Basil Halperin on the job market from MIT

Here is the home page, here is his job market paper (with Daniele Caratelli) “Optimal policy under menu costs”:

We analytically characterize optimal monetary policy in a multisector economy with menu costs, and show that inflation and output should move inversely after sectoral shocks. That is, following negative shocks, inflation should be allowed to rise, and vice versa. In a baseline parameterization, optimal policy stabilizes nominal wages. This nominal wage targeting contrasts with inflation targeting, the optimal policy prescribed by the textbook New Keynesian model in which firms are permitted to adjust their prices only randomly and exogenously. The key intuition is that stabilizing inflation causes shocks to spill over across sectors, needlessly increasing the number of firms that must pay the fixed cost of price adjustment compared to optimal policy. Finally, we show in a quantitative model that, following a sectoral shock, nominal wage targeting reduces the welfare loss arising from menu costs by 81% compared to inflation targeting.

Noteworthy!

Apple Ad From 1999

Thursday assorted links

1. Maxims from Larry Gagosian.

2. How might California regulate AI?

3. Why has growth in medical knowledge been so stagnant? Northwestern job market paper by Megumi Murakami.

4. My AI webinar for Macmillan. And also from Macmillan here is an Eric Parsons profile video.

5. Are Singaporean couples who are funny more satisfied with each other?

6. Pakistan starts to expel 1.7 million undocumented Afghani migrants. That is perhaps the largest forced expulsion since the 1950s?

7. Paul’s latest (video). And the song itself.

What should I ask Fuchsia Dunlop?

Yes I will be doing a third (!) Conversation with her. She has written some of the best books and cooked some of the best food. Here is her Wikipedia page. Here is her home page.

Here is her new book — self-recommending if anything was — Invitation to a Banquet: The Story of Chinese Food.

Here is my previous podcast with Fuchsia, and here is my first podcast with her. This time around — what should I ask?

Marriage sentences to ponder

Increased exposure to opposite-sex members of other class groups generates a substantial increase in interclass marriage, but increased exposure to other race groups has no detectable effect on interracial marriage.

That is from the job market paper of Benjamin Goldman, a job market candidate from Harvard University.

My excellent Conversation with Stephen Jennings

Recorded in Tatu City, Kenya, not far from Nairobi, Tatu City is a budding Special Enterprise Zone. Here is the transcript, audio, and video. Here is the episode overview:

Stephen and Tyler first met over thirty years ago while working on economic reforms in New Zealand. With a distinguished career that transitioned from the New Zealand Treasury to significant ventures in emerging economies, Stephen now focuses on developing new urban landscapes across Africa as the founder and CEO of Rendeavour.

Tyler sat down with Stephen in Tatu City, one of his multi-use developments just north of Nairobi, where they discussed why he’s optimistic about Kenya in particular, why so many African cities appear to have low agglomeration externalities, how Tatu City regulates cars and designs for transportation, how his experience as reformer and privatizer informed the way utilities are provided, what will set the city apart aesthetically, why talent is the biggest constraint he faces, how Nairobi should fix its traffic problems, what variable best tracks Kenyan unity, what the country should do to boost agricultural productivity, the economic prospects for New Zealand, how playing rugby influenced his approach to the world, how living in Kenya has changed him, what he will learn next, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Just give us some basic facts. Where is Tatu City right now, and where will it be headed when it’s more or less finished?

JENNINGS: Tatu City is the only operational special economic zone [SEZ] in the country. It is 5,000 hectares of fully planned urban development. It is at quite an advanced stage. We have 70 large-scale industrial companies with us, including major multinationals and many of the regional leaders. We have 3,000 students come on site every day to our four new schools. We’re advanced in building the first phase of the first new CBD for the region. We have tens of thousands of core center jobs moving into that area, together with other modern office amenities. All of the elements — we have many residential modules, thousands of new residential units at a wide range of price points — all of the elements of a new city are in place.

COWEN: How many people will end up living here?

JENNINGS: Around 250,000.

COWEN: And how many businesses?

JENNINGS: There’ll be thousands of businesses.

And delving more deeply into matters:

COWEN: What do you think is the book [on economic development] that has influenced you most?

JENNINGS: It’s a very good question. I think I’ve read just about everything in development. There’s nothing I really like very much. Development is a black box. I don’t think there’s anything that has much predictive power. There’s a lot of ex post explanations, whether they be policy settings, location, culture. I think 90% of them are ex post; very few of them are predictive. Some of them are just tautologies. I really like factualization.

It’s descriptive more than analytical, but it just makes it clear that most of the world has been on a very similar development trajectory. It’s just not sequenced. Sweden started early; Ethiopia started late. But the nature of the transition and the inevitability of that transition, other than very extreme circumstances, is kind of the same.

COWEN: What do you think economists get wrong?

JENNINGS: I don’t think we really understand development at all, because if we could, we could predict it. We can predict virtually nothing. It’s just too complicated. It’s too connected with politics. I think there’s a lot of feedback loops and elements of development that we don’t understand properly. We certainly can’t quantify them because the development’s happening in such a wide range of settings, from communism dictatorships through to very liberal systems and with all different kinds of industrial — on every dimension, there’s a huge range of variables.

Excellent and interesting throughout.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Jake Seliger on the clinical trial system, from the point of view of a patient. And from his wife Bess Stillman.

2. The war in Sudan, and its economics.

3. Progress on the dengue front (link corrected).

4. Joy Buchanan review of GOAT.

5. Zvi’s review of the AI Executive Order, recommended if you care.

Why aren’t the American hostages receiving more attention?

Yesterday Senator Marsha Blackburn tweeted: “The White House admitted Hamas is holding nearly 500 Americans hostage in Gaza.” To be clear, those are Americans not allowed to leave Gaza (NYT), they are not being held in a compound. As for hostages in the narrower sense of that term, there seem to be about ten. Neither are instances of liberty, nor are they safe positions to be in. Personally, I would consider both groups to be hostages.

No matter which definition of hostage you prefer, I don’t see so many major MSM articles about these hostages. I remember the much earlier Iranian hostage crisis, when many Americans even knew the identities and life stories of individual hostages. It was a front page item almost every day. As I am composing this post (the day before), I don’t see it on the NYT front page at all. Same with WaPo, though they do have “Biden hosts Trick or Treaters at the White House.” If you consider this New Yorker story, well yes it covers the American hostages somewhat, but it is nothing close to what I might have expected. They are not even the article lead. So why so little coverage? I have a few candidate hypotheses, which may or may not be true:

1. The MSM wants Biden’s reelection, and they don’t want him ending up painted as “another Jimmy Carter” who cannot rescue the hostages.

2. The young Woke staffers at MSM don’t want to make Hamas look too bad, or to make the Israeli retaliation look too good.

3. These hostages are themselves not “The Current Thing,” even though the war itself seems to be The Current Thing. Has “The Current Thing” become so narrowly circumscribed?

4. For some national security reasons, MSM has been told by our government that too much hostage coverage would endanger their possible release or rescue.

5. The Biden administration is pressuring MSM not to cover the hostages too much, out of fear that the domestic pressures for America to intervene will become too strong.

6. It simply hasn’t happened yet, due to noise in the system.

What else? I am not saying any of those are true, and some of them are more conspiratorial than the kinds of explanation I usually find persuasive. So why don’t the American hostages receive more attention?

The Burial

I loved The Burial on Amazon Prime. Not because it’s a great movie but because it serves as a cinematic representation of my academic paper with Eric Helland, Race, Poverty, and American Tort Awards. Be warned—this isn’t a spoiler-free discussion, but the plot points are largely predictable.

The Burial is a legal drama based on real events starring Jamie Foxx as Willie Gary, a flashy personal injury lawyer who takes the case of Jeremiah O’Keefe, a staid funeral home operator played by Tommy Lee Jones. O’Keefe is suing a Canadian conglomerate over a contract dispute and he hires Gary because he’s suing in a majority black district where Gary has been extremely successful at bringing cases (always black clients against big corporations).

The Burial is a legal drama based on real events starring Jamie Foxx as Willie Gary, a flashy personal injury lawyer who takes the case of Jeremiah O’Keefe, a staid funeral home operator played by Tommy Lee Jones. O’Keefe is suing a Canadian conglomerate over a contract dispute and he hires Gary because he’s suing in a majority black district where Gary has been extremely successful at bringing cases (always black clients against big corporations).

As a drama, I’d rate the film a B-. The major failing is the implausible friendship between the young, black, flamboyant Willie Gary and the older, white subdued Jeremiah O’Keefe. Frankly, the pair lack chemistry and the viewer is left puzzled about the foundation of their friendship. The standout performance belongs to Jurnee Smollett, who excels as the whip-smart opposing counsel.

What makes The Burial interesting, however, is that it tells two stories about Willie Gary and the lawsuits. The veneer is that Gary is a crusading lawyer who uncovers abuse to bring justice. Most reviews review the veneer. Hence we are told this is a David versus Goliath story, a Rousing True Story and a story about the “dogged pursuit of justice.” The veneer is there to appease the simple minded, an interpretation solidified by The Telegraph which writes, without hint of irony:

The audience at the showing was basically adult and they applauded at the end which you often see in children’s movies but rarely in adult films.

The real story is that Gary is a huckster who wins cases in poor, black districts using a combination of racial resentment and homespun black-church preaching to persuade juries to redistribute the wealth from out-of-state big corporations to local knuckleheads. I use the latter term without approbation. Indeed, Gary says as much in his opening trial where he persuades the jury to give his “drunk”, “tanked” “wasted”, “no-good”, “depressed,” “suicidal” client, $75 million dollars for being hit by a truck! Why award damages against the corporation? Because, “they got the bank.” (He adds that his client had a green light–this is obviously a lie. Use your common sense.)

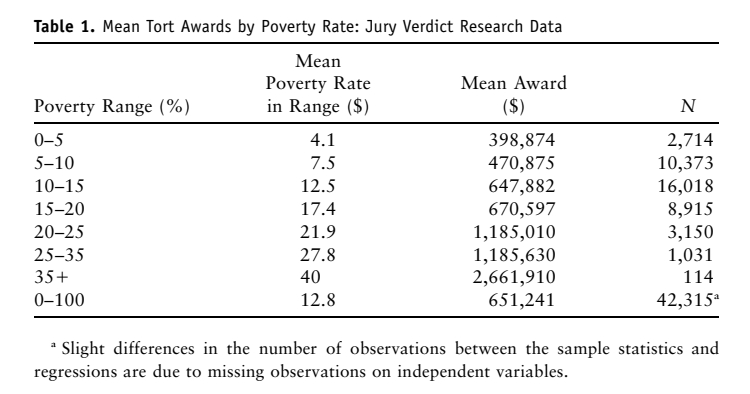

My paper with Helland, Race, Poverty, and American Tort Awards, finds that tort awards during this period were indeed much higher in counties with lots of poverty, especially black poverty. We find, for example, that the average tort award in a county with 0-5% poverty was $398 thousand but rose to a whopping $2.6 million in counties with poverty rates of 35% or greater! The Burial is very open about all of this. The movie goes out of its way to explain, for example, that 2/3rds of the population of Hinds county, the county in which the trial will take place, is black and that is why Willie Gary is hired.

My paper with Helland, Race, Poverty, and American Tort Awards, finds that tort awards during this period were indeed much higher in counties with lots of poverty, especially black poverty. We find, for example, that the average tort award in a county with 0-5% poverty was $398 thousand but rose to a whopping $2.6 million in counties with poverty rates of 35% or greater! The Burial is very open about all of this. The movie goes out of its way to explain, for example, that 2/3rds of the population of Hinds county, the county in which the trial will take place, is black and that is why Willie Gary is hired.

The case on which the movie turns is as absurd as the opening teaser about the drunk, suicidal no-good who collects $75 million. Indeed, the two trials parallel one another. The funeral home conglomerate, the Loewen group, offered to buy three of O’Keefe’s funeral homes but after shaking on a deal they didn’t sign the contract. That’s it. That’s the dispute. The whole premise is bizarre as Loewen could have walked away at any time. Moreover, O’Keefe claims huge damages–$100 million!–when it’s obvious that O’Keefe’s entire failing business isn’t worth anywhere near as much. So why the large claim of damages? Have you not being paying attention? Because the Loewen group, “they got the bank.”

Furthermore, and in parallel with the earlier case, it’s O’Keefe who is the no-gooder. O’Keefe’s business is failing because he has taken money from burial insurance premiums–money that didn’t belong to him and that should have been invested conservatively to pay out awards–and lost it all in a high-risk venture run by a scam artist. Negligence at best and potential fraud at worst. Moreover, in a strange scene motivated by what actually happened, O’Keefe agrees to sell to Loewen only if he gets to keep a monopoly on the burial insurance market. Thus, it’s O’Keefe who is the one scheming to maintain high prices.

Indeed, the whole point of both of Gary’s cases is that he is such a great lawyer that he can win huge awards even for no-good clients. As if this wasn’t obvious enough, there is an extended discussion of Willie Gary’s hero….the great Johnnie Cochran, most famous for getting a murderer set free.

Loewen should have won the case easily on summary judgment but, of course, [spoiler alert!] the charismatic Gary wows the judge and the jury with entirely irrelevant tales of racial resentment and envy. The jury eats it up and reward O’Keefe with $100 million in compensatory damages and $400 million in punitive damages! The awards are entirely without reason or merit. The awards drive the noble Canadians of the Loewen group out of business.

The Burial is a courtroom drama surfaced with only the thinnest of veneers to let the credulous walk away feeling that justice was done. But for anyone with willing eyes, the interplay of racism, poverty, and resentment is truthfully presented and the resulting miscarriage of justice is plain to see. I enjoyed it.

Addendum: My legal commentary pertains only to the case as presented in the movie although in that respect the movie hews reasonably close to the facts.

Argentina fact of the day

Argentina just released birth statistics for 2022, and the TFR just keeps on dropping. Last year it reached a new record low of 1.36 children per woman. Some provinces have already reched the ultra low levels common in Spain. https://t.co/ZWI4qzkIco

— Birth Gauge (@BirthGauge) October 31, 2023

Denmark takes forceful measures to integrate immigrants

After they fled Iran decades ago, Nasrin Bahrampour and her husband settled in a bright public housing apartment overlooking the university city of Aarhus, Denmark. They filled it with potted plants, family photographs and Persian carpets, and raised two children there.

Now they are being forced to leave their home under a government program that effectively mandates integration in certain low-income neighborhoods where many “non-Western” immigrants live.

In practice, that means thousands of apartments will be demolished, sold to private investors or replaced with new housing catering to wealthier (and often nonimmigrant) residents, to increase the social mix.

The Danish news media has called the program “the biggest social experiment of this century.” Critics say it is “social policy with a bulldozer.”

The government says the plan is meant to dismantle “parallel societies” — which officials describe as segregated enclaves where immigrants do not participate in the wider society or learn Danish, even as they benefit from the country’s generous welfare system.

Here is more from the NYT, and do note that Singapore has its own version of this policy. I would make a few observations:

1. Putting aside the normative, analyzing the effects of such policies will be increasingly important. Economists are not especially well-suited to do this, nor is anyone else. I am well aware of the Chetty “Moving to Opportunity” results. That is good work, but a) it probably doesn’t apply to coercive Danish resettlements, and b) cultural context is likely important for the results. At least for the countries that migrants wish to move to, most will have their own versions of this dilemma.

2. “Open Borders” as a sustainable political equilibrium is looking much weaker than it did a month ago. The key question in immigration policy is not “how many migrants should we take in?” (a lot, I would say), but rather “how can we make continuing immigration a politically sustainable proposition?” Many immigration advocates are in a fog about their inability to offer better answers to that question.

3. Will this Danish action, once the entire political economy is worked through, increase or decrease the allowed number of migrants to the country? Looking at the demand side to migrate, will this policy end up attracting a higher or lower quality of migrants to Denmark? Is Denmark even attractive enough as a destination to get away with this? Or will it send a better signal to would-be migrants and thus raise quality?

I would not be too confident about my answers to those questions, nor should you be so confident.

Agustin Lebron on the new AI Executive Order (from my email)

Even though it’s not a compute cap (just a requirement to register, for now), surely this emboldens competitors to OpenAI/etc? If I think I can build a system up to the cap, then my playing field just got more level.

This will also spur lots of research into sample efficiency again, which IMO is a very good thing. It’s been a research area that has languished for years under the “just throw more flops at it” regime.

Finally, I think the order perversely legitimizes capabilities research by showing the world “Well, the US gov’t thinks capabilities are SO important they’re making orders about it”. More attention, more dollars, more progress.

Overall this is accelerative for AI/AGI IMO.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Some comments on the AI Executive Order. And on the role of HHS. And Adam Thierer. And yet another negative take. I agree with the general perspective of the more negative takes, but perhaps they are overrating the legality/enforcement of the actual Order?

2. Acapulco report.

4. New paper on the economic recovery of Hiroshima (Princeton job market paper also).

5. Shocker: university faculty are very slow to adopt generative AI, students are way ahead of them.

Narrative Bending Chart of the Day

From an excellent piece by John Burn-Murdoch in the FT on education and wages in England.

Are dementia rates falling?

A study published in 2020, which drew together multiple pieces of research to track the health of almost 50,000 over-65s, showed the incidence rate of new cases of dementia in Europe and North America had dropped 13 per cent per decade over the past 25 years — a decline that was consistent across all the studies.

For Albert Hofman, who chairs the department of epidemiology at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, the research points to one conclusion: “The absolute risk [of developing dementia] is lower now” than it was 30 years ago. Now, there are early signs that the same phenomenon may be emerging in Japan, a striking development in one of the world’s most aged populations, suggesting that the downward trend is becoming more widespread…

While emphasising that the reasons for the reduction in incidence are not yet fully understood, Hofman believes better cardiovascular health is likely to be a significant factor given the proven links between the two.

Here is more from Sarah Neville at the FT. Maybe that is where the Flynn effect has been hiding!