Category: Travel

My Conversation with the excellent Jonny Steinberg

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

Tyler considers Winnie and Nelson: Portrait of a Marriage one of the best books of the last decade, and its author Jonny Steinberg one of the most underrated writers and thinkers—in North America, at least. Steinberg’s particular genius lies in getting uncomfortably close to difficult truths through immersive research—spending 350 hours in police ride-alongs, years studying prison gangs and their century-old oral histories, following a Somali refugee’s journey across East Africa—and then rendering what he finds with a novelist’s emotional insight.

Tyler and Jonny discuss why South African police only feel comfortable responding to domestic violence calls, how to fix policing, the ghettoization of crime, how prison gangs regulate behavior through century-old rituals, how apartheid led to mass incarceration and how it manifested in prisons, why Nelson Mandela never really knew his wife Winnie and the many masks they each wore, what went wrong with the ANC, why the judiciary maintained its independence but not its quality, whether Tyler should buy land in Durban, the art scene in Johannesburg, how COVID gave statism a new lease on life, why the best South African novels may still be ahead, his forthcoming biography of Cecil Rhodes, why English families weren’t foolish to move to Rhodesia in the 1920s, where to take an ideal two-week trip around South Africa, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: My favorite book of yours again is Winnie and Nelson, which has won a number of awards. A few questions about that. So, they’re this very charismatic couple. Obviously, they become world-historical famous. For how long were they even together as a pair?

STEINBERG: Very, very briefly. They met in early 1957. They married in ’58. By 1960, Mandela was no longer living at home. He was underground. He was on the run. By 1962, he was in prison. So, they were really only living together under the same roof for two years.

COWEN: And how well do you feel they knew each other?

STEINBERG: Well, that’s an interesting question because Nelson Mandela was very, very in love with his wife, very besotted with his wife. He was 38, she was 20 when they met. She was beautiful. He was a notorious philanderer. He was married with three children when they met. He really was besotted with her. I don’t think that he ever truly came to know her. And when he was in prison, you can see it in his letters. It’s quite remarkable to watch. She more and more becomes the center of meaning in his life, his sense of foundation, his sense of self as everything else is falling away.

And he begins to love her more and more, and even to coronate her more and more so that she doesn’t forget him. His letters grow more romantic, more intense, more emotional. But the person he’s so deeply in love with is really a fiction. She’s living a life on the outside. And you see this very troubling line between fantasy and reality. A man becoming deeply, deeply involved with a woman who is more and more a figment of his imagination.

COWEN: Do you think you learned anything about marriage more generally from writing this book?

STEINBERG: [laughs] One of the sets of documents that I came across in writing the book were the transcripts of their meetings in the last 10 years of his imprisonment. The authorities bugged all of his meetings. They knew they were being bugged, but nonetheless, they were very, very candid with each other. And you very unusually see a marriage in real time and what people are saying to each other. And when I read those lines, 10 different marriages that I know passed through my head: the bickering, the lying, the nasty things that people do to one another, the cruelties. It all seemed very familiar.

COWEN: How is it you think she managed his career from a distance, so to speak?

STEINBERG: Well, she was a really interesting woman. She arrived in Johannesburg, 20 years old in the 1950s, where there was no reason to expect a woman to want a place in public life, particularly not in the prime of public life. And she was absolutely convinced that there was no position she should not occupy because she was a woman. She wanted a place in politics; she wanted to exercise power. But she understood intuitively that in that time and place, the way to do that was through a man. And she went after the most powerful rising political activists available.

I don’t think it was quite as cynical as that. She loved him, but she absolutely wanted to exercise power, and that was a way to do it. Once she became Mrs. Mandela, I think she had an enormously aristocratic sense of politics and of entitlement and legitimacy. She understood herself to be South Africa’s leader by virtue of being married to him, and understood his and her reputations as her projects to endeavor to keep going. And she did so brilliantly. She was unbelievably savvy. She understood the power of image like nobody else did, and at times saved them both from oblivion.

COWEN: This is maybe a delicate question, but from a number of things I read, including your book, I get the impression that Winnie’s just flat out a bad person…

Interesting throughout, this is one of my favorite CWT episodes, noting it does have a South Africa focus.

What should I ask Dan Wang?

Yes, I will be doing a podcast with him. Dan first became famous on the internet with his excellent Christmas letters. More recently, Dan is the author of the NYT bestselling book Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future.

Here is Dan Wang on Wikipedia, here is Dan on Twitter. I have known him for some while. So what should I ask him?

What should I ask Blake Scholl?

The Boom guy doing supersonic flight! I will be doing a podcast with him at the forthcoming Roots of Progress Institute event. He already has told “his story” on the supersonic side a number of times, so what else of interest should we cover? For background, here is Blake on Wikipedia.

What to read for travel

When you land in a new destination, what should you read? It’s hard to find good material with search engines because the space is SEO’d so aggressively. A Wikipedia article is fine insofar as it goes, but inevitably misses much of the texture of a place. I think it’d be neat if there was some kind of service that collated great travel writing — especially pieces that capture something of the context of a place. (See the Davies post below.) To this end, I made guide.world.

From Patrick Collison, recommended, lots of great reading (and travel) there.

My excellent Conversation with David Commins

Saudi Arabia and the Gulf are the topics, here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

David Commins, author of the new book Saudi Arabia: A Modern History, brings decades of scholarship and firsthand experience to explain the kingdom’s unlikely rise. Tyler and David discuss why Wahhabism was essential for Saudi state-building, the treatment of Shiites in the Eastern Province and whether discrimination has truly ended, why the Saudi state emerged from its poorer and least cosmopolitan regions, the lasting significance of the 1979 Grand Mosque seizure by millenarian extremists, what’s kept Gulf states stable, the differing motivations behind Saudi sports investments, the disappointing performance of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology despite its $10 billion endowment, the main barrier to improving its k-12 education, how Yemen became the region’s outlier of instability and whether Saudi Arabia learned from its mistakes there, the Houthis’ unclear strategic goals, the prospects for the kingdom’s post-oil future, the topic of David’s next book, and more.

And an excerpt:

COWEN: Now, as you know, the senior religious establishment is largely Nejd, right? Why does that matter? What’s the historical significance of that?

COMMINS: Right. Nejd is the region of central Arabia. Riyadh is currently the capital. The first Saudi empire had a capital nearby, called Diriyah. Nejd is really the territory that gave birth to the Wahhabi movement, it’s the homeland of the Saud dynasty, and it is the region of Arabia that was most thoroughly purged of the older Sunni tradition that had persisted in Nejd for centuries.

Consequently, by the time that the Saudi government developed bureaucratic agencies in the 1950s and ’60s, the religious institution was going to recruit from that region of Arabia primarily. Now, it certainly attracted loyalists from other parts of Arabia, but the Wahhabi mission, as I call it — their calling to what they considered true belief — began in Nejd and was very strongly identified with the towns of Nejd ever since the late 1700s.

COWEN: Would I be correct in inferring that some of the least cosmopolitan parts of Saudi Arabia built the Saudi state?

COMMINS: Yes, that is correct. That is correct. If you think of the 1700s and 1800s, the Red Sea and Persian Gulf coast of Arabia were the most cosmopolitan parts of Arabia.

COWEN: They’re richer, too, right? Jeddah is a much more advanced city than Riyadh at the time.

COMMINS: Somewhat more advanced. Yes, it is more advanced, it is more cosmopolitan than Nejd. There is the regional identity in Hejaz, that is the Red Sea coast where the holy cities and Jeddah are located. The townspeople there tended to look upon Nejd as a less advanced part of Arabia. But again, that’s a very recent historical development.

COWEN: How is it that the coastal regions just dropped the ball? You could imagine some alternate history where they become the center of Saudi power and religious thought, but they’re not.

COMMINS: Right. If you take Jeddah, Mecca, and Medina — that region of Arabia, known as Hejaz, had always been under the rule of other Muslim empires. They were under the rule of other Muslim powers because of the religious value of possessing, if you will, the holy cities, Mecca and Medina. From the time of the first Muslim dynasty that was based in Damascus in the seventh and early eighth centuries, all the way until the Ottoman Empire, Muslim dynasties outside Arabia coveted control of that region. They were just more powerful than local resources could generate.

Hejaz was always, if you were, to dependency on outside Muslim powers. If you look at the east coast of Arabia — what’s now the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf — it was richer than central Arabia. It’s the largest oasis in Arabia. It is in proximity to pearling banks, which were an important source for income for residents there. It was part of the Indian Ocean trade between Iraq and India. The population there was always — well, always — for the last thousand years has been dominated by Bedouin tribesmen.

There was a brief Ismaili Shia republic, you might say, in that part of Arabia in medieval times. It just didn’t have, it seems, the cohesion to conquer other parts of Arabia. That’s what makes the Saudi story really remarkable, is that they were able to muster and sustain the cohesion to carry out a conquest like that over the course of 50 years.

COWEN: Physically, how did they manage that? Water is a problem, a lot of transport is by camel, there’s no real rail system, right?

Recommended, full of historical information about a generally neglected region, neglected from the point of view of history at least rather than current affairs.

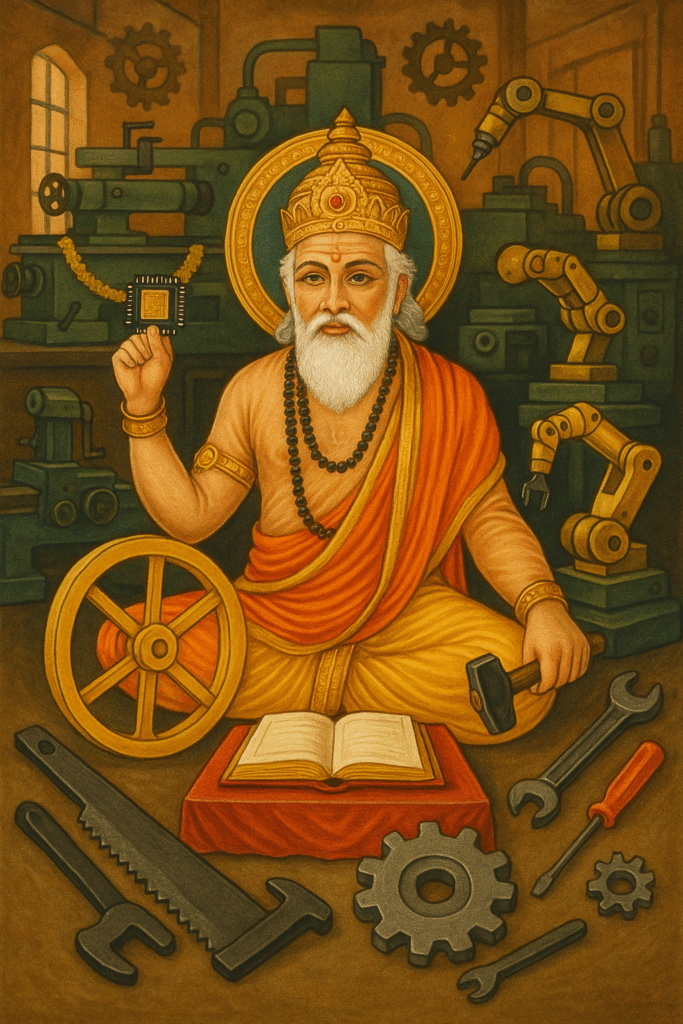

Celebrate Vishvakarma: A Holiday for Machines, Robots, and AI

Most holidays celebrate people, gods or military victories. Today is India’s Vishvakarma Puja, a celebration of machines. In India on this day, workers clean and honor their equipment and engineers pay tribute to Vishvakarma, the god of architecture, engineering and manufacturing.

Most holidays celebrate people, gods or military victories. Today is India’s Vishvakarma Puja, a celebration of machines. In India on this day, workers clean and honor their equipment and engineers pay tribute to Vishvakarma, the god of architecture, engineering and manufacturing.

Call it a celebration of Solow and a reminder that capital, not just labor, drives growth.

Capital today isn’t just looms and tractors—it’s robots, software, and AI. These are the new force multipliers, the machines that extend not only our muscles but our minds. To celebrate Vishvakarma is to celebrate tools, tool makers and the capital that makes us productive.

We have Labor Day for workers and Earth Day for nature. Viskvakarma Day is for the machines. So today don’t thank Mother Earth, thank the machines, reflect on their power and productivity and be grateful for all that they make possible. Capital is the true source of abundance.

Vishvakarma Day should be our national holiday for abundance and progress.

Hat tip: Nimai Mehta.

UAP okie-dokie

The real action starts at 0:54:

Here is the same video with under oath reactions from witness experts. Here are remarks from Dylan Borland.

Housing 101

John Arnold points us to this table on new apartments and pointedly notes that the population of LA (18.5 m) is more than 7 times that of Austin (2.5m).

MR readers will not be surprised to learn that apartment prices are falling in Austin.

Meanwhile the WSJ reports another shocker, New York’s Airbnb Crackdown, in Force for Two Years, Hasn’t Improved Housing Supply. But guess what has happened? Ok, you don’t have to guess. Hotel prices have increased:

Hotels tend to benefit from tighter Airbnb restrictions, especially in New York City. Significantly reducing the number of apartments that can be rented for less than 30 days undeniably boosts demand for hotel rooms in a city visited by tens of millions of tourists a year.

Without the law, “we would be in a catastrophic situation,” said hotelier Richard Born, who owns 24 hotels across the city.

Eli Dourado on trains and abundance

One thing I got a bit of crap for in the hallways of the Abundance conference is my not infrequent mockery of trains on Twitter. I’m sorry, trains are not an abundance technology. I think many people in the abundance scene like trains because:

1. America’s inability to build HSR is the leading example of low state capacity, and we all more or less agree that state capacity is a tenet of the abundance agenda.

2. Trains have high transport efficiency, and people coming to abundance out of the climate movement can’t shake their old habits of caring about energy efficiency ahead of other considerations.

Obviously if we spend billions of dollars on high-speed rail, there should at least be some high-speed rail service. But a deeper element of state capacity is not picking dumb things for the state to build in the first place. And trains are a dumb thing to build in the 21st century.

A true transportation abundance agenda has to revolve around airplanes and autonomous vehicles. The goal should be able to go from any point in the country to any other point in the country in, like, two hours, door to door.

We should have supersonic airplanes made out of cheap titanium and powered by electro-LCH4. An autonomous vehicle should be available to pick you up within 30 seconds and whisk you to a nearby airfield. Security should be painless and instant (another state capacity task). If your trip doesn’t require an airplane, the autonomous vehicle should get you straight there at 100+ mph since it’s good at avoiding accidents. In cities, autonomous buses with dynamic route planning based on riders’ actual needs beat subways’ 1-dimensional tracks.

We should not be trying to build marginally better versions of 20th century (or 19th century!) technology. We should be more ambitious than that. Trains are unbefitting of a country as wealthy as I aspire for us to be.

Please join the anti-train faction of the abundance movement.

Here is the link to the tweet.

My very interesting Conversation with Seamus Murphy

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

Seamus Murphy is an Irish photographer and filmmaker who has spent decades documenting life in some of the world’s most challenging places—from Taliban-controlled Afghanistan to Nigeria’s Boko Haram territories. Having left recession-era Ireland in the 1980s to teach himself photography in American darkrooms, Murphy has become that rare artist who moves seamlessly between conflict zones and recording studios, creating books of Afghan women’s poetry while directing music videos that anticipated Brexit.

Tyler and Seamus discuss the optimistic case for Afghanistan, his biggest fear when visiting any conflict zone, how photography has shaped perceptions of Afghanistan, why Russia reminded him of pre-Celtic Tiger Ireland, how the Catholic Church’s influence collapsed so suddenly in Ireland, why he left Ireland in the 1980s, what shapes Americans impression of Ireland, living part-time in Kolkata and what the future holds for that “slightly dying” but culturally vibrant city, his near-death encounters with Boko Haram in Nigeria, the visual similarities between Michigan and Russia, working with PJ Harvey on Let England Shake and their travels to Kosovo and Afghanistan together, his upcoming film about an Afghan family he’s documented for thirty years, and more.

And an excerpt:

COWEN: Now you’re living in Kolkata mainly?

MURPHY: No. I’m living in London, some of the year in Kolkata.

COWEN: Why Kolkata?

MURPHY: My wife is Indian. She grew up in Delhi, Bombay, and Kolkata, but Kolkata was her favorite. They were the years that were her most fond of years. She’s got lots of friends from Kolkata. I love the city. She was saying that if I didn’t like the city, then we wouldn’t be spending as much time in Kolkata as we do, but I do love the city.

It’s got, in many ways, everything I would look for in a city. Kabul, in a way, was a bit like Kolkata when times were better. This is maybe a replacement for Kabul for me. Kolkata is extraordinary. It’s got that history. It’s got the buildings. Bengalis are fascinating. It’s got culture, fantastic food.

COWEN: The best streets in India, right?

MURPHY: Absolutely.

COWEN: It’s my daughter’s favorite city in India.

MURPHY: Really?

COWEN: Yes.

MURPHY: What does she like about it?

COWEN: There’s a kind of noir feel to it all.

MURPHY: Absolutely.

COWEN: It’s so compelling and so strong and just grabs you, and you feel it on every street, every block. It’s probably still the most intellectual Indian city with the best bookshops, a certain public intellectual life.

MURPHY: It’s widespread. It’s not just elite. It’s everyone. We went to a huge book fair. It’s like going to . . . I don’t know what it’s like going to, Kumbh Mela or something. It’s extraordinary.

There’s a huge tent right in the middle, and it’s for what they call little magazines. Little magazines are these very small publications run by one or two people. They’ll publish poetry. They’ll publish interesting stories. Sadly, I don’t speak Bengali because I’d love to be reading this stuff. There are hundreds of these things. They survive, and people buy them. It’s not just the elite. It’s extraordinary in that way.

COWEN: Is there any significant hardship associated with living there, say a few months of the year?

MURPHY: For us, no. There’s a lot of hardship —

COWEN: No pollution?

MURPHY: Yes. The biggest pollution for me is the noise, the noise pollution.

Interesting throughout.

Inside India’s endless trials

The FT’s Krishn Kaushik covers the courts in India:

…in one recent example a Delhi court concluded a property dispute after 66 years. Both the original litigants were dead. Still, the lawyer for one of the warring parties cautioned that the conclusion was in fact not the end, as the ruling would be appealed.

Three years ago, after pondering a dispute for 16 years, the supreme court sent back a 60-year-old land case for fresh adjudication to a lower court, which had already taken over 30 years to give its judgment in 2006.

A 2021 study [excellent study, AT] of Mumbai real estate found that more than a quarter of the projects under planning or construction and 43 per cent of all “built-up spaces” in the city were under some litigation. My apartment block was one of them.

…One of the reasons for this accumulation is human resources. India has around 16 judges per million people, compared to over 150 for the US. In 2016, the issue brought the country’s chief justice, TS Thakur, to tears during a speech as he requested that the government hire more judges to wade through the “avalanche” of backlog.

Reminds me of one of my favorite MR posts, A Twisted Tale of Rent Control in the Maximum City.

Abundance lacking!

Amtrak is launching a new high-speed Acela train, but there is one wrinkle: It isn’t actually faster, yet.

Five next-generation Acela trains begin service Thursday as part of a $2.45 billion project to improve service along the key Washington-to-Boston corridor. But two of them running from Washington to Boston will actually travel more slowly than their predecessors do on the same route Thursday, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of Amtrak’s schedule. These new trains are scheduled to take at least seven hours and five minutes to complete the trip, compared with the average time of six hours and 56 minutes on the older Acela trains.

Here is more from the WSJ. Via Anecdotal.

Tabarrok on Flight Delays

Tyler already linked to Max’s excellent post on flight delays but Fortune gives you the backstory:

On one sweltering summer afternoon in June, thunderstorms rolled over Boston Logan International Airport. It was the kind of brief, predictable summer squall that East Coasters have learned to ignore, but within hours, the airport completely shut down. Every departure was grounded, and flyers waited hours before they could get on their scheduled flights.

Among those stranded were Maxwell Tabarrok’s parents, in town to help move him into Harvard Business School, where he is completing an economics PhD. Tabarrok told Fortune he was fascinated by how an entire airport could grind to a halt, not because of some catastrophic event, but due to a predictable hiccup rippling through an overstretched system.

So, he did what any good statistician would: dive into the data. After analyzing over 30 years—and 100 gigabytes—of Bureau of Transportation Statistics data, he found out his parents’ situation wasn’t bad luck: Long delays of three hours or more are now four times more common than they were 30 years ago.

Not only that, but Tabarrok found airlines are trying to hide the delays by “padding” the flight times—adding, on average, 20 extra minutes to schedules so a flight that hasn’t gotten any faster still counts as “on time.” Thus, on paper, the on-time performance metrics have improved since 1987, even as actual travel times have gotten longer.

We had a can’t miss appointment the next morning and ended up renting a car and driving through the night from Boston to the Washington. Glad Max got a great post out of it!

Northern Ghana travel notes

You will see termite mounds, baobab trees, and open skies.

The major city is Tamale, the third largest urban settlement in the country. The town is manageable and traffic is not intense. At night it is quiet. The “main street” is just a strip of stuff, and it feels neither like a center of town nor an “edge city” growth. Some of the nearby roads still are not paved. It is a shock to the visitor to realize that the center of town is not going to become any more “center of town-y,” no matter how much you drive around looking for the center of town.

We all liked it.

The “Red Clay” is a series of large art galleries and installations, of spectacular and unexpected quality, just on the edge of Tamale. Some of the installations reminded me of Beuys, for instance the large pile of abandoned WWII stretchers. One also sees there a Polish military plane from the 1930s, an old East German train, and a large pile with tens of thousands of glass green bottles. Some of the galleries have impressive very large paintings by James Barnor, mostly of Ghana workers building out the railroad. Goats wander the premise and scavenge for garbage. If you are an art lover, this place is definitely worth a trip.

The Larabanga mosque does not look as old as internet sources claim. I consider it somewhat overrated?

The surrounding area is 80-90 percent Muslim.

A driver explained to me that Islam in Tamale was very different from Islam in Saudi Arabia, because a) in Ghana women can drive motorbikes, and indeed have to for work, and b) in northern Ghana husbands cannot take any more than four wives.

Many more people here speak English than I was expecting. Some claim that they all speak decent English. I doubt that, but the percentage is way over half.

It all feels quite safe, and furthermore the drivers are not crazy.

Zaina Lodge has a kind of “infinity pool,” at a very modest scale, with views of the forest and sometimes of elephants drinking at the nearby water hole. It is one of the two or three best hotel views I have had.

My poll will grow in size, but so far zero out of two hotel workers use ChatGPT. One had not heard of it. High marginal returns!

Time Theft at the Terminal

Travel expert Gary Leff on the billions in wasted time spent at airports:

Maybe the biggest failure in air travel is something we don’t talk about at all. How is it possible that people are being told to show up at the airport 2.5 to 3 hours before their flight, and that isn’t considered a failure of massive proportions?

As Gary points out airport delay wipes out many technological advancements:

The lengthened times for showing up at the airport mean that it no longer even makes sense for many people to take shorter flights, but aircraft technology (electric, short and vertical takeoff) is changing and becoming far more viable in the coming years…The FAA is considering standards for vertiports but are we thinking creatively enough or will that conversation be too status quo-focused either because of regulator bias or because it’s entrenched interests most involved?

More and smaller airports are needed. Streamlined security, that doesn’t wait for nationwide universal rollout, is needed. We need runways and taxiways and air traffic capacity to increase throughput without stacking delays. Most of all, we need to avoid complacency that accepts the status quo as given.

By the way, Washington Dulles (IAD) has ~10.5 min security waits, among the best in the nation and the world for a big airport but it is terrible at inbound passport control. (Also, I am not a fan of the people movers.)