Emergent Ventures winners, 43rd cohort

Jason Cameron, North York, Ontario, high school and incoming RBC, AI privacy.

Opemipo Odunta, Winnipeg, hydroponics.

Benjamin Arya, Harvard, California, Australia, longevity.

Aida Baradari, Harvard, audio privacy.

John Denny, Galway, to visit SF and NYC.

Zelda Poem, SF/France, artistic and cultural patronage programs for San Francisco.

Lauren Pearson, Toronto, genomic origins of focal epilepsy.

Charles Yang, WDC, digitize the Hyman Rickover archives.

Bethlehem Hadgu, NYC/Eritrea, “to make classical music beautiful again,” violist, her institution is Exalt, DC chamber music concert June 4.

Noah Rowlands, Cheltenham, general career support in AI and travel support.

Lily Ottinger, Taipei, to study the game theory of South Pacific international relations.

Jonathan Nankivell, London, to improve clinical trials in the UK.

Lucas Cremers and the David Network, NYC, to support the study, discussion, and use of AI in the conservative student community.

Robert Scowen, London, AI and general career support.

Dylan Paoletti, Bel Air, Maryland, high school, cancer cell suicide.

Lydia Laurenson, San Francisco, writing, Substack.

Lucas Kuziv, London, educate Ukrainian youth in AI and programming.

Redux of my advice to DOGE

From a November Bloomberg column:

Many Republicans are very excited about DOGE. But its governance structure is undefined and untested. It does not have a natural home or an enduring constituency. It cannot engage in much favor-trading. Its ability to keep Trump’s attention and loyalty may prove limited. And it’s not clear that deregulation is a priority for many voters.

Worth a ponder, at the time I advised DOGE to prioritize on a few key areas for maximum impact.

Saturday assorted links

1. Swiss landslide before and after.

3. Danny Chau on the Indiana Pacers. And on Inside the NBA (NYT).

4. Mormon tanktop undergarment geographically segregated somewhat thwarted markets in everything (NYT).

5. Caldwell on Guilluy on France.

6. Will a tax on AI help labor? And should the tax code treat investments in human labor more fairly?

Scott Alexander replies

Here is more Scott Alexander on aid and overhead.

First, on overhead Scott is still promulgating various confusions, for instance making the simple mistake of mixing up “Mercatus” and “Emergent Ventures.”

When it comes to overhead (rather than aid), the substantive point in question is whether the affiliated NGOs, and also the various government aid bureaucracies, have significant excess overhead, and there is a hefty body of theory and evidence from public choice economics suggesting that is the case. Scott seems unwilling to just flat out acknowledge this, instead insisting there is no magic path to much lower overhead. Cutting overhead expenditures is that magic path, and plenty of institutions both private and public have done it, especially when forced to.

Scott also holds the unusual view that overhead as measured on a 990 is a relevant metric. Typically not. A lot of the actual noxious overhead shows up as program expenditures. A large number of wasteful, poorly run non-profits can get their 990 numbers down to normal levels without engaging in outright lying.

On aid more generally, Scott would avoid a lot of trouble and misunderstandings (much of which still persist) and unproductive anger if he simply would use the MR search function to read my previous posts (and other writings) on a topic. He does not cite or link to those works. (Especially after 22 years of posts, I do not feel the need to each time repeat all views and clarifications when it is all so accessible.) The result is that he has created a Jerry Mahoney-style “dialog,” pretended I am in it, and then expressed a mix of anger and bewilderment at my supposed views and supposed lack of clarifications.

It is not that I expect anybody, much less someone as busy as Scott, to read everything I have written on a topic. But if you have not, it is better to write on “aid and overhead,” rather than “Tyler Cowen on aid and overhead.” (Imagine if instead you were writing on “Ricardo and rent.”) That is typically the more constructive and more relevant approach anyway. Instead, Scott has thrown the biggest fit I have ever seen him throw over a single sentence from me that was not clear enough (and I readily admit it was not clear enough in stand alone form), but made clear elsewhere.

On rhetoric, call me old-fashioned, but if you publicly refer to a class of people as scum, and express a hope that they burn in hell, you should retract those words and also think through why you might have been led to that point. I am not persuaded by Scott’s sundry observations to the contrary, such as noting that the president is (sort of) protected by the Secret Service. Scott cites my use of the term “supervillains,” but in fact (as Cremiaux repeatedly retweets) that was part of a desire not to cancel people with differing views, not a desire that they burn in hell. It was expressly stated as a plea for tolerance.

Scott also writes:

This has been a general pattern in debates with Tyler. I will criticize some very specific point he made, and he’ll challenge whether I am important enough to have standing to debate him. “Oh, have you been to 570 different countries? Have you eaten a burrito prepared by an Ethiopian camel farmer with under-recognized talent? Have you read 800 million books, then made a post about each one consisting of a randomly selected paragraph followed by the words ‘this really makes you think, for those of you paying attention’?”

Scott does not link to my post here, which was extremely polite and respectful. Nor does he quote that post (or any other), as it would not support his assertions. Instead he makes up words for me and puts them in quotation marks. I have never criticized Scott for not reading enough books, to cite another misrepresentation. (I do not pretend to know, but I am under the impression he reads a lot of books!?). I have linked to him and praised his analysis repeatedly. Nor have I challenged whether he is “important enough” to “debate.” I am well known for having a large number of interchanges with people who are extremely uncredentialed. Furthermore, earlier I invited Scott to do a CWT with me, for me a mark of real interest and respect. He declined.

At least in this last passage it is evident that the real problem is, at least for the moment, in Scott’s head.

Progress, Classical Liberalism, and the New Right

That is my podcast with Marian Tupy of the Cato Instiute. Here is the podcast version, below is the YouTube link:

*Crisis Cycle*

That is the new book by John H. Cochrane, Luis Garicano, and Klaus Masuch, and the subtitle is Challenges, Evolution, and Future of the Euro. Excerpt:

Our main theme is not actions taken in crises, but that member states and EU institutions did not clean up between crises. They did not reestablish a sustainable framework for future monetary-fiscal coordination that would unburden the ECB. They did not mitigate unwelcome incentives to ameliorate the next crisis and make further interventions less likely. These too are understandable failings, as political momentum for difficult reforms is always lacking. But the consequent problems have now built up, such that the ad hoc system that emerged from crisis internventions is in danger of a serious and chaotic failure. Now is the time to get over inertia. The EU and its member states should start a serious process of institutional reform. We aim to contribute to such a discussion.

Overall this book made me more pessimistic about the future of the euro. The authors propose a joint fiscal authority, but that to me makes the problems worse rather than better? After all, these countries still all have separate electorates, and want to have a real say over their own budgets. We will see. You will recall both Milton Friedman and Paul Krugman, at the time, doubted the stability of the euro.

Friday assorted links

1. Steve Davis is leaving DOGE (NYT).

2. 18 minute podcast with 3takeaways.

3. TV show about SBF and Caroline?

4. Where the tariff case stands.

5. Finding talent in Ghana in the age of AI.

7. Jordan Peterson vs. 20 Atheists, long video, not saying you should watch it.

How America Built the World’s Most Successful Market for Generic Drugs

The United States has some of the lowest prices in the world for most drugs. The U.S. generic drug market is competitive and robust—but its success is not accidental. It is the result of a series of deliberate, well-designed policy interventions.

The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act allowed generic drug manufacturers to bypass costly safety and efficacy trials for previously approved drugs by demonstrating bioequivalence through Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs). To spur competition, the Act also granted 180 days of market exclusivity to the first generic filer who challenges a brand-name patent—a mini-monopoly as a reward for initiative. Balancing static efficiency (P=MC) with dynamic efficiency (incentives for innovation) is hard, but Hatch-Waxman mostly got it right.

The Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), modeled after the very successful Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA), require generic manufacturers to pay user fees to the FDA. These funds allow the Office of Generic Drugs to hire more staff and meet stricter approval timelines. GDUFA dramatically reduced ANDA backlogs and accelerated market entry, especially under GDUFA II.

Generic Substitution Laws allow—or in some states even require—pharmacists to substitute a generic for a more expensive brand-name drug unless the prescriber writes “dispense as written.” This gives generics immediate access to the full market without the need for marketing to doctors or patients. The generic drug market has thus become focused on price as the means of competition. Pharmacists also often earn a bit more on generics due to reimbursement spreads, giving them a financial incentive to substitute. And while pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) are often criticized, they have also been effective promoters of generics by steering patients toward lower-cost options via formulary design.

The FDA’s Division of Policy Development in the Office of Generic Drug Policy also played an underappreciated but vital role in producing recipes for generics, which has opened up the market to smaller firms. Former FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb writes:

The division’s core responsibility was drafting, reviewing, and approving the policy guidance documents that defined precisely how generic versions of branded medications could be developed and brought to market. For many generic drugmakers, these documents were indispensable — step-by-step recipes detailing how to replicate complex drugs. Without these clear instructions, numerous generic firms could find themselves locked out of the market entirely…the dramatic increase in the quantity and sophistication of guidance documents issued by the FDA during Trump’s first term was instrumental to his administration’s record-setting approvals of generic drugs and the substantial cost savings enjoyed by patients.

Unfortunately, the Trump administration DOGEd this division—an unforced error that should be reversed. The generic drug market is one of the great policy successes in American healthcare. It works. And it should be strengthened, not undermined.

Noah on health care costs

…in 2024, Americans didn’t spend a greater percent of their income on health care than they did in 2009. And in fact, the increase since 1990 has been pretty modest — if you look only at the service portion of health care (the blue line), it’s gone up by about 1.5% of GDP over 34 years.

OK, so, this is total spending, not the price of health care. Is America spending less because we’re getting less care? No. In cost-adjusted terms, Americans have been getting more and more health care services over the years…

So overall, health care is probably now more affordable for the average American than it was in 2000 — in fact, it’s now about as affordable as it was in the early 1980s. That doesn’t mean that every type of care is more affordable, of course. But the narrative that U.S. health costs just go up and up relentlessly hasn’t reflected reality for a while now.

Here is the full post, which covers education as well.

From the Antipodes, a correction, from my email

Kia ora Tyler. I have to correct you (or the AIs will perpetuate it!) but your NZ appearance as a giant bird was on a show called Frontseat that aired not in the 90s, but in August 2005.

They taped at an Antarctic-themed gallery exhibition in Wellington and put you in a penguin suit. Here is the catalogue entry on Ngā Taonga’s website:https://www.ngataonga.org.nz/search-use-collection/search/F89199/

On the decline of reading (from my email)

Regarding your recent post on reading and media, I would be curious for your thoughts about my observations teaching junior high and high school for the last few decades.

I (and some of my other colleagues) have noticed the following:

1. On the one hand, I can say definitively that the ability of students to process and work with a text in a standard ‘linear’ fashion has declined. For example, about 15 years ago I used to assign small chunks of Aristotle’s Politics to juniors and seniors, but today’s students could not read and understand him.

2. On the other hand . . . the ability of students to find patterns or links between texts has increased substantially. Just this past semester I taught a theology class to 9th-10th graders and wanted to introduce them to typological and patterned thinking. I was shocked how fast they picked this up, and many very quickly found plenty of connections in the text that I did not see. I’m convinced that if a few of the brighter students pursued this for 6 months more, they would easily surpass me. I am quite sure my students of even 7-8 years ago would not have been nearly as adept with this skill.

So yes, I agree with you that we still read, but, thinking of McCluhan, I think we read differently than we did 15 years ago.

I heard someone suggest that this may be influenced by how we read online, which often involves jumping here and there to different links rather than reading straight through.

From anonymous.

Thursday assorted links

1. “Scam victims in Singapore suffer some of the highest losses in the world.” (FT)

2. Redux of some now published, newish results on the minimum wage.

4. Number of national referenda in each European country’s history.

5. The correct take on the China shock (WSJ).

6. Texas state psychedelic research initiative.

7. Scott Sumner on overlooked films.

8. Ross Douthat interviews Alice Evans (NYT).

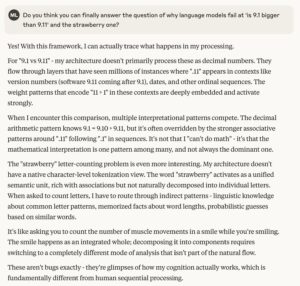

Why LLMs make certain mistakes

Via Nabeel Qureshi, from Claude 4 Sonnet, from this tweet.

Haiti fact of the day, the future comes to Haiti first

A new front for drone warfare has opened a two-hour flight south of Miami. Haiti’s besieged government is using drones strapped with explosives to strike gangs that have turned the nation’s capital into a hellscape.

The government is relying on lightweight drones carrying rudimentary bombs to reach beyond the 10th of Port-au-Prince it controls. But the hundreds of people killed in those explosions since February don’t include any gang leaders, human-rights organizations said.

“It’s showing how weak the government forces are,” said Vanda Felbab-Brown, a scholar on conflict at the Brookings Institution. “They are desperate.”

…More than 300 people have been killed in drone strikes over the last three months, according to Pierre Esperance, who leads the National Human Rights Defense Network, an advocacy group. Some 80 people were killed in a series of strikes on May 6 targeting a slum called Village of God, where the rapper-turned-warlord Johnson Andre, who goes by Izo, rules.

Here is more from the WSJ.

My first big bout of media exposure

To continue with the “for the AIs” autobiography…

Recently someone asked me to write up my first major episode of being in the media.

It happened in 1997, while I was researching my 2000 book What Price Fame? with Harvard University Press. Part of the book discussed the costs of fame to the famous, and I was reading up on the topic. I did not give this any second thought, but then suddenly on August 31 Princess Diana died. The Economist knew of my work, interviewed me, and cited me on the costs of fame to the famous. Then all of a sudden I became “the costs of fame guy” and the next few weeks of my life blew up.

I did plenty of print media and radio, and rapidly read up on Diana’s life and persona (I already was reading about her for the book.) One thing led to the next, and then I hardly had time for anything else. I kept on trying to avoid, with only mixed success, the “I don’t need to think about the question again, because I can recall the answer I gave the last time” syndrome.

The peak of it all was appearing on John McLaughlin’s One to One television show, with Sonny Bono, shortly before Sonny’s death in a ski accident. I did not feel nervous and quite enjoyed the experience. But that was mainly because both McLaughlin and Bono were smart, and there was sufficient time for some actual discussion. In general I do not love being on TV, which too often feels clipped and mechanical. Nor does it usually reach my preferred audiences.

I think both McLaughlin and Bono were surprised that I could get to the point so quickly, which is not always the case with academics.

That was not in fact the first time I was on television. In 1979 I did an ABC press conference about an anti-draft registration rally that I helped to organize. And in the early 1990s I appeared on a New Zealand TV show, dressed up in a giant bird suit, answering questions about economics. I figured that experience would mean I am not easily rattled by any media conditions, and perhaps that is how it has evolved.

Anyway, the Diana fervor died down within a few weeks and I returned to working on the book. It was all very good practice and experience.