Pulse

Today we are launching my favorite feature of ChatGPT so far, called Pulse. It is initially available to Pro subscribers.

Pulse works for you overnight, and keeps thinking about your interests, your connected data, your recent chats, and more. Every morning, you get a custom-generated set of stuff you might be interested in. It performs super well if you tell ChatGPT more about what’s important to you.

In regular chat, you could mention “I’d like to go visit Bora Bora someday” or “My kid is 6 months old and I’m interested in developmental milestones” and in the future you might get useful updates.

Think of treating ChatGPT like a super-competent personal assistant: sometimes you ask for things you need in the moment, but if you share general preferences, it will do a good job for you proactively.

This also points to what I believe is the future of ChatGPT: a shift from being all reactive to being significantly proactive, and extremely personalized.

That is from Sam Altman.

Is a mild stagflation coming?

That is the topic of my latest article for The Free Press. The general picture is not altogether encouraging:

How about unemployment?

The labor market has been deteriorating, albeit slowly, since the waning days of the Biden administration. Indeed, for the first time since 2021, there are more unemployed Americans than there are open jobs.

Economists can only guess as to why this is happening. Some like to argue that labor markets are “taking a pause” or have “run out of steam,” two metaphors that may hold some truth but should not be mistaken for well-reasoned explanations. Another popular hypothesis is that artificial intelligence has slowed new hiring. That may be true for some sectors, such as mid-tier tech programmers or call center workers, but it is unlikely to have a large enough effect to account for most of the recent labor market slowdown.

As the Bureau of Labor Statistics has revised job creation numbers, it has become increasingly clear that the American economy has not been creating many new jobs for some time. For instance, revised numbers show that between April 2024 and March 2025, the economy generated 911,000 fewer jobs than the initial monthly calculations. Revisions to the June figures even showed a loss of 13,000 jobs. That is bad news in its own right, but it is also a negative harbinger for the future.

Once workers begin losing their jobs—and job creation weakens more generally—a kind of cumulative unraveling can take place. For instance, jobless workers have less money to spend, which decreases demand in the economy, and that usually translates into further job loss. Once the job loss dynamic is set in general motion, it can accelerate rapidly.

Uncertainty surrounding the Trump tariffs has also discouraged private sector investment, which weakens future job creation. So the best bet is that the economy, a year or two from now, will have noticeably higher unemployment.

Note that gdp growth might remain fine, so it will be a funny kind of stagflation…

Thursday assorted links

1. Energy projects delayed or cancelled.

2. Roger Scruton, predicting 1997 for Britain.

3. One definition of “the South.” This guy should get a job gerrymandering?

5. Takatoshi Ito, RIP. Japanese advocate of inflation targeting.

6. Per year.

Who are the important intellectuals today, under the age of 55?

I do not mean public intellectuals, though they are an important category of their own. For this question in earlier times you might have mentioned Foucault, Nozick, or Jon Elster. They were public intellectuals of a sort, but they also carried considerable academic heft in their own right. They promoted ideas original to them.

So who today are the equivalents? Important, original thinkers. With impact. You look forward to their next book or proclamation. Under age 55. Bitte.

Reading Orwell in Moscow

In this paper, I measure the effect of conflict on the demand for frames of reference, or heuristics that help individuals explain their social and political environment by means of analogy. To do so, I examine how Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 reshaped readership of history and social science books in Russia. Combining roughly 4,000 book abstracts retrieved from the online catalogue of Russia’s largest bookstore chain with data on monthly reading patterns of more than 100,000 users of the most popular Russian-language social reading platform, I find that the invasion prompted an abrupt and substantial increase in readership of books that engage with the experience of life under dictatorship and acquiescence to dictatorial crimes, with a predominant focus on Nazi Germany. I interpret my results as evidence that history books, by offering regime-critical frames of reference, may serve as an outlet for expressing dissent in a repressive authoritarian regime.

That is from a job market paper by Natalia Vasilenok, political science at Stanford. Via.

What of American culture from the 1940s and 1950s deserves to survive?

In the comments, Elijah asks:

Would love to read a post about which movies and novels from this era do and do not deserve to survive and why.

I do not love 20th century American fiction, so maybe I am the wrong person to ask. I started with GPT-5, which gave this list of novels from those two decades. I’ve read a significant percentage of those, and would prefer:

Raymond Chandler, J.D. Salinger, Nabokov, Patricia Highsmith, Shirley Jackson, and lots of science fiction. The I, Robot stories are from the 1940s, and the book published in 1950. A lot of the “more serious” entries on that list I feel have diminished somewhat with age.

Great Hollywood movies from that era are too numerous to name. In music there is plenty of jazz, plus Elvis, Chuck Berry, James Brown, Buddy Holly, doo wop, “the roots of rock” (includes some one hit wonders), Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, the Everlies, the Louvin Brothers, Johnny Cash, lots of country and bluegrass and blues, and many other very well known names from the 1950s. It is one of the most seminal decades for music ever. The 1940s are worse, perhaps because of the war, but still there is Rodgers and Hammerstein, lots of big band, and Woody Guthrie.

Contra Ted Gioia, much of that remains well-known to this day, though I would admit Howard Hanson and Walter Piston have fallen by the wayside. Overall, I think we are processing the American past pretty well.

More corruption in the Harvard leadership

Harvard School of Public Health Dean Andrea A. Baccarelli received at least $150,000 to testify against Tylenol’s manufacturer in 2023 — two years before he published research used by the Trump administration to link the drug to autism, a connection experts say is tenuous at best.

Baccarelli served as an expert witness on behalf of parents and guardians of children suing Johnson & Johnson, the manufacturer of Tylenol at the time. U.S. District Court Judge Denise L. Cote dismissed the case last year due to a lack of scientific evidence, throwing out Baccarelli’s testimony in the process.

“He cherry-picked and misrepresented study results and refused to acknowledge the role of genetics in the etiology” of autism spectrum disorder or ADHD, Cote wrote in her decision, which the plaintiffs have since appealed.

Here is more from The Crimson.

Why we should not auction off all H1-B visas

I am fine with auctioning off some of them, but it should not be the dominant allocation mechanism. The visas work best when they support young talents who are unproven and perhaps liquidity constrained. Sundar Pichai was not a big star when he received his H1-B.

How about the business paying? Well, that is hard for a lot of start-ups. McKinsey, the employer who got Sundar his visa, might have coughed up the 100k, but Sundar did not stay there very long, only about two years. Which is what you might expect from the most talented, upwardly mobile candidates. That will discourage even well-capitalized businesses from making these investments, or they might try to lock in their new hires more than is currently the case.

So a pure auction mechanism probably is not optimal here, even though again it is fine to auction off some of the slots.

Wednesday assorted links

2. Cass Sunstein on liberalism (New Yorker). Often Chotiner interviews are very good, but this one I felt was quite unfair, the cancel culture game all over again. Cass praises Hayek, and Chotiner responds by noting a poor and apparently racist attitude of Hayek’s. If someone said they were a Keynesian economist, would your first reaction be to ask about Keynes’s anti-Semitism? Especially in a short interview. Chotiner also uses the spousal card against Cass, and Cass’s unwillingness to speak ill of a dead acquaintance (and yes that is the right word here) against him. So I expect better than this.

3. WSJ covers Thiel on the Antichrist. Some of the theologians do not like the competition.

4. NFL teams are punting less (WSJ). As economists have been recommending for some while.

AI and the FDA

Dean Ball has an excellent survey of the AI landscape and policy that includes this:

The speed of drug development will increase within a few years, and we will see headlines along the lines of “10 New Computationally Validated Drugs Discovered by One Company This Week,” probably toward the last quarter of the decade. But no American will feel those benefits, because the Food and Drug Administration’s approval backlog will be at record highs. A prominent, Silicon Valley-based pharmaceutical startup will threaten to move to a friendlier jurisdiction such as the United Arab Emirates, and they may in fact do it.

Eventually, I expect the FDA and other regulators to do something to break the logjam. It is likely to perceived as reckless by many, including virtually everyone in the opposite party of whomever holds the White House at the time it happens. What medicines you consume could take on a techno-political valence.

Agreed—but the nearer-term upside is repurposing. Once a drug has been FDA approved for one use, physicians can prescribe it for any use. New uses for old drugs are often discovered, so the off-label market is large. The key advantage of off-label prescribing is speed: a new use can be described in the medical literature and physicians can start applying that knowledge immediately, without the cost and delay of new FDA trials. When the RECOVERY trial provided evidence that an already-approved drug, dexamethasone, was effective against some stages of COVID, for example, physicians started prescribing it within hours. If dexamethasone had had to go through new FDA-efficacy trials a million people would likely have died in the interim. With thousands of already approved drugs there is a significant opportunity for AI to discover new uses for old drugs. Remember, every side-effect is potentially a main effect for a different condition.

On Ball’s main point, I agree: there is considerable room for AI-discovered drugs, and this will strain the current FDA system. The challenge is threefold.

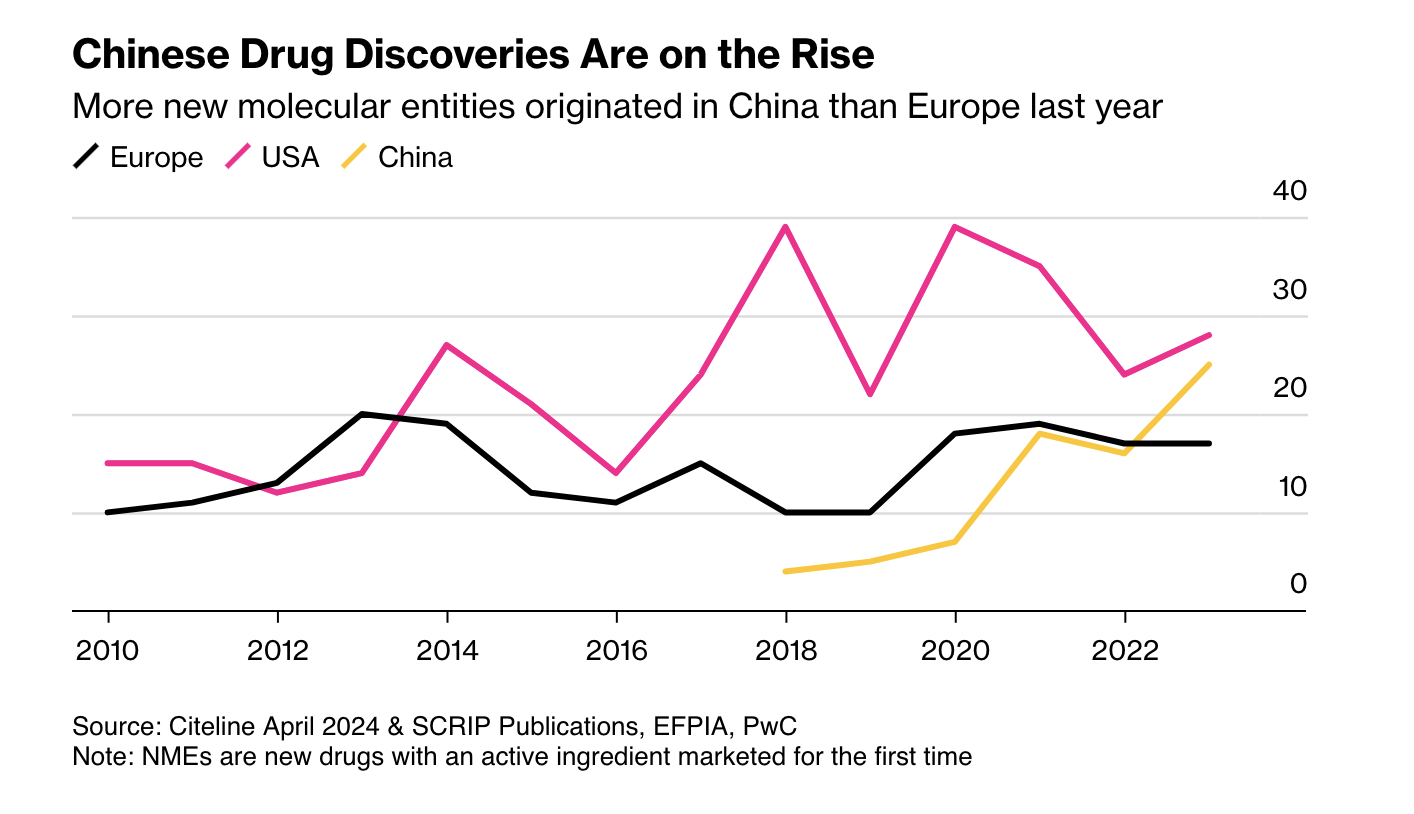

First, as Ball notes, more candidate drugs at lower cost means other regulators may become competitive with the FDA. China is the obvious case: it is now large and wealthy enough to be an independent market, and its regulators have streamlined approvals and improved clinical trials. More new drugs now emerge from China than from Europe.

Second, AI pushes us toward rational drug design. RCTs were a major advance, but they are in some sense primitive. Once a mechanic has diagnosed a problem, the mechanic doesn’t run a RCT to determine the solution. The mechanic fixes the problem! As our knowledge of the body grows, medicine should look more like car repair: precise, targeted, and not reliant on averages.

Closely related is the rise of personalized medicine. As I wrote in A New FDA for the Age of Personalized, Molecular Medicine:

Each patient is a unique, dynamic system and at the molecular level diseases are heterogeneous even when symptoms are not. In just the last few years we have expanded breast cancer into first four and now ten different types of cancer and the subdivision is likely to continue as knowledge expands. Match heterogeneous patients against heterogeneous diseases and the result is a high dimension system that cannot be well navigated with expensive, randomized controlled trials. As a result, the FDA ends up throwing out many drugs that could do good.

RCTs tell us about average treatment effects, but the more we treat patients as unique, the less relevant those averages become.

AI holds a lot of promise for more effective, better targeted drugs but the full promise will only be unlocked if the FDA also adapts.

Michael Clemens on H1-B visas

From 1990 to 2010, rising numbers of H-1B holders caused 30–50 percent of all productivity growth in the US economy. This means that the jobs and wages of most Americans depend in some measure on these workers.

The specialized workers who enter on this visa fuel high-tech, high-growth sectors of the 21st century economy with skills like computer programming, engineering, medicine, basic science, and financial analysis. Growth in those sectors sparks demand for construction, food services, child care, and a constellation of other goods and services. That creates employment opportunities for native workers in all sectors and at all levels of education.

This is not from a textbook narrative or a computer model. It is what happened in the real world following past, large changes in H-1B visa restrictions. For example, Congress tripled the annual limit on H-1B visas after 1998, then slashed it by 56 percent after 2004. That produced large, sudden shocks to the number of these workers in some US cities relative to others. Economists traced what happened to various economic indicators in the most-affected cities versus the least-affected but otherwise similar cities. The best research exhaustively ruled out other, confounding forces.

That’s how we know that workers on H-1B visas cause dynamism and opportunity for natives. They cause more patenting of new inventions, ideas that create new products and even new industries. They cause entrepreneurs to found more (and more successful) high-growth startup firms. The resulting productivity growth causes more higher-paying jobs for native workers, both with and without a college education, across all sectors. American firms able to hire more H-1B workers grow more, generating far more jobs inside and outside the firm than the foreign workers take.

An important, rigorous new study found the firms that win a government lottery allowing them to hire H-1B workers produce 27 percent more than otherwise-identical firms that don’t win, employing more immigrants but no fewer US natives—thus expanding the economy outside their own walls. So, when an influx of H-1B workers raised a US city’s share of foreign tech workers by 1 percentage point during 1990–2010, that caused7 percent to 8 percent higher wages for college-educated workers and 3 percent to 4 percent higher wages for workers without any college education.

Here is the full piece.

What should I ask Sam Altman?

I will be having a conversation with him at a Roots of Progress event, though it will not be a formal CWT Conversation per se. So what should I ask him?

To be clear, this is the conversation with Sam I want to have…

Tuesday assorted links

1. Do you want to own a share of a Rembrandt?

2. Is mid-20th century American culture getting erased? To be clear, I do not find all of that work to be so great. It is for “people like me,” and that is fine, but much of it does not deserve to survive more generally.

4. Toward an AI-augmented textbook.

5. Biting each others’ ankles over who will be the greater fool.

6. “First known wild ‘grue jay’ hybrid spotted in Texas.” An evolutionary reunion of sorts…

The Return of the MR Podcast: In Praise of Commercial Culture

The Marginal Revolution Podcast is back with new episodes! We begin with what I think is our best episode to date. We revisit Tyler’s 1998 book In Praise of Commercial Culture. This is the book that put Tyler on the map as a public intellectual. Tyler and I also wrote a paper, An Economic Theory of Avant-Garde and Popular Art, or High and Low Culture, exploring themes from the book. But does In Praise of Commercial Culture stand the test of time? You be the judge!

The Marginal Revolution Podcast is back with new episodes! We begin with what I think is our best episode to date. We revisit Tyler’s 1998 book In Praise of Commercial Culture. This is the book that put Tyler on the map as a public intellectual. Tyler and I also wrote a paper, An Economic Theory of Avant-Garde and Popular Art, or High and Low Culture, exploring themes from the book. But does In Praise of Commercial Culture stand the test of time? You be the judge!

Here’s one bit:

TABARROK: Here’s a quote from the book, “Art and democratic politics, although both beneficial activities, operate on conflicting principles.”

COWEN: So much of democratic politics is based on consensus. So much of wonderful art, especially new art, is based on overturning consensus, maybe sometimes offending people. All this came to a head in the 1990s, disputes over what the National Endowment for the Arts in America was funding. Some of it, of course, was obscene. Some of it was obscene and pretty good. Some of it was obscene and terrible.

What ended up happening is the whole process got bureaucratized. The NEA ended up afraid to make highly controversial grants. They spend more on overhead. They send more around to the states. Now, it’s much more boring. It seems obvious in retrospect. The NEA did a much better job in the 1960s, right after it was founded, when it was just a bunch of smart people sitting around a table saying, “Let’s send some money to this person,” and then they’d just do it, basically.

TABARROK: Right, so the greatness cannot survive the mediocrity of democratic consensus.

COWEN: There are plenty of good cases where government does good things in the arts, often in the early stages of some process before it’s too politicized. I think some critics overlook that or don’t want to admit it.

TABARROK: One of the interesting things in your book was that the whole history of the NEA, this recreates itself, has recreated itself many times in the past. The salon during the French painting Renaissance, the impressionists hated the salon, right?

COWEN: Right. And had typically turned them away because the works weren’t good enough.

TABARROK: There could be rent-seeking going on, right? The artists get control. Sometimes it’s democratic politics, but sometimes it’s some clique of artists who get control and then funnel the money to their friends.

COWEN: French cinematic subsidies would more fit that latter model. It’s not so much that the French voters want to pay for those movies, but a lot of French government is controlled by elites. The elites like a certain kind of cinema. They view it as a counterweight to Hollywood, preserving French culture. The French still pay for or, indirectly by quota, subsidize a lot of films that just don’t really even get released. They end up somewhere and they just don’t have much impact flat out.

Here’s the episode. Subscribe now to take a small step toward a much better world: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube.

Girls improve student mental health

Using individual-level data from the Add Health surveys, we leverage idiosyncratic variation in gender composition across cohorts within the same school to examine whether being exposed to a higher share of female peers affects mental health and school satisfaction. We find that being exposed to a higher proportion of female peers, despite only improving school satisfaction for boys, improves mental health for both boys and girls. The benefits are greater among boys of low socioeconomic backgrounds, who would otherwise be more likely to be exposed to violent and disruptive peers. We find suggestive evidence that the mechanisms driving our findings are consistent with stronger school friendships for boys and better self-image and grades for girls.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Monica Deza and Maria Zhu.