“Unveiling the Price of Obscenity”

Does legitimating sinful activities have a cost? This paper examines the relationship between housing demand and overt prostitution in Amsterdam. In our empirical design, we exploit the spatial discontinuity in the location of brothel windows created by canals, combined with a policy that forcibly closed some of the windows near these canals. To pin down their effect on housing prices, we apply a difference-in-discontinuity (DiD) estimator, which controls for the precise location of brothel windows and the effect of other policies and local developments. Our results show that the housing prices are discontinuous at the bordering canals, and this discontinuity nearly disappears after closures. The discontinuity is also found to decrease with the distance to brothels, disappearing after 300 yards. Our estimates indicate that homes right next to sex workers were 30 percent cheaper before the closures. This result seems unrelated to the presence of other businesses, such as bars and cannabis shops. Instead, the price discount is partly explained by petty crimes. However, 73 percent of the effect remains unexplained after controlling for many forms of crime and risk perception. Our findings suggest that households tend to be against the visible presence of sex workers and related nuisances, reaffirming their marginalization.

That is from a new paper by Erasmo Giambona and Rafael P. Ribas, via a highly reputable man.

Ngi Hamba Mabuse

By Dorothy Masuka.

Saturday assorted links

2. Chat with historical figures, 20,000 of them. When will they do economists? And using GPT for therapy, how do you think it did? People preferred the GPT, until they found out they were speaking with a machine.

3. What some top chess players won in prize money.

4. Claims about quantum computing.

5. Rasheed Griffith on where to eat in Panama.

6. “The use of a longitudinal database of Famine immigrants who initially settled in New York and Brooklyn indicates that the Famine Irish had far more occupational mobility than previously recognized. Only 25 percent of men ended their working careers in low-wage, unskilled labor; 44 percent ended up in white-collar occupations of one kind or another—primarily running saloons, groceries, and other small businesses.” Link here.

GPT and my own career trajectory

For any given output, I suspect fewer people will read my work. You don’t have to think the GPTs can copy me, but at the very least lots of potential readers will be playing around with GPT in lieu of doing other things, including reading me. After all, I already would prefer to “read GPT” than to read most of you. I also can give it orders more easily. At some point, GPT may substitute directly for some of my writings as well, but that conclusion is not required for what follows.

I expect I will invest more in personal talks, face to face, and also “charisma.” Why not?

Well-known, established writers will be able to “ride it out” for long enough, if they so choose. There are enough other older people who still care what they think, as named individuals, and that will not change until an entire generational turnover has taken place.

I expect the entire calculus here is very different for someone who is twenty years old, and I hope to write more on that soon.

Today, those who learn how to use GPT and related products will be significantly more productive. They will lead integrated small teams to produce the next influential “big thing” in learning and also in media. Most current contributors will miss that train almost entirely, just as so many people missed the importance of the internet for learning and also for media. But we still don’t know how important this “next big thing” will be, for instance, compared to YouTube.

In the short run, using GPT for ideas and inspiration will be more important than using it for copy. Like blogging, I am happy when people attack it, because that raises the moat surrounding it.

Overall the trajectory of change is very difficult to predict, as are the forthcoming technological developments themselves.

How long does a Roman emperor last for?

Of the 69 rulers of the unified Roman Empire, from Augustus (d. 14 CE) to Theodosius (d. 395 CE), 62% suffered violent death. This has been known for a while, if not quantitatively at least qualitatively. What is not known, however, and has never been examined is the time-to-violent-death of Roman emperors. This work adopts the statistical tools of survival data analysis to an unlikely population, Roman emperors, and it examines a particular event in their rule, not unlike the focus of reliability engineering, but instead of their time-to-failure, their time-to-violent-death. We investigate the temporal signature of this seemingly haphazardous stochastic process that is the violent death of a Roman emperor, and we examine whether there is some structure underlying the randomness in this process or not. Nonparametric and parametric results show that: (i) emperors faced a significantly high risk of violent death in the first year of their rule, which is reminiscent of infant mortality in reliability engineering; (ii) their risk of violent death further increased after 12 years, which is reminiscent of wear-out period in reliability engineering; (iii) their failure rate displayed a bathtub-like curve, similar to that of a host of mechanical engineering items and electronic components. Results also showed that the stochastic process underlying the violent deaths of emperors is remarkably well captured by a (mixture) Weibull distribution.

That is from a new paper by Joseph Homer Saleh. Via Patrick Moloney. And here are new results on why Roman concrete was so much more durable than the emperors.

What should I ask Noam Dworman?

I will be doing a Conversation with him. Noam is the owner of Comedy Cellar, considered by many to be the world’s best comedy club, located in Greenwich Village, NYC. There is a branch in Las Vegas too. The Cellar also has its own TV show.

Here is Norm’s LinkedIn page. Noam also makes music in a band, usually playing guitar.

So what should I ask him?

Friday assorted links

1. More Scott Sumner movie reviews.

2. “Why do they hate the children?” Hat tip @pmarca.

3. Apple unveils AI-voiced audiobooks. And some insights into how ChatGPT models work. And can ChatGPT do analogical reasoning without explicit training?

4. Is Garett Jones channeling the Lord of the Vineyard?

5. Self-perceived attractiveness reduces face mask-wearing intention.

6. 41% of NYC school students were chronically absent last year.

7. Was Vermeer a Jesuit? And it seems he may have used a camera obscura.

Herbert Gintis has passed away, RIP

ChatGPT and the revenge of history

I have been posing it many questions about Jonathan Swift, Adam Smith, and the Bible. Chat does very well in all those areas, and rarely hallucinates. Is it because those are settled, well-established texts, with none of the drama “still in action”?

I suspect Chat is a boon for the historian and the historian of ideas. You can ask Chat about obscure Swift pamphlets and it knows more about them than Google does, or Wikipedia does, by a long mile. Presumably it “reads” them for you?

When I ask about current economists or public intellectuals, however, more errors creep in. Hallucinations become common rather than rare. The most common hallucination I find is that Chat invents co-authorships and conference co-sponsorships like crazy. If you ask it about two living people, and whether they have worked together, the fantasy life version will be rather active, maybe fifty percent of the time?

Presumably that bug will be fixed, but still it seems that for the time being Chat has shifted some real intellectual heft back in antiquarian directions. Perhaps it is harder for statistical estimation to predict words about events that are still going on?

Here are some tips for using ChatGPT.

Of course Chat is already a part of my regular research and learning routine. Woe be unto those who cannot or do not use it effectively! I feel sorry for them, get with the program people…

David Wallace-Wells on the pandemic

Rather than quote the parts where he says nice things about Alex and me, how about a wee excerpt on the GBD crowd:

Dr. Bhattacharya, for instance, proclaimed in The Wall Street Journal in March 2020 that Covid-19 was only one-tenth as deadly as the flu. In January 2021 he wrote an opinion essay for the Indian publication The Print suggesting that the majority of the country had acquired natural immunity from infection already and warning that a mass vaccination program would do more harm than good for people already infected. Shortly thereafter, the country’s brutal Delta wave killed perhaps several million Indians. In May 2020, Dr. Gupta suggested that the virus might kill around five in 10,000 people it infected, when the true figure in a naïve population was about one in 100 or 200, and that Covid was “on its way out” in Britain. At that point, it had killed about 45,000 Britons, and it would go on to kill about 170,000 more. The following year, Dr. Bhattacharya and Dr. Kulldorff together made the same point about the disease in the United States — that the pandemic was “on its way out” — on a day when the American death toll was approaching 600,000. Today it is 1.1 million and growing.

It has fallen down the memory hole a bit just how um…”off” these people were, and that is the polite word. That said, I don’t think they should have been banned from any social media platforms. Here is the full NYT piece, excellent throughout, and mostly about other topics. For the pointer I thank Alex T.

Thursday assorted links

Shruti Rajagopalan and Janhavi Nilekani podcast

In this episode, Shruti speaks with [the excellent] Janhavi Nilekani about India’s high rate of C-sections compared with vaginal births, problems with maternal healthcare, the present and future of Indian midwifery and much more. Nilekani is the founder and chair of the Aastrika Foundation, which seeks to promote a future in which every woman is treated with respect and dignity during childbirth, and the right treatment is provided at the right time. She is a development economist by training and now works in the field of maternal health. She obtained her Ph.D. in public policy from Harvard and holds a 2010 B.A., cum laude, in economics and international studies from Yale.

Here is the link.

Is America suffering a ‘social recession’?

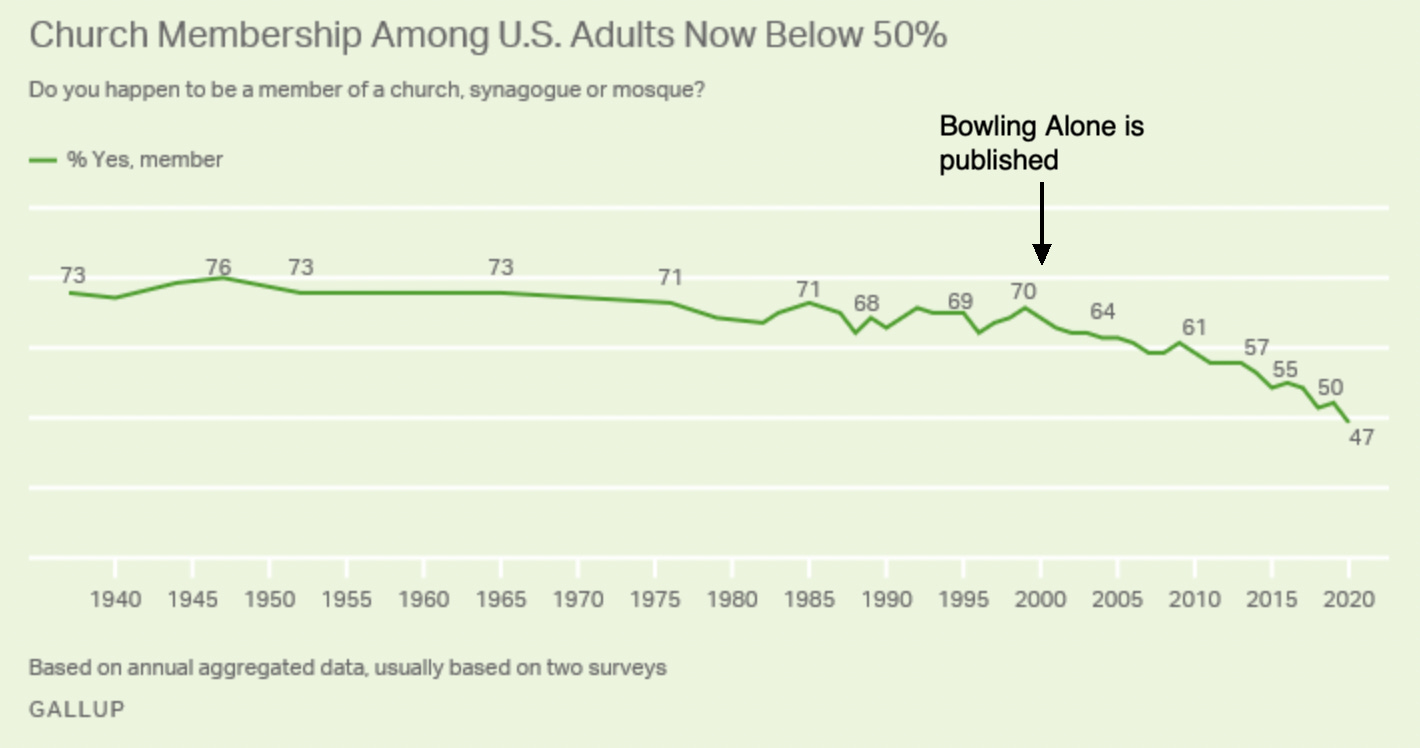

Anton Cebalo documents a decline in sex, friends and trust. Here’s a few points I found of interest. I had come to think about church membership in America as pretty much fixed around 70%. That was true for decades but not recently:

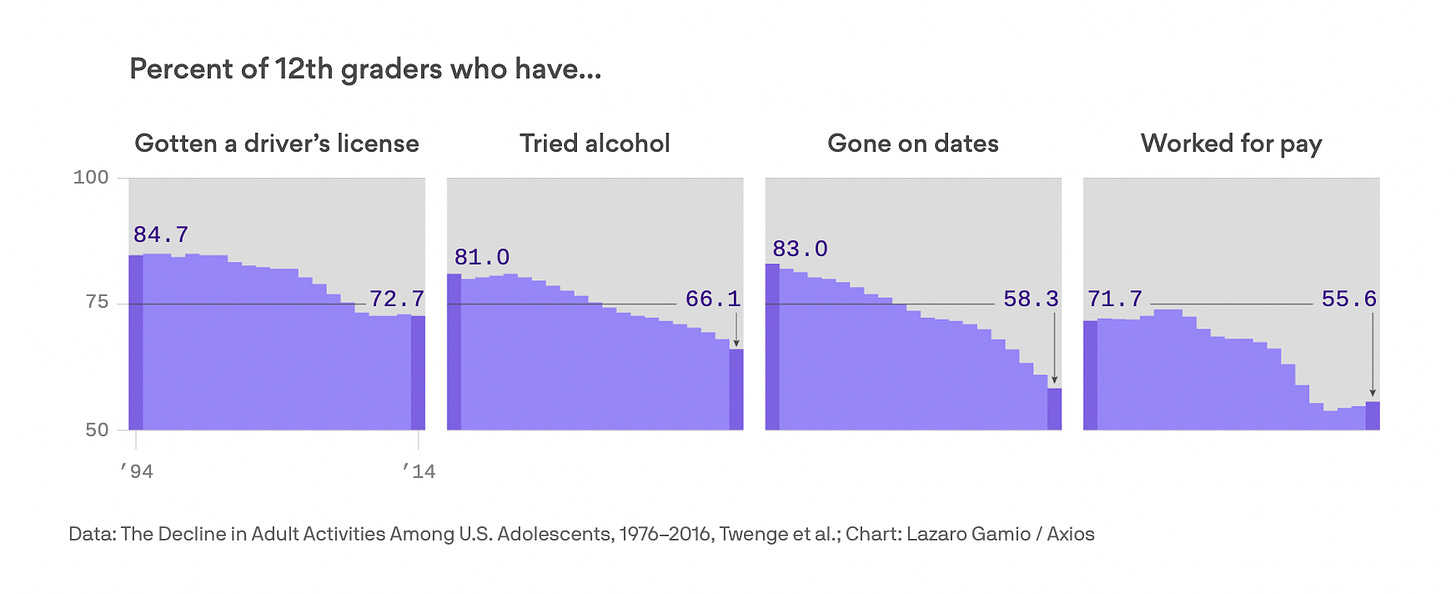

Here’s another trend, the extension of adoloscence. More and more we are treating young adults like children and in many respects they are more like children of earlier years.

There have been many psychological profiles of “late adulthood,” common among those born from the 1990s onward. Many of the milestones — getting a driver’s license, moving out, dating, starting work, and so on — have been delayed for many young adults.

The trend became obvious starting in the 2010s. In 2019, it was compiled in a comprehensive study titled The Decline in Adult Activities Among U.S. Adolescents, 1976-2016.

See Cebalo for more.

Are scientific breakthroughs less fundamental?

From Max Kozlov, do note the data do not cover the very latest events:

The number of science and technology research papers published has skyrocketed over the past few decades — but the ‘disruptiveness’ of those papers has dropped, according to an analysis of how radically papers depart from the previous literature.

Data from millions of manuscripts show that, compared with the mid-twentieth century, research done in the 2000s was much more likely to incrementally push science forward than to veer off in a new direction and render previous work obsolete. Analysis of patents from 1976 to 2010 showed the same trend.

“The data suggest something is changing,” says Russell Funk, a sociologist at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis and a co-author of the analysis, which was published on 4 January in Nature. “You don’t have quite the same intensity of breakthrough discoveries you once had.”

The authors reasoned that if a study was highly disruptive, subsequent research would be less likely to cite the study’s references, and instead cite the study itself. Using the citation data from 45 million manuscripts and 3.9 million patents, the researchers calculated a measure of disruptiveness, called the ‘CD index’, in which values ranged from –1 for the least disruptive work to 1 for the most disruptive.

The average CD index declined by more than 90% between 1945 and 2010 for research manuscripts (see ‘Disruptive science dwindles’), and by more than 78% from 1980 to 2010 for patents. Disruptiveness declined in all of the analysed research fields and patent types, even when factoring in potential differences in factors such as citation practices…

The authors also analysed the most common verbs used in manuscripts and found that whereas research in the 1950s was more likely to use words evoking creation or discovery such as, ‘produce’ or ‘determine’, that done in the 2010s was more likely to refer to incremental progress, using terms such as ‘improve’ or ‘enhance’.

Here is the piece, and here is the original research by Michael Park Erin Leahey, and Russell J. funk.

What is going wrong with American higher education?

Yes, yes all the Woke and PC stuff, but let us also look into the matter more deeply, as in my latest Bloomberg column. There is a serious talent drain due to excess bureaucratization, among other issues:

Another problem is the ongoing mental health crisis among America’s youth. This is not the fault of universities, to be clear, but a lot of unhappy students make for a less enjoyable college experience. The warm glow that so many baby boomers associate with their college years may not be reproduced by the current generation. They might instead look back on a quite troubled time, and in turn have less school loyalty.

I have also observed (as have many of my colleagues) that students seem to have more absences, excuses and missed assignments. No matter what the causes of those developments, they make it harder to run an effective university.

In fact, many of the smartest young people I know are deciding against a career in academia, even if that was their initial intent. They see too much bureaucracy and not enough time for the academic work itself. Students in the biosciences, at least the ones I talk to, seem to be an exception, perhaps because the opportunities to change the world are so obvious.

In my own field, economics, the prospect of having to do a “pre-doc” and then six years for a Ph.D. is driving away creative talent. On the research side, there is an obsession with finding the correct empirical techniques for causal inference. Initially a merited and beneficial development, this approach is becoming an intellectual straitjacket. There are too many papers focusing on a suitably narrow topic to make the causal inference defensible, rather than trying to answer broader, more useful but also more difficult questions.

…As committee obligations, paperwork and referee reports accumulate, the idea that academia allows you to be in charge of your own time seems ever more distant. Bureaucratization is eating away at the free time of professors. Much of the glamour of the job is gone, and my fear is that the system increasingly attracts conformists.

And don’t forget this disaggregation:

There are also big differences within universities. I have been a professor for more than three decades and speak often at other campuses. My impression is that presidents, provosts and deans are relatively sane, if only because they face real trade-offs as they draw up budgets, raise money and make payroll. University staff or student groups, on the other hand, often have no sense of the underlying constraints, and so advocate for ideas and practices that lead to some ridiculous stories. The actual decision makers are frequently not strong enough to push back, so they accept the demands as a way to survive or even advance.

Recommended.