Is the Volcker rule a good idea?

Treasury Secretary Jacob J. Lew has strongly urged federal agencies to finish writing the Volcker Rule by the end of the year — more than a year after they had been expected to do so — and President Obama recently stressed the importance of the deadline.

By the way, five (!) agencies are writing the rule, which is not a good sign. As for the Volcker rule more generally, here are a few points:

1. If restricting activity X makes large banks smaller, that will ease the resolution process, following a financial crack-up. That is a definite plus, although we do not know how much easier resolution will be.

2. It is not clear that banning bank proprietary trading will lower the chance of such a financial crack-up. The overall recent record of real estate lending is not a good one, and as Edward Conard pointed out, restricting banks to the long side of transactions is not obviously a good idea. I do see the moral hazard issue with allowing banks to engage in the potentially risky activity of proprietary trading. Still, so far the data are suggesting that the banks which cracked up during the crisis did so because of overconfidence and hubris, not because of moral hazard problems (i.e., they still were holding lots of the assets they otherwise might have been trying to “game”).

3. There is no strong connection between proprietary trading and our recent financial crises.

3b. Today the bugaboo is “big banks” but once it was “small banks” and for a while “insufficiently diversified banks.” Maybe it really is big banks, looking forward, or maybe we just don’t know. Small banks have their problems too.

4. There is some chance that proprietary trading will be pushed to a more dangerous, harder to regulate corner of our financial institutions.

5. There is some danger that loopholes in the regulation itself — especially as concerns permissible client activities — may undercut the original intent of the regulation. This will depend on exactly how well the regulation is written, but past regulatory history does not make me especially confident here. And the distinction between “speculation” and “hedging” cannot be clearly defined. Should we be writing rules whose central distinctions may be arbitrary? And yet CEOs will have to sign off on compliance (with 950 pp. of regulations) personally. Is that a good use of CEO attention? Here is a good FT piece about how hard (and ambiguous) it will be to enforce the rule globally.

6. I do not myself shed too many tears over the “these markets will become less liquid without banks’ participation” critique, but I would note this is a personal judgment and the scientific status of such a claim remains unclear.

7. Many people, even seasoned commentators, approach the Volcker rule with mood affiliation, starting with how much we should resent our banks or our regulators or how we should join virtually any fight against either “big banks” or regulators. I see many analyses of this issue which spend most of their time on “mood affiliation wind-up,” as I call it, and not so much time on the actual evidence, which is inconclusive to say the least.

8. We still seem unwilling to take actions which would transparently raise the price of credit to homeowners. We instead prefer actions which appear to raise no one’s price of credit and which are extremely non-transparent in their final effects. You can think of the Volcker rule as another entry in this sequence of ongoing choices. That should serve as a warning sign of sorts, and arguably that is a more important truth than the case either for or against the rule.

When I add up all of these factors, I come closer to a “don’t do the Volcker rule” stance in my mind. The case for the rule puts a good deal of stress on #1, but overall it does not fit the textbook model of good regulation. I probably have a more negative opinion of “an extreme willingness to experiment with arbitrary regulatory stabs” than do most of the rule’s supporters, and that difference of opinion is perhaps what divides us, rather than any argument about financial regulation per se.

I really do see how the Volcker rule might work out just fine or even to our advantage. I also see the temptation of arguing “I am against big banks, this is the legislation against big banks which is on the table, so I am going to support it.” But let us at least present to our public audiences just how weak is the evidence-based case for doing this.

Addendum: You will find a different point of view from Simon Johnson here. Here is a counter to his claim that prop trading losses were significant in 2008: “Loan losses didn’t just dwarf trading losses in absolute terms. Loan losses as a share of banks’ total loan portfolios also exceeded trading losses as a share of banks’ trading accounts. Yet no one’s arguing banks should stop lending in order to protect depositors (and rightly so). In short, those expecting the Volcker Rule to be a fix-all for Wall Street’s ills have probably misplaced their hope—the rule seems like a solution desperately seeking a problem.”

The sequester really was a good idea

Here is the latest:

House and Senate negotiators were putting the finishing touches Sunday on what would be the first successful budget accord since 2011, when the battle over a soaring national debt first paralyzed Washington.

I have not seen enough detail to judge this emerging deal, but it seems it will reverse some of the initial cuts to discretionary spending from the sequester. You will recall my original take on the sequester, namely that it brought some much needed spending reductions (relative to baseline, they are mostly not actual spending reductions!), and that undesirable side effects could be handled by a subsequent Coasian bargain between the parties. (And here is me on the macro consequences of the sequester, and there was also plenty of monetary offset.) That appears to be exactly what is in progress. It is unlikely that bargain will approximate an ideal, but the pre-sequester spending decisions were not ideal either.

China/Hong Kong markets in everything

Rich mainland parents are paying thousands of Hong Kong dollars to private investigators to spy on their children studying in Hong Kong, including PhD students and kindergarteners.

Four detective agencies said they handled on average “a few” to “a dozen” week-long investigations for mainland parents every month.

“The number has more than doubled compared to a few years ago,” said Kar Liu, a private eye at Wan King On Investigations.

Philic Man Hin-nam, founder and director of Global Investigation and Security Consultancy, an all-woman detective agency, said that mainland student cases accounted for about 40 per cent of the more than 100 requests made by parents last summer for information on their children.

The majority of family cases were instigated by Hong Kong parents who had reason to fear their children were involved with drugs or being led astray.

“Many mainland students studying in Hong Kong are single children from rich families,” Liu of Wan King On Investigations said. “Those parents attach great importance to their children’s behaviour.”

…Typically, a team of three agents monitor a student, taking photos and reporting back to parents daily.

There is more here, via Mark Thorson.

The potential for the anti-Nazi music detector in contemporary German culture

Saxony State Police in Germany have developed a smartphone application that can identify neo-Nazi lyrics and racist words in rock songs. Der Spiegel reported Tuesday that German interior ministers will meet this week to discuss whether to implement this new method of policing.

The government said that neo-Nazi music helps radical organizations recruit youth, and it is used as a type of gateway drug to bring in new conscripts. The application, nicknamed “Nazi Shazam,” can identify names of songs just by playing a small sample of a song. The application would allow the police to react instantly if far-right songs are played on radio stations, at concerts, in club nights or at demonstrations.

There is much more here, hat tip goes to MT. This is of course another method of surveillance and measurement of our tastes, and some version of this idea will be picked up by marketers, whether or not this particular example is adopted.

Assorted links

1. The occasional upward-sloping demand curve.

2. The top ten martial arts movies (but where is Drunken Master 2 on the list?).

3. Will birds take out Amazon delivery drones? And is music streaming going to die?

4. What does a planned Palestinian city look like?

What is the evidence on quantitative easing?

From the comments, Stephen Williamson quotes/writes:

“…but it’s not nearly a close enough engagement with the evidence, which does pretty clearly show some short-run effects [from QE] are still operating, even if those effects are diminishing with time.”

I’d be curious to know what “evidence” it is that “clearly” shows this. My guess is you’re making this up.

In the first part he is quoting me, the “I’d be curious” paragraph is his own words. Overall, I would say here that the word “guess” is an accurate, albeit unfortunate description of how he is assessing the relevant evidence.

The background story is that Steve is arguing that QE should be deflationary rather than expansionary. What does the evidence say?

Here are Krishnamurthy and Vissing-Jorgensen on the United States (pdf):

…evidence from inflation swap rates and TIPS show that expected inflation increased due to both QE1 and QE2…

On Japan, here are Girardin and Moussa:

…we propose new empirical evidence supporting the ability of quantitative easing to provide stimulation to both output and prices.

Or try Joyce, Miles, Scott, and Vayanos, from The Economic Journal:

…a growing literature has begun to provide estimates of the macroeconomic effects. In one of the first studies of this nature, Baumeister and Benati (2010) estimate a time-varying parameter structural VAR to investigate the macroeconomic impact of lower long-term bond spreads during the 2007–09 recession period. In all, the countries they analyse – the US, Euro area, Japan and the UK – they find a compression in the long-term yield spread exerts a powerful effect on both output growth and inflation and their counterfactual simulations indicate that unconventional monetary policy actions in the US and UK averted significant risks both of deflation and of output collapses.

p.F285 of that paper discusses some other literature in detail, again indicating that QE increases the rate of price inflation. This piece is also useful for showing how empirical studies of QE provide decent evidence for asset segmentation and “preferred habitat” theories of bond markets (which responds to another of Steve’s points).

Or try Chung, et.al. from the Fed (since published in the JMCB):

…we find that the asset purchases have probably prevented the U.S. economy from falling into deflation.

This is all consistent with the observation from Scott Sumner:

For God’s sake the dollar fell by 6 cents against the euro on the day QE1 was announced! Does anyone seriously think a 6 cent depreciation in the dollar is deflationary?

There is plenty of (justified) debate as to how strong these effects are, and we all know the difficulties of doing proper empirical work in macroeconomics, and on top of that the time to produce research means these papers are not analyzing the very latest data. But I cannot find a serious — or for that matter non-serious — empirical study suggesting that QE is deflationary in its impact.

Addendum: David Glasner makes a very good point: “…if Williamson’s analysis is correct, the immediate once and for all changes should have been reflected in increased measured rates of inflation even though inflation expectations were falling. So it seems to me that the empirical fact of observed declines in the rate of inflation that motivates Williamson’s analysis turns out to be inconsistent with the implications of his analysis.”

The legacy of Michael Bloomberg

During his tenure, the zoning rules for 37 per cent of the city were changed to permit redevelopment by the private sector, and work on some of the biggest projects is just getting started as he prepares to leave office at the end of this month.

“He is going to define the city for the next 25 years,” said Mitchell L Moss, a professor of urban policy and planning at New York University, and a campaign adviser to Mr Bloomberg in 2001. “It doesn’t matter who the next mayors are. They are still going to be attending groundbreakings for projects he started,” he said.

Much of this development is along the waterfront, which Bloomberg calls “the sixth borough.” There is more here, and the pointer is from Paul Romer.

Assorted links

1. Why the minimum wage doesn’t explain stagnant wages.

2. What is the optimal way to pro-rate co-authorship?

3. White and Asian per capita incomes, in South Africa, are up significantly since Mandela’s election victory in 1994.

4. Innovation changes everything, by Seth Roberts.

5. What kind of ads should a Eugene Fama story carry?

6. The increasing inequality of art prices, and from the story I liked this line: “The beauty of art is that there is a lot of it.”

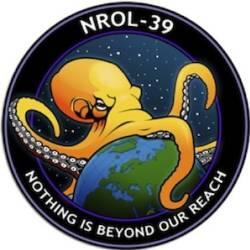

Not From the Onion-NROL 39

The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) launched a new spy-satellite, NROL-39, on Dec. 5. When I first saw this I felt sure it couldn’t be real, it must be from The Onion but no, this is the official logo for the satellite which you can see on the rocket and in this NRO press release.

When the history of how the United States became a dystopian, surveillance state is written no one will be able to say that we were not warned.

Ferguson and Steinetz on Israeli two-year budgets

…longer-term budgets have important advantages. They reduce uncertainty for the ministries, agencies and private companies that depend on government funds. Public investment in infrastructure is a good example; so are defense contracts. In each case, long-term engagements need to be made with contractors and the results take years to materialize. But the danger always exists of unexpected budget cuts that terminate unfinished projects at high cost to all concerned.

A more subtle advantage of longer-term budgets derives from the argument of the Nobel laureates Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott that rules are often preferable to discretion in the realm of economic policy.

…America’s fiscal problems will not be solved without some bipartisan agreement. Biennial budgets might just be the place to start. After all, this is an idea that was supported not just by Ronald Reagan and both Bushes, but also by Bill Clinton, Al Gore (leader in 1993 of the National Performance Review) and the current Treasury secretary, Jacob Lew.

Moreover, Israel’s experience has been a great advertisement. Not only did it enjoy an impressively rapid recovery from the financial crisis under the system of biennial budgets; more remarkably, when directors-general of Israel’s government ministries were polled in 2010, not one of them favored returning to what one called “the Dark Ages and the madness of the single-year budget.”

The NYT Op-Ed is here. If you would like to read a criticism of the two-year budget, try this:

“There is no other country that has a dual-year budget. Why? Because it requires long forecasts,” Ben-Bassat told The Jerusalem Post on Monday.

The predictions for economic growth and tax collection for the past year’s budget were made two-and-a-half years earlier, in the summer of 2010. Simply put, Ben-Bassat says, “they were wrong. Very wrong.”

Ben-Bassat noted that although Israel’s hearty growth started consistently declining in the second quarter of 2011, the old estimates were not revised because of the inflexible budget.

“It doesn’t make sense for policymakers to tie their own hands,” he said. “The finance minister said he wanted to give certainty to the private sector, but he provided just the opposite. It actually created uncertainty.”

You will find another criticism here. You will note that the American states have been moving away from biennial budgets, partly because their revenues have grown more volatile. Connecticut however uses a bifurcated system, where smaller agencies are on a two-year cycle. In Washington state, the government enacts annual revisions to a biennial cycle (pdf). In other words, the available space of options here is quite complex.

Overall I would not press a button to make this change happen. That said, we Americans have not exactly been pivoting on a dime, with optimal changes in fiscal policy, in response to new economic data.

Health care loses jobs (not)

Man bites dog, but this time it is good news, sort of:

For just over 10 years—121 straight months—there was one constant in the monthly jobs report: Health care jobs would go up.

Not anymore.

Health care lost 2,500 jobs in September, the Bureau of Labor Statistics concluded in estimates released last month. And if that number stands, it would be the first net loss for the sector since July 2003.

That is from Dan Diamond.

Addendum: Revising the revision, the BLS now tells us that health care did not lose jobs after all. Dog bites man, once again, though this time with duller teeth.

Assorted links

1. Ted Gioia’s 100 best albums of 2013. Ted understands the acoustical nature of music, and the creation of alternative sound worlds, better than any other music critic I read. Someone constructed a playlist from Ted’s picks here. And The Economist picks best books of the year. It is the best “best books” list so far this year.

2. Does GPS interfere with our internal mental maps?

3. Can you build a political party around the moral superiority of eunuchs?

4. Phasing in minimum wage hikes.

5. The winning essays on the “Cowen vs. Mokyr” theme, I think they are very good.

6. Matt Zwolinski defends the guaranteed annual income idea.

The happiness of economists

There is a new paper by Lars P. Feld, Sarah Necker, and Bruno S. Frey, and here is the abstract:

This study investigates the determinants of economists’ life satisfaction. The analysis is based on a survey of professional, mostly academic economists from European countries and beyond. We find that certain features of economists’ professional situation influence their well-being. Happiness is increased by having more research time while the lack of a tenured position decreases satisfaction in particular if the contract expires in the near future or cannot be extended. Surprisingly, publication success has no effect on satisfaction. While the perceived level of external pressure also has no impact, the perceived change of pressure in recent years has. Economists may have accepted a high level of pressure when entering academia but do not seem to be willing to cope with the increase observed in recent years.

You will note that “Economists tend to report a high level of life satisfaction.” Furthermore this does not vary by gender. Here are the nationality effects:

Compared to German economists, Italian, French and researchers from Eastern European countries have a statistically significantly lower probability to report being “highly satisfied” (significant at least at the 5%-level). A similar effect is observed for economists from Spain, Portugal, and Austria; the effects are, however, at most significant at the 10%-level. Researchers from Switzerland, North America and Scandinavian countries tend to be more happy.

For the pointer I thank Viktor Brech.

Academic boycotts of Israel

One of them is gathering steam (and more detail here):

The National Council of the American Studies Association announced Wednesday that it has unanimously endorsed a boycott of Israeli universities and other Israeli institutions — and urged its members to vote to make the boycott official policy of the association.

The move by the council, even if awaiting approval by the membership, is seen as a major victory for the movement for an academic boycott of Israel.

And yet I have a better idea. If one is going to boycott institutions of Israel, should one not also boycott strong, powerful nations which have supported much of what Israel has done, especially strong, powerful nations which stole a lot of land from the original inhabitants, refuse to give it back, and have recently practiced torture, aggressive military intervention, and the murder of innocent civilians, and which spy upon much of the world, mostly without apology?

That’s right, they might consider boycotting the United States, starting with their very own name, which now would read “Council of the Studies Association.” Cynical advocates of “self-deportation” (I am not one of them) might suggest a more general boycott of the nation as it relates to their choices of residence and employment, but I will settle for the group boycotting academic conferences in America.

I am in in Tel Aviv — albeit briefly — and happy to be here. I am reminded of David Brooks’s recent column on the creeping politicization of life. That is one trend we all ought to oppose.

Addendum: Here is a good dissent from the boycott.

The rising star system for scientific achievement and collaboration

This is taken from an NBER paper by Ajay Agrawal, John McHale, and Alexander Oettl. Here is the Inside Higher Ed summary:

A study (abstract available here) being released today suggests that it may be coming from a broader range of academic departments, but from a smaller number of elite scientists…

The analysis is based on a look at the top-ranked departments and the top scientists (as judged by output of citation-weighted papers) in evolutionary biology from 1980 through 2000. The research found two apparently contradictory trends:

- The share of citation-weighted publications produced by the top 20 percent of departments fell from approximately 75 percent to 60 percent.

- The share of papers produced by the top 20 percent of individual scientists increased from 70 percent to 80 percent.

In other words, the role of the individual star became more important at a time that the role of the star department (while still significant) fell.

There is not only more collaboration, but collaborations are taking place across a wider range of “quality” of institutions:

And the average distance in rank of institutional departments increased as well. In 1980, it was about 30 (meaning someone at an institution ranked 20th, say, was collaborating with someone at an institution ranked 50th). By 2005, the average rank gap was 55.

I see a common trend at mid-tier universities to care less about the research quality of the average faculty member, and care more about the quality and reputation of the stars, while “marketing” those stars more intensely than before. And there are many more good researchers at lower-tier institutions, but they may not command much of a premium in terms of pay or working conditions. Their specialized knowledge can make them very valuable as co-authors on the right project and so they end up in some high quality collaborations.