Thursday assorted links

1. What do economists know about the Black Death?

2. Topol and Offit on vaccines. Excellent material, but it is striking how conservative Offit is when it comes to means of responsibly accelerating knowledge about vaccines. Not a peep about market incentives, for one thing. WWJBS?

3. More detail on the Taiwanese Covid response, especially from the tech side.

4. “…which includes work on the rhetorical strategies of far-right groups.”

5. Super recognisers, recommended.

6. Using AlphaZero (and Kramnik) to invent new forms of chess.

Evidence from 27 Thousand Economics Journal Articles on Africa

The first two decades of the 21st century have seen an increasing number of peer-reviewed journal articles on the 54 countries of Africa by both African and non-African economists. I document that the distribution of research across African countries is highly uneven: 45% of all economics journal articles and 65% of articles in the top five economics journals are about five countries accounting for just 16% of the continent’s population. I show that 91% of the variation in the number of articles across countries can be explained by a peacefulness index, the number of international tourist arrivals, having English as an official language, and population. The majority of research is context-specific, so the continued lack of research on many African countries means that the evidence base for local policy-makers is much smaller in these countries.

Here is the article by Obie Porteus, via David Evans.

Those new service sector jobs, coffin whisperer edition

Also known as markets in everything:

Bill Edgar has, in his own words, “no respect for the living”. Instead, his loyalty is to the newly departed clients who hire Mr Edgar — known as “the coffin confessor” — to carry out their wishes from beyond the grave.

Mr Edgar runs a business in which, for $10,000, he is engaged by people “knocking on death’s door” to go to their funerals or gravesides and reveal the secrets they want their loved ones to know.

“They’ve got to have a voice and I lend my voice for them,” Mr Edgar said.

Mr Edgar, a Gold Coast private investigator, said the idea for his graveside hustle came when he was working for a terminally ill man.

“We got on to the topic of dying and death and he said he’d like to do something,” Mr Edgar said.

“I said, ‘Well, I could always crash your funeral for you’,” and a few weeks later the man called and took Mr Edgar up on his offer and a business was born.

In almost two years he has “crashed” 22 funerals and graveside events, spilling the tightly-held secrets of his clients who pay a flat fee of $10,000 for his service.

And:

In the case of his very first client Mr Edgar said he was instructed to interrupt the man’s best friend when he was delivering the eulogy.

“I was to tell the best mate to sit down and shut up,” he said.

“I also had to ask three mourners to stand up and to please leave the service and if they didn’t I was to escort them out.

“My client didn’t want them at his funeral and, like he said, it is his funeral and he wants to leave how he wanted to leave, not on somebody else’s terms.”

Despite the confronting nature of his job, Mr Edgar said “once you get the crowd on your side, you’re pretty right” because mourners were keen to know what was left unsaid.

You might think “that’s it,” but no the article is interesting throughout. For the pointer I thank Daniel Dummer.

Wednesday assorted links

1. In honor of Assar Lindbeck.

2. The Biden health care plan.

3. How many votes get lost through the mail? (link now fixed)

4. Hummingbird torpor. Has implications for the parrot skit, they really are “pining for the fjords”!

5. Thread on estimating persistence. No one seems to be rebutting this critique with any effectiveness.

My Conversation with Matt Yglesias

Substantive, interesting, and fun throughout, here is the audio, video, and transcript. For more do buy Matt’s new book One Billion Americans: The Case for Thinking Bigger. Here is the CWT summary:

They discussed why it’s easier to grow Tokyo than New York City, the governance issues of increasing urban populations, what Tyler got right about pro-immigration arguments, how to respond to declining fertility rates, why he’d be happy to see more people going to church (even though he’s not religious), why liberals and conservatives should take marriage incentive programs more seriously, what larger families would mean for feminism, why people should read Robert Nozick, whether the YIMBY movement will be weakened by COVID-19, how New York City will bounce back, why he’s long on Minneapolis, how to address constitutional ruptures, how to attract more competent people to state and local governments, what he’s learned growing up in a family full of economists, his mother’s wisdom about visual design and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Now, I think people, on average, should become more religious, in part because that would encourage fertility. Do you also think people should become more religious?

YGLESIAS: Yeah, if I could be full Straussian and kind of —

COWEN: You can be! It’s not a hypothetical.

YGLESIAS: [laughs] No. I don’t really know how to do it. If I put in my book that I think we should make people be more religious, I don’t know how I would do that.

COWEN: Not make them, but just root for it. Talk up religion.

YGLESIAS: Look, if you told me, for mysterious reasons, church attendance is going to start going back up again over the next 30, 40 years, I would consider that to be a very optimistic forecast for America. I think good secondary things would follow from that. I think community institutions are important, and in a practical sense, religious ones are what seems to really work for people.

When I hear people say, “Oh this new woke anti-racism on the left — that’s like a new religion.” I don’t know that that’s 100 percent accurate. I think there’s something to that, and there’s also ways in which it’s not true.

But if it was really literally true — this is a new religion where people are going to get together once a week, and they’re going to know each other, and they’re going to have a higher value system that motivates them, and they’re going to make connections — that would be really good. Bad things have happened by religious people or under religious causes, but generally speaking, it’s good when people go to church.

COWEN: If you’re rooting for a more religious America, does that mean, in a sense, you’re rooting for a more right-wing America? These are correlated, right? Causality may be tricky, but I suspect there is some.

YGLESIAS: I think probably we say that religiousness is almost constitutive of right-wingy-ness, at least in some definitions. Yeah, I think a more traditionalist America, in some ways, would be good.

It was so much fun we even ran over the allotted time, we had to discuss Gilbert Arenas too.

Failing the Challenge

CNN says “In one word, this is why there likely won’t be a vaccine available before Election Day: biology.” Wrong. The one word is complacency. What CNN refers to as biology is the time it takes to run clinical trials.

Here’s how the trials work: You take 30,000 people, give half of them a vaccine and half of them a placebo, which is a shot of saline that does nothing. Then those 30,000 people go about their lives, and you wait to see how many in each group become infected and sick with Covid-19, the “endpoint” in medical parlance.

That waiting takes time, especially since the coronavirus vaccines currently being studied in the US are two-dose vaccines with each dose several weeks apart.

But it gets worse because trial volunteers are not random:

“Who’s in the trials – the kind of people who tend to stay at home or the kind of people who attended the Sturgis rally?” said John Moore, an immunologist at Weill Cornell Medicine, referring to a motorcycle rally in South Dakota that led to at least dozens of cases of Covid-19.

Historical precedent, as well as the demographics of the participants in the current coronavirus vaccine trials, suggest more the stay-at-home type.

That does not bode well for bringing the trials to a speedy conclusion.

Typically, those who volunteer for clinical trials tend to be “White, college-educated women,” said Frenck, who has been the principal investigator on dozens of vaccine clinical trials, and has served on the Data and Safety Monitoring Board for many others.

All three of those factors are potentially bad news for the coronavirus clinical trials, because data indicates White college-educated women are at lower risk for being exposed to the novel coronavirus.

None of this, however, is actually about biology. It’s about complacency. We could have run human challenge trials and paid for diverse volunteers but we decided that was too risky or too new or too radical or too something and so thousands of people die every week as we wait.

Addendum: Previous posts on challenge trials.

Not how things work any more may the great Gerald Shur rest in peace

The recently deceased Gerald Shur set up and then ran the Witness Protection Program:

“No witnesses got protection without his personal attention,” Pete Earley, co-author with Mr. Shur of the book “WITSEC: Inside the Federal Witness Protection Program” (2002), wrote in a tribute to Mr. Shur.

“He wrote nearly all of the program’s rules, shaped it based on his own personal philosophical views, and guided it with an iron hand. He helped create false backgrounds, arranged secret weddings, oversaw funerals. He personally persuaded corporate executives to hire a mafia hit man as a delivery route driver, once arranged for the wife of a Los Angeles killer to have breast enlargement surgery to keep her husband happy, and got the government to pay for a penile implant for one mobster turned witness after he became depressed.

“In return,” Earley continued, “WITSEC witnesses helped topple the heads of every major crime family in every major city, helping send ten thousand criminals to prison because of their testimonies.”

Here is the WaPo obituary for Shur. What would a bureaucratically stifled Shur be doing today? Working in the private sector perhaps? Here is the NYT obituary as well.

*Where is my flying car?: A memoir of future past*, by J. Storrs Hall

Who is this guy? How come no one told me about this book until Adam Ozimek asked about it?

One of the main arguments of the book is that we could have had major technological advances in multiple areas if only we had put in another fifty years of hard work on them. Flying cars could have been a thing some time ago!

The author estimates that if quality nanotechnology were up and running, it would take only about a week to rebuild the entire United States. Just imagine how silly the current building permit system would seem then.

The anecdotes on the history of helicopters are interesting and obsessive in a good way.

One of the arguments is simply that we have not much succeeded in boosting our aggregate use of energy. Hall also argues we do not face sufficient challenges, in part because nuclear deterrence has worked so well.

An editor would not approve of the organization and rambling structure of this book, including the lengthy digressions on technologies of the author’s choice and fascination. It does not bother me.

Here is one short bit, not actually representative of the basic style, but I enjoyed it anyway:

If you are a technologist working on some new, clean, abundant form of energy, I wish you all the luck in the world. But you must not labor under the illusion that should you succeed, your efforts will be justly rewarded by the gratitude of the people you have lifted from poverty and enabled to have a bright and growing future. You will be attacked, your work will be lied about by activists, demonized by ignorant journalists, and strangled by regulation.

But only if it works.

You can buy it here, Kindle only for $3.14, note it is a full-length book with all the proper trappings. It’s one of the best and most interesting books on technology in some time, either ignore or enjoy the organizational infelicities, first published in 2018.

The Fractured-Land Hypothesis

From Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, Mark Koyama, Youhong Lin, and Tuan-Hwee Sng, here is a new NBER working paper:

Patterns of political unification and fragmentation have crucial implications for comparative economic development. Diamond (1997) famously argued that “fractured land” was responsible for China’s tendency toward political unification and Europe’s protracted political fragmentation. We build a dynamic model with granular geographical information in terms of topographical features and the location of productive agricultural land to quantitatively gauge the effects of “fractured land” on state formation in Eurasia. We find that either topography or productive land alone is sufficient to account for China’s recurring political unification and Europe’s persistent political fragmentation. The existence of a core region of high land productivity in Northern China plays a central role in our simulations. We discuss how our results map into observed historical outcomes and assess how robust our findings are.

Here is a 15-minute video associated with the paper.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Brazzaville. Photos.

2. MIE: Monetizing the physiological data of squash players. And the market doesn’t like it when journalists are killed.

3. Why Karachi floods. And why are so many in Karachi asymptomatic?

4. You can’t call them neurotics if all of them are.

5. NYT covers Nakamura playing blitz chess on Twitch. And coverage from The Conversation. Magnus is number one anyway, so it is Nakamura who is the big winner from this new regime, and Caruana — who is now “just another very good player” — who is the big loser.

6. For better or worse, those “Big Pharma” companies do not seem to have pledged anything concrete about not accelerating Phase 3 for their vaccine trials. It is amazing how gullible the intelligent world has become, if only a story makes them feel more intelligent, especially relative to you-know-who.

Does Demand for New Currencies Increase in a Recession?

Every time there is a recession we hear more about barter and new currencies, especially so-called “local” currencies. An inceased interest in barter and new currencies suggests a theory of recessions, the lack of liquidity theory:

Bloomberg: “In times of crisis like the one we are jumping into, the main issue is lack of liquidity, even when there is work to be done, people to do it, and demand for it,” says Paolo Dini, an associate professorial research fellow at the London School of Economics and one of the world’s foremost experts on complementary currencies. “It’s often a cash flow problem. Therefore, any device or instrument that saves liquidity helps.”

I wrote about this several years ago but on closer inspection it’s not obvious that interest in barter or new currencies increases much in a recession or that these new currencies are helpful. Here’s my previous post (with a new graph) and no indent.

Nick Rowe explains that the essence of New Keynesian/Monetarist theories of recessions is the excess demand for money (Paul Krugman’s classic babysitting coop story has the same lesson). Here’s Rowe:

The unemployed hairdresser wants her nails done. The unemployed manicurist wants a massage. The unemployed masseuse wants a haircut. If a 3-way barter deal were easy to arrange, they would do it, and would not be unemployed. There is a mutually advantageous exchange that is not happening. Keynesian unemployment assumes a short-run equilibrium with haircuts, massages, and manicures lying on the sidewalk going to waste. Why don’t they pick them up? It’s not that the unemployed don’t know where to buy what they want to buy.

If barter were easy, this couldn’t happen. All three would agree to the mutually-improving 3-way barter deal. Even sticky prices couldn’t stop this happening. If all three women have set their prices 10% too high, their relative prices are still exactly right for the barter deal. Each sells her overpriced services in exchange for the other’s overpriced services….

The unemployed hairdresser is more than willing to give up her labour in exchange for a manicure, at the set prices, but is not willing to give up her money in exchange for a manicure. Same for the other two unemployed women. That’s why they are unemployed. They won’t spend their money.

Keynesian unemployment makes sense in a monetary exchange economy…it makes no sense whatsoever in a barter economy, or where money is inessential.

Rowe’s explanation put me in mind of a test. Barter is a solution to Keynesian unemployment but not to “RBC unemployment” which, since it is based on real factors, would also occur in a barter economy. So does barter increase during recessions?

There was a huge increase in barter and exchange associations during the Great Depression with hundreds of spontaneously formed groups across the country such as California’s Unemployed Exchange Association (U.X.A.). These barter groups covered perhaps as many as a million workers at their peak.

In addition, I include with barter the growth of alternative currencies or local currencies such as Ithaca Hours or LETS systems. The monetization of non-traditional assets can alleviate demand shocks which is one reason why it’s good to have flexibility in the definition of and free entry into the field of money (a theme taken up by Cowen and Kroszner in Explorations in New Monetary Economics and also in the free banking literature.)

During the Great Depression there was a marked increase in alternative currencies or scrip, now called depression scrip. In fact, Irving Fisher wrote a now forgotten book called Stamp Scrip. Consider this passage and note how similar it is to Nick’s explanation:

If proof were needed that overproduction is not the cause of the depression, barter is the proof – or some of the proof. It shows goods not over-produced but dead-locked for want of a circulating transfer-belt called “money.”

Many a dealer sits down in puzzled exasperation, as he sees about him a market wanting his goods, and well stocked with other goods which he wants and with able-bodied and willing workers, but without work and therefore without buying power. Says A, “I could use some of B’s goods; but I have no cash to pay for them until someone with cash walks in here!” Says B, “I could buy some of C’s goods, but I’ve no cash to do it with till someone with cash walks in here.” Says the job hunter, “I’d gladly take my wages in trade if I could work them out with A and B and C who among them sell the entire range of what my family must eat and wear and burn for fuel – but neither A nor B nor C has need of me – much less could the three of them divide me up.” Then D comes on the scene, and says, “I could use that man! – if he’d really take his pay in trade; but he says he can’t play a trombone and that’s all I’ve got for him.”

“Very well,” cries Chic or Marie, “A’s boy is looking for a trombone and that solves the whole problem, and solves it without the use of a dollar.

In the real life of the twentieth century, the handicaps to barter on a large scale are practically insurmountable….

Therefore Chic or somebody organizes an Exchange Association… in the real life of this depression, and culminating apparently in 1933, precisely what I have just described has been taking place.

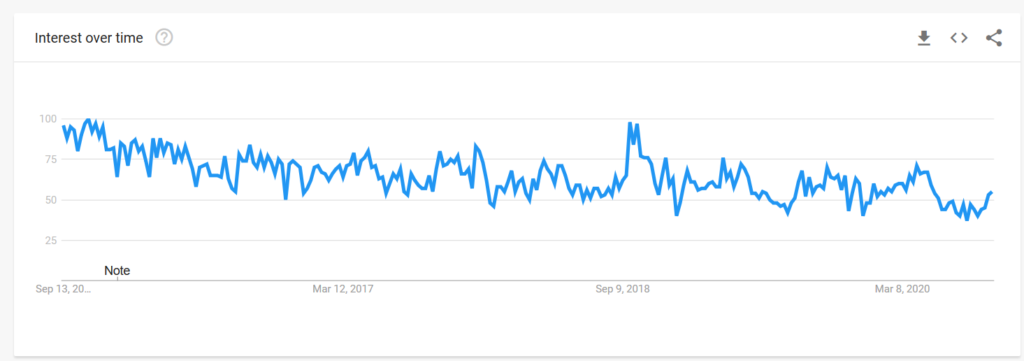

What about today (2011)? Unfortunately, the IRS doesn’t keep statistics on barter (although barterers are supposed to report the value of barter exchanges). Google Trends shows an increase in searches for barter in 2008-2009 but the increase is small. Some reports say that barter is up but these are isolated (see also the 2020 Bloomberg piece), I don’t see the systematic increase we saw during the Great Depression. I find this somewhat surprising as the internet and barter algorithms have made barter easier.

In terms of alternative currencies, the best data that I can find shows that the growth of alternative currencies in the United States is small, sporadic and not obviously increasing with the recession. (Alternative currencies are better known in Germany and Argentina perhaps because of the lingering influence of Heinrich Rittershausen and Silvio Gesell).

Below is a similar graph for 2017-2020. Again not much increase in recent times.

In sum, the increase in barter and scrip during the Great Depression is supportive of the excess demand for cash explanation of that recession, even if these movements didn’t grow large enough, fast enough to solve the Great Depression. Today there seems to be less interest in barter and alternative currencies than expected, or at least than I expected, given an AD shock and the size of this recession. I don’t draw strong conclusions from this but look forward to further research on unemployment, recessions and barter.

What I’ve been reading

1. Stephen Hough, Rough Ideas: Reflections on Music and More. Scattered tidbits, about half of them very interesting, most of the rest at least decently good, mostly for fans of classical music and piano music. Should you develop the habit of warming up? Why don’t they always have a piano in the “green room”? How many recordings should you sample before trying to play a piece? What kinds of relationships do pianists develop with their page turners? That sort of thing. I read the whole thing.

2. Jeremy England, Every Life is on Fire: How Thermodynamics Explains the Origins of Living Things. A fun and readable popular science book on why life may be likely to evolve from inanimate matter: “Living things…make copies of themselves, harvest and consume fuel, and accurately predict the surrounding environment.” Who could be against that?

3. Dov H. Levin, Meddling in the Ballot Box: The Causes and Effects of Partisan Electoral Interventions. “A fifth significant way in which the U.S. aided Adenauer’s reelection was achieved by Dulles publicly threatening, in an American press conference which took place two days before the elections, “disastrous effects” for Germany if Adenauer was not reelected.” A non-partisan, academic work, “This study is the first book-length study of partisan electoral interventions as a discrete, stand-alone phenomenon.” From 1946-2000, there were 81 discrete U.S. interventions in foreign elections, and 36 by the USSR/Russia, noting that outright conquest did not count in that data base.

4. John Kampfner, Why the Germans Do it Better: Notes from a Grown-Up Country (UK Amazon link, not yet in the USA). You should dismiss the title altogether, which is intended to provoke British people. In fact the author spends plenty of time on what is wrong with Germany, ranging from an incoherent foreign policy to the weaknesses of Frankfurt as a financial center. In any case, this is an excellent book trying to lay out and explain recent German politics and economics. It is more conventional wisdom than daring hypothesis, but the conventional wisdom is very often correct and how many people really know the conventional wisdom about Naomi Seibt anyway? Recommended, the best recent look at what is still one of the world’s most important countries.

5. David Carpenter, Henry III: 1207-1258. “No King of England came to the throne in a more desperate situation than Henry III.” The Magna Carta had just been instituted, Henry was just nine years old, and England was ruled by a triumvirate, with a very real chance that the French throne would swallow up England. This is one of those “has a lot of unfamiliar names that are hard to keep track of” books, but don’t blame Carpenter for that. In terms of scholarly contribution it stands amongst the very top books of the year. And yes there was already a Wales back then. They also started building Westminster Abbey under Henry’s reign. Here are some of the origins of state capacity libertarianism, volume II is yet to come.

6. Elena Ferrante, The Lying Life of Adults. The last quarter of the book closes strong, so my final assessment is enthusiastic, even if it isn’t in the exalted league of her Neapolitan quadrology. It will probably be better upon a rereading, which I will do.

Not your grandpa’s South Asia libertarianism

I did an Ask Me Anything for the South Asian chapter of Students for Liberty, based on their reading of my book Big Business: Love Letter to an American Anti-Hero.

By far the two most popular topics for questions were a) social media, and b) sexual harassment. Understandable, given South Asian circumstances, but not necessarily what you would hear in the United States, especially from an SfL group.

I think most Western libertarians and classical liberals still do not understand how much South Asia is going to redefine their discourse.

Monday assorted links

1. Might changes in proton density, spurred by solar wind, predict earthquakes? If true, this would really be something.

2. Violates Godwin’s Law right upfront anyway speak for yourself! I genuinely find such hostile intentions difficult to understand.

3. Will a growth drug undermine “dwarf pride”? (NYT).

4. Robin Hanson on how and why remote work will matter.

5. Economics of the energy transition. Some subtle and underpromoted points in this one.

6. Why we can’t have good things: I am not sure how much public health experts are to blame for the problems in this article about why we don’t have home testing. The FDA won’t approve it? Do something about that! (Where is the outcry, other than from Paul Romer?) The American people aren’t ready for it? Well, are they ready for the alternatives you are proposing? Overall I found this NYT piece a depressing sign of American and perhaps also public health malaise.

7. Using banned cell phones for prison extortion by calling loved ones back home, excellent NYT piece, amazing investigative journalism.

*Tenet* — a review (no real spoilers)

Although liquid securities markets play no role in the plot, this is nonetheless a movie where the value of information is repeatedly very high.

You can think of the movie as constructing a world so that a high value for information is ruling all of the time. And how strange such a world would have to look.

Most plots are about effort, character, moral fortitude, luck, or preexisting conditions (“are they really meant for each other?”). It is about time we had a film about information, even though the final world that is built is stranger than you might have expected.

“We must go now.”

But in fact, in the real world, you hardly ever need to “go now.” You can go just a little bit later, and it won’t matter much.

But this is not the speed premium, rather the game-theoretic concept is that of last mover advantage, the opposite of Schelling’s first mover advantage. Few of us are intuitively ready to take that concept literally and to order our understanding of a movie around it.

If you have studied Steven Bram’s book Biblical Games (and his other writings), this film will flow naturally for you — otherwise not!

Unlike most slacker films, this movie takes a decided stance on Newcomb’s Paradox, though to reveal that would be a total spoiler.

The movie also has genuine innovations in its chase and fight scenes, a rarity and indeed near-impossibility these days.

The soundtrack is excellent, and might at least some of the music be palindromic?

As for inspirations, you might consider Raiders of the Lost Ark, most other Nolan movies, the Book of Exodus, the Sator Square, James Bond, Frank Tipler and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and most of all Buster Keaton’s Sherlock, Jr.

To be clear, I don’t love most of Nolan’s films, and Inception bored me, so I wasn’t expecting much from Tenet. I walked away happy.

Should I now be rooting for a sequel? Or would that be a prequel?

Kudos to Alex for renting out the theater, he is the real Protagonist is this one.