Results for “time management” 347 found

The addict speaks (Ec 10 is over)

Lately, I have been spending some of my time writing this blog, which

started as a by-product of teaching ec 10, the principles class at

Harvard. I am still trying to figure out if this is a good use of my

time or not. On the one hand, this feels like providing a public good.

(Perhaps at a low cost: some of the time I spend on it has come from

watching reruns of Law and Order.) On the other hand, at times writing

this blog feels like being hooked on crack.

The real question is whether the addict realized this before his readers realized it about him. By the way, here are the addict’s tips on time management. (I disagree on travel, which I consider to be the best way of learning things.) Here is the addict linking to advice on getting through graduate school.

Has the addict figured out the biggest benefit of blogging, or is he just being coy?

We welcome the addict to a more lasting presence in the blogosphere.

Addendum: He also points our attention to economics videos.

Simple advice for academic publishing

Last week I gave a talk on career and publishing advice to a cross-disciplinary audience of graduate students. Here were my major points:

1. You can improve your time management. Do you want to or not?

2. Get something done every day. Few academics fail from not getting enough done each day. Many fail from living many days with zero output.

3. Figure out what is your core required achievement at this point in time — writing, building a data set, whatever — and do it first thing in the day no matter what. I am not the kind of cultural relativist who thinks that many people work best late at night.

4. Buy a book of stamps and use it. You would be amazed how many people write pieces but never submit and thus never learn how to publish.

5. The returns to quality are higher than you think, and they are rising rapidly. Lower-tier journals and presses are becoming worth less and less. Often it is the author certifying the lower-tier journal, rather than vice versa.

6. If you get careless, sloppy, or downright outrageous referee reports, it is probably your fault. You didn’t give the editor or referees enough incentive to care about your piece. So respond to such reports constructively with a plan for self-improvement, don’t blame the messenger, even when the messenger stinks. Your piece probably stinks too.

7. Start now. Recall the tombstone epitaph "It is later than you think." Darth Sidious got this one right.

8. Care about what you are doing. This is ultimately your best ally.

Here is a good article on academic book publishing and how it is changing.

Starting out as a Professor

Alex and Tyler like to post advice to graduate students (click here), which is usually on the mark. Here are some reflections from someone who has just finished the first year as a professor. I hope non-academic readers will enjoy knowing what this job is about.

1. Being a professor is all about time management. It’s important to spend time preparing classes and completing research but you have to be efficient. Unlike graduate school, you can’t spend years on a single dissertation chapter. It has to go to review soon, so you had better learn to write well and quickly.

2. This is really a cool job, but it is not for everybody. Although I am at a research university, I am expected to teach a fair amount – large undergraduate classes and doctoral students – and I must do a fair amount of administrative work. Anybody who is allergic to either activity should seek other employment. But if you like teaching, and you can thrive when you are expected to produce a lot in an unstructured environment, then it can be very satisfying.

3. Success in the academy is about writing skill – even in technical areas. Tyler might be interested in knowing that I learned this from him. Having brilliant ideas and doing the research to prove you are right is only half the battle. You must work very, very hard to clearly express your ideas and persuade skeptical readers.

While I consider myself to be a happy person, I still advise people not to go into academia – it is very competitive, smart people can make much more money elsewhere, there is little security pre-tenure and you can enjoy great ideas without getting a Ph.D. by reading Marginal Revolution every day.

Calendar facts

1. The U.S. calendar industry accounts for $1.2 billion a year.

2. The average American buys 2.5 calendars.

3. Dog calendars are especially popular. Bush and Britney Spears calendars have not been selling well.

4. The 2004 Nuns Having Fun calendar is now sold out.

5. Women prefer larger calendars than do men.

6. 70 percent of all calendar business is done in December, talk about seasonal business cycles.

7. Many calendar prices are cut in half on December 26.

8. Many calendars cost no more than a dollar by the end of January.

9. Less than one-third of Americans plan their workday in writing. One CEO of a time management firm reports: “Most people walk into work and don’t have a plan.”

From USA Today. If you are wondering, I bought my 2004 calendar in October and it portrays Hokusai prints.

Samuelson-Stolper, writ anew

At Sansan Chicken in Long Island City, Queens, the cashier beamed a wide smile and recommended the fried chicken sandwich.

Or maybe she suggested the tonkatsu — it was hard to tell, because the internet connection from her home in the Philippines was spotty.

Romy, who declined to give her last name, is one of 12 virtual assistants greeting customers at a handful of restaurants in New York City, from halfway across the world.

The virtual hosts could be the vanguard of a rapidly changing restaurant industry, as small-business owners seek relief from rising commercial rents and high inflation. Others see a model ripe for abuse: The remote workers are paid $3 an hour, according to their management company, while the minimum wage in the city is $16.

Here is more from the NYT, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

My excellent Conversation with Marc Rowan

Here is the video, audio, and transcript, taped in his Apollo office in NYC. Here is the episode summary:

Marc Rowan, co-founder and CEO of Apollo Global Management, joined Tyler to discuss why rising interest rates won’t hurt Apollo’s profitability, why liabilities have traditionally been the weak spot in insurance, why the concept of liquidity needs a rethink, the meaninglessness of the term “private credit”, what role crypto will play in American finance, why Marc bought a brutalist apartment, which country has beautiful new neighborhoods, what motivated Apollo’s office redesign, what he looks for in young hires, the different kind of decision-making required in debt versus private equity, the biggest obstacle to doing business in India, how university governance can be improved, what he’s learned from running restaurants, the next thing he’ll learn, and more.

And an excerpt:

COWEN: Now, how stable is all this as a political equilibrium? If you think about the four major banks, as you well know, there are very serious stress tests applied to them, capital requirements. The Fed is a major regulator. At least for insurance, it tends to be at the state level. One can reinsure through Bermuda. Capital requirements are very different. Competence of the state regulators arguably is lower than that of the Fed. Whether or not one wants more regulation — and generally, I don’t — but is this a stable situation? How’s it going to evolve?

ROWAN: First, I would have to correct almost everything you’ve said along the way to set the table for what I’m going to talk about. First, the difference between not so much the banking system and insurance, but the banking system and the investment marketplace. Let’s start with this — there are plenty of ways for investors to lose money. Investors can buy speculative stocks. They could buy the S&P. They can speculate in almost anything.

The making or losing of money is not, in and of itself, a systemically risky activity because, for good reason, we allow speculative investing every single day. Things go up, things go down. You can lose money in credit as well as in equity.

Now we come to mutual funds. If a mutual fund, which is daily liquid, owns credit, and investors want to get their money back, you’re right, price just adjusts. Mutual funds are not price guarantors. Are they regulated? Mutual funds are regulated. Are they disclosed and transparent? Yes, they’re disclosed and transparent. The holdings of a mutual fund are completely visible and they’re de-levered. Is that a risky activity because it moved out of the banking system and into a mutual fund? I don’t think so; I actually think it has de-risked. It’s made our economy and our financial system more resilient.

Now I’ll come to your question on political equilibrium. Insurance — if you just focus on insurance — has no federal guarantee, does not borrow short and lend long, has no access to the Fed, and does not do liquidity transformation or maturity mismatch, and they are forced to hold amounts of capital.

If you look — and I’ll give you a comparison just for us, not for the whole industry — who holds more capital, Athene our insurer as a percentage of assets or the typical bank? You would think the typical bank, but you would be wrong. We hold more capital per dollar of assets than anyone else. Who holds more investment-grade assets? Ninety percent of our book is investment-grade, the typical bank is two-thirds investment-grade.

COWEN: Sure, but that’s all time-sliced—

ROWAN: Let’s keep going.

COWEN: Money market funds have been a source of systemic risk, AIG has been —

ROWAN: I can’t tell you there’s not risks in the economy. We have a choice. We can have risk dispersed among lots of institutions, or we can have it concentrated in the government-backed, borrow-short, lend-long, government-guaranteed banking system.

Every time we disperse that risk, we make the system more resilient. If you want to focus on insurance, which is your question on political equilibrium, there’s more capital, there’s no ALM mismatch, there’s more investment-grade, and there is appropriate state-based regulation for institutions that do not have government guarantees or borrow from the Fed or do anything else.

Insurance is very slow-moving. We’re talking about, on average, 10-year assets. This is a very slow-moving process. Again, most of the issues that have happened in the insurance industry have not been asset issues. They’ve been liability issues, exactly the kind of thing that insurance-specialist regulation is designed to detect.

Recommended, and of course we talk about Marc’s higher ed campaign as well.

My Conversation with the excellent Ami Vitale

Here is the audio, visual, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

Ami Vitale is a renowned National Geographic photographer and documentarian with a deep commitment to wildlife conservation and environmental education. Her work, spanning over a hundred countries, includes spending a decade as a conflict photographer in places like Kosovo, Gaza, and Kashmir.

She joined Tyler to discuss why we should stay scary to pandas, whether we should bring back extinct species, the success of Kenyan wildlife management, the mental cost of a decade photographing war, what she thinks of the transition from film to digital, the ethical issues raised by Afghan Girl, the future of National Geographic, the heuristic guiding of where she’ll travel next, what she looks for in a young photographer, her next project, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: As you probably know, there’s a long-standing and recurring set of debates between animal welfare advocates and environmentalists. The animal welfare advocates typically have less sympathy for the predators because they, in turn, kill other animals. The environmentalists are more likely to think we should, in some way, leave nature alone as much as possible. Where do you stand on that debate?

VITALE: It depends. It’s hard to make a general sweeping statement on this because in some cases, I think that we do have to get involved. Also, the fact is, it’s humans in most cases who have really impacted the environment, and we do need to get engaged and work to restore that balance. I really fall on both sides of this. I will say, I do think that is, in some cases, what differentiates us because, as human beings, we have to kill to survive. Maybe that is where this — I feel like every story I work on has a different answer. Really, I don’t know. It depends what the situation is. Should we bring animals back to landscapes where they have not existed for millions of years? I fall in the line of no. Maybe I’m taking this in a totally different direction, but it’s really complicated, and there’s not one easy answer.

And:

COWEN: As you know, there are now social networks everywhere, for quite a while. Images everywhere, even before Midjourney. There are so many images that people are looking at. How does that change how you compose or think about photos?

VITALE: Well, it doesn’t at all. My job is to tell stories with images, and not just with images. My job as a storyteller — that has not changed. Nothing has changed in the sense of, we need more great storytellers, visual storytellers. With all of those social media, I think people are bored with just beautiful images. Or sometimes it feels like advertising, and it doesn’t captivate me.

I look for a story and image, and I am just going to continue doing what I do because I think people are hungry for it. They want to know who is really going deep on stories and who they can trust. I think that that has never gone away, and it will never go away.

I am very happy to have guests who do things that not everyone else’s guests do.

Sure on non-profit university board motives (from the comments)

Freedom of speech for university staff?

Put aside the more virtuous public universities, where such matters are governed by law. What policies should private universities have toward freedom of speech for university staff? This is not such a simple question, even if you are in non-legal realms a big believer in de facto freedom of speech practices.

Just look at companies or for that matter (non-university) non-profits. How many of them allow staff to say whatever they want, without fear of firing? What if a middle manager at General Foods went around making offensive (or perceived to be offensive) remarks about other staff members? Repeatedly, and after having been told to stop. There is a good chance that person will end up fired, even if senior management is not seeking to restrict speech or opinion per se. Other people on the staff will object, and of course some of the offensive remarks might be about them. The speech offender just won’t be able to work with a lot of the company any more. Maybe that person won’t end up fired, but would any companies restrict their policies, ex ante, to promise that person won’t be fired? Or in any way penalized, set aside, restricted from working with others or from receiving supervisory promotions, and so on?

You already know the answers to those questions.

Freedom of speech for university staff is a harder question than for students or faculty. Students will move on, and a lot of faculty hate each other anyway, and don’t have to work together very much. Plus the protection of tenure was (supposedly?) designed to support freedom of speech and opinion, even “perceived to be offensive” opinions. As for students, we want them to be experimenting with different opinions in their youth, even if some of those opinions are bad or stupid. Staff in these regards are different.

Staff are growing in numbers and import at universities. They often are the leaders of Woke movements. Counselors, Director of Student Affairs, associate Deans, and much more. Then there are the events teams and the athletic departments, and more yet. Perhaps some schools spend more on staff than on faculty?

While it is hard to give staff absolute free speech rights, it is also hard to give them differential free speech rights. A cultural tone is set within the organization. If everyone else has free speech rights, how exactly do you enforce restrictions on staff? Should a university set up a “thought police” but for staff only? Can you really circumscribe the powers of such a thought police over time? Besides, what if a staff member signs up for a single night course? Do they all of a sudden have the free speech rights of students? How might you know when they are “speaking as a student” or “speaking as a staff member”? Or what if staff are overseeing the free speech rights of faculty and students, as is pretty much always the case? The enforcers of student free speech rights don’t have those same free speech rights themselves? What kind of culture are they then being led to respect and maintain? And what if staff are merely expressing their opinions off-campus, say on their Facebook pages? Does all that get monitored? Or do you simply encourage one set of people to selectively complain about another set, as a kind of weaponization of some views but not others?

You might have your own theoretical answers to these conundrums, but the cultural norms of large institutions usually aren’t finely grained enough to support them all.

If you think that free speech rights for university staff are an easy question, I submit you haven’t thought about this one long and hard enough.

Work From Home Works

It took firms decades to adjust to electricity by redesigning factories, products, and workflows to take full advantage of the new possibilities. Similarly, the benefits of work from home start to come most profoundly when expensive offices can be shrunk, employers can draw from a much larger pool of workers and workers can adjust when and where they work, including the location of their homes. It’s not surprising, therefore, that with little time for either the workers or the firms to adjust and with few options to choose how much to work from home, productivity fell when COVID sent workers home. But, with more time to plan and more options for hybrid but extensive work from home (e.g. work from home Mondays and Fridays), work from home has large benefits. We are also seeing management redesign to take advantage of work from home in the same way we saw factory redesign to take advantage of electricity. Management, for example, is shifting from input metrics–do you show up?–to output metrics–did the work get done? Designing and validating new metrics takes time, but these changes are helping to increase the benefits of work from home.

Nick Bloom reviews the evidence (slides here).

Looking at micro economic studies on working from home productivity, the classic is “The Stanford Study” I helped oversee in 2010-2012. We randomized 250 employees in a large multinational firm into those who would work from home and those who would report to the office. The expectation, of course, was that home-based employees would goof-off, sleeping or watching TV rather than working.

So, we were shocked to find a massive 13 percent increase in productivity.

The productivity boost came from two sources. First, remote employees worked 9 percent more in minutes per day. They were rarely late to work, spent less time gossiping and chatting with colleagues, and took shorter lunch breaks and fewer sick days. Remote employees also had 4 percent more output per minute. They told us it’s quieter at home. The office was so noisy many of them struggled to concentrate.

The macro evidence also suggests or at least is consistent with work from home working:

In the five years before the pandemic, U.S. labor productivity growth was 1.2 percent; since 2020, this picked up to 1.5 percent. Given the state of the world, that acceleration was miraculous.

What could have caused this? Perhaps rising government expenditure and easy monetary policy? Possibly, but greater government activity traditionally is associated with lower, not higher, productivity growth. Perhaps an acceleration in technology and computerization? Possibly, but the pandemic did not witness any pickup in technological progress. Perhaps the five-fold surge in working from home post-pandemic. Maybe cutting billions of commuting hours, replacing millions of business trips with Zoom meetings, increasing the labor supply of Americans with disabilities or child-care commitments, and saving millions of square feet of office space increased productivity? It is honestly hard to say.

Revealed preference is the most telling piece of evidence. Workers value the option to work from home and many firms now advertise the options for hybrid work as a benefit:

…millions of firms around the world are adopting hybrid and remote work, there has to be something there. I have spoken to many hundreds of managers and firms over the last three years and I repeatedly hear they use home working as a key part of their recruitment and retention strategy. Indeed, another recent experiment on 1600 employees found hybrid reduced employee quit rates by 35 percent. \

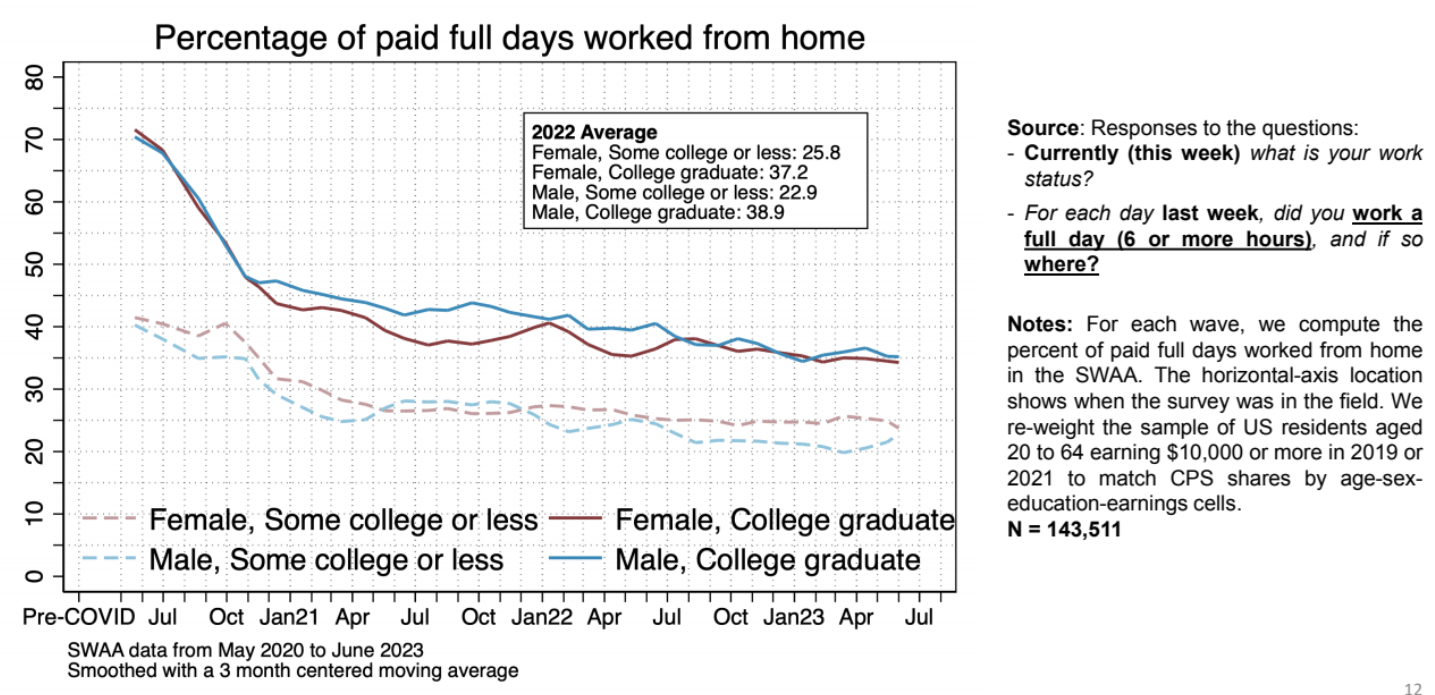

Despite a rocky start, work from home appears to have stabilized at around 25% of work days overall and stunningly, nearly 40% of work days for college educated workers! Work from home thus appears to be a permanent and beneficial change in how work is structured.

Why are Gender Pay Gaps so Large in Japan and South Korea?

From Alice Evans:

Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan are closing gender gaps in pay, seniority and parliamentary representation. Japan and South Korea, meanwhile, have the largest gender pay gaps in the OECD. Management remains 85% male. Female graduates are treated like secretaries, expected to pour the tea and run errands.

In Japan, a female graduate earns the same as a man who has only completed school. For Korean women aged 25-39, gender gaps in wages are indistinguishable between those with children and those without. In Europe, by contrast, there is a major penalty for motherhood.

Japanese businesses have lobbied again legislative change, even refusing sexual harassment training. Courts routinely deny systematic discrimination. Employers cannot even be sued for sexual harassment. Employees can only ask the Ministry of Labour for mediation. Accusations of abuse are mostly ignored.

At least part of the explanation stems from the lifetime full employment norms of Japan and South Korea, not present in Taiwan or Singapore, where those wage gaps are lower.

To summarise, Japan and South Korea have enshrined a system of lifetime employment and seniority pay for both blue collar and white collar workers. Firms are extremely sexist: men are treated as future managers, women are their subordinates. These inequalities are largest amongst low status regular workers. Fed up and frustrated, wives quit regular work to spend more time with their children and undertake non-regular, low paid work.

That is only part of the argument, here is the entire piece.

The economics of NBA contracts

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

The Boston Celtics just set an NBA record by agreeing to a five-year, $304 million contract with two-time All-Star Jaylen Brown. The obvious question is whether any single basketball player can be worth that much money — especially someone who is not even the best player on his team, much less on a par with Lebron James, Stephen Curry or any number of other shoo-in hall of famers.

I’m not here to make predictions about Brown’s career. But the odds are the deal will be seen as a good one — maybe even a bargain. The economics of the National Basketball Association have been shifting toward more and more money.

This trend is evident in the rising value not just of players but of teams. Last year the Phoenix Suns sold for $4 billion (with the WNBA’s Phoenix Mercury). To put that number in perspective, the Brooklyn Nets sold for $3.3 billion in 2019, the Houston Rockets sold for $2.2 billion in 2017, and the Atlanta Hawks sold for a mere $850 million in 2015.

Much of the rest of the column considers the impact of foreign money on other sports, and perhaps someday the NBA:

And then there is the growing internationalization of capital in sports, which will buttress high prices for both players and teams. This trend goes beyond American basketball: One Saudi Arabian club, Al-Hilal, has offered French soccer star Kylian Mbapp é $333 million to play next year in Saudi Arabia. The Saudis are already paying Cristiano Ronaldo $220 million over two years. Lionel Messi turned the Saudis down, but surely the offer increased his bargaining power with MSL’s Inter Miami, where his deal is valued at $50 to $60 million annually.

Might the Saudis consider something similar for a US basketball star? Lebron James already tweeted that he would gladly accept a comparable offer, and many others would accept far less.

The Desert Kingdom would probably have a hard time putting together a full NBA-like season with 30 teams. But it could bring in more European or other foreign players to its current league, shorten the season, or feature 3-on-3 games. In addition to wealth, they need to rely on innovation.

These scenarios don’t have to happen to serve as a check on NBA management or owners.

Qatar owns five percent of the Washington Wizards, we will see if this becomes a larger basketball trend or not.

David J. Deming now has a Substack

Forked Lightning, he is from the Harvard Kennedy School, and he is a co-author on the piece with Chetty and John N. Friedman featured on MR earlier today.

In his inaugural post he explains some further results from the paper in more detail:

The second part [of the paper] shows the impact of attending an Ivy-Plus college. Do these colleges actually improve student outcomes, or are they merely cream-skimming by admitting applicants who would succeed no matter where they went to college?[2]

We focus on students who are placed on the waitlist. These students are less qualified than regular admits but more qualified than regular rejects. Crucially, the waitlist admits don’t look any different in terms of admissibility than the waitlist rejects. We verify this by showing that being admitted off the waitlist at one college doesn’t predict admission at other colleges. Intuitively, getting in off the waitlist is about class-balancing and yield management, not overall merit. The college needs an oboe player, or more students from the Mountain West, or whatever. It’s not strictly random, but it’s unrelated to future outcomes (there are a lot of technical details here that I’m skipping over, including more tests of balance in the waitlist sample – see the paper for details). We also show that we get similar results with a totally different research design that others have used in past work (see footnote 2).

Almost everyone who gets admitted off an Ivy-Plus college waitlist accepts the offer. Those who are eventually rejected go to a variety of other colleges, including other Ivy-Plus institutions. We scale our estimates to the plausible alternative of attending a state flagship public institution. In other words, we want to know how an applicant’s life outcomes would differ if they attended a place like Harvard (where I work) versus Ohio State (the college I attended – I did not apply to Harvard, but if I did I surely would have been *regular* rejected!)

We find that students admitted off the waitlist are about 60 percent more likely to have earnings in the top 1 percent of their age by age 33. They are nearly twice as likely to attend a top 10 graduate school, and they are about 3 times as likely to work in a prestigious firm such as a top research hospital, a world class university, or a highly ranked finance, law or consulting firm. Interestingly, we find only small impacts on mean earnings. This is because students attending good public universities typically do very well. They earn 80th-90th percentile incomes and attend very good but not top graduate schools.

The bottom line is that going to an Ivy-Plus college really matters, especially for high-status positions in society.

In a further Substack post, Deming explains in more detail why the classic Dale and Kruger result (that, adjusting for student quality, you can go to the lesser school) no longer holds, due to limitations in their data. Of course all this bears on the “education as signaling” debates as well.

By the way, it took the authors more than five years to write that paper. Deming adds: “The paper is 125 pages long. It has 25 main exhibits (6 tables and 19 figures), and another 36 appendix exhibits.”

Here is Deming’s home page. He is a highly rated economist, yet still underrated.

Neanderthal bone markets in everything?

Did Neanderthal produce a bone industry? The recent discovery of a large bone tool assemblage at the Neanderthal site of Chagyrskaya (Altai, Siberia, Russia) and the increasing discoveries of isolated finds of bone tools in various Mousterian sites across Eurasia stimulate the debate. Assuming that the isolate finds may be the tip of the iceberg and that the Siberian occurrence did not result from a local adaptation of easternmost Neanderthals, we looked for evidence of a similar industry in the Western side of their spread area. We assessed the bone tool potential of the Quina bone-bed level currently under excavation at chez Pinaud site (Jonzac, Charente-Maritime, France) and found as many bone tools as flint ones: not only the well-known retouchers but also beveled tools, retouched artifacts and a smooth-ended rib. Their diversity opens a window on a range of activities not expected in a butchering site and not documented by the flint tools, all involved in the carcass processing. The re-use of 20% of the bone blanks, which are mainly from large ungulates among faunal remains largely dominated by reindeer, raises the question of blank procurement and management. From the Altai to the Atlantic shore, through a multitude of sites where only a few objects have been reported so far, evidence of a Neanderthal bone industry is emerging which provides new insights on Middle Paleolithic subsistence strategies.

That is from a new paper by Malvina Baumann, et.al. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Private ownership sentences to ponder

Anyone keen to understand how should look at Brookfield Renewable Partners’ recent investment of up to $2 billion in Scout Clean Energy and Standard Solar. B.R.P. is a vehicle of Brookfield Asset Management, a leading global asset management firm, with around $800 billion of assets under management, and it purchased two American developers and owner-operators of wind and solar power-generating facilities. This took place six weeks after President Biden signed the I.R.A. into law.

The I.R.A. will help accelerate the growing private ownership of U.S. infrastructure and, in particular, its concentration among a handful of global asset managers like Brookfield. This is taking the United States into risky territory. The consequences for the public at large, whose well-being depends on the quality and cost of a host of infrastructure-based services, from energy to transportation, are unlikely to be positive.

A common belief about both the I.R.A. and 2021’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, President Biden’s other key legislation for infrastructure investment, is that they represent a renewal of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal infrastructure programs of the 1930s. This is wrong. The signature feature of the New Deal was public ownership: Even as private firms carried out many of the tens of thousands of construction projects, almost all of the new infrastructure was funded and owned publicly. These were public works. Public ownership of major infrastructure has been an American mainstay ever since…

So it would be truer to say that in political-economic terms, Mr. Biden, far from assuming Roosevelt’s mantle, has actually been dismantling the Rooseveltian legacy. The upshot will be a wholesale transformation of the national landscape of infrastructure ownership and associated service delivery.

That is from Brett Christophers (NYT), who is disapproving. For an alternative view, see this WSJ Op-Ed by Katherine Boyle and David Ulevitch.

Here is the link, though not on the whole worth threading through.