What is going wrong with American higher education?

Yes, yes all the Woke and PC stuff, but let us also look into the matter more deeply, as in my latest Bloomberg column. There is a serious talent drain due to excess bureaucratization, among other issues:

Another problem is the ongoing mental health crisis among America’s youth. This is not the fault of universities, to be clear, but a lot of unhappy students make for a less enjoyable college experience. The warm glow that so many baby boomers associate with their college years may not be reproduced by the current generation. They might instead look back on a quite troubled time, and in turn have less school loyalty.

I have also observed (as have many of my colleagues) that students seem to have more absences, excuses and missed assignments. No matter what the causes of those developments, they make it harder to run an effective university.

In fact, many of the smartest young people I know are deciding against a career in academia, even if that was their initial intent. They see too much bureaucracy and not enough time for the academic work itself. Students in the biosciences, at least the ones I talk to, seem to be an exception, perhaps because the opportunities to change the world are so obvious.

In my own field, economics, the prospect of having to do a “pre-doc” and then six years for a Ph.D. is driving away creative talent. On the research side, there is an obsession with finding the correct empirical techniques for causal inference. Initially a merited and beneficial development, this approach is becoming an intellectual straitjacket. There are too many papers focusing on a suitably narrow topic to make the causal inference defensible, rather than trying to answer broader, more useful but also more difficult questions.

…As committee obligations, paperwork and referee reports accumulate, the idea that academia allows you to be in charge of your own time seems ever more distant. Bureaucratization is eating away at the free time of professors. Much of the glamour of the job is gone, and my fear is that the system increasingly attracts conformists.

And don’t forget this disaggregation:

There are also big differences within universities. I have been a professor for more than three decades and speak often at other campuses. My impression is that presidents, provosts and deans are relatively sane, if only because they face real trade-offs as they draw up budgets, raise money and make payroll. University staff or student groups, on the other hand, often have no sense of the underlying constraints, and so advocate for ideas and practices that lead to some ridiculous stories. The actual decision makers are frequently not strong enough to push back, so they accept the demands as a way to survive or even advance.

Recommended.

*Rise*

Applications are now open for Rise! Rise is a global initiative that finds brilliant people who need opportunity and supports them for life as they work to serve others and build a better world. The program starts at ages 15–17 and offers Global Winners access to benefits including need-based scholarships, a fully-funded residential summit, mentorship, career development, potential funding, and more. Applications are open until January 25, 2023.

Wednesday assorted links

1. ChatGPT and Bing will be integrated. And Large Language Models as corporate lobbyists.

2. “German is a very ‘spank me’ language,” she tells a Melbourne woman struggling pronounce a porcelain manufacturer’s name. “Königliche,” the woman coughs. Standing beside a handwritten chart of tableware terminology, Ms. Ho trills with delight: “You got it! See? You think ‘spank me,’ immediately you got it.” (NYT link). What in the heck was that article about? Cracking cultural codes perhaps?

3. The “stay at home girlfriend” trend.

4. How much are Russian cyberattacks diminishing?

5. The published meta-study on lead and crime updates the results somewhat, in line with my expectations.

Privatization Improves Airports

Laurent Belsie summarizes a new NBER paper, All Clear for Takeoff: Evidence from Airports on the Effects of Infrastructure Privatization:

When private equity funds buy airports from governments, the number of airlines and routes served increases, operating income rises, and the customer experience improves.

…As of 2020, nearly 20 percent of the world’s airports had been privatized. Private equity (PE), usually through dedicated infrastructure funds, is playing an increasing role in privatization, purchasing 102 airports out of a total of 437 that have ever been privatized.

…A key metric of airport efficiency is passengers per flight. The more customers an airport can serve with existing runways and gates, the more services it can deliver and the more earnings it can generate. When PE funds buy government-owned airports, the number of passengers per flight rises an average 20 percent. There’s no such increase when non-PE private firms acquire an airport. Overall passenger traffic rises under both types of private ownership, but the rise at PE-owned airports, 84 percent, is four times greater than that at non-PE-owned private airports. Freight volumes and the number of flights, other measures of efficiency, show a similar pattern. Evidence from satellite image data indicates that PE owners increase terminal size and the number of gates. This capacity expansion helps enable the volume increases and points to the airport having been financially constrained under previous ownership.

…PE firms tend to attract new low-cost carriers to their airports, which in turn may lead to greater competition and offer consumers better service and lower prices. With regard to routes, PE acquirers increase the number of new routes, especially international routes, more than other buyers. International passengers are often the most profitable airport users, especially in developing countries.

A PE acquisition is also associated with a decline in flight cancellations and an increase in the likelihood of receiving a quality award. When an airport shifts from non-PE private to PE ownership, its odds of winning an award rise by 6 percentage points. The average chance of winning such an award is just 2 percent.

The fees that airports charge to airlines rise after airport privatizations. When the buyer is a PE firm, there is also a push to deregulate government limits on those fees. For example, after three Australian airports were privatized in the mid-1990s, the price caps governing airport revenues were replaced with a system of price monitoring that allows the government to step in if fees or revenues become excessive.

The net effect of a PE acquisition is a rough doubling of an airport’s operating income, due mostly to higher revenues from airlines and retailers in the terminal rather than cost-cutting. The driving forces behind these improvements appear to be new management strategies, which likely includes greater compensation for managers, alongside investments in new capacity as well as better passenger services and technology.

My reading program for the half-year to come

To be clear, I very much like Lex Fridman’s proposed reading list, and I hope to reread many of those books. Most of them are much deeper than their sometimes reputations, I might add. (For all the stupid whining about the list, odd that no one is asking why he doesn’t read more in Russian.)

If you are curious, here is what I have planned for the first half of the year to come:

1. Review copies that come my way — considerable numbers of them are great! And thank you all for sending.

2. Reading or rereading through the works of Jonathan Swift, for a paper I am writing. The topic is Swift on state-church relations, and as relates to some points from Rene Girard, and Swift on science, as it relates to Peter Thiel.

3. The history of American comedy and stand-up, as relates to a future CWT with Noam Dworman.

4. What is recommended to me by credible others, throughout the course of the year.

5. Many books in Indian history, for the 1600-1800 period, give or take, to prep for a likely CWT with William Dalrymple.

6. Reread and re-study of the New Testament, for CWTs with Tom Holland and David Bentley Hart. And for its own sake too.

7. More British and Irish history, from all eras. That will mean reading in clusters, rather than obsessing over particular volumes. Lately I’ve been reading about British cultural and architectural heritage issues, in part to get a different and more advanced bead on YIMBY-NIMBY conflicts, and also to relearn British history through the history of its major buildings.

8. Haldor Laxness and Jon Fosse are among the classic novels in my queue, neither would be a reread. And I will start the new Javier Marías that comes out in English, it takes me too long in Spanish. Twentieth century Polish poetry, and more on the Polish history of ideas and literature. And I’ve vowed to read more museum catalogs (more picture books!). In German I will try Goethe’s Dichtung und Wahrheit, reread some Rilke, some Tuschel, and maybe some more Herta Müller.

9. Other stuff too, most of all what I buy spontaneously. Just yesterday Deepti Kapoor’s Age of Vice arrived at the house. There is some Eugene Volodazkin on the way.

10. I’ve been reading a good deal lately about neural nets, transformers, and other AI-related topics, but not understanding it very well. YouTube videos have helped only a little. We’ll see if I ramp up those efforts or discard them. I am learning a lot from playing around with GPT, however, and maybe I’ll ask it what else I should read.

Beware the dangers of crypto regulation

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one bit:

No matter how strong the temptation, we should not overregulate.

Begin with two central facts. First, there are numerous ways for small and large investors to lose their money, including by investing in risky equities. Regulating crypto won’t end that danger. Second, despite being one of the largest financial frauds in history, FTX has not created systemic financial risk, which should be the main concern of regulators. And market forces already have made the risk from crypto much smaller: At the peak of crypto values in late 2021, crypto assets had a total value of about $2 trillion; as of this writing, that figure is about $845 billion.

And:

Crypto regulation is not easy to do well. If crypto institutions are treated like regular depository institutions, requiring heavy layers of capital and lots of legal staffing, crypto innovation is likely to dwindle. Such innovation has been more the province of eccentric geniuses than of mainstream regulated institutions. It is hard to imagine Satoshi Nakamoto or Vitalik Buterin at Goldman Sachs.

And what exactly should be the goal of crypto regulation? To make stablecoins truly stable in nominal value? Is that even possible? Or to encourage market participants to see those assets as inherently fluctuating in value?

Neither academic research nor market experience offers clear answers. With systemic risk currently low, perhaps it is better to wait and learn more before moving ahead with regulation. And on a purely practical level, very few members of Congress (or their staff members) have a good working knowledge of crypto and all of its current wrinkles and innovations.

There is much more of value at the link.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Age distribution of CWT guests.

2. ChatGPT and coding. And an explanation of transformers. And another guide here. And chat bot vs. the doctors.

3. Sopranos actor finds $10 million Guercino.

4. Richard Hanania defends Canadian euthanasia.

5. Are enrollments up at faith-based colleges?

6. Major new art and photography museum coming soon to Bangalore.

Why do so many prices end with 99 cents?

Firms arguably price at 99-ending prices because of left-digit bias—the tendency of consumers to perceive a $4.99 as much lower than a $5.00. Analysis of retail scanner data on 3500 products sold by 25 US chains provides robust support for this explanation. I structurally estimate the magnitude of left-digit bias and find that consumers respond to a 1-cent increase from a 99-ending price as if it were more than a 20-cent increase. Next, I solve a portable model of optimal pricing given left-digit biased demand. I use this model and other pricing procedures to estimate the level of left-digit bias retailers perceive when making their pricing decisions. While all retailers respond to left-digit bias by using 99-ending prices, their behavior is consistently at odds with the demand they face. Firms price as if the bias were much smaller than it is, and their pricing is more consistent with heuristics and rule-of-thumb than with optimization given the structure of demand. I calculate that retailers forgo 1 to 4 percent of potential gross profits due to this coarse response to left-digit bias.

That is from a forthcoming paper by Avner Strulov-Shlain. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

What should I ask Glenn Loury?

I will be doing a Conversation with him. So what should I ask?

Retrospective look at rapid Covid testing

To be clear, I still favor rapid Covid tests, and I believe we were intolerably slow to get these underway. The benefits far exceed the costs, and did earlier on in the pandemic as well.

That said, with a number of pandemic retrospectives underway, here is part of mine. I don’t think the strong case for those tests came close to panning out.

I had raised some initial doubts in my podcasts with Paul Romer and also with Glen Weyl, mostly about the risk of an inadequate demand to take such tests. I believe that such doubts have been validated.

Ideally what you want asymptomatic people in high-risk positions taking the tests on a frequent basis, and, if they become Covid-positive, learning they are infectious before symptoms set in (remember when the FDA basically shut down Curative for giving tests to the asymptomatic? Criminal). And then isolating themselves. We had some of that. But far more often I witnessed:

1. People with symptoms taking the tests to confirm they had Covid. Nothing wrong with that, but it leads to a minimal gain, since in so many cases it was pretty clear without the test.

2. Various institutions requiring tests for meet-ups and the like. These tests would catch some but not all cases, and the event still would turn into a spreader event, albeit at a probably lower level than otherwise would have been the case.

3. Nervous Nellies taking the test in low-risk situations mainly to reassure themselves and others. Again, no problems there but not the highest value use either.

So the prospects for mass rapid testing — done in the most efficacious manner — were I think overrated.

I recall the summer of 2022 in Ireland, which by the way is when I caught Covid (I was fine, though decided to spend an extra week in Ireland rather than risk infecting my plane mates). Rapid tests were available everywhere, and at much lower prices than in the United States. Better than not! But what really seemed to make the difference was vaccines. The availability of all those tests did not do so much to prevent Covid from spreading like a wildfire during that Irish summer. Fortunately, deaths rose but did not skyrocket.

The well-known Society for Healthcare Epidemiology just recommended that hospitals stop testing asymptomatic patients for Covid. You may or may not agree, but that is a sign of how much status testing has lost.

Some commentators argue there are more false negatives on the rapid tests with Omicron than with earlier strains. I haven’t seen proof of this claim, but it is itself noteworthy that we still are not sure how good the tests are currently. That too reflects a lower status for testing.

Again, on a cost-benefit basis I’m all for such testing! But I’ve been lowering my estimate of its efficacy.

Wealth across the generations

“The main takeaways:

- Millennials are roughly equal in wealth per capita to Baby Boomers and Gen X at the same age.

- Gen X is currently much wealthier than Boomers were at the same age: about $100,000 per capita or 18% greater

- Wealth has declined significantly in 2022, but the hasn’t affected Millennials very much since they have very little wealth in the stock market (real estate is by far their largest wealth category)”

That is from Jeremy Horpendahl (no double indent performed by me), via Rich Dewey.

Monday assorted links

2. The smartest person that Garett Jones has ever met (short video).

3. “Because increasing the capital-intensity of R&D accelerates the investments that make scientists and engineers more productive, our work suggests that AI-augmented R&D has the potential to speed up technological change and economic growth.” Link here.

4. Predictions from 1923 about 2023.

5. GPT takes the bar exam. And how well do GPTs write scientific abstracts?

6 “The fact that we failed to notice 99.999% of life on Earth until a few years ago is unsettling and has implications for Mars.” The article has other interesting points about the political economy of funding a Mars program. Recommended, and it will make you a space skeptic.

Kindle sale for *Talent*

$2.99, buy here, not sure how long that price is good for. I thank Tom Jackson for the pointer.

Alas, Bennett McCallum has passed away

He was a great monetary and macro economist, and among his many achievements he was a pioneer of ngdp targeting ideas…RIP…

Does Angi Recommend Occupational Licensing?

Peter Blair and Mischa Fisher have a clever new paper on occupational licensing that uses data on millions of leads generated by Angi’s HomeAdivsor. Consumers on HomeAdvisor search for services, the platform knows whether the service requires a license in the consumer’s state and attempts to match the consumer with an appropriate local provider, the local provider can then choose whether to accept or reject the lead. If a lead is accepted, the consumer and provider then negotiate on the price and services–as the negotiation is mostly handled offline, the main measure of interest is the probability a lead is accepted.

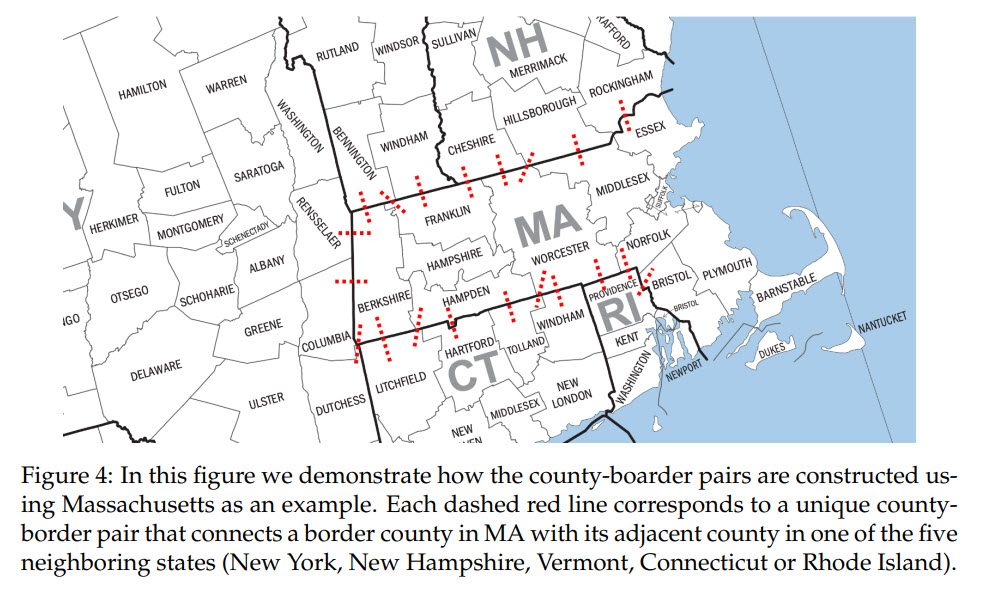

Many occupations are licensed in one state but not in another (as I pointed out in my talk on occupational licensing to the Heritage Foundation this is odd if you think there are strong arguments for occupational licensing on safety or quality grounds). Thus the authors compare the accepted lead rate in states that require a license to complete a task to the rate in states where the same task is unlicensed. To better control for other factors, the authors only compare the accepted lead rate in counties that border different states, as shown below. The authors also control for state, month and task fixed effects.

The bottom line is that the accepted lead rate is 12.3 percentage points or 21% lower in a county/state that license an occupation/task compared to a similar county/state where the task is unlicensed. In other words, if you live in a state that requires a license to complete a task it’s considerable more difficult to find a contractor than if you lived in nearby state that does not license the task.

Not surprisingly, the authors find that the accept rate declines not because there is a surge in demand for the licensed service but because supply declines when there are fewer licensed providers. In the long run, we also know that prices rise in licensed industries (e.g. my paper with Pizzola on licensing in the funeral services industry).

The authors combine their cross-sectional study with an event study that shows that after New Jersey required a license for pool contractors it become more difficult to find a pool contractor in New Jersey relative to other states.

The authors conclude:

The existing literature on licensing on digital platforms, which consists of three other papers, has carefully measured the impact of licensing on consumer satisfaction and safety by demonstrating that customer self-reports of service quality and objective platform measures of service provider safety do not increase in the presence of licensed service providers, despite the positive impact of licensing on prices (Hall et al., 2019; Farronato et al., 2020; Deyo, 2022).

…Taken together, our findings and those from the three others papers studying licensing in digital labor markets indicate that the traditional view of licensing espoused in Friedman (1962) about licensing in offline markets, i.e, licensing is a labor market restriction with limited benefits, also holds in digital labor markets (Hall et al., 2019; Farronato et al., 2020; Deyo, 2022). Our work provides a clear example where labor market regulations developed to govern the analogy economy work against the efficiency gains that technological innovation promises to bring in a digital economy (Goldfarb et al., 2015).