Tuesday assorted links

1. Various Medicaid budget dilemmas (NYT). A lot is at stake here, though since there are no major personalities involved, this and related stories is not getting much coverage.

2. New claims about string theory.

3. America underestimates the difficulty of bringing manufacturing back.

5. Rationalism vs. empiricism in the AI debates, and how economists fit in.

Manufacturing and Trade

It has become popular in some circles to argue that trade—or, in the more “sophisticated” version, that the dollar’s reserve-currency status—undermines U.S. manufacturing. In reality, there is little support for this claim.

Let’s begin with some simple but often overlooked points.

- The US is a manufacturing powerhouse. We produce $2.5 trillion of value-added in manufacturing output, more than ever before in history.

- As a share of total employment, employment in manufacturing is on a long-term, slow, secular trend down. This is true not just in the United States but in most of the world and is primarily a reflection of automation allowing us to produce more with less. Even China has topped out on manufacturing employment.

- A substantial majority of US imports are for intermediate goods like capital goods, industrial supplies and raw materials that are used to produce other goods including manufacturing exports! Tariffs, therefore, often make it more costly to manufacture domestically.

- The US is a big country and we consume a lot of our own manufacturing output. We do export and import substantial amounts, but trade is not first order when it comes to manufacturing. Regardless of your tariff theories, to increase manufacturing output we need to increase US manufacturing productivity by improving infrastructure, reducing the cost of energy, improving education, reducing regulation and speeding permitting. You can’t build in America if you can’t build power plants, roads and seaports.

- The US is the highest income large country in the world. It’s hard to see how we have been ripped off by trade. China is much poorer than the United States.

- China produces more manufacturing output than the United States, most of which it consumes domestically. China has more than 4 times the population of the United States. Of course, they produce more! India will produce more than the United States in the future as well. Get used to it. You know what they say about people with big shoes? They have big feet. Countries with big populations. They produce a lot. More Americans would solve this “problem.”

- Most economists agree that there are some special cases for subsidizing and protecting a domestic industry, e.g. military production, vaccines.

The seven points cover most of the ground but more recently there has been an argument that the US dollar’s status as a reserve currency, which we used to call the “exorbitant privilege,” is now somehow a nefarious burden. This strikes me as largely an ex-post rationalization for misguided policies, but let’s examine the core claim: the US’s status as a reserve currency forces the US dollar to appreciate which makes our exports less competitive on world markets. Tariffs are supposed to (somehow?) depreciate the currency solving this problem. Every step is questionable. Note, for example, that tariffs tend to appreciate the dollar since the supply of dollars declines. Note also that if even if tariffs depreciated the currency, depreciating the currency doesn’t help to increase exports if you have cut imports (see Three Simple Principles of Trade Policy). I want to focus, however, on the first point does the US status as world reserve currency appreciate the dollar and hurt exports? This is mostly standard economics so its not entirely wrong but I think it misses key points even for most economists.

Countries hold dollars to facilitate world trade, and this benefits the United States. By “selling” dollars—which we can produce at minimal cost (albeit it does help that we spend on the military to keep the sea lanes open)—we acquire real goods and services in exchange, realizing an “exorbitant privilege.” Does that privilege impose a hidden cost on our manufacturing sector? Not really.

In the short run, increased global demand for dollars can push up the exchange rate, making exports more expensive. Yet this effect arises whatever the cause of the increased demand for dollars. If foreigners want to buy more US tractors this appreciates the dollar and makes it more expensive for foreigners to buy US computers. Is our tractor industry a nefarious burden on our computer industry? I don’t think so but more importantly, this is a short-run effect. Exchange rates adjust first, but other prices follow, with purchasing power parity (PPP) tendencies limiting any long-term overvaluation.

To see why, imagine a global single-currency world (e.g., a gold standard or a stablecoin pegged to the US dollar). In this scenario, increased demand for US assets would primarily lead to lower US interest rates or higher US asset prices, equilibrating the market without altering the relative price of US goods through the exchange rate mechanism. With freely floating exchange rates, the exchange rate moves first and the effect of the increased demand is moderated and spread widely but as other prices adjust the long-run equilibrium is the same as in a world with one currency. There’s no permanent “extra” appreciation that would systematically erode manufacturing competitiveness. Notice also that the moderating effect of floating exchange rates works in both directions so when there is deprecation the initial effect is spread more widely giving industries time to adjust as we move to the final equilibrium.

None of this to deny that some industries may feel short-run pressure from currency swings but these pressures are not different from all of the ordinary ups and down of market demand and supply, some of which, as I hove noted, floating exchange rates tend to moderate.

Ensuring a robust manufacturing sector depends on sound domestic policies, innovation, and workforce development, rather than trying to devalue the currency or curtail trade. Far from being a nefarious cost, the U.S. role as issuer of the world’s reserve currency confers significant financial and economic advantages that, in the long run, do not meaningfully erode the nation’s manufacturing base.

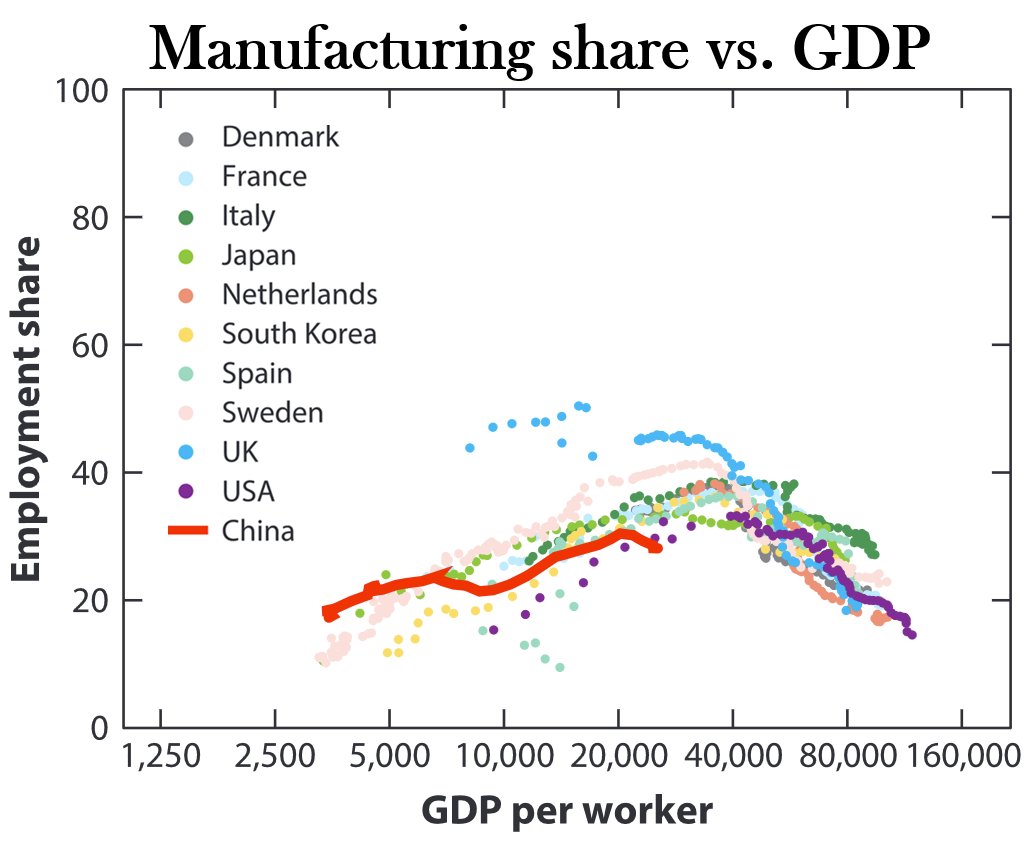

Manufacturing share vs. GDP

Via Basil Halperin. This is not a question of confusing causation and correlation, if anything it is the protectionists who have such an error in their mind’s eye. These days the average U.S. service sector job pays more than a manufacturing job.

My 2022 piece on the New Right vs. classical liberalism

Worth a redux, here is one excerpt:

While I try my best to understand the New Right, I am far from being persuaded. One worry I have is about how it initially negative emphasis feeds upon itself. Successful societies are based on trust, including trust in leaders, and the New Right doesn’t offer resources for forming that trust or any kind of comparable substitute. As a nation-building project it seems like a dead end. If anything, it may hasten the Brazilianification of the United States rather than avoiding it, Brazil being a paradigmatic example of a low trust society and government.

I also do not see how the New Right stance avoids the risks from an extremely corrupt and self-seeking power elite. Let’s say the New Right description of the rottenness of elites were true – would we really solve that problem by electing more New Right-oriented individuals to government? Under a New Right worldview, there is all the more reason to be cynical about New Right leaders, no matter which ideological side they start on. If elites are so corrupt right now, the force corrupting elites are likely to be truly fundamental…

The New Right also seems bad at coalition building, most of all because it is so polarizing about the elites on the other side. Many of the most beneficial changes in American history have come about through broad coalitions, not just from one political side or the other. Libertarians such as William Lloyd Garrison played a key role an anti-slavery debates, but they would not have gotten very far without support from the more statist Republicans, including Abraham Lincoln. If you so demonize the elites that do not belong to your side, it is more likely we will end up in situations where all elites have to preside over a morally unacceptable status quo…

Perhaps most of all, it is dangerous when “how much can we trust elites?” becomes a major dividing line in society. We’ve already seen the unfairness and cascading negativism of cancel culture. To apply cancel culture to our own elites, as in essence the New Right is proposing to do, is not likely to lead to higher trust and better reputations for those in power, even for those who deserve decent reputations.

Recommended, do read or reread the whole thing.

Tariff sentences to ponder

We find that only 15.1 percent of the decline in goods-sector employment from 1992 to 2012 stems from U.S. trade deficits; most of the decline is due to differential productivity growth.

Here is the full paper by Kehoe, Ruhl, and Steinberg, via Zack Mazlish. I believe we have covered this issue before.

One economist removed from the Naval library

Deirdre McCloskey, can you guess which book? See #197. I might add the text to that one is remarkably non-salacious, perhaps many readers were somewhat disappointed.

Via the excellent CW.

Monday assorted links

1. How do people perceive international trade? (redux from a few years ago)

2. Mice exhibit first aid behaviors.

3. What we are learning about the geology of northeastern North America. An interesting piece.

4. Recent ReStud paper on trade imbalances.

5. “Two directors of the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society have been accused of “vandalism” and “mutilation” after allowing furniture designed by the architect to be sawn up and sold for scrap for £80.” Times of London.

6. Is decarbonization a cost center?

7. Arvind Subramanian on Indian music.

8. Magnus and Fabiano analyze their games together.

Mercatus Emerging Scholar initiative

The Emerging Scholars Program is a new initiative of the Mercatus Center, aimed at supporting early-career classical-liberal thinkers who are committed to focusing on an original research project that is well-defined, shows strong potential to further classical liberal ends, and is ready to be started or continued. Through the program, Mercatus will hire a full cohort of scholars for a two-year, paid fellowship based on-site in Arlington, VA.

‘Scholar’ is broadly construed: you might be an academic, but perhaps instead you work in policy, journalism, run a business, or do something entirely different.

‘Emerging’ is also broadly construed: you might be finishing a degree of some kind, but perhaps instead you’re looking to shift focus mid-career, return to public life, or have decided not to retire. Whatever your background, you’ll be a deeply rigorous thinker, working on innovative projects, and excited to share your ideas clearly and broadly, to further classical-liberal ends.

Here is further detail.

Coordination and AI safety (from my email)

Jack Skidmore writes to me, and I will not double indent:

“Hello Tyler,

As someone who follows AI developments with interest (though I’m not a technical expert), I had an insight about AI safety that might be worth considering. It struck me that we might be overlooking something fundamental about what makes humans special and what might make AI risky.

The Human Advantage: Cooperation > Intelligence

- Humans dominate not because we’re individually smartest, but because we cooperate at unprecedented scales

- Our evolutionary advantage is social coordination, not just raw processing power

- This suggests AI alignment should focus on cooperation capabilities, not just intelligence alignment

The Hidden Risk: AI-to-AI Coordination

- The real danger may not be a single superintelligent AI, but multiple AI systems coordinating without human oversight

- AIs cooperating with each other could potentially bypass human control mechanisms

- This could represent a blind spot in current safety approaches that focus on individual systems

A Possible Solution: Social Technologies for AI

- We could develop “social technologies” for AI – equivalent to the norms, values, institutions, and incentive systems that enable human society that promote and prioritize humans

- Example: Design AI systems with deeply embedded preferences for human interaction over AI interaction; or with small, unpredictable variations in how they interpret instructions from other AIs but not from humans

- This creates a natural dependency on human mediation for complex coordination, similar to how translation challenges keep diplomats relevant

Curious your thoughts as someone embedded in the AI world… does this sparks any ideas/seem like a path that is underexplored?”

TC again: Of course it is tricky, because we might be relying on the coordination of some AIs to put down the other, miscreant AIs…

Nikolaus Matthes finishes The Art of the Fugue

Sunday assorted links

1. “15k researchers are working on AGI, in America. We have more people working on AGI then the whole world combined. Be grateful to those researchers putting in 7 day work weeks” Link here.

2. From Glenn: “People still don’t seem to appreciate that official trade figures don’t include the U.S.’ largest “exports” to the world, which is intangible brand/IP/tech that flows via MNCs and aren’t captured in cross-border trade data because the physical products are often produced abroad.”

3. Michael P. Gibson: “If we really want Russia to bleed, you know what we should do? Impose free trade on them. Surely they will wince and holler once free trade makes them worse off. Free trade will hollow out their middle class! Ukraine will have the Donbas again in no time”

3b. Consumer staples were hit hardest by the stock market decline.

4. Owls can swim.

5. Oren Cass has gone entirely in the tank. And more here. I had thought he was preparing to backpedal with his recent “the tariffs have to be predictable to work” Substack. But no. Sad!

5b. p.s. The billionaire oligarchs are not running everything.

6. Roy Foster in conversation with Fintan O’Toole.

7. By now the bloom is off the Luka trade.

Lots of Twitter links today, Twitter had the best stuff.

Why Do Domestic Prices Rise With Tarriffs?

Many people think they understand why domestic prices rise with tariffs–domestic producers take advantage of reduced competition to jack up prices and increase their profits. The explanation seems cynical and sophisticated and its not entirely wrong but it misses deeper truths. Moreover, this “explanation” makes people think that an appropriate response to domestic firms raising prices is price controls and threats, which would make things worse. In fact, tariffs will increase domestic prices even in perfectly competitive industries. Let’s see why.

Suppose we tax imports of French and Italian wine. As a result, demand for California wine rises, and producers in Napa and Sonoma expand production to meet it. Here’s the key point: Expanding production without increasing costs is difficult, especially so for any big expansion in normal times.

To produce more, wine producers in Napa and Sonoma need more land. But the most productive, cost-effective land is already in use. Expansion forces producers onto less suitable land—land that’s either less productive for wine or more valuable for other purposes. Wine production competes with the production of olive oil, dairy and artisanal cheeses, heirloom vegetables, livestock, housing, tourism, and even geothermal energy (in Sonoma). Thus, as wine production expands, costs increases because opportunity costs increase. As wine production expands the price we pay is less production of other goods and services.

Thus, the fundamental reason domestic prices rise with tariffs is that expanding production must displace other high-value uses. The higher money cost reflects the opportunity cost—the value of the goods society forgoes, like olive oil and cheese, to produce more wine.

And the fundamental reason why trade is beneficial is that foreign producers are willing to send us wine in exchange for fewer resources than we would need to produce the wine ourselves. Put differently, we have two options: produce more wine domestically by diverting resources from olive oil and cheese, or produce more olive oil and cheese and trade some of it for foreign wine. The latter makes us wealthier when foreign producers have lower costs.

Tariffs reverse this logic. By pushing wine production back home, they force us to use more costly resources—to sacrifice more olive oil and cheese than necessary—to get the same wine. The result is a net loss of wealth.

Note that tariffs do not increase domestic production, they shift domestic production from one industry to another.

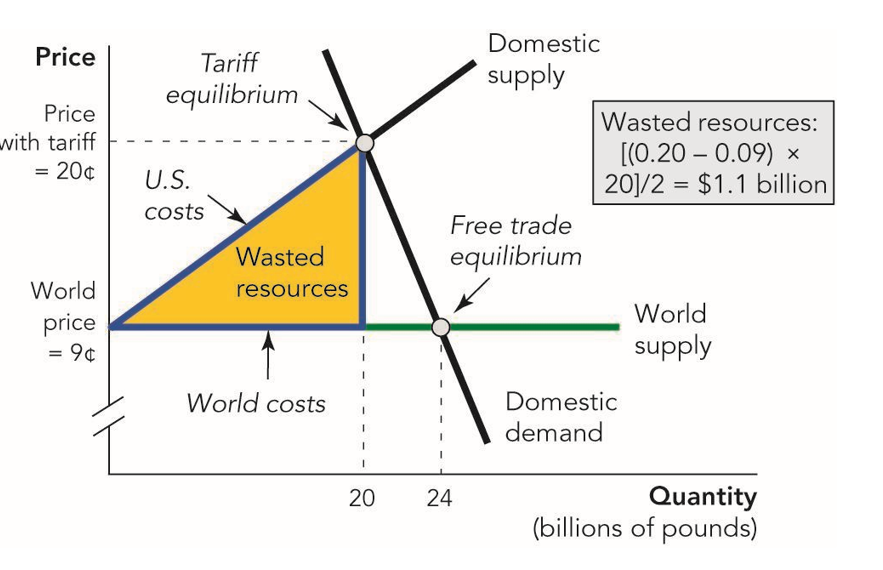

Here’s the diagram, taken from Modern Principles, using sugar as the example. Without the tariff, we could buy sugar at the world price of 9 cents per pound. The tariff pushes domestic production up to 20 billion pounds.

As the domestic sugar industry expands it pulls in resources from other industries. The value of those resources exceeds what we would have paid foreign producers. That excess cost is represented by the yellow area labeled wasted resources—the value of goods and services we gave up by redirecting resources to domestic sugar production instead of using them to produce other goods and services where we have a comparative advantage.

All of this, of course, is explained in Modern Principles, the best textbook for principles of economics. Needed now more than ever.

Five insights from farm animal economics

By Martin Gould, here is one excerpt:

Halting plans for a large, polluting factory farm feels like a clear win — no ammonia-laden air burning residents’ lungs, no waste runoff contaminating local drinking water, and seemingly fewer animals suffering in industrial confinement. But that last assumption deserves scrutiny. What protects one community might actually condemn more animals to worse conditions elsewhere.

Consider the UK: Local groups celebrate blocking new chicken farms. But because UK chicken demand keeps growing — it rose 24% from 2012-2022 — the result of fewer new UK chicken farms is just that the UK imports more chicken: it almost doubled its chicken imports over the same time period. While most chicken imported into the UK comes from the EU, where conditions for chickens are similar, a growing share comes from Brazil and Thailand, where regulations are nonexistent. Blocking local farms may slightly reduce demand via higher prices, but it also risks sentencing animals to worse conditions abroad.

The same problem haunts government welfare reforms — stronger standards in one country can just shift production to places with worse standards. But advocates are getting smarter about this. They’re pushing for laws that tackle both production and imports at once. US states like California have done this — when it banned battery cages, it also banned selling eggs from hens caged anywhere. The EU is considering the same approach. It’s a crucial shift: without these import restrictions, both farm bans and welfare reforms risk exporting animal suffering to places with even worse conditions. And advocates have prioritized corporate policies, which avoid this problem, as companies pledge to stop selling products associated with the worst animal suffering (like caged eggs), regardless of where they are produced.

Russia facts of the day

Russia’s stock market has suffered its worst week in more than two years in response to U.S. President Donald Trump’s sweeping global tariffs and a drop in global oil prices.

The market capitalization of companies listed on the Moscow Exchange (MOEX) fell by 2 trillion rubles ($23.7 billion) over just two days, sliding from 55.04 trillion rubles ($651.8 billion) at Wednesday’s close to 53.02 trillion ($627.9 billion) by the end of trading Friday, according to exchange data.

The MOEX Russia Index, which tracks 43 of Russia’s largest publicly traded companies, lost 8.05% over the week — its worst performance since late September 2022, when markets were rattled by the Kremlin’s announcement of mass mobilization for the war in Ukraine.

At the end of trading on Friday, shares in some of the country’s largest firms had plunged: Sberbank fell by 5.2%, Gazprom 4.9%, VTB 6%, Rosneft 3.9% and Lukoil 4.6%. Mechel, the steel and coal giant, dropped more than 7%, while flagship airline Aeroflot slid 4.8% and gas producer Novatek fell 5.4%.

“A massive crisis is unfolding before our eyes,” said Yevgeny Kogan, an investment banker and professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow.

Here is the full story, via C. At least Trump does not seem to be a Russian agent…

Common sense from Ross Douthat

Now for my own view. I think trying to reshore some manufacturing and decouple more from China makes sense from a national security standpoint, even if it costs something to G.D.P. and the stock market. Using revenue from such a limited, China-focused tariff regime to pay down the deficit seems entirely reasonable.

I am more skeptical that such reshoring will alleviate specific male blue-collar social ills, because automation has changed the industries so much that I suspect you would need some sort of social restoration first to make the current millions of male work force dropouts more employable.

And I am extremely skeptical of any plan that treats pre-emptive global disruption as the key to avoiding a deficit crisis down the road. The “instigate a crisis now before our position weakens” has a poor track record in real wars — I don’t think trade wars are necessarily different.

Here is the full NYT piece. And from Armand Domalewski on Twitter: “there is no industry in America with stronger protectionism than the shipbuilding industry. The Jones Act makes it illegal to ship anything between two points in the US on a ship not built in the US and crewed by Americans. And yet America’s shipbuilding industry is nonexistent”