES: He is one of the only directors today where, when he now makes something, I know I will go and see it.

COWEN: Well, you must see Incendies. So far, I’m on a roll. What’s next?

HOLMES: All right, number two: Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives.

COWEN: Possibly the best movie of the last 20 years. I’m impressed by myself. It’s a Thai movie. It’s very hard to explain. I’ve seen it three times since. A lot of other people have it as either their favorite movie ever or in a top-10 status, but a large screen is a benefit. If you’re seeing the movie, pay very close attention to its sounds and to the sonic world it creates, not just the images.

There are numerous interesting observations in the dialogue, including about some of the guests and episodes.

Self-recommended!

Merry Christmas!

My Conversation with the excellent Ruth Scurr

A fine discourse all around, here is the transcript and audio. Here is part of the CWT summary:

Ruth joined Tyler to discuss why she considers Danton the hero of the French Revolution, why the Jacobins were so male-obsessed, the wit behind Condorcet’s idea of a mechanical king, the influence of Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments during and after the Reign of Terror, why 18th-century French thinkers were obsessed with finding forms of government that would fit with emerging market forces, whether Hayek’s critique of French Enlightenment theorists is correct, the relationship between the French Revolution and today’s woke culture, the truth about Napoleon’s diplomatic skills, the poor prospects for pitching biographies to publishers, why Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws would be her desert island read, why Cambridge is a better city than Oxford, why the Times Literary Supplement remains important today, what she loves about Elena Ferrante’s writing, how she stays open as a biographer, and more.

And an excerpt:

COWEN: Is there a counterfactual path where the French Revolution simply works out well as a liberal revolution? If so, what would have needed to have been different?

SCURR: In terms of counterfactuals, the one I thought most about was, What would have happened if Robespierre hadn’t fallen at Thermidor and the relationship between him and [Louis Antoine Léon de] Saint-Just had continued? But that’s not the triumph of the liberal revolution. That would have merely been a continuation of the point they had gotten to. For a triumph of the liberal revolution, that would have needed to be much, much earlier.

I think that it was almost impossible for them to get a liberal constitution in place in time to make that a possibility. What you have is 1789, the liberal aspirations, the hopes, the Declaration of Rights; and then there is almost a hiatus period in which they are struggling to design the institutions. And that is the period which, if it could have been compressed, if there could have been more quickly a stability introduced . . .

Some of the people I’m most interested in in that period were very interested in what has to be true about the society in order for it to have a stable constitution. Obviously when you’re in the middle of a revolution and you’re struggling to come up with those solutions, then there is the opening to chaos.

Definitely recommended. And I am again happy to recommend Ruth’s new book Napoleon: A Life Told in Gardens and Shadows.

My Conversation with David Rubinstein

Here is the audio, video, and transcript — David has a studio in his home! Here is part of the CWT summary:

He joined Tyler to discuss what makes someone good at private equity, why 20 percent performance fees have withstood the test of time, why he passed on a young Mark Zuckerberg, why SPACs probably won’t transform the IPO process, gambling on cryptocurrency, whether the Brooklyn Nets are overrated, what Wall Street and Washington get wrong about each other, why he wasn’t a good lawyer, why the rise of China is the greatest threat to American prosperity, how he would invest in Baltimore, his advice to aging philanthropists, the four standards he uses to evaluate requests for money, why we still need art museums, the unusual habit he and Tyler share, why even now he wants more money, why he’s not worried about an imbalance of ideologies on college campuses, how he prepares to interview someone, what appealed to him about owning the Magna Carta, the change he’d make to the US Constitution, why you shouldn’t obsess about finding a mentor, and more.

Here is an excerpt from the dialogue:

COWEN: Why do so many wealthy people have legal backgrounds, but the very wealthiest people typically do not?

RUBENSTEIN: Lawyers tend to be very process-oriented and very systematic, and as a result, they tend not to take big leaps of faith because you’re taught in law school to worry about precedent. Precedent is not what makes entrepreneurs successful. You have to ignore precedent, and you’ll break through walls and say you can’t be worried about what the precedent was.

If you’re worried about precedent, you’ll never make a leap of faith to create a company like Apple or a company like Amazon. Lawyers tend to be more, I would say, tradition-oriented, more process-oriented, and more precedent-oriented than great entrepreneurs are.

And:

COWEN: You seem to be in good health. What if someone makes the argument to you, “You would do the world more good by not giving away money now, but investing it through private equity, earning whatever percent you could earn, and when you’re a bit older, give much more away. You can always give more to philanthropy five years down the road.”

RUBENSTEIN: Of course, you never know when you’re going to die, and COVID — we lost 700,000 Americans in COVID. I could have been one of them. I’m 72 years old. If you wait too long to give away your money, you might find your executor giving it away. Secondly —

COWEN: But you could even write that into your will if you wanted. You’d have more to give away, maybe 15 percent a year.

RUBENSTEIN: Yes, but if you take the view that happy people live longer, and if giving away money while you’re alive and you’re seeing it being given away makes you happier, you might live longer. Grumpy people, my theory is, don’t live as long. Happy people live longer.

If giving away money and having people say to me, “You’re doing something good for the country,” makes me feel good, it might make me live longer. If I waited till the last moment to give away the money, it might be too late to have that feel-good experience.

And please note that David has a new book out, The American Experiment: Dialogues on a Dream.

My Conversation with David Salle

I was honored to visit his home and painting studio, here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the CWT summary:

David joined Tyler to discuss the fifteen (or so) functions of good art, why it’s easier to write about money than art, what’s gone wrong with art criticism today, how to cultivate good taste, the reasons museum curators tend to be risk-averse, the effect of modern artistic training on contemporary art, the evolution of Cézanne, how the centrality of photography is changing fine art, what makes some artists’ retrospectives more compelling than others, the physical challenges of painting on a large scale, how artists view museums differently, how a painting goes wrong, where his paintings end up, what great collectors have in common, how artists collect art differently, why Frank O’Hara was so important to Alex Katz and himself, what he loves about the films of Preston Sturges, why The Sopranos is a model of artistic expression, how we should change intellectual property law for artists, the disappointing puritanism of the avant-garde, and more.

And excerpt:

COWEN: Yes, but just to be very concrete, let’s say someone asks you, “I want to take one actionable step tomorrow to learn more about art.” And they are a smart, highly educated person, but have not spent much time in the art world. What should they actually do other than look at art, on the reading level?

SALLE: On the reading level? Oh God, Tyler, that’s hard. I’ll have to think about it. I’ll have to come back with an answer in a few minutes. I’m not sure there’s anything concretely to do on the reading level. There probably is — just not coming to mind.

There’s Henry Geldzahler, who wrote a book very late in his life, at the end of his life. I can’t remember the title, but he addresses the problem of something which is almost a taboo — how do you acquire taste? — which is, in a sense, what we’re talking about. It’s something one can’t even speak about in polite society among art historians or art critics.

Taste is considered to be something not worth discussing. It’s simply, we’re all above that. Taste is, in a sense, something that has to do with Hallmark greeting cards — but it’s not true. Taste is what we have to work with. It’s a way of describing human experience.

Henry, who was the first curator of modern and contemporary art at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, was a wonderful guy and a wonderful raconteur. Henry basically answers your question: find ways, start collecting. “Okay, but I don’t have any money. How can I collect art?” You don’t have to collect great paintings. Just go to the flea market and buy a vase for 5 bucks. Bring it back to your room, live with it, and look at it.

Pretty soon, you’ll start to make distinctions about it. Eventually, if you’re really paying attention to your own reactions, you’ll use it up. You’ll give that to somebody else, and you’ll go back to the flea market, and you buy another, slightly better vase, and you bring that home and live with that. And so the process goes. That’s very real. It’s very concrete.

And:

COWEN: As you know, the 17th century in European painting is a quite special time. You have Velásquez, you have Rubens, you have Bruegel, much, much more. And there are so many talented painters today. Why can they not paint in that style anymore? Or can they? What stops them?

SALLE: Artists are trained in such a vastly different way than in the 17th, 18th, or even the 19th century. We didn’t have the training. We’re not trained in an apprentice guild situation where the apprenticeship starts very early in life, and people who exhibit talent in drawing or painting are moved on to the next level.

Today painters are trained in professional art schools. People reach school at the normal age — 18, 20, 22, something in grad school, and then they’re in a big hurry. If it’s something you can’t master or show proficiency in quickly, let’s just drop it and move on.

There are other reasons as well, cultural reasons. For many years or decades, painting in, let’s say, the style of Velásquez or even the style of Manet — what would have been the reason for it? What would have been the motivation for it, even assuming that one could do it? Modernism, from whenever we date it, from 1900 to 1990, was such a persuasive argument. It was such an inclusive and exciting and dynamic argument that what possibly could have been the reason to want to take a step back 200 years in history and paint like an earlier painter?

It is a bit slow at the very beginning, otherwise excellent throughout.