Results for “best book” 1836 found

The new Ben Horowitz management book

What You Do Is Who You Are: How to Create Your Own Business Culture. It is the best book on business culture in recent memory, here is one bit:

When Tom Coughlin coached the New York Giants, from 2004 to 2015, the media went crazy over a shocking rule he set: “If you are on time, you are late.” He started every meeting five minutes early and fined players one thousand dollars if they were late. I mean on time…”Players ought to be there on time, period,” he said. “If they’re on time, they’re on time. Meetings start five minutes early.”

And:

Two lessons for leaders jump out from Senghor’s experience:

-

Your own perspective on the culture is not that relevant. Your view or your executive team’s view of your culture is rarely what your employees experience.

You can pre-order the book here, due out in October.

Which are the best autobiographies by women?

That question has been floating around Twitter, here are my picks:

Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar.

Janet Frame, Autobiography.

Claire Tomalin, A Life of My Own.

Marjane Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis.

Golda Meir, My Life.

Joan Didion, The Year of Magical Thinking.

Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Dirt Road.

Temple Grandin, Thinking in Pictures.

Am I allowed to say Virginia Woolf, corpus?

Nadezhda Mandelstam, Hope Against Hope: A Memoir.

Helen Keller, The Story of My Life.

Anne Frank of course.

What else? Maybe Carrie Fisher? Maya Angelou? Erica Jong? St. Therese of Liseaux? (I Am Rigoberto Menchu turned out to be a fraud.) There are a variety of important feminist books that read like quasi-autobiographies, but maybe they don’t quite fit the category. What is a memoir and what is an autobiography in this context? Do leave your suggestions in the comments.

It is also worth thinking about how these differ from well-known male autobiographies…

Gustave Flaubert on travel books

Only, travel writing as a genre is per se almost impossible. To eliminate all repetitions you would have had to refrain from telling what you saw. This is not the case in books devoted to descriptions of discoveries, where the author’s personality is the focus of interest. But in the present instance the attentive reader may well find that there are too many ideas and insufficient facts, or too many facts and not enough ideas.

That is from his November 1866 letter to Hippolyte Taine, reproduced in the Francis Steegmuller collection. Here is my recent post on why most travel books are not good enough. Here is a 2006 MR post on which are the best travel books.

Mostly returned books

I have thought about this question for at least twenty years, Elisa Gabbert spells it out (NYT):

My favorite spot in my local library — the central branch in Denver — is not the nook for new releases; not the holds room, where one or two titles are usually waiting for me; not the little used-book shop, full of cheap classics for sale; and not the fiction stacks on the second floor, though I visit all those areas frequently. It’s a shelf near the Borrower Services desk bearing a laminated sign that reads RECENTLY RETURNED.

This shelf houses a smallish selection of maybe 40 to 60 books — about the number you might see on a table in the front of a bookstore, where the titles have earned a position of prominence by way of being new or important or best sellers or staff favorites. The books on the recently returned shelf, though, haven’t been recommended by anyone at all. They simply limit my choices by presenting a near-random cross section of all circulating parts of the library: art books and manga and knitting manuals next to self-help and philosophy and thrillers, the very popular mixed up with the very obscure. Looking at them is the readerly equivalent of gazing into the fridge, hungry but not sure what you’re hungry for.

Is it better to spend time, at the margin, pawing through the “recently returned” cart, or the “New Arrivals” section or for that matter just the regular shelves? How about the books simply left on tables and abandoned?

The big advantage of the books on the carts is that they usually are not bestsellers. For bestsellers there is a waiting list, and they are held for another patron, never making their way to the cart. I say go for the carts.

Best fiction of 2018

This year produced a strong set of top entries, though with little depth past these favorites. Note that sometimes my review lies behind the link:

Varlam Shalamov, Kolyma Stories.

Gaël Faye, Small Country. Think Burundi, spillover from genocide, descent into madness, and “the eyes of a child caught in the maelstrom of history.”

Madeline Miller, Circe.

Karl Ove Knausgaard, volume six, My Struggle. Or should it be listed in the non-fiction section?

Can Xue, Love in the New Millennium.

Anna Burns, Milkman, Booker Prize winner, Northern Ireland, troubles, here is a good and accurate review.

Homer’s Odyssey, translated by Emily Wilson.

Uwe Johnson, From a Year in the Life of Gessine Cresspahl. I haven’t read this one yet, I did some browse, and I am fairly confident it belongs on this list. 1760 pp.

Which are your picks?

Amazon search is getting worse, especially for classic books

Just type in “Gulliver’s Travels,” and the first page will not show any editions you actually ought to buy. And there are so many sponsored ads for mediocre, copyright-less editions. If you type in “Gulliver’s Travels Penguin” you eventually will get to this, a plausible buy for the casual educated reader. And wouldn’t it be nice if someone told you the $156.31 Cambridge University Press edition is by far the best choice? — full of marginal annotations!

The best job market paper I have seen so far this year

From Hyejun Kim at MIT”s Sloan School:

Knitting Community: Human and Social Capital in the Early Transition into Entrepreneurship

The process by which individuals become entrepreneurs is often described as a decisive moment of transition, yet it necessarily involves a series of smaller steps. This study examines how human capital and social capital are accumulated and deployed in the earliest stages of the entrepreneurial transition in the setting of “user entrepreneurship.” Using the unique dataset from Ravelry—the Facebook of knitters—I study why and how some knitters become entrepreneurs. I show that knitters who make the entrepreneurial transition are distinctive in that they have experience in fewer techniques and more product categories. I also show that this transition is facilitated by participation in offline social networks where knitters garner feedback and encouragement. Importantly, social and human capital appear to complement each other with social capital producing the greatest effect on the most skilled users. Broader theoretical implications on user innovation, the role of social capital, and entrepreneurship research are discussed.

Here is part of the concluding summary:

…the critical factor explaining why some creative knitters transition to designers is the feedback and encouragement they receive from fellow knitters and friends. With a carefully matched sample, difference-in-difference analysis verifies that the participation in an offline local networking group increases the likelihood of transition by 25%. Furthermore, the results suggest that social capital effect is largest among those with entrepreneurial human capital, as social capital complements human capital in knitters’ transition to

designers.

I have read through the entire paper and the whole thing is a gem.

Why you should hesitate to give books as gifts and instead just throw them out

I wrote this as a blog post for Penguin blog about ten years ago (when I guest-blogged for them), and it has disappeared from Google. So I thought I would serve up another, slightly different version to keep it circulating. Here goes:

Most of you should throw books out — your used copies that is — instead of gifting them. If you donate the otherwise-thrashed book somewhere, someone might read it. OK, maybe that person will read one more book in life but more likely that book will substitute for that person reading some other book instead. Or substitute for watching a wonderful movie.

So you have to ask yourself — this book — is it better on average than what an attracted reader might otherwise spend time with? Even within any particular point of view most books simply aren’t that good, and furthermore many books end up being wrong. These books are traps for the unwary, and furthermore gifting the book puts some sentimental value on it, thereby increasing the chance that it is read. Gift very selectively! And ponder the margin.

You should be most likely to give book gifts to people whose reading taste you don’t respect very much. That said, sometimes a very bad book can be useful because it might appeal to “bad” readers and lure them away from even worse books. Please make all the appropriate calculations.

Alternatively, if a rational friend of yours gives you a book, perhaps you should feel a little insulted.

How good is the very best next book that you haven’t read but maybe are on the verge of picking up? So many choices in life hinge on that neglected variable.

Toss it I say!

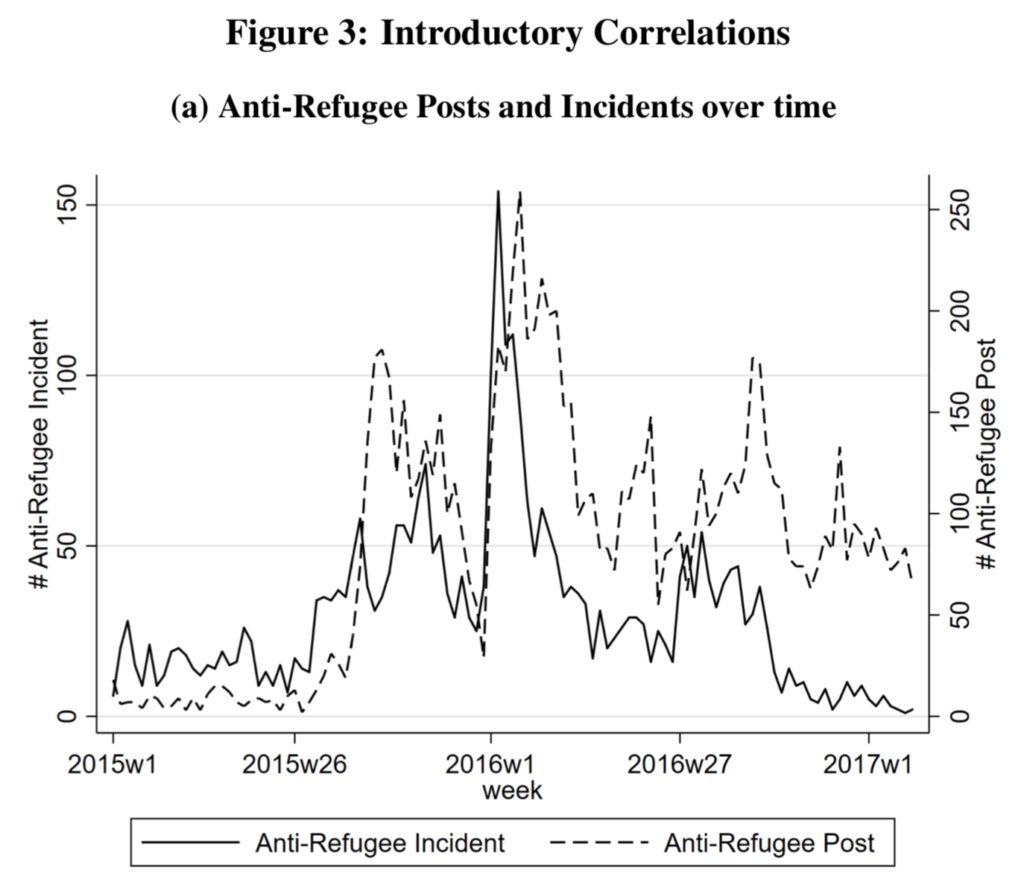

Is Facebook causing anti-refugee attacks in Germany?

Here is the key result, as summarized by the NYT:

Wherever per-person Facebook use rose to one standard deviation above the national average, attacks on refugees increased by about 50 percent.

Here is the underlying Müller and Schwarz paper. They consider 3,335 attacks over a two-year period in Germany. But I say no, their conclusion has not been demonstrated. Where to start?

Here is one picture showing a key correlation:

That looks pretty strong, doesn’t it? Nein! That is not how propaganda works, as an extensive literature in sociology and political psychology will indicate. That is how it looks when you measure what is essentially the same variable — or its effects — two different ways. For instance, that very big spike in the middle of the distribution? As Ben Thompson has pointed out, it represents the New Year’s harassment attacks in Cologne. Maybe that caused both Facebook activity and other attacks to spike at the same time? Will you mock me if I resort to the “blog comment cliche” that correlation does not show causation?

That looks pretty strong, doesn’t it? Nein! That is not how propaganda works, as an extensive literature in sociology and political psychology will indicate. That is how it looks when you measure what is essentially the same variable — or its effects — two different ways. For instance, that very big spike in the middle of the distribution? As Ben Thompson has pointed out, it represents the New Year’s harassment attacks in Cologne. Maybe that caused both Facebook activity and other attacks to spike at the same time? Will you mock me if I resort to the “blog comment cliche” that correlation does not show causation?

To continue with the excellent Ben Thompson (he is worth paying for!), the identification method used in the paper is suspect, and he focuses on this quotation from the authors:

In our setting, the share of a municipality’s population that use the AfD Facebook page is an intuitive proxy for right-wing social media use; however, it is also correlated with differences in a host of observable municipality characteristics — most importantly the prevalence of right-wing ideology. We thus attempt to isolate the local component of social media usage that is uncorrelated with right-wing ideology by drawing on the number of users on the “Nutella Germany” page. With over 32 million likes, Nutella has one of the most popular Facebook pages in Germany and therefore provides a measure of general Facebook media use at the municipality level. While municipalities with high Nutella usage are more exposed to social media, they are not more likely to harbor right-wing attitudes.

The whole result rests on assumptions about Nutella? What if you used likes for Zwetschgenkuchen? Has a robustness test been done? Was a simple correlation not good or not illustrative enough? I’ll stick with the simple hypothesis that some municipalities have both more Facebook usage, due to high AfD membership, and also more attacks on refugees, and furthermore both of those variables rise in tense times. AfD is the German party with the strongest presence on Facebook, I am sorry to say.

You will note by the way that within Germany the Nutella page has only verifiable 21,915 individual interactions, including likes (32 million is the global number of Nutella likes…die Deutschen are not that nutty), and that is distributed across 4,466 municipal areas. (If you are confused, see p.12 in the paper, which I find difficult to follow and I suspect that represents the confusion of the authors.) That should make you more worried yet about the Nutella identification strategy. They never tell us what they would have without Nutella, a better tasting sandwich I would say.

I also would note the broader literature on propaganda once again. Consider the research of Markus Prior: “…evidence for a causal link between more partisan messages and changing attitudes or behaviors is mixed at best.” These Facebook results are simply far outside of what we normally suppose to be true about human responsiveness — so maybe the company is undercharging for its ads!

Ben adds:

I am bothered by the paper’s robustness section in two ways: first, every single robustness test confirmed the results. To me that does not suggest that the initial result must be correct; it suggests that the researchers didn’t push their data hard enough. There is always a test that fails, and that is a good thing: it shows the boundaries of what you have learned. Second, there were no robustness tests applied to one of the more compelling pieces of evidence, that Internet and Facebook outages were correlated with a reduction in violence against refugees. This is particularly unfortunate because in some ways this evidence works against the filter bubble narrative: after all, the idea is the filter bubbles change your reality over time, not that they suddenly inspire you to action out of the blue.

The authors do present natural experiments from Facebook and internet outages. They find that “…for a given level of anti-refugee sentiment, there are fewer attacks in municipalities with high Facebook usage during an internet outage than in municipalities with low Facebook usage without an outage.” (p.28). Again I find that confusing, but I note also that “internet outages themselves…do not have a consistent negative effect on the number of anti-refugee sentiments.” That is the simple story, and it appears to exonerate Facebook. pp.28-30 then present a number of interaction effects and variable multiplications, but I am not sure what to conclude from the whole mess. I’m still expecting internet outages to lower the number of attacks, but they don’t.

Even if internet or Facebook outages do have a predictive effect on attacks in some manner, it likely shows that Facebook is a communications medium used to organize gatherings and attacks (as the telephone once might have been), not, as the authors repeatedly suggest, that Facebook is somehow generating and whipping up and controlling racist sentiment over time. Again, compare such a possibility to the broader literature. There is good evidence that anti-semitic violence across German regions is fairly persistent, with pogroms during the Black Death predicting synagogue attacks during the Nazi time. And we are supposed to believe that racist feelings dwindle into passivity simply because the thugs cannot access Facebook for a few days or maybe a week? By the way, in their approach if there is an internet outrage, mobile devices do not in Germany pick up the slack.

I’d also like to revisit the NYT sentence, cited above, and repeated many times on Twitter:

Wherever per-person Facebook use rose to one standard deviation above the national average, attacks on refugees increased by about 50 percent.

That sounds horrible, but it is actually a claim about variation across municipalities, not a claim about the absolute importance of the internet. The authors also reported a very different and perhaps more relevant claim to the Times:

…this effect drove one-tenth of all anti-refugee violence.

I would have started the paper with that sentence, and then tried to estimate its robustness, without relying on Nutella.

As it stands right now, you shouldn’t be latching on to the reported results from this paper.

What are the best analyses of small, innovative, productive groups?

Shane emails me:

Hello!

What have you found to be the best books on small, innovative, productive groups?

These could be in-depth looks at specific groups – such as The Idea Factory, about Bell Labs – or they could be larger studies of institutions, guilds, etc.

I suggest reading about musical groups and sports teams and revolutions in the visual arts, as I have mentioned before, taking care you are familiar with and indeed care passionately about the underlying area in question. Navy Seals are another possible option for a topic area. In sociology there is network theory, but…I don’t know. In any case, the key is to pick an area you care about, and read in clusters, rather than hoping to find “the very best book.” The very theory of small groups predicts this is how you should read about small groups!

But if you must start somewhere, Randall Collins’s The Sociology of Philosophies is probably the most intensive and detailed place to start, too much for some in fact and arguably the book strains too hard at its target.

I have a few observations on what I call “small group theory”:

1. If you are seeking to understand a person you meet, or might be hiring, ask what was the dominant small group that shaped the thinking and ideas of that person, typically (but not always) at a young age. Step #1 is often “what kind of regional thinker is he/she?” and step #2 is this.

2. If you are seeking to foment change, take care to bring together people who have a relatively good chance of forming a small group together. Perhaps small groups of this kind are the fundamental units of social change, noting that often the small groups will be found within larger organizations. The returns to “person A meeting person B” arguably are underrated, and perhaps more philanthropy should be aimed toward this end.

3. Small groups (potentially) have the speed and power to learn from members and to iterate quickly and improve their ideas and base all of those processes upon trust. These groups also have low overhead and low communications overhead. Small groups also insulate their members sufficiently from a possibly stifling mainstream consensus, while the multiplicity of group members simultaneously boosts the chances of drawing in potential ideas and corrections from the broader social milieu.

4. The bizarre and the offensive have a chance to flourish in small groups. In a sense, the logic behind an “in joke” resembles the logic behind social change through small groups. The “in joke” creates something new, and the small group can create something additionally new and in a broader and socially more significant context, but based on the same logic as what is standing behind the in joke.

5. How large is a small group anyway? (How many people can “get” an inside joke?) Has the internet made “small groups” larger? Or possibly smaller? (If there are more common memes shared by a few thousand people, perhaps the small group needs to be organized around something truly exclusive and thus somewhat narrower than in times past?)

6. Can a spousal or spouse-like couple be such a small group? A family (Bach, Euler)?

7. What are the negative social externalities of such small groups, compared to alternative ways of generating and evaluating ideas? And how often in life should you attempt to switch your small groups?

8. What else should we be asking about small groups and the small groups theory of social change?

9. What does your small group have to say about this?

I thank an anonymous correspondent — who adheres to the small group theory — for contributions to this post.

Where do our best ideas come from?

A correspondent writes to me:

Isn’t it weird that the best ideas we have just…. pop into your head? I have no idea how to trace them. They just show up.

@Tyler any research into this area?

Dean Keith Simonton springs readily to mind, noting he has a new book coming out this year on genius. Here are some overview pieces on simultaneous discovery, and of course those tend to stress environmental factors. Here are some approaches to the multiplicative model of creative achievement. I am a fan of that one. What else?

Why Did Trump Pay Less than Clinton For Ads on Facebook?

An article in Wired has sparked controversy with its claim that Trump paid lower prices for its Facebook ads than Clinton:

During the run-up to the election, the Trump and Clinton campaigns bid ruthlessly for the same online real estate in front of the same swing-state voters. But because Trump used provocative content to stoke social media buzz, and he was better able to drive likes, comments, and shares than Clinton, his bids received a boost from Facebook’s click model, effectively winning him more media for less money. In essence, Clinton was paying Manhattan prices for the square footage on your smartphone’s screen, while Trump was paying Detroit prices.

The claim is plausible but although written by a Facebook expert it never really explains why Google and Facebook prices their ads in this way. The reason is what I call the “mesothelioma lawyer” problem. A click on an ad for a “mesothelioma lawyer” is extremely valuable because people who aren’t interested in hiring a mesothelioma lawyer are unlikely to click and those who do click are likely to become profitable clients. Thus, anyone searching for mesothelioma is likely to see an ad for a mesothelioma lawyer.

But suppose that Google or Facebook simply charge for ads by the click. Someone who searches for “funny hat video” isn’t likely to click on an ad for a mesothelioma lawyer but the people who do click are still likely to be very profitable to a mesothelioma lawyer. As a result, the mesothelioma lawyer can outbid the seller of funny hats for ads connected to “funny hat video” even though the search has nothing to do with mesothelioma. If Google or Facebook only charged by the click it would be mesothelioma lawyer ads everywhere, all the time.

To avoid this problem, Google and Facebook calculate how many clicks or interactions your ad is likely to receive and they charge lower prices the greater the predicted number of clicks. As a result, sellers of funny hats get lower prices than mesothelioma lawyers for ads that pop up after the user watches a funny hat video and mesothelioma lawyers get lower prices than sellers of funny hats for ads that pop up after the user searches for information on mesothelioma. In the long run this system better targets ads to customers and thus maximizes the value of the platform to both advertisers and customers.

As the Wired piece eventually states this isn’t even new:

“I always wonder why people in politics act like this stuff is so mystical,” Brad Parscale, the leader of the Trump data effort, told reporters in late 2016. “It’s the same shit we use in commercial, just has fancier names.”

He’s absolutely right. None of this is even novel: It’s merely best practice for any smart Facebook advertiser.

Addendum: See also Hal Varian’s discussion of the underlying issues in the Online Advertising section of this paper.

Books that had hidden influence on me

Way back when, I considered the ten books that influenced me most, a list I still stand by. In response, someone asked me to name the books that influenced me, but whose influence I probably was not aware of. Let’s ignore the semi-contradiction in that request and plow straight ahead! Here goes, noting that if memory serves I read most of these between the ages of 10 to 12:

1. Alexander Kotov, Think Like a Grandmaster. From this book I realized you could think you understood a chess position, but then later learn you didn’t really understand it at all. A huge lesson, one I learned again and to a higher degree when high-quality chess computers came along. Most of the commentariat on economic and social affairs could use a reminder on this one. This book also taught me that you learn by doing — trying to solve actual problems — not so much from pure reading. Or the two in close conjunction. It may be the distortions of memory, but still I feel this is one of the best books I ever have read. Hail the Soviet training system!

2. Bobby Fischer, My Sixty Memorable Games of Chess. Reflects a certain kind of classicism in thinking and method. Later, it was revealed much of the analysis was faulty and in part was from Larry Evans and not Fischer himself.

3. Reuben Fine, Basic Chess Endings. I wasn’t influenced so much by this book itself as by a long series of articles in Chess Life and Review, showing the analysis was full of holes. See my remarks on Kotov.

4. David Kahn, The Code-Breakers, The Story of Secret Writing. I read this one quite young, and learned that problems are to be solved! I also developed some sense of what a history could look like and what a history should report. I recall my uncle thinking it deeply strange that a boy my age should be reading a book of such length.

5. Rudolf McShane and Jakow Trachtenberg, The Trachtenberg System of Basic Mathematics. From this I learned how powerful the individual human mind could be, and also how much school wasn’t teaching me. It began to occur to me that the mainstream doesn’t necessarily have the best or only methods. That said, non-mainstream approaches still have the responsibility of coming up with the right answer. Query: does it these days ever make sense to actually use this stuff?

6. The Baseball Encyclopedia, or something like that. From this book I began to figure out statistics and how they fit into broader patterns of historical explanation. I spent a lot of time with this one even before the age of ten. It helped me understand my baseball cards in terms of a much longer perspective and also, if I recall correctly, it explained the underlying meaning of many of the statistics, albeit in what would today count as a very naive, non-Moneyball manner. I still know that Chief Wilson hit 36 triples in 1912.

Honorable mentions: Jonathan Livingston Seagull, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, and The Joy of Sex, all given to me by my mother. I believe they helped inculcate some of the 1960s-70s ethos of individual freedom into my thinking. I also consumed numerous sports memoirs, such as Jerry Kramer’s Instant Replay: The Green Bay Diary of Jerry Kramer and also the war memoir Guadalcanal Diary. From those I began to think about the relationships between character, work habits, teamwork, and success. The Making of Star Trek helped me master the details of what was then my favorite TV series, and also to think about cosmopolitanism across different kinds of intelligent beings. In addition to chess I also was influenced by playing paper and dice war games, most of all Barbossa (the exact title may differ slightly), a really scary game where you have to consider the possibility the Nazis could have won and thus think about the contingency of history. I began to understand that violence could be a reality that stood above all else and how important it was to avoid such a scenario.

Then there is youthful science fiction, though perhaps that someday gets a post of its own. I read a lot of books about music too, many about jazz solos and chord composition, including in American popular music. Much earlier, maybe ages 5-8, it was maps and books full of facts about the world (ahem) and animals, most of all the taxonomic arrangement of the animal kingdom.

Finally, at the time I was fully aware that I wasn’t getting a single one of these titles through my formal school system.

My visit to an Amazon bookstore

My commentary here is late to the party, but I had not visited a branch before. Here are my impressions, derived from the Columbus Circle outlet in Manhattan:

1. It is a poorly designed store for me, most of all because it does not emphasize new releases. I feel I am familiar with a lot of older titles, or I went through a more or less rational process of deciding not to become familiar with them. Their current popularity, as measured say by Amazon rankings, does not cause me to reassess those judgments. For me, aggregate Amazon popularity has no real predictive power, except perhaps I don’t want to buy books everyone liked. “A really smart person says to consider this again,” however, would revise my prior estimates.

2. For me, the very best bookstore and bookstore layout is Daunt, in London, Marylebone High St. You are hit by a blast of what is new, but also selected according to intellectual seriousness rather than popularity. You can view many titles at the same time, because they use the “facing out” function just right for their new arrivals tables. Some of the rest of the store is arranged “by country,” much preferable to having say China books in separate sections of history, travel, biography, and so on.

3. I am pleased that fiction is given so much space toward the front of the store. I do not see this as good for me, but it is a worthwhile counterweight to the ongoing tendency of American book markets to reward non-fiction, or at least what is supposed to be non-fiction.

4. I have mixed feelings about the idea of all books facing outward. On the positive side, books not facing outward tend to be ignored. On the downside, this also limits the potential for hierarchicalization through visual display. All books facing outwards is perhaps a bit too much like no books facing outwards.

Overall I am struck by how internet commerce is affecting Christie’s and Sotheby’s in a broadly similar fashion. The auction houses used to put out different genres, such as Contemporary, European Painting, 20th Century, and so on, for 3-4 day windows, and then they would display virtually everything up for auction. Now they have a single big display, with highlights from each area, and the rest viewable on-line. That display then shows for about three weeks. Like Amazon, they are opting to emphasize what is popular and to let on-line displays pick up the tails and niches. In all cases, that means less turnover in the displays. That is information-rich for infrequent visitors, who can take in more at once, but information-poor in relative terms for frequent visitors. As a somewhat infrequent visitor to auction houses, I gain, but for bookstores I would prefer they cater to the relatively frequent patrons.

5. I am most worried by the prominent center table at the entrance, which presents “Books with 4.8 Amazon stars or higher.” I saw a book on mixology, a picture book of Los Angeles, a Marvel comics encyclopedia, a book connected to the musical Hamilton, and a series of technique-oriented cookbooks, such as Harold McGee, a very good manual by the way. Isabel Wilkerson was the closest they had to “my kind of intelligent non-fiction.” Neil Hilbon represented poetry, of course his best-known book does have a five-star average, fortunately “…these poems are anything but saccharine.”

Unfortunately, the final message is that Amazon will work hard so that controversial books do not receive Amazon’s highest in-store promotions. Why not use software to measure the quality of writing or maybe even thought in a book’s reviews, and thereby assign it a new grade?: “Here are the books the smart people chose to write about”?

6. I consider myself quite pro-Amazon, still to me it feels dystopic when an attractive young saleswoman says so cheerily to (some) customers: “Thank you for being Prime!”

7. I suspect the entire store is a front to display and sell gadgets, at least I hope it is.

8. I didn’t buy anything.

The one hundred best solutions to global warming?

Jason Kottke reports:

On the website for the book, you can browse the solutions in a ranked list. Here are the 10 best solutions (with the total atmospheric reduction in CO2-equivalent emissions in gigatons in parentheses):

1. Refrigerant Management (89.74)

2. Wind Turbines, Onshore (84.60)

3. Reduced Food Waste (70.53)

4. Plant-Rich Diet (66.11)

5. Tropical Forests (61.23)

6. Educating Girls (59.60)

7. Family Planning (59.60)

8. Solar Farms (36.90)

9. Silvopasture (31.19)

10. Rooftop Solar (24.60)Refrigerant management is about replacing hydro-fluorocarbon coolants with alternatives because HFCs have “1,000 to 9,000 times greater capacity to warm the atmosphere than carbon dioxide”. As a planet, we should be hitting those top 7 solutions hard, particularly when it comes to food. If you look at the top 30 items on the list, 40% of them are related to food.

Here is the background context:

Environmentalist and entrepreneur Paul Hawken has edited a book called Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming which lists “the 100 most substantive solutions to reverse global warming, based on meticulous research by leading scientists and policymakers around the world”.

I will however order the book.