Results for “age of em” 16698 found

The Invisible Hand of Eco-nomics

Cap and trade is going nowhere at the federal level but the California program is large and expanding and the CA program allows for properly monitored and regulated offsets to be purchased from anywhere in the United States. As a result, a price on carbon is being established nationally. As the NYTimes indicates in a very good article, once a market and a price have been established, contentious politics turns into mutually beneficial economics.

Experts who support cap and trade contend that a market mechanism can reach more deeply into the economy than any other approach, changing the behavior even of people and companies that might not necessarily care about global warming.

The Wisconsin dairymen perhaps serve as an example of that.

Even as the methane-powered generator roared on his property, John T. Pagel said he was not convinced that the climatic changes happening in the United States were a result of human emissions. He suspects they might be part of a natural cycle. But with Californians dangling cash in exchange for his willingness to cut emissions, he jumped at the chance to build his digester.

“We are doing exactly what they asked us to do to get paid to reduce carbon,” Mr. Pagel said. “If somebody else believes in it enough to put up the money, that’s all I need to know.”

Giving away money well can be harder than earning it

Northwestern has a new class method trying to teach that skill:

Vinay Sridharan must make it through microeconomic theory and the writings of Proust before the end of his senior year at Northwestern in June. But in one course, the final project is far less abstract: give away $50,000.

It is also far more difficult than it may seem.

This course in philanthropy, endowed with a grant from a Texas hedge fund manager, requires students to find and investigate nonprofit organizations and, if they stand up to scrutiny, give them a portion of the five-figure cash pot.

But did the backing donor give his money away well? I am not so sure. There is more here.

Score one for the signaling model of education

In the new AER there is a paper by Melvin Stephens Jr. and Dou-Yan Yang, the abstract is this:

Causal estimates of the benefits of increased schooling using US state schooling laws as instruments typically rely on specifications which assume common trends across states in the factors affecting different birth cohorts. Differential changes across states during this period, such as relative school quality improvements, suggest that this assumption may fail to hold. Across a number of outcomes including wages, unemployment, and divorce, we find that statistically significant causal estimates become insignificant and, in many instances, wrong-signed when allowing year of birth effects to vary across regions.

In other words, those semi-natural experiments for the return to education, when some regions move with extra doses of compulsory schooling before others and we estimate differential wage effects, maybe don’t show as much as we used to think. As I’ve remarked to Bryan Caplan, if there is a criticism of a famous or politically correct result (or better yet both) getting published in the AER, you can up your Bayesian priors on that criticism being on the mark.

There are ungated copies of the paper here.

Assorted links

1. Scott Sumner on how to think about France.

2. Three revolutions from Miles Kimball.

3. Why the Germans are still in charge. And Italy’s real problem, in one picture.

4. What is the longest disambiguation page on Wikipedia?

5. My 2011 column on driverless cars.

6. Asian small-clawed otters celebrate enrichment at the Smithsonian.

7. McArdle on Piketty. And check out the cover (!).

Assorted links

1. The evolution of chess openings. Chess openings have become more diverse over time.

2. Modular robots that double as furniture.

3. Piketty responds (again) to the FT. And AFineTheorem on Piketty. And knowhow, dark matter, and Piketty’s capital, from Ricardo Hausmann. And me on Piketty on the radio, transcript.

4. Where to look for your lost mother.

5. Safety vest for chickens (there is no great stagnation). And temporary tattoos hold cooking recipes for ready scrutiny.

6. Amazon responds on Hachette.

Individual NBA players hire statisticians

When will we all?:

Zormelo, who works for individual players and not their teams studies film, pores over metrics, and feeds his clients a mix of information and instruction that is as much informed by Excel spreadsheets as it is by coaches’ playbooks. He gives players data and advice on obscure points of the game — something many coaches may not appreciate — like their offensive production when they take two dribbles instead of four and their shooting percentages when coming off screens at the left elbow of the court.

There is more here, via @EdwardGarnett. Kevin Durant and John Wall are two of his better-known employers. The NBA coaches, by the way, are not necessarily informed about Zormelo’s work.

More cars, fewer pedestrian deaths

Michael Blastland and David Spiegelhalter have a new book about risk — The Norm Chronicles: Stories and Numbers About Dangers and Death — and it does actually have new material on what is by now a somewhat worn out topic. Here is one example:

In 1951 there were fewer than 4 million registered vehicles on the roads in Britain. They meandered the highways free of restrictions such as road markings, traffic calming, certificates for roadworthiness, or low-impact bumpers. Children played in the streets and walked to school. The result was that 907 children under 15 were killed on the roads in 1951, including 707 pedestrians and 130 cyclists. Even this was less than the 1,400 a year killed before the war.

The carnage had dropped to 533 child deaths in 1995, to 124 in 2008, to 81 in 2009, and in 2010 to 55 — each a tragedy for the family, but still a staggering 90 percent fall over 60 years.

You can buy the book here.

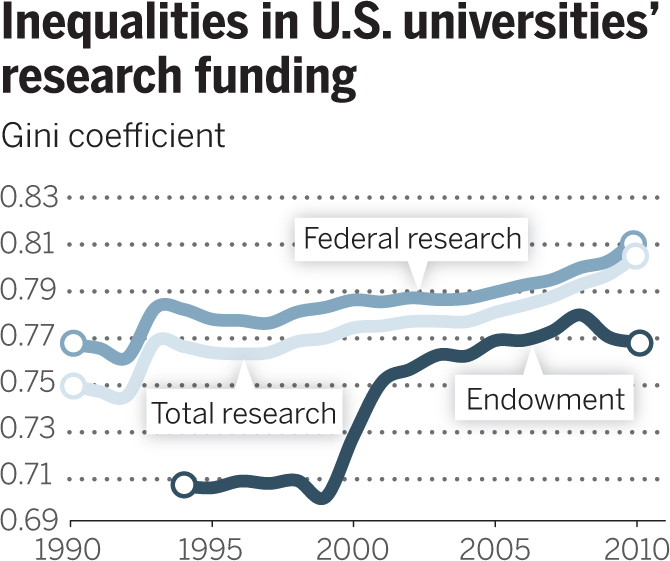

Gini coefficient for U.S. universities

For the pointer I thank J.O.

Assorted links

1. Clever birds figure out automatic door.

2. Japanese book on how to use profanity correctly in English. And other methods of Japanese quality improvement.

3. Entropy and inequality (speculative, possibly downright dubious).

4. Why the European left is collapsing (speculative and overblown, but also makes some good points).

5. Why restitution should be small (a 2002 essay by me).

6. “Let’s, Like, Demolish Laundry.”

7. More Galbraith on Piketty. Nate Silver on Piketty and data.

8. And very very sadly the Mackintosh library in Glasgow has been destroyed by fire.

Markets in everything the packing culture that is New York

The division of labor is indeed limited by the extent of the market:

New York City mommies with money to burn are hiring professional organizers to pack their kids’ trunks for summer camp — because their darlings can’t live without their 1,000-thread-count sheets.

Barbara Reich of Resourceful Consultants says she and other high-paid neat freaks have been inundated with requests — and the job is no small feat.

It takes three to four hours to pack for clients who demand that she fit all of the comforts of home in the luggage, including delicate touches like French-milled soaps and scented candles.

At $250 an hour, the cost for a well-packed kid can run $1,000.

There is more here, via the excellent Mark Thorson.

The EU parliamentary elections

One headline is this:

The far right anti-EU National Front was forecast to win a European Parliament election in France on Sunday, topping a nationwide ballot for the first time in a stunning advance for opponents of European integration.

I’ve long maintained two points:

1. The eurozone crisis, in purely economic terms, was always salvageable. Monetary policy hasn’t much been used actively, the latent OMT semi-commitment more or less worked, and debt to gdp levels for the eurozone as a whole have never been worse than those of the United States, to cite a few simple facts.

2. Saving the eurozone requires a lot of political coordination, and a lot of intra-zone wealth redistribution, in a manner which I thought was unlikely to be initiated or maintained.

Since I’ve never been convinced that #2 is workable, I’ve not yet had a “I guess I’m wrong about the implosion of the eurozone” moment. You may recall my earlier prediction: “”Enter democracy, stage right” is the next act in the play.”

“We all know that wealth inequality has gone up”

That is a response to the Piketty criticisms from Paul Krugman, and also mentioned by Matt Yglesias. Phiip Pilkington also has a useful treatment. This point however doesn’t do the trick as a defense. Keep in mind that the “new and improved numbers,” as produced by Chris Giles, are showing doubts about the course of measured wealth inequality in the UK. Maybe wealth inequality hasn’t gone up.

Now maybe that does “have to be wrong.” But if the “new and improved” numbers are wrong, it is hard to then argue Piketty’s wealth inequality numbers can be trusted. In which case we are back to knowing that income inequality has gone up, but not knowing so much concrete about wealth inequality. (That is one reason why my own Average is Over focuses on income, and on labor income in particular, because that is where the main action has been.) The data section of Piketty’s book, which has gathered so much praise, then is not so useful, though by no fault of Piketty’s. We might think it likely that wealth inequality has gone up, but if we are going to do these selective overrides of the best available data, we cannot trust the data so much period or otherwise cite it with authority. We also could not map wealth inequality into particular measures of the r vs. g gap at various periods of time.

If there is one big lesson of the FT/Piketty dust-up, it is that we don’t have reliable numbers on wealth inequality.

Now do we in fact “know” that wealth inequality has gone up? See this piece by Allison Schrager. Intuitions about wealth vs. income inequality are trickier than you might think. And on what we actually do and do not know, here is a very good comment on Mian and Sufi’s blog (for U.S. data):

How much have white Americans benefited from slavery and its legacy?

Many people are talking about the Ta-Nehisi Coates essay on reparations. Ezra Klein has a summary of the argument, which runs as follows:

What Coates shows is that white America has, for hundreds of years, used deadly force, racist laws, biased courts and housing segregation to wrest the power of compound interest for itself. The word he keeps coming back to is “plunder.” White America built its wealth by stealing the work of African-Americans and then, when that became illegal, it added to its wealth by plundering from the work and young assets of African-Americans. And then, crucially, it let compound interest work its magic.

I would suggest that most living white Americans would be wealthier had this nation not enslaved African-Americans and thus most whites have lost from slavery too, albeit much much less than blacks have lost. For instance it is generally recognized that freer and fairer polities tend to be wealthier for most of their citizens. (We may disagree about what “fair” means for many issues, but slavery and its legacy are obviously unfair.)

More specifically, many American whites benefited from hiring African-American labor at discrimination-laden discounted market prices, but many others lost out because it was more costly to trade with African-Americans. That meant fewer good customers, fewer eligible employees, fewer possible business partners, fewer innovators, and so on, all because of slavery and subsequent discrimination. The wealth-destroying effects are surely much larger here, even counting whites alone. And the longer the time horizon, the more likely the dynamic benefits from trade will outweigh the short-run benefits from discriminating against some class of others.

Empirically, I do not think whites in slavery-heavy regions have had especially impressive per capita incomes. And a lot of the economic catch-up of the American South came only when the region abandoned Jim Crow.

We also can look at how many white Americans have had ancestors who, at least for a while, had zero or near-zero net wealth. The returns from slavery may have been compounding for some heirs of Mississippi plantation owners, but not for most of us. My father, when he was thirty, had just gone bankrupt from an unsuccessful attempt to manage a New Jersey pet store. In what sense was he, or later I, reaping compound returns from a legacy of slavery? We go back to the point that overall he probably would have had a better chance in the wealthier and fairer non-discriminating society, even if you can pinpoint some mechanisms through which he might have benefited, such as facing less competition from potential African-American pet store entrepreneurs.

The economic incidence of slavery is a tricky matter (most of what Squarely Rooted argues here is wrong). A lot of whites in the slave trade bought slaves at the going market price and earned the going market rate of return. Of course these same whites were reluctant to free the slaves they had bought and that meant terrible lives for the victims. But the gains of those whites are not mirror images of the losses of the slaves. Thus in some regards slavery was a massive collective action problem with a relatively small number of beneficiaries. Those benefiting would include individuals who first saw the gains from seizing slaves from Africa, and individuals who were good at spotting undervalued slaves and buying them up and exploiting them. That’s a fair number of people but it is far from comprising the overwhelming majority of society in 1840, much less 1940 or 2014, once we consider possible wealth transmission to their heirs.

There is still a moral case for reparations even if most American whites have lost from slavery rather than benefited. (Although I doubt if the America public would see the matter that way, which is one reason why the reparations movement probably isn’t going anywhere.) Nonetheless on the economics of the issue I would suggest a very different analysis than what I am seeing from many of the commentators. And this analysis makes slavery out to be all the more destructive, and reparations to be all the more unlikely.

Addendum: It is amazing how many of you cannot read and digest a simple sentence such as “There is still a moral case for reparations even if most American whites have lost from slavery rather than benefited.” Which by the way is far to the “left” of where the current debate stands in American politics and indeed in most other parts of the world.

*The Supermodel and the Brillo Box*

The author is Don Thompson and the subtitle is Back Stories and Peculiar Economics from the World of Contemporary Art. It is a very enjoyable book on the economics of the contemporary art world, here is one bit:

The size of his art empire allows Gagosian to take full advantage of the economic oddity that when an artist is hot, the relationship of supply and demand reverses. If an artist creates enough work to show simultaneously in several galleries and at several art fairs, greater buzz produces higher prices. Each show, each fair, each art magazine mention produces more critical appraisal, more buzz, and more collectors on the waiting list. The reassurance of the dealer is reinforced by the behavior of the crowd. Greater supply produces greater demand.

Andy Warhol was one of the artists who understood this best.

Piketty update

…according to a Financial Times investigation, the rock-star French economist appears to have got his sums wrong.

The data underpinning Professor Piketty’s 577-page tome, which has dominated best-seller lists in recent weeks, contain a series of errors that skew his findings. The FT found mistakes and unexplained entries in his spreadsheets, similar to those which last year undermined the work on public debt and growth of Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff.

The central theme of Prof Piketty’s work is that wealth inequalities are heading back up to levels last seen before the first world war. The investigation undercuts this claim, indicating there is little evidence in Prof Piketty’s original sources to bear out the thesis that an increasing share of total wealth is held by the richest few.

Prof Piketty, 43, provides detailed sourcing for his estimates of wealth inequality in Europe and the US over the past 200 years. In his spreadsheets, however, there are transcription errors from the original sources and incorrect formulas. It also appears that some of the data are cherry-picked or constructed without an original source.

For example, once the FT cleaned up and simplified the data, the European numbers do not show any tendency towards rising wealth inequality after 1970. An independent specialist in measuring inequality shared the FT’s concerns.

The full FT story is here.

Addendum: Here is the in-depth discussion. Here is Piketty’s response.

I could not have said it better myself.