What happens when dating goes online?

This paper studies how online dating platforms have impacted marital outcomes, assortative matching, and sexually transmitted disease (STD) rates in the United States. We construct county-level measures of online dating usage using data from website-based platforms (2002-2013) and mobile app-based platforms (2017-2023). Leveraging county-level variation and an instrumental variable strategy, we show in the desktop era, a 1% increase in online dating sessions raises divorce rates by 0.50%, while in the mobile era, a 1% increase in online dating activity lowers marriage and divorce rates by 0.40% and 0.33%, respectively. We also document shifts in assortative matching. Desktop sites reduce sorting along education and employment dimensions, whereas mobile sites reduce sorting by employment, but increase sorting by race. Across both eras, we find no evidence that greater online dating usage increases average STD rates. Average effects are negative or statistically insignificant, but are positive for some subpopulations. We develop a search and matching model where technological changes impact search costs, market size, and market noise can explain our empirical findings.

That is from a new paper by Daniel Ershov, Jessica Fong, and Pinar Yildirim. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Tuesday assorted links

1. European T-Bill sales are not an effective threat.

2. Is the 1963 The Essex hit song “Easier Said than Done” actually about a white woman who cannot bring herself to confess her love for a black man?

3. New Zealand is contracting (NYT). And Knausgaard overview (NYT).

6. In America, would fewer bus stops be better?

8. China fact of the day: “Put differently, there were fewer births in China in 2025 than in 1776”

9. Does the Japanese bond shock mean tighter global liquidity?

The Most Significant Discovery in the History of Biblical Studies

The great biblical scholar, Bart Ehrman, gave his retirement lecture at UNC. It’s an excellent overview on the theme of the most significant discovery in the history of biblical studies. After encomiums, Bart starts around the 13:30 mark with about 10 minutes of amusing biography. He gets into the meat of the lecture at 24:38 which is where it is cued.

Keeping matters in perspective

Moreover, China’s expanding leadership in scientific production has not translated into a commensurate shift in global diffusion and integration. Elite research remains disproportionately focused on US topics (40% of breakthrough publications), and citations to Chinese research disproportionately come from within China rather than from other regions, even for top-tier science.

That is from a new NBER working paper on the geography of science, by

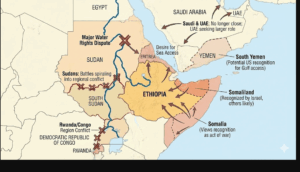

Fear of larger wars in East Africa

This is one of my major worries for 2026 and beyond. The ethnic and tribal conflict in Ethiopia is not finished, and it killed 700,000 people not long ago. Ethiopia still covets sea access and Eritrea, which at times in the past belong to Ethiopia anyway. Israel has recognized Somaliland, with a variety of other countries, including the United States, likely to follow. For Somalia, that is akin to an act of war because it dismembers what they perceive as their country. Somalia and Ethiopia still have troubles. Ethiopia and Egypt have a major dispute over water rights, a possible casus belli.

The United States, and thus other countries too, might recognize South Yemen, in an attempt to better control Gulf access. This is not nominally Africa but it is a very real African issue as well.

Saudi and UAE are no longer close in a manner that enable them to collectively bring order to the area. More generally, political property rights are weak in the region, many borders are contested, and there is no generally acknowledged legitimate referee. UAE is seeking to play a larger role, perhaps with a good deal of hubris. Trump is Trump.

The battles in the Sudans may be spiraling into a larger regional conflict. There is also Rwanda and the Congo region.

So I am worried.

Is there a British productivity comeback?

Let us hope:

Britain is seeing early signs of a long-awaited turnaround of its productivity woes, according to an alternative measure that suggests output per hour worked has risen at a pace not seen since before the financial crisis.

The Resolution Foundation said a “blistering” productivity surge has been masked by problems with official statistics and pointed to encouraging indications of a clearout of “zombie” firms that contribute little to the economy.

Productivity growth, when measured using the Office for National Statistics’ troubled Labour Force Survey, was just 1.1% in the year through the third quarter of 2025. But the figures look far better when based on employee payrolls data that are more trusted by economists, the think tank said.

“Productivity was essentially flat between the pre-pandemic peak of Q4 2019 and post-pandemic trough of Q1 2024, but it has grown by a blistering 3.4% in the six quarters after that, a rate not seen since before the financial crisis,” the Resolution Foundation said in a report published Monday. Those gains are more than the previous seven years combined, it added.

Here is more from Bloomberg. I will update you on this as I learn more.

Monday assorted links

1. Republican investigators are not finding much electoral fraud (NYT).

2. New Yorker interview with Amanda Seyfrieds (of Ann Lee fame). An interesting movie, by the way. 28 Years Later is also very good, though too gory for most people, myself included. Watch it if you can.

4. Why it is hard to run Venezuela (NYT).

6. Hunter Thompson, belated and stochastic RIP (NYT).

7. Ralph Towner, RIP (NYT).

Greenland fact of the day

Greenland held a referendum on 23 February 1982 and voted to leave the European Communities / European Economic Community (EEC) (about 52–53% for leaving).

GPT link. They left in 1985.

I write this not to justify current American policy, which I consider a major mistake with extremely poor execution. Rather the point is that we are pushing the Greenlanders into the arms of the Danes, when over some longer haul it could be very different.

The FT offers many more interesting facts about Greenland, including its growing dependence on Asian foreign labor.

Morally judging famous and semi-famous people

This is one of the worst things you can do for your own intellect, whatever you think the social benefits may be. I know some reasonable number of famous people, and I just do not trust the media accounts of their failings and flaws. I trust even less the barbs I read on the internet. I am not claiming to know the truth about them (most of them, at least), but I can tell when the people writing about them know even less.

I am not saying everyone is an angel — sometimes you come to learn negative information that in fact is not part of the standard press reports or internet whines.

If you are going to possibly be working with someone on a concrete and important project, absolutely you should be trying to form an assessment of their moral quality and reliability. (And you are allowed to do it once per electoral race, when deciding for whom to vote.) But if not, spending real time and energy morally judging famous and semi-famous people is one of the best and quickest ways to make yourself stupider. Focus on the substantive arguments for and against various policies and propositions, not the people involved. Furthermore, smart people do not seem to be immune from this form of mental deterioration. Here is my 2008 post on “pressing the button.”

A corollary of this is that if you read an internet comment that, when a substantive issue is raised, switches to judging a famous or semi-famous person, the quality of that comment is almost always low. Once you start seeing this, you cannot stop seeing it.

Addendum: If by any chance you are wondering how to make yourself smarter, learn how to appreciate almost everybody, and keep on cultivating that skill.

Podcast with Salvador Duarte

Salvador is 17, and is an EV winner from Portugal. Here is the transcript. Here is the list of discussed topics:

0:00 – We’re discovering talent quicker than ever 5:14 – Being in San Francisco is more important than ever 8:01 – There is such a thing like a winning organization 11:43 – Talent and conformity on startup and big businesses 19:17 – Giving money to poor people vs talented people 22:18 – EA is fragmenting 25:44 – Longtermism and existential risks 33:24 – Religious conformity is weaker than secular conformity 36:38 – GMU Econ professors religious beliefs 39:34 – The west would be better off with more religion 43:05 – What makes you a philosopher 45:25 – CEOs are becoming more generalists 49:06 – Traveling and eating 53:25 – Technology drives the growth of government? 56:08 – Blogging and writing 58:18 – Takes on @Aella_Girl, @slatestarcodex, @Noahpinion, @mattyglesias, , @tszzl, @razibkhan, @RichardHanania, @SamoBurja, @TheZvi and more 1:02:51 – The future of Portugal 1:06:27 – New aesthetics program with @patrickc.

Self-recommending, here is Salvador’s podcast and Substack more generally.

Those new (old) service sector jobs, chimney sweep edition

Now, many sweeps, including those in the Firkins family business, say the trade has been experiencing an improbable resurgence.

According to the National Association of Chimney Sweeps, demand has been bolstered by high energy prices, the popularity of wood-burning stoves and an international climate that has prompted warnings that electricity supplies could be vulnerable to attack by hostile states like Russia.

“People are thinking, ‘Let’s have a backup, let’s have a fire, let’s have a stove in case the electricity goes off,’” said Martin Glynn, the president of the chimney sweeps association, whose membership has risen to about 750 today, from about 590 in 2021. “If you have the ability to burn logs or smokeless fuel, you can keep cooking and have some heating. There is a big increase in demand and people are reopening their fireplaces.”

On a recent day, he said, three people had booked training courses. The association’s membership now includes 40 female sweeps. “It’s alive and kicking,” he said of the group, adding: “We don’t send little boys up chimneys any more, instead it’s CCTV and smoke testing equipment. It’s almost like being a chimney technician.”

Here is more from the NYT, via Mike Rosenwald.

Tim Kane on my visit to University of Austin

Here is the link, I should add that in addition to my enthusiasm for the students, the faculty also seemed quite good, most of all knowledgeable and open. I know very little about how the school is run, you might try this short piece from Arnold Kling, who has been visiting there for a week.

Here is an excerpt from Tim:

Tyler made a remark that he didn’t think fighting grade inflation matters very much. I respect his opinion, but I think he’s wrong. And I hope I can change his mind. Here’s why I care so much about it, and why I think a GPA target is the only — literally the only — effective solution. A college cannot fight grade inflation with rhetoric and goals and hand-wringing. Genuine academic rigor requires strong limits on what faculty can do with grades.

Professors everywhere have a large incentive to give higher grades. The situation has inflated asymptotically to the ceiling for 8 decades, particularly at the Ivies…

At University of Austin, all professors have to give an average grade of B. Here is more from Tim:

Consequences?

- More learning. UATX students are focused on learning, not grades.

- Less squabbling. Faculty are seeing way fewer ticky-tack arguments over a single point on homework and exams because the students aren’t obsessed with the 4.0 or 3.0 threshholds.

- More studying, especially increased follow-through. The incentives for students to care about final exams are stronger (none of this late-term “that grade is already settled, so I am blowing off that final exam” nonsense.)

- Less anxiety. I skimmed the grades data for our fall semester and am pretty sure I did not see a single “perfect” grade of 100/100 for any student in any class.

Some of you have asked me what I think of the recent Politico article on University of Austin. First, I have not been involved in any of the cited disputes, so I cannot speak to their details. Second, I do not not not speak for the University at all (while I am on the Advisory Board, it is an unpaid position with no authority or fiduciary responsibility and my advice/consultation has been on the AI topic). But I would make these more general points:

a. If a university decided to be based explicitly on classical liberal perspectives and principles, I would think that is great (not saying what is the best way to describe U. Austin, this is a general observation). I would however worry that the decision is not sustainable over time at much scale, given the career incentives of so many of the people who will be hired.

b. If that decision to be “classically liberal in orientation” required the administration to set some general principles to try to assure that the faculty at said school did not evolve into being like the faculty almost everywhere else, I would be fine with that.

c. I think such a school, over time, if it stuck to its principles, would end up with more de facto free speech than most other institutions of higher education.

d. I am glad that Notre Dame and Georgetown are Catholic schools, that UC Santa Cruz was founded as a kind of hippie school, that there is Yeshiva, the New School, HBCUs, and so on. I favor schools being “more different” ideologically in a variety of directions, including those I do not agree with, which of course will cover the majority of cases. My main objection is that many of the “Catholic” schools for instance are not very Catholic anymore, having been taken over by a kind of rampant general professionalism. I hope University of Austin avoids that fate. I should add that I am well aware that the general rise in fixed costs makes such endeavors much harder to sustain these days. I would like to reverse that general trend, and that is one reason for my interest in online and AI-oriented methods in education.

e. To innovate, more and more schools will have to move away from the old “faculty control” model. This change is already substantially underway, sans the innovation however.

f. Failure to contextualize is often the greatest “sin” of media articles offering coverage of disputes.

Returning to the University of Austin, right now their entering class is about 100 students, and they offer 35 classes a semester. It is one floor in an office building, and it is not costing any taxpayer dollars. It is a tiny, tiny drop in the bucket. GMU alone has about 40,000 students, and is basically a city. My Principles class this last fall alone had about 3.5x more students than are in the entire U. Austin.

If you are very upset by whatever is going on at U. Austin, or not going on, or whatever…I would say that is the real story.

When did Argentina lose its way?

From a new paper by Ariel Coremberg and Emilio Ocampo:

This paper challenges the increasingly popular view that Argentina’s economy performed relatively well under the corporatist import substitution industrialization (CISI) regime until the mid-1970s, and that its much-debated decline began only after 1975. Instead, it advances the alternative hypothesis that although real GDP per capita growth during this period was high by Argentina’s historical standards, it was low relative to the rest of the world, to typical comparator countries, and to what was achievable given the country’s factor endowments and investment levels. Distortions in relative prices and systemic capital misallocation generated significant inefficiencies that constrained economic dynamism and limited productivity gains. We support this hypothesis using a range of empirical methodologies—including comparative GDP per capita ratios, convergence analysis, growth accounting, and cyclical peak-to-peak analysis— complemented by historical interpretation. Although post-1955 modifications to the CISI regime temporarily improved performance, by the early 1970s it had exhausted its capacity to sustain growth. The prolonged stagnation that followed the 1975 crisis can be explained by the inability of successive governments to overcome the resistance of entrenched interest groups and thus complete the transition to an open market economy. Abrupt regime reversals fostered social conflict, political instability, and macroeconomic uncertainty, all of which undermined the sustained productivity gains required for long-term growth.

Via the excellent Samir Varma.

Childhood neighbors matter

We explore the role of immediate next door neighbors in affecting children’s later life occupation choice. Using linked historical census records for over 6 million boys and 4 million girls, we reconstruct neighborhood microgeography to estimate how growing up next door to someone in a particular occupation affects a child’s probability of working in that occupation as an adult, relative to other children who grew up farther away on the same street. Living next door to someone as a child increases the probability of having the same occupation as them 30 years later by about 10 percent. As an additional source of exogenous variation in exposure to next door neighbors, we exploit untimely neighbor deaths and find smaller and insignificant exposure effects for children who grew up next to a neighbor with an untimely death. We find larger exposure effects when intensity of exposure is expected to be higher, and document larger occupational transmission in more connected neighborhoods and when next door neighbors are the same race or ethnicity or have children of similar ages. Childhood exposure to next door neighbors has real economic consequences: children who grow up next to neighbors in high income or education occupations see significant gains in adult income and education, even relative to other children living on the same street, suggesting that neighborhood networks significantly contribute to economic mobility.

That is from a recent paper by Michael Andrews, Ryan Hill, Joseph Price, and Riley Wilson. Via Kris Gulati.

*Pee-wee as himself*

I loved this documentary, all three hours of it. Perhaps you need to be American, and to have lived in Pee-wee’s decades? In any case, the film is a wonderful reflection on self-knowledge, the changing status of “coming out” as gay in American history, celebrity, how fame happens, hippie culture, cancel culture, who your real friends are, narcissism, and much more. Pee-wee collaborated with the making of the film, but it seems pretty honest in portraying his life and later legal troubles. It turns out he was dying of cancer for years, but did not let on to the filmmakers. Here is the official trailer.