Results for “age of em” 16700 found

Is Portugal an anti-austerity story?

A recent NYT story by Liz Alderman says yes, but I find the argument hard to swallow. Here’s from the OECD:

The cyclically adjusted deficit has decreased considerably, moving from 8.7% of potential GDP to 1.9% in 2013 and to 0.9% in 2014. This is better (lower) than the OECD average in 2014 (3.1%), reflecting some improvement in the underlying fiscal position of Portugal.

Or see p.20 here (pdf), which shows a rapidly diminishing Portuguese cyclically adjusted deficit since 2010. Now I am myself skeptical of cyclically adjusted deficit measures, because they beg the question as to which changes are cyclical vs. structural. You might instead try the EC:

…the lower-than-expected headline deficit in 2016 was mainly due to containment of current expenditure (0.8 % of GDP), particularly for intermediate consumption, and underexecution of capital expenditure (0.4% of GDP) which more than compensated a revenue shortfall of 1.0% of GDP (0.3% of GDP in tax revenue and 0.7% of GDP in non-tax revenue)

Does that sound like spending your way out of a recession? Too right wing a source for you? Catarina Principle in Jacobin wrote:

…while Portugal is known for having a left-wing government, it is not meaningfully an “anti-austerity” administration. A rhetoric of limiting poverty has come to replace any call to resist the austerity policies being imposed at the European level. Portugal is thus less a test case for a new left politics than a demonstration of the limits of government action in breaking through the austerity consensus.

Or consider the NYT article itself:

The government raised public sector salaries, the minimum wage and pensions and even restored the amount of vacation days to prebailout levels over objections from creditors like Germany and the International Monetary Fund. Incentives to stimulate business included development subsidies, tax credits and funding for small and midsize companies. Mr. Costa made up for the givebacks with cuts in infrastructure and other spending, whittling the annual budget deficit to less than 1 percent of its gross domestic product, compared with 4.4 percent when he took office. The government is on track to achieve a surplus by 2020, a year ahead of schedule, ending a quarter-century of deficits.

This passage also did not completely sway me:

“The actual stimulus spending was very small,” said João Borges de Assunção, a professor at the Católica Lisbon School of Business and Economics. “But the country’s mind-set became completely different, and from an economic perspective, that’s more impactful than the actual change in policy.”

Does that merit the headline “Portugal Dared to Cast Aside Austerity”? Or the tweets I have been seeing in my feed, none of which by the way are calling for better numbers in this article?

I would say that further argumentation needs to be made. Do note that much of the article is very good, claiming that positive real shocks help bring recessions to an end. For instance, Portuguese exports and tourism have boomed, as noted, and they use drones to spray their crops, boosting yields. That said, it is not just the headline that is at fault, as the article a few times picks up on the anti-austerity framing.

I’m going to call “mood affiliation” on this one, at least as much from the headline and commentary surrounding the article as the author herself.

Monday assorted links

Housing Costs Reduce the Return to Education

In normal times and places house prices are kept fairly close to construction costs by the ordinary processes of supply and demand. Average house prices didn’t rise much over the entire 20th century, for example. Even today, house prices are kept close to construction costs in most of the United States. But extreme supply restrictions in a small number of important places (San Francisco, San Jose, LA, New York, Boston etc.), have driven average prices well above any seen in the entire 20th century.

Over the last several decades high productivity industries have become more geographically concentrated. As a result, a substantial share of the productivity gains from technology, bio-tech and finance have gone not to producers but to non-productive landowners. High returns to land have meant lower returns to other factors of production.

The return to education, for example, has increased in the United States but it’s less well appreciated that in order to earn high wages college educated workers must increasingly live in expensive cities. One consequence is that the net college wage premium is not as large as it appears and inequality has been over-estimated. Remarkably Enrico Moretti (2013) estimates that 25% of the increase in the college wage premium between 1980 and 2000 was absorbed by higher housing costs. Moreover, since the big increases in housing costs have come after 2000, it’s very likely that an even larger share of the college wage premium today is being eaten by housing. High housing costs don’t simply redistribute wealth from workers to landowners. High housing costs reduce the return to education reducing the incentive to invest in education. Thus higher housing costs have reduced human capital and the number of skilled workers with potentially significant effects on growth.

Housing is eating the world.

Guyana estimate of the day

The Guyanese government, under its agreement with Exxon, will receive roughly half the cash flow from oil production once the company’s costs are repaid. Economists say that will mean the country’s current gross domestic product of $3.6 billion will at least triple in five years.

That is from a longer feature article by Clifford Krauss at the NYT.

Facts about abortion history

1. In 1800, there were no formal laws against abortion in the United States, although common law suggested that the fetus had rights after a process of “quickening.”

2. Ten states passed anti-abortion laws in the 1821-1841 period. De facto there were many exceptions and enforcement was loose.

3. Abortion became a fully commercialized business in the 1840s, and this led to more public discussion of the practice. Abortion in fact became one of the first medical specialties in American history. It is believed that abortion rates jumped over the 1840-1870 period, and mostly due to married women.

4. Drug companies started to supply their own abortion “remedies” in the 1840s on a much larger scale.

5. At this time there were few moral dilemmas, at least not publicly expressed, about the termination of pregnancies in the earlier stages. That came later in the 20th century.

6. In 1878, a group of physicians in Illinois estimated the general abortion rate at 25%. In any case during this time period abortion was affordable to many more Americans than just the wealthy.

7. Several states started to criminalize abortion during the 1850s.

8. 1857-1880 saw the beginning of a physicians’ crusade against abortion. By 1880, abortion was illegal in most of the United States, and this occurred part and parcel with a rise in the professionalization of the medical profession. These policies were later sustained and extended throughout the 1880s and also the early twentieth century.

9. Over the 1860-1880 period, doctors succeeded in turning American public opinion significantly against abortion. The homeopaths supported them in this.

This is all from the very useful and readable book Abortion in America: The Origins and Evolution of National Policy, by James C. Mohr.

Sunday assorted links

1. Octonions. And a good explanation of why a theory of quantum gravity in particular is needed.

2. Children adopted by lesbian parents do not seem to have excessive rates of mental health problems.

3. Steve Bannon in Europe update.

4. Is a quantum computer less in thrall to the arrow of time?

5. Speculative claims about the Trump doctrine and neoliberalism.

6. Putin’s approval ratings are falling, due to “a deeply unpopular change to pensions.”

Steve Teles on the Federalist Society and the Left

Here is one bit from what is an excellent story with good material in every paragraph:

Mr. Teles makes sure to emphasize that his sympathy with the conservative legal movement here grows out of not his policy preferences, which lean left, but his belief in the importance of a “powerfully structured” constitutional system. “I don’t think the purpose of the Constitution is to get a government so small you can drown in a bathtub,” he says. Rather, it is to ensure the government “is democratically responsible.”

Mr. Teles believes that one of the most salient projects for the newly conservative Roberts Court will be to roll back administrative-state prerogatives. That could revitalize Congress and restore the constitutional structure, vindicating two longtime goals of the conservative legal movement. But he thinks this could also end up serving certain policy ends of progressives.

For the past several decades, Mr. Teles says, many progressive victories in the economic realm have been achieved through “administrative jujitsu”—difficult-to-understand maneuvers involving taxes, fees, mandates, regulations, and administrative directives. If courts start to block technocratic liberal plans for social reform because they violate the separation of powers, the left may find it easier to mobilize for pure redistribution as an alternative. Think of postal banking instead of CFPB regulation, or a carbon tax instead of the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan, or a reduction in the Medicare eligibility age instead of ObamaCare subsidies and exchanges.

That might be good for democratic discourse, Mr. Teles suggests. “In some ways liberalism has been deformed” by relying on administrative agencies, “as opposed to making big arguments for big, encompassing social programs.” In the short term, though, conservative courts will probably prove “radicalizing for the left.” Democrats may fully jettison Clintonism and say: “We’re going straight for socialism.” Steeply redistributive programs enacted by legislatures would be “easier to defend in court,” even a conservative court, than unaccountable bureaucratic diktats.

That is from Jason Willick at the WSJ. I am a big fan of Steve Teles, and in fact here is my Conversation with him (and Brink Lindsey).

Managing Incentives

Lesson one in our textbook chapter on managing incentives is “You get what you pay for (even when what you pay for is not exactly what you want)”. Case in point is the California cleanup of the 2017 wildfires, at $280,000 per site it’s four times more expensive than similar past cleanups and by far the costliest cleanup in CA history. The state emphasized speed and farmed the job out to the Army Corp of Engineers  who hired contractors who were paid by the ton excavated! Paying by the ton created highly u̶n̶p̶r̶e̶d̶i̶c̶t̶a̶b̶l̶e̶ predictable consequences as KQED reports:

who hired contractors who were paid by the ton excavated! Paying by the ton created highly u̶n̶p̶r̶e̶d̶i̶c̶t̶a̶b̶l̶e̶ predictable consequences as KQED reports:

…Dan said he saw workers inflate their load weights with wet mud. Sonoma County Supervisor James Gore said he heard similar stories of subcontractors actually being directed to mix metal that should have been recycled into their loads to make them heavier.

“They [contractors] saw it as gold falling from the sky,” Dan said. “That is the biggest issue. They can’t pay tonnage on jobs like this and expect it to be done safely.”

…Krickl pointed to where his home used to stand. It’s a 6-foot deep depression that he affectionately called his “pond”.

That “pond” was created when contractors removed the foundation, soil and an entire concrete pad for Krickl’s garage, leaving behind a large hole.

Here’s my favorite part:

So many sites were over-excavated that the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services recently launched a new program to refill the holes left behind by Army Corps contractors. That’s estimated to cost another $3.5 million.

Hat tip: Carl D.

Talking to your doctor isn’t about medicine

On average, patients get about 11 seconds to explain the reasons for their visit before they are interrupted by their doctors. Also, only one in three doctors provides their patients with adequate opportunity to describe their situation…

In just over one third of the time (36 per cent), patients were able to put their agendas first. But patients who did get the chance to list their ailments were still interrupted seven out of every ten times, on average within 11 seconds of them starting to speak. In this study, patients who were not interrupted completed their opening statements within about six seconds.

Here is the story, here is the underlying research. Via the excellent Charles Klingman.

Now solve for the telemedicine equilibrium.

Friday assorted links

1. Lagos.

2. “[Low] Rainfall predicts assassinations of Ancient Roman emperors, from 27 BC to 476 AD.”

3. Photographer of death: “It is not known whether Hooper ever aided his subjects.” Warning: those images are tough viewing.

4. Ex post penalty levied on InTrade.

5. Markets in everything? (speculative)

How should the Fed respond to Trump’s comments?

The president tempered his criticism by saying that Chairman Jerome Powell — his own appointee — is a “very good man.” He also stopped short of directly calling on the Fed to stop raising interest rates.

“I’m not thrilled,” he said. “Because we go up and every time you go up they want to raise rates again. I don’t really — I am not happy about it. But at the same time, I’m letting them do what they feel is best.”

Here is the story.

It is probably best for the Fed to simply pretend he did not say this. Trying to respond simply escalates the dispute and risks a repeat comment. That said, the Fed may make its future plans concerning interest rates hazier, thereby offering less forward guidance. That will give Trump less of a target in the short run, and furthermore “the market,” with fuzzier expectations to begin with, won’t be able to estimate whether the Fed was swayed by Trump or not.

In any case, the end result will be a modest increase in economic uncertainty.

I would stress, however, that we do not have a politically independent Fed to begin with. Such an arrangement is impossible in a democracy, given that current institutional protections for the Fed always can be taken away by Congress and the president. What we do have is bounds for independence, and those bounds just narrowed, and not for the better. If I were going to narrow the political independence of the Fed (and I am not advocating this), interest rates are not even the correct variable to choose. Why not some measure of how much the Fed is aiding the economy in a downturn? Interest rates may or may not be the most powerful tool there.

The White House itself is trying to pretend the event didn’t happen:

Shortly afterward, the White House issued a statement saying Trump’s comments were merely a “reiteration” of his “long-held positions,” and that his “views on interest rates are well known.”

“Of course the President respects the independence of the Fed,” it said. “He is not interfering with Fed policy decisions.“

And here is another recent remark by Trump, or was it?

Thursday assorted links

1. Does legalizing marijuana boost housing values?

2. the subtext covers innovation in Africa.

3. Secret life of an autistic stripper.

4. Why people like exaggerated stories.

5. “They also revealed that the eventual decision about who should leave the cave first was not based on strength, but decided by the boys themselves. It was based on who lived furthest away from the cave and therefore would have the longest cycle back home.” Link here.

6. Lawn average is over (WSJ).

My Conversation with Vitalik Buterin

Obviously his talents in crypto and programming are well-known, but he is also a first-rate thinker on both economics and what you broadly might call sociology. You could take away the crypto contributions altogether, and he still would be one of the very smartest people I have met. Here is the audio and transcript. The CWT team summarized it as follows:

Tyler sat down with Vitalik to discuss the many things he’s thinking about and working on, including the nascent field of cryptoeconomics, the best analogy for understanding the blockchain, his desire for more social science fiction, why belief in progress is our most useful delusion, best places to visit in time and space, how he picks up languages, why centralization’s not all bad, the best ways to value crypto assets, whether P = NP, and much more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: If you could go back into the distant past for a year, a time and place of your choosing, you have the linguistic skills and immunity against disease to the extent you need it, maybe some money in your pocket, where would you pick to satisfy your own curiosity?

BUTERIN: Where would I pick? To do what? To spend a year there, or . . . ?

COWEN: Spend a year as a “tourist.” You could pick ancient Athens or preconquest Mexico or medieval Russia. It’s a kind of social science fiction, right?

BUTERIN: Yeah, totally. Let’s see. Possibly first year of World War II — obviously, one of those areas that’s close to it but still reasonably safe from it…

Basically, experience more of what human behavior and what collective human behavior would look like once you pushed humans further into extremes, and people aren’t as comfortable as they are today.

I started the whole dialogue with this:

I went back and I reread all of the papers on your home page. I found it quite striking that there were two very important economics results, one based on menu costs associated with the name of Greg Mankiw. Another is a paper on the indeterminacy of monetary equilibrium associated with Fischer Black.

These are famous papers. On your own, you appear to rediscover these results without knowing about the papers at all. So how would you describe how you teach yourself economics?

Highly recommended, whether or not you understand blockchain. Oh, and there is this:

COWEN: If you had to explain blockchain to a very smart person from 40 years ago, who knew computers but had no idea of crypto, what would be the best short explanation you could give them, basically, for what you do?

BUTERIN: Sure. One of the analogies I keep going back to is this idea of a “world computer.” The idea, basically, is that a blockchain, as a whole, functions like a computer. It has a hard drive, and on that hard drive, it stores what all the accounts are.

It stores what the code of all the smart contracts is, what the memory of all these smart contracts is. It accepts incoming instructions — and these incoming instructions are signed transactions sent by a bunch of different users — and processes them according to a set of rules.

The Misallocation of International Math Talent

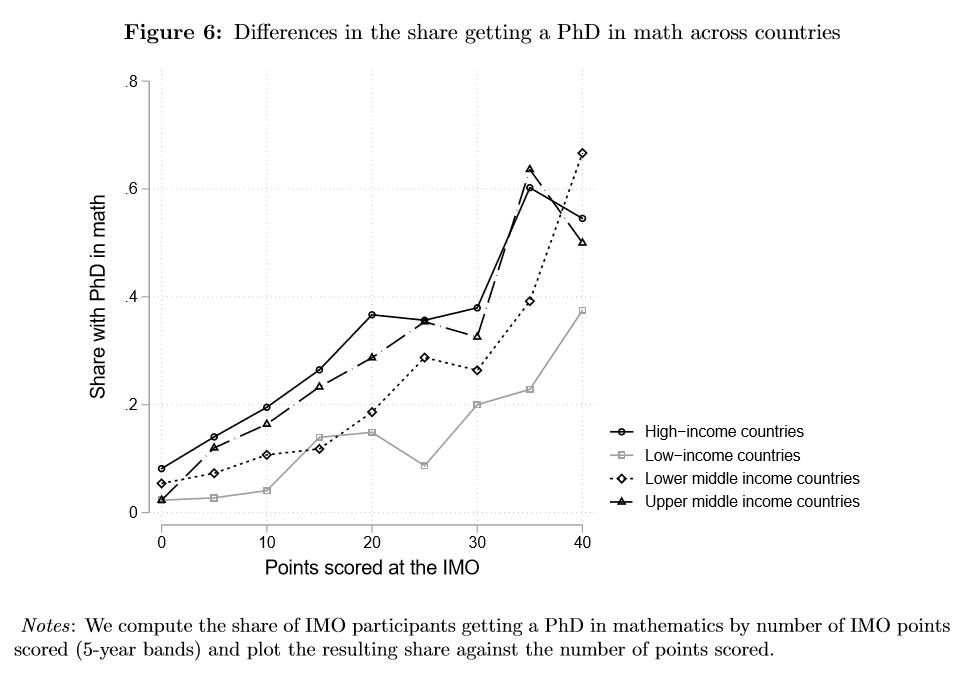

Wealthier countries allocate a greater proportion of their workers to science and engineering, fields which produce ideas that often benefit everyone. This is one reason why we all gain when other countries become rich. It’s not just the number of scientists and engineers that matters, however. In a clever paper, Agarwal and Gaule demonstrate that equally talented people are more productive in wealthier countries.

Agarwal and Gaule collect the scores of thousands of teenagers who entered the International Math Olympiad between 1981 and 2000 and they follow their careers. Every additional point earned at the Olympiad increases the likelihood that a participant will later earn a math PhD, be heavily cited, even earn a Fields medal. But Olympians from poorer countries are less likely to contribute to the mathematical frontier than equally talented teens from richer countries. It could be that smart teens from poorer countries are less likely to pursue a math career–and that could well be optimal–but Agarwal and Gaule find that many of the talented kids from poorer countries simply disappear off the world’s radar. Their talent is wasted.

The post-Olympiad loss is not the largest loss. Most of the potentially great mathematicians from poorer countries are lost to the world long before the opportunity to participate in an Olympiad. But it is frustrating that even after talent has been identified, it does not always bloom. We are, however, starting to do better.

You can see from the graph that upper-middle income countries are as good as turning their talent into results as high-income countries. Agarwal and Gaule also find some evidence that the low-income penalty is diminishing over time.

As incomes increase around the world it’s as if the entire world’s processing power is coming online for the first time in human history. That, at least, is one reason for optimism.

Hat tip: Floridan Ederer.

My take on the Statue of Liberty

That is my latest Bloomberg column, here is one bit:

Cleveland described the statue as “keeping watch and ward before the gates of America.” This is not exactly warm rhetoric — the plaque with Emma Lazarus’s poem welcoming the “huddled masses” to America was not added until 1903 — and although Cleveland supported free trade, he opposed Chinese immigrants, as he regarded them as unable to assimilate. The statue was never about fully open borders.

We Americans tend to think of the statue as reflecting the glories of our national ideals, but that’s not necessarily the case. In her forthcoming “Sentinel: The Unlikely Origins of the Statue of Liberty,” Francesca Lidia Viano points out that you might take the torch and aggressive stance of the statue as a warning to people to go back home, or as a declaration that the U.S. itself needs more light. Her valuable book (on which I am relying for much of the history in this column) also notes that the statue represented an expected “spiritual initiation to liberty” before crossing the border, and was seen as such at the time. The ancient Egyptians, Assyrians and Babylonians all regarded border crossing as an important ritual act, associated with “great spiritual changes.” The Statue of Liberty promoted a transformational and indeed partially mystical interpretation of assimilation.

There are other interpretations of the statue’s purported message based on the details of its design. You plausibly can read the statue as a Masonic icon, a homage to the family coat of arms of Bartholdi the sculptor, a hearkening back to the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, a celebration of Orientalism, Orpheus and Samothracian civilization, and as a monument to the dead of the Revolutionary War. The statue also contained design clues celebrating the now-French city of Colmar (home base for Bartholdi), and threatening revenge against the Germans for taking Colmar in 1871 from the Franco-Prussian war.

And that does not even get us to the main argument. In the meantime, I would stress what a wonderful and splendid book is Francesca Lidia Viano’s Sentinel: The Unlikely Origins of the Statue of Liberty. It is entirely gripping, and one of the must-read non-fiction books of this year.