Category: Uncategorized

Revolving Door Patent Examiners

The revolving door between government and private industry creates opportunities for regulatory capture. Dick Cheney’s moves between Secretary of Defense, CEO of Halliburton and Vice-President certainly raised eyebrows. Secretaries of the Treasury, Robert Rubin, Hank Paulson and Steve Mnuchin were all former bankers at Goldman Sachs. Former members of Congress who become lobbyists are common as are bureaucrats and congressional staffers who turn to lobbying on behalf of the industries they previously regulated. At the same time, it seems desirable that government should be able to draw from top notch people in the private sector and it’s not surprising that private sector firms would want to hire people with government experience. It’s unfortunate (in my view) that government is so entwined with the private sector but that is inevitable in a mixed economy. Nevertheless, it would be useful if we had more data and less anecdote when it comes to the revolving door.

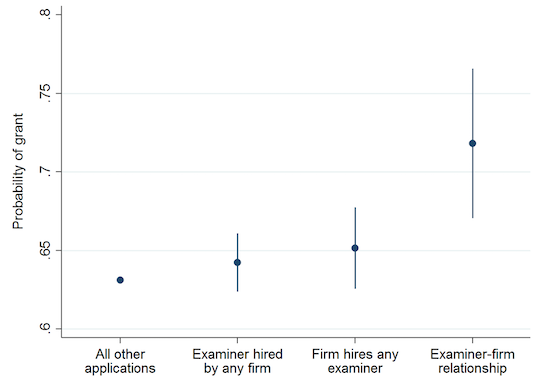

In a new and impressive paper (summary here), Haris Tabakovic and Thomas Wollmann take a detailed look at this issue using patent examiners. Using data on over 1 million patent decisions they find that examiners grant significant more patents to firms that later hire them.

It’s possible that examiners want to work for firms that have high quality patents but several considerations suggest that this is not the explanation for the correlation between grant probability and firm hiring. First, the firms doing the hiring are law firms that handle patent applications. We are not talking about USPTO examiners all wanting to work for Google.

It’s possible that examiners want to work for firms that have high quality patents but several considerations suggest that this is not the explanation for the correlation between grant probability and firm hiring. First, the firms doing the hiring are law firms that handle patent applications. We are not talking about USPTO examiners all wanting to work for Google.

Second, in a very clever analysis the authors show that USPTO examiners who leave for the private sector tend to go to a city near their college alma mater. Moreover, examiners who leave are more likely to approve patents to firms located their alma mater (even when these firms subsequently do not hire them). In other words, it looks as if (on the margin) patent examiners are more generous to firms that they might want to subsequently work for because they are located in places desirable to them. Patent examiners who do not leave do not show a similar bias which removes a home-city boosterism effect. All of these effects are after taking into account examiner fixed effects–so it’s not that examiners who leave are different on average it’s that examiners who leave act differently when firms are located in regions that are potentially desirable to those examiners.

Finally, the authors show that patent quality, as measured by future citations, is lower for patents granted to firms that later hire the examiner or to firms in the same city who are granted patents by the examiner (i.e. to firm-patents the examiner might have given a pass to in order to curry favor). The authors also find some evidence in the patents themselves. Namely, patents that are grant to subsequent employers tend to have claims that are shorter (i.e. stronger) because fewer words were added during the claims process.

The policy implications are less clear. Waiting periods are crude–in other contexts we call these non-compete clauses and most people don’t like them. Note also that these relationships appear to be driven by norms rather than explicit bargaining. USPTO examiners are paid substantially less than their private sector substitutes and that nearly always seems like a bad idea. Paying examiners more would reduce the incentive to rotate.

What is land for Georgist purposes?

Matthew Prewitt wrote this interesting piece “Reimagining Property: A Philosophical Look at Harberger Taxation.” As he defines a Harberger tax, you report the value of your property, pay a tax on that amount, but if you under-report the value someone can buy the property from you at that price. The goal is to encourage turnover of assets, rather than hoarding of assets. Prewitt writes:

Recall that in a world where the natural and artificial components of capital were magically unmixed, we might impose a Harberger tax near the turnover rate on natural capital, and a Harberger tax near zero on artificial capital. But, recognizing that we do not live in such an ideal world, Posner and Weyl propose to set HT rates at varying percentages of the turnover rate for different assets, depending on those assets’ investment elasticities. That is, assets whose value increases more readily with investment should generally enjoy lower HT relative to their turnover rate, to facilitate investment.

…artificial capital is value that emerges in response to incentives…

As time passes, artificial capital starts to resemble natural capital.

Think of a new boat, built yesterday. Now think of the Parthenon. The labor that made the boat can and should be rewarded. It makes sense for the spoils of boat ownership to accrue to its builder. But the labor that made the Parthenon has dissolved into the mists of time. There is no sense rewarding it. We simply find the building in our environment, like an ocean, a mountain, or a nickel deposit. Whoever possess it deserves an incentive for its upkeep, but not a reward for its existence. Any profits from Parthenon ownership ought to be distributed broadly, and not end up in any particular pocket. Thus, unlike the new boat, the Parthenon ought to be treated like natural capital. Yet it is the product of human labor; when erected, it was the very epitome of artificial capital.

Of course there is a decay function in how we treat rights in intellectual property, and this argument suggests there should be a decay function for rights in physical capital as well. After some point in time, that physical capital becomes Georgist land, and thus subject to the efficiencies of the land tax, not to mention possible Harberger taxation.

Prewitt’s conclusion is:

- artificial capital should have a Harberger tax rate near zero

- natural capital should have a Harberger tax near the turnover rate

- artificial capital becomes more like natural capital as more time passes and/or it changes hands more times

More generally, as I suggested about five years ago, the forthcoming fights will be about the taxation of wealth not income.

I wonder, however, if this one shouldn’t be argued in the opposite direction. Let’s say excellence is under-rewarded. If a structure or capital expenditure lasts for a long period of time, maybe that is strongly positive selection and it deserves a subsidy? For one thing, such structures are likely to be iconic brands of a kind, with strong option value and the costs of irreversibility if we let them perish or fall into disrepair. The example of the Parthenon is a useful one, because in fact the monument is endangered by air pollution, and arguably it should receive a larger subsidy for protection, whether for intrinsic reasons or for its economic contribution to Greek tourism.

For the pointer I thank David S.

Thursday assorted links

Does Amazon monopsony lead to higher prices?

A number of you have questioned that point I made yesterday, arguing that a standard monopolist that becomes a monopsonist will restrict output by hiring less labor, for fear of driving up the price of that labor.

I don’t think Amazon has significant monopsony power in many if any labor markets, but it does have some monopsony power over say book publishers. Amazon uses this power to force down book prices and that in turn forces down author advances to some degree. Amazon sells more books and that does mean higher output and lower prices, contrary to what the critics are charging.

Keep in mind also that Amazon is (mostly) a platform company. It’s not their goal to someday put all their competitors out of business and jack up the price of paperbacks to $35. Rather, they seek to flood the market with output, investing in brand name, better data, talent hiring, acquired logistics skills, and so on. To the extent Amazon has monopsony power (again, fairly limited outside of books), they can bargain down costs and flood the market even more, playing into this core strategy, again involving lower rather than higher prices.

America does pretty well at public health

Michael S. Sparer and Anne-Laure Beaussier has a new and interesting piece on this topic, here is part of the abstract:

First, the United States outperforms its European peers on several public health metrics. Second, the United States spends a comparable proportion of its health dollar on prevention. Third, these results are due partly to a federalism twist (while all three nations delegate significant responsibility for public health to local governments, federal officials are more engaged in the United States) and partly to the American version of public health moralism. We also consider the renewed interest in population health, noting why, against expectations, this trend might grow more quickly in the United States than in its European counterparts.

I also learned (or relearned) from this paper the following:

1. For per capita prevention, the U.S. is a clear first in the world. (I wonder, by the way, to what extent this contributes to higher health care costs in the United States, since preventive care also can drive doctor and hospital visits.)

2. The UK and France made a deliberate decision to switch away from public health to curative medicine, after the end of World War II, when they were building out their universal coverage systems.

3. The American history with public health programs is a pretty good one, with advances coming from the anti-smoking campaign, lower speed limits, anti-drunk driving initiatives, fluoridated water, and mandatory vaccination programs.

4. The British fare poorly on various public health metrics.

5. “The US system of public health fares rather well compared to other Western nations.” On net, our population is not as anti-science as it may seem, at least not if we look at final policy results, as compared to some of our peer countries.

All in all, an interesting read.

Intertemporal sushi substitution demand curves slope downward

Jaroslav Bobrowski knows a good deal when he sees one. Accordingly, an all-you-can-eat offer at one sushi restaurant is no longer available to him.

The triathlete follows a special diet in which he fasts for 20-hour periods. So when he does sit down for dinner, he tries to make up for lost time.

But after devouring a staggering 100 plates at the Running Sushi restaurant in Landshut, Germany, as part of its $26 buffet deal, the restaurant declared him persona non grata…

Depending on the serving, a piece of sushi contains, according to fatsecret.com, an average of 40 to 50 calories. This means that Bobrowski could have consumed around 4,000 calories in the one sitting. Eater reported that he may have eaten as much as 18 pounds of sushi.

Bobrowski is 5’7″, weighs 174 pounds and has less than 10 percent body fat.

Here is the full story, via John Chamberlain.

The EU “link tax” has been resurrected

And here is commentary from Ben Thompson:

This is why the so-called “link tax” is doomed to failure — indeed, it has already failed every time it has been attempted. Google, which makes no direct revenue from Google News, will simply stop serving Google News to the EU, or dramatically curtail what it displays, and the only entities that will be harmed — other than EU consumers — are the publications that get traffic from Google News. Again, that is exactly what happened previously.

There is another way to understand the extent to which this proposal is a naked attempt to work against natural market forces: Google’s search engine respects a site’s robot.txt file, wherein a publisher can exclude their site from the company’s index. Were it truly the case that Google was profiting unfairly from the hard word of publishers, then publishers have a readily-accessible tool to make them stop. And yet they don’t, because the reality is that while publishers need Google (and Facebook), that need is not reciprocated. To that end, the only way to characterize money that might flow from Google and Facebook (or a €10-million-in-revenue-generating Stratechery) to publishers is as a redistribution tax, enforced by those that hold the guns.

Here is the full post, excellent as always.

Wednesday assorted links

1. “Shan Tianfang, a Superstar of Chinese Storytelling, Dies at 83.” (NYT) Videos at the link, too.

2. “In fact, there was no evidence that introverts enjoyed solitude more than extraverts. Rather, the most important trait related to liking one’s own company was having strong “dispositional autonomy”. Link here.

4. “A robust data-driven approach identifies four personality types across four large data sets.”

5. India’s singing village, where everyone has their melody.

The rant against Amazon and the rant for Amazon

Wow! It’s unbelievable how hard you are working to deny that monopsony and monopoly type market concentration is causing all all these issues. Do you think it’s easy to compete with Amazon? Think about all the industries amazon just thought about entering and what that did to the share price of incumbents. Do you think Amazon doesn’t use its market clout and brand name to pay people less? Don’t the use the same to extract incentives from politicians? Corporate profits are at record highs as a percent of the economy, how is that maintained? What is your motivation for closing your eyes and denying consolidation? It doesn’t seem that you are being logical.

That is from a Steven Wolf, from the comments. You might levy some justified complaints about Amazon, but this passage packs a remarkable number of fallacies into a very small space.

First, monopsony and monopoly tend to have contrasting or opposite effects. To the extent Amazon is a monopsony, that leads to higher output and lower prices.

Second, if Amazon is knocking out incumbents that may very well be good for consumers. Consumers want to see companies that are hard for others to compete with. Otherwise, they are just getting more of the same.

Third, if you consider markets product line by product line, there are very few sectors where Amazon would appear to have much market power, or a very large share of the overall market for that good or service.

Fourth, Amazon is relatively strong in the book market. Yet if a book is $28 in a regular store, you probably can buy it for $17 on Amazon, or for cheaper yet used, through Amazon.

Fifth, Amazon takes market share from many incumbents (nationwide) but it does not in general “knock out” the labor market infrastructure in most regions. That means Amazon hire labor by paying it more or otherwise offering better working conditions, however much you might wish to complain about them.

Sixth, if you adjust for the nature of intangible capital, and the difference between economic and accounting profit, it is not clear corporate profits have been so remarkably high as of late.

Seventh, if Amazon “extracts” lower taxes and an improved Metro system from the DC area, in return for coming here, that is a net Pareto improvement or in any case at least not obviously objectionable.

Eighth, I did not see the word “ecosystem” in that comment, but Amazon has done a good deal to improve logistics and also cloud computing, to the benefit of many other producers and ultimately consumers. Book authors will just have to live with the new world Amazon has created for them.

And then there is Rana Foroohar:

“If Amazon can see your bank data and assets, [what is to stop them from] selling you a loan at the maximum price they know you are able to pay?” Professor Omarova asks.

How about the fact that you are able to borrow the money somewhere else?

Addendum: A more interesting criticism of Amazon, which you hardly ever hear, is the notion that they are sufficiently dominant in cloud computing that a collapse/sabotage of their presence in that market could be a national security issue. Still, it is not clear what other arrangement could be safer.

Tax salience and the new Trump tariffs

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column. Here is one excerpt:

…tariffs distort consumer decisions more than sales taxes do. It may well be true that consumers don’t notice tariffs as such. But they respond by buying less, lowering their well-being and also possibly lowering GDP and employment.

It gets worse yet. President Donald Trump’s tariffs typically are applied to intermediate goods coming from China, such as circuit boards and LCD screens. The end result is more expensive computers at the retail level. But most consumers see only the higher price for computers. They probably don’t know which intermediate goods Trump put the tariffs on, and for that matter many U.S. consumers probably don’t even know what circuit boards are, much less where they come from.

The end result is that the tariffs are somewhat invisible, or at least they are invisible as tariffs. It’s highly unlikely there will be mass protests against a 10 percent tariff on circuit boards. No one will get “circuit board tariff charge” bill in the mail, as they might with their property taxes, and unlike gasoline, people don’t buy computers very often.

Most generally, it can be said that the new Trump policy makes the high prices salient, but the underlying tariffs not very salient at all. This is the worst possible scenario. The higher prices will reduce consumption and output, yet the invisibility of the tariffs will limit voter pushback.

Do read the whole thing.

Tuesday assorted links

What should Robert Wiblin ask Tyler Cowen?

Robert will be interviewing me later this week, as an installment of Conversations with Tyler, just as Patrick Collison once interviewed me a while back. At least part of the interview will focus on my forthcoming book Stubborn Attachments: A Vision of a Society of Free, Prosperous, and Responsible Individuals. (And we will do 2.5 hours, a Robert specialty!) Here is part of Robert’s bio:

I studied both genetics and economics at the Australian National University (ANU), graduated top of my class and was named Young Alumnus of the Year in 2015.

I worked as a research economist in various Australian Government agencies including the Treasury and Productivity Commission.

I then moved to Oxford in the UK to work at the Centre for Effective Altruism, first as Research Director and then Executive Director.

I then became Research Director for 80,000 Hours. In 2015 the project went through Y Combinator, and in 2016 we moved from Oxford to Berkeley, California in order to grow more quickly.

He is renowned for his thorough preparation and he runs a very good podcast of his own. So what should he ask me?

The future of retail surveillance?

“We learn behaviors of what it looks like to leave,” said Michael Suswal, Standard Cognition’s co-founder and chief operating officer. Trajectory, gaze and speed are especially useful for detecting theft, he said, adding, “If they’re going to steal, their gait is larger, and they’re looking at the door.”

Once the system decides it has detected potential theft behavior, a store attendant will get a text and walk over for “a polite conversation,” Mr. Suswal said.

Here is more from Nellie Bowles at the NYT, via Michelle Dawson.

Ain’t no $20 bills on this Cambridge sidewalk…not any more…

An art installation made up of £1,000 worth of penny coins left in a disused fountain disappeared in just over one day.

The 100,000 pennies were placed in the fountain at Quayside in Cambridge at 08:00 BST on Saturday and were due to be left for 48 hours.

All of the coins were gone by 09:00 BST on Sunday, but the In Your Way project is not treating it as theft.

Artistic director Daniel Pitt said it was “a provocative outcome”.

The work, which used money from an Arts Council England lottery grant, was one of five pieces staged across the city over the weekend.

Cambridge-based artist Anna Brownsted said her fountain piece “was an invitation to respond, a provocation”.

Here is the full story, via Adam, S. Kazan.