Category: Web/Tech

From the comments: on the change in your internet privacy

I am still seeing many misleading headlines and takes on the recent Congressional vote to “sell your internet privacy.” Do read this thread to the bottom (link here):

March 29, 2017 at 9:27 am [edit]

-

-

-

-

The rules that are being changed went into effect january 4th? is that correct?

TC again: If you believe these claims to be wrong, by all means tell us and I will investigate the matter further. But so far I think I am witnessing another case of “Trump exaggerated click-bait headlines” on this one. It is fine if you think this change is a bad idea, but it is hard for me to see it as the internet privacy skies falling, especially if you already are using Google and Facebook. It’s not exactly the case that our privacy birthright has been stolen from us…

Here is further useful perspective from The Washington Post.

-

My new podcast with Ezra Klein

Here is part of Ezra’s description:

I had a simple plan: ask Cowen for his thoughts on as many topics as possible. And I think it worked out pretty well. We discuss everything from New Jersey to high school sports to finding love to smoked trout to nootropics to Thomas Schelling to Ayn Rand to social media to speed reading strategies to happy relationships to the disadvantages of growing up in Manhattan. And believe me when I say that is a small sampling of the topics we cover.

We also talk about Tyler’s new book, “The Complacent Class,” which argues, in true Cowenian fashion, that everything we think we know about the present is wrong, and far from being an age of rapid change and constant risk, we have become a cautious, even stagnant, society.

This as information dense a discussion as I’ve hosted on this podcast. I took a lot away from it, and I think you will too.

Here is the link.

You can calm down about internet service providers selling your browser history

In light of these laws and institutions safeguarding user privacy, members of the House of Representatives need not fear that voting for the joint resolution to rescind the FCC’s privacy rule will mark the end of individual privacy on the Internet.

Here is the full piece by Ryan Radia, via Brent Skorup. He also recommends this longer Georgia Tech paper of broader interest (pdf).

Why might better matching reduce mobility?

Wil Wade emails me some very interesting points:

As someone who has changed jobs a fair amount and recently, I thought I might be able to give some ideas on why better matching and results decreases mobility. Some of these might be fairly easy to set up tests for. (Note I am a programmer, someone with many job prospects in almost anywhere I could want, so salt as desired.)

1. You think you will find something. Everywhere has lots of jobs posted, so if feels like if you just wait until tomorrow, that job in your area will pop up. Why look at another city, when your city posts 100 new jobs a day (none of which will be good for you, but you don’t know that)

2. Perhaps especially in white collar jobs, you never get a job from a job posting. Never is a bit strong, but your network leads to most jobs. (of the 5 jobs I have had in the ~10 years since graduating, three of those were network based) The less mobile your network, the less mobile you can be.

3. Comparisons are really hard to make when cost of living varies so much. I do not know if the variance in cost of living has increased over the past 30 years, but I do know that it feels really high. As a programmer I easily could move to any of the large cities SF, LA, NYC. But the cost of living adjustment is really hard to make. And currently impossible to make at an I could move anywhere level.

Does AI *really* help the defense in military situations?

Christina, an apparent MR reader, asked me whether it is really true that AI helps military defense more than military offense, as was previously argued by Eric Schmidt. I can think of a few parallel cases:

1. In chess, AI clearly has helped the defense. Top computer programs never play 32-move brilliant sacrifice victories against each other, a’ la Mikhail Tal. Most games are drawn, and a victory tends to be long and protracted. (Do note it is sometimes better to get the war over with and lose right away.)

2. In the NBA, analytics have helped offense more, for instance by showing that more attempted shots should be three-pointers. Analytics of course is not AI, but you can consider it a more primitive form of using information technology to improve decisions.

3. It is interesting to ponder the differences between chess and the NBA as potential analogies. In chess, the attack often “plays itself,” as the player with the initiative may be following fairly standard strategies of bringing the Queen and some lesser pieces in the neighborhood of the opposing King, or maybe just capturing material. Finding the correct defense is often a more complex matter, and the higher quality of the chess-playing programs thus boosts defense more than offense. Besides, under perfect information chess is almost certainly a draw, and the use of AI asymptotically approaches that outcome.

In professional basketball, the offense typically has more options and permutations, and given any offensive decisions, the defense often respond in fairly typical fashion, such as lunging at the player attempting a shot, or doubling Stephen Curry as he crosses the half-court line. In those cases where the defense has more options, however, analytics conceivably could help basketball defense more than offense. A (hypothetical) example of this would be using game tape and AI to see which kinds of tugs on the jersey best disrupt the shot or rhythm of the team’s leading scorer. That said, most of the action seems to be in honing the options for the offense.

4. Is warfare more like chess or more like the NBA?

I believe the USA has more options in most of its conflicts, and thus AI will help the United States, at least at first.

In the Second World War the Nazis had more options than their opponents. In the Civil War and American Revolution, however, the available offense was more static and predictable, and AI for those fighting forces might have helped the defense more. In the Iran-Iraq war I suspect the defense had more options too. Terror groups have more meaningful options than the forces defending against terror, and thus AI might help terror groups more than the defense, at least provided they had equal access to the data and to the technology (which is doubtful at this point, still as part of the exercise this is useful).

5. One important qualifier is that the chess and NBA examples already assume a game is on to be played. A war, in contrast, is started as a matter of volition on at least one side. If AI creates a new arms race of sorts, where one side at times opens up a decisive lead, that may provoke more decisions to engage and thus attack. The mere fact that AI increases the variance in the power gap between the two sides may increase the number of attacks and thus wars.

So there is more to this question than meets the eye at first, and I have only begun to engage with it.

Addendum: AI is also spreading in the legal world, will this help defendants or plaintiffs more?

Do online reviews diminish physician authority?

Mostly yes, that is a result for cosmetic surgeons, and that may be one reason why online evaluation of medical services has been relatively slow to evolve in an effective manner. Here is part of the abstract of a new paper:

I argue that surgeons see reviews overwhelmingly as a threat to their reputation, even as actual review content often positively reinforces physician expertise and enhances physician reputation. I show that most online reviews linked to interview participants are positive, according considerable deference to surgeons. Reviews add patients’ embodied and consumer expertise as a circumscribed supplement to surgeons’ technical expertise. Moreover, reviews change the doctor-patient relationship by putting it on display for a larger audience of prospective patients, enabling patients and review platforms to affect physician reputation. Surgeons report changing how they practice to establish and maintain their reputations. This research demonstrates how physician authority in medical consumerist contexts is a product of reputation as well as expertise. Consumerism changes the doctor-patient relationship and makes surgeons feel diminished authority by dint of their reputational vulnerability to online reviews.

Here is the paper, by Alka V. Menon, and the pointer is from the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Can rents in megacities keep on going up forever?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, and it is assuming no major increase in supply in the megacities themselves. Here is one bit:

We live in a special time where clustered activities are unusually important for economic growth. Some activities, such as dentistry and cement production, don’t cluster geographically very much, for obvious reasons. In contrast, finance (New York and London), information technology (the Bay Area), and entertainment (Hollywood and New York) are the most clustered. For whatever reasons, it makes sense to have many of the top decision-makers in one place.

Leading cities have become so expensive in large part because two of these clustering sectors — finance and information technology — have been ascendant. There is no particular reason to expect those trends to continue forever, and that will bind rents in affected cities.

Even tech will decentralize its gains over time:

If you think of a typical technology project, some of the gains go to the venture capitalists and the intellectual property holders, and some of the gains go to broader society, including consumers. Insofar as the gains are disproportionately reaped by the early project initiators, then yes real estate values in the Bay Area (and other tech clusters) will rise. But the most likely future for information technology is that it will spread its benefits more and more broadly into more and sectors of the economy. That scenario suggests a partial convergence of urban futures.

Another way to put the point is that intellectual property returns erode over time. In the early years of smartphones, a big part of the gain goes to Apple. As cheap imitators enter the market, prices fall and more of the gains go to consumers, or business users of the product, who are scattered across the country.

The article contains other points of interest.

Does AI in warfare help the offense or the defense?

…I interviewed Eric Schmidt of Google fame, who has been leading a civilian panel of technologists looking at how the Pentagon can better innovate. He said something I hadn’t heard before, which is that artificial intelligence helps the defense better than the offense. This is because AI always learns, and so constantly monitors patterns of incoming threats. This made me think that the next big war will be more like World War I (when the defense dominated) than World War II (when the offense did).

Here is the link, by Thomas E. Ricks, via Blake Baiers.

Making public goods excludable again

One of Beijing’s busiest public toilets is fighting the scourge of toilet paper theft through the use technology – giving out loo roll only to patrons who use a face scanner.

The automated facial recognition dispenser comes as a response to elderly residents removing large amounts of toilet paper for use at home.

Now, those in need of paper must stand in front of a high-definition camera for three seconds, after removing hats and glasses, before a 60cm ration is released.

Those who come too often will be denied, and everyone must wait nine minutes before they can use the machine again.

But there have already been reports of software malfunctions, forcing users to wait over a minute in some cases, a difficult situation for those in desperate need of a toilet.

The camera and its software have also raised privacy concerns, with some users on social media uneasy about a record of their bathroom use.

Here is the full story, via Michelle Dawson.

Cyber plus nuclear equals Uh-Oh

Cyber weapons are different. If you are a state and you let potential enemies know about your arsenal of cyber attacks, you are giving them the opportunity to fix their information systems so that they can neutralize the threat. This means that it is very hard to use cyber weapons to make credible threats against other states. As soon as you have made a credibly-specific threat, you have likely given your target enough information to figure out the vulnerability that you want to exploit.

This means that offensive cyber weapons are better for gathering intelligence or actually taking out military targets than for making threats. In this regard, they are the opposite of nuclear weapons, which are more useful as threats than as battlefield options. Nuclear weapons can create stability because they deter attacks. In effect, they create a stable system of beliefs where no state wants to seriously attack a nuclear power, for fear that this might lead to a conflict that would escalate all the way to nuclear war.

Nuclear weapons and cyber attacks don’t mix well.

Unfortunately, this means that the advantages of cyber operations become an important liability for nuclear deterrence when they are used for “left of launch” attacks on nuclear launch systems. By secretly penetrating another state’s launch system, you may undermine the stable system of beliefs that discourages an attack.

Consider what might happen in a tense standoff between two states that both have nuclear weapons, where one state has penetrated the other state’s launch system, so that it could stop a nuclear counter attack. The state that has penetrated the launch system knows that it has a military advantage. However, if it reveals the advantage to the target state, the target state will be able to patch its system, destroying the advantage. The target state does not know that it is at a disadvantage, and it cannot be told by the attacker.

The result is that the two states have very different perceptions of the situation. The attacker thinks that there is an imbalance of power, where it has the advantage. The target thinks that there is a balance of power, where both states have nuclear weapons and can deter each other. This means that the first state will be less likely to back down, and might escalate conflict, secure in the knowledge that it can neutralize the other state if necessary. However, the target state may too behave in provocative ways that raise the stakes, since it mistakenly believes that at a certain point the other state will have to back down, for fear of nuclear war. Thus, this creates a situation where each side may be more willing to escalate the tense situation, making it more likely that one state will decide to move toward war.

That is from Eric Gartzke and Jon R. Lindsay, there is more interesting material at the link.

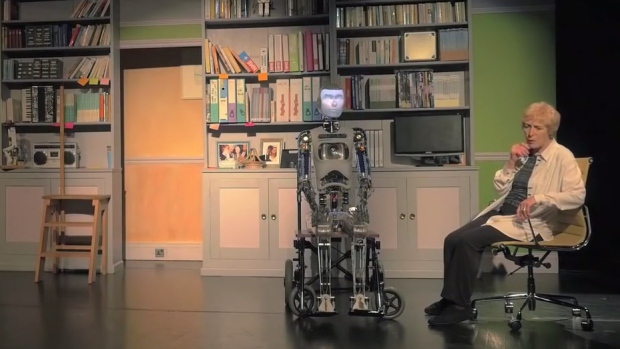

The Robothespian

When Judy Norman walks on stage for the play Spillikin, she performs beside a somewhat different cast member — a humanoid robot.Featuring a “robothespian”, the play brings love and technology together for a story about an engineer who builds a robot to keep his wife company after he dies.

Yet accuracy is required from the human thespian:

The robot is connected to the theatre’s control room, where a laptop transmits cues for its performance.

“[There is] a big pressure on the actor…to always have the right lines, always stand in the right place so that the robot is looking at the right direction at that particular moment,” Welch said.

Onstage, Norman talks to the robot and even kisses it. In return, the robot replies, displays facial expressions and moves its hands.

Here is the full story, with more photos and video, via Michelle Dawson.

The Devil is in the Details

That is the title of a recent paper in the Journal of Development Economics (NBER version here, 2013 ungated version here), and although the piece does not feel dramatic at first it is one of my favorite articles of the year. It pins down some critical features of economic underdevelopment better than any study I know. The subtitle, by the way, is “The Successes and Limitations of Bureaucratic Reform in India,” the authors are Iqbal Dhaliwal and Rema Hanna, and the work is set in rural Karnataka.

It is not easy to excerpt from, so I will summarize the narrative:

1. Using biometric technology — thumbprints — to monitor absenteeism induces staff attendance for public health workers to rise by almost 15 percent.

2. That in turn leads to a reduction in low-birth weight babies.

3. Yet the government proved not so interested in monitoring attendance on a more regular basis, not even to enforce their pre-existing human resource policies. Potential penalties against late or absent doctors were not, for the most part, enforced.

4. Following the implementation of monitoring, the doctors showed the least improvement in attendance of all the workers, in fact virtually no improvement. The entire positive effect came from nurses, lab technicians, and lower level staff.

5. The government was reluctant to continue the monitoring because it feared staff attrition and staff discord, especially from the doctors. There is growing private sector demand for doctors, and many doctors are considering leaving these clinics for superior pay elsewhere, and perhaps also superior location. Therefore the doctors are given, de facto, a very lenient absence and lateness policy, in lieu of a pay hike.

6. It is already the case that many of these doctors moonlight on the side, or have separate private practices, and that spending more time at the public clinic is not their major priority.

7. It is not easy for the underfunded local government to pay these doctors more, and thus a high level of lateness and absenteeism continues. I wonder also what would be the morale costs on the non-doctors, if the monitoring were to be continued to be enforced in this differential manner over a longer period of time.

Has creative destruction become more destructive?

John Komlos has a new paper on this topic, here is the abstract:

Schumpeter’s concept of creative destruction as the engine of capitalist development is well-known. However, that the destructive part of creative destruction is a social and economic cost and therefore biases our estimate of the impact of the innovation on GDP is hardly acknowledged, with the notable exception of Witt (1996.“Innovations, Externalities and the Problem of Economic Progress.” Public Choice 89:113 –30). Admittedly, during the First and Second Industrial Revolutions the magnitude of the destructive component of innovation was no doubt small compared to the net value added to GDP. However, we conjecture that recently the destructive component of innovations has increased relative to the size of the creative component as the new technologies are often creating products which are close substitutes for the ones they replace whose value depreciates substantially in the process of destruction. Consequently, the contribution of recent innovations to GDP is likely upwardly biased. This note calls for further research in innovation economics in order to measure and decompose the effects of innovations into their creative and destructive components in order to provide improved estimates of their contribution to GDP and to employment.

Think of Uber being a relatively close substitute for taxicabs, for instance. Speculative, as they say, and the paper does not in fact actually demonstrate these conclusions, but at least we should be asking such questions more often.

Should we tax robots?

That idea was suggested recently by Bill Gates, though I think you can debate with what degree of literalness. It’s worth a ponder in any case, and here is a recent Noah Smith column on the idea, and here is Summers in the FT, WaPo link here. And here is Izabella Kaminska.

Put aside the revenue-raising issue (which will require some taxes on capital, most likely, including on robots): if we have taken in optimal revenue, is there a separate and additional argument for an additional robot tax? In this context, I would consider “robots” to be capital that is especially substitutable for human labor.

Presumably the claim is that there is either a distributional or an “externalities from a happy human being” reason to slow the rate at which capital is substituted for labor. But if we accept that assumption, should we tax robots or subsidize wage labor?

One reason not to tax the robots is that employers might substitute away from robots and toward natural resources rather than toward domestic human labor. Maybe that doesn’t sound intuitive, but think of paying the energy costs to outsource to another nation and transport the outputs back home.

But the main issue is probably one of incidence. A general problem with a wage subsidy is that sometimes much of its value its captured by employers. For instance if the subsidy takes an EITC form, employers could pay less to their workers, but perhaps many eager workers still would seek the job to capture the somewhat higher net total wage, namely the employer portion plus the benefit. If enough workers are keen to get the pay, employers can claw back much of the EITC boost and still get the work force they need.

Now consider the incidence of a tax on robots. If the elasticity of the demand for robots is high, there will be a big shift away from robots and toward labor (and land and other resources). It is at least possible that workers capture more of the gains this way than from the direct subsidy to their wages. On the downside, the employer fares less well under this scheme.

So it depends on how labor and robot elasticities relate to each other. I don’t know what relationship between the parameter values is likely, but typically in these scenarios just about any result is possible. The robot tax would seem to do best when the elasticity of demand for robots is high, but the corresponding elasticity of demand for labor is low (and differentials in supply elasticities do not offset this). As robots and labor become more substitutable, that difference in demand elasticities is likely to diminish. So if you are going to do this, maybe it is necessary to do it soon, precisely when it does not seem needed.

Your call, but that is the basic set-up of the problem.

Global trade Danish shipping company fact of the day

Maersk had found that a single container could require stamps and approvals from as many as 30 people, including customs, tax officials and health authorities.

While the containers themselves can be loaded on a ship in a matter of minutes, a container can be held up in port for days because a piece of paper goes missing, while the goods inside spoil. The cost of moving and keeping track of all this paperwork often equals the cost of physically moving the container around the world.

That is by Nathaniel Popper and Steve Lohr, mostly about blockchains, via Ángel Cabrera.

Something is not quite adding up here. According to Ars Technica, this vote replaces a rule that hasnt even taken affect yet. :

https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2017/03/how-isps-can-sell-your-web-history-and-how-to-stop-them/

“So what has changed for Internet users? In one sense, nothing changed this week, because the requirement to obtain customer consent before sharing or selling data is not scheduled to take effect until at least December 4, 2017. ISPs didn’t have to follow the rules yesterday or the day before, and they won’t ever have to follow them if the rules are eliminated.”

Im not saying this vote is a good thing, but it sounds to me like all the things we fear are already possible.