Results for “department why not” 205 found

More British DOGE

Sir Keir Starmer is abolishing NHS England as Labour embarks on the biggest reorganisation of the health service for more than a decade.

The prime minister said that scrapping the arm’s-length body would bring “management of the NHS back into democratic control” and reduce spending on “two layers of bureaucracy”.

He said the quango, responsible for the day-to-day running of the health service, was the ultimate example of “politicians almost not trusting themselves, outsourcing everything to different bodies … to the point you can’t get things done”.

Starmer argued: “I don’t see why the decision about £200 billion of taxpayer money on something as fundamental to our security as the NHS should be taken by an arm’s-length body.”

NHS England will now be brought back under the control of the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), and the two organisations will be merged over the next two years, leading to about 10,000 job cuts.

Here is more from the Times of London.

The Trump Administration’s Attack on Science Will Backfire

The Trump administration is targeting universities for embracing racist and woke ideologies, but its aim is off. The problem is that the disciplines leading the woke charge—English, history, and sociology—don’t receive much government funding. So the administration is going after science funding, particularly the so-called “overhead” costs that support university research. This will backfire for four reasons.

First, the Trump administration appears to believe that reducing overhead payments will financially weaken the ideological forces in universities. But in reality, science overhead doesn’t support the humanities or social sciences in any meaningful way. The way universities are organized, science funding mostly stays within the College of Science to pay for lab space, research infrastructure, and scientific equipment. Cutting these funds won’t defund woke ideology—it will defund physics labs, biomedical research, and engineering departments. The humanities will remain relatively untouched.

Second, science funding supports valuable research, from combating antibiotic resistance to curing cancer to creating new materials. Not all funded projects are useful, but the returns to R&D are high. If we err it is in funding too little rather than too much. The US is a warfare-welfare state when it should be an innovation state. If you want to reform education, repeal the Biden student loan programs that tax mechanical engineers and subsidize drama majors.

Third, if government science funding subsidizes anyone, it’s American firms. Universities are the training grounds for engineers and scientists, most of whom go on to work for U.S. companies. Undermining science funding weakens this pipeline, ultimately harming American firms rather than striking a blow at wokeness. One of the biggest failings of the Biden administration were its attacks on America’s high-tech entrepreneurial firms. Why go after Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Meta when these are among our best, world-beating firms? But you know what other American sector is world-beating? American universities. The linkage is no accident.

Fourth, scientists are among the least woke academics. Most steer clear of activism, and many view leftist campus culture with skepticism. The STEM fields are highly meritocratic and reality-driven. By undermining science, the administration is weakening one of America’s leading meritocratic sectors. The long run implications of weakening meritocracy are not good. Solve for the equilibrium.

In short, going after science funding is a self-defeating strategy. If conservatives want to reform higher education, they need a smarter approach.

Hat tip: Connor.

Friday assorted links

1. Using AI to cut government spending.

2. “I built RPLY to never miss a text again. Staying in touch should be effortless—RPLY finds your unanswered texts, instantly suggests AI-powered drafts, and syncs across all your Apple devices, meeting you where you already are.” Link here. Techcrunch article here. Much more of this on the way.

3. Katherine Rundell on children’s books.

4. Allen Sanderson has passed away.

5. The Trump Executive Orders as radical constitutionalism?

6. High school summer program at Princeton and Swarthmore.

7. Comments on US AID and its current status.

8. Fast-track approvals starts for New Zealand.

10. Fergus annotates my Conversation with Ross Douthat, from an Evangelical Christian point of view.

Trumpian policy as cultural policy

The Trump administration has issued a blizzard of Executive Orders, and set many other potential changes in the works. They might rename Dulles Airport (can you guess to what?). A bill has been introduced to add you-know-who to Mount Rushmore. There is DOGE, and the ongoing attempt to reshape federal employment.

At the same time, many people have been asking me why Trump chose Canada and Mexico to threaten with tariffs — are they not our neighbors, major trading partners, and closest allies?

I have a theory that tries to explain all these and other facts, though many other factors matter too. I think of Trumpian policy, first and foremost, as elevating cultural policy above all else.

Imagine you hold a vision where the (partial) decline of America largely is about culture. After all, we have more people and more natural resources than ever before. Our top achievements remain impressive. But is the overall culture of the people in such great shape? The culture of government and public service? Interest in our religious organizations? The quality of local government in many states? You don’t have to be a diehard Trumper to have some serious reservations on such questions.

We also see countries, such as China, that have screwed-up policies but have grown a lot, in large part because of a pro-business, pro-learning, pro-work culture. Latin America, in contrast, did lots of policy reforms but still is somewhat stagnant.

OK, so how might you fix the culture of America? You want to tell everyone that America comes first. That America should be more masculine and less soft. That we need to build. That we should “own the libs.” I could go on with more examples and details, but this part of it you already get.

So imagine you started a political revolution and asked the simple question “does this policy change reinforce or overturn our basic cultural messages?” Every time the policy or policy debate pushes culture in what you think is the right direction, just do it. Do it in the view that the cultural factors will, over some time horizon, surpass everything else in import.

Simply pass or announce or promise such policies. Do not worry about any other constraints.

You don’t even have to do them!

They don’t even all have to be legal! (Illegal might provoke more discussion.)

They don’t all have to persist!

You create a debate over the issues knowing that, because of polarization, at least one-third of the American public is going to take your side, sometimes much more than that. These are your investments in changing the culture. And do it with as many issues as possible, as quickly as possible (reread Ezra on this). Think of it as akin to the early Jordan Peterson cranking out all those videos. Flood the zone. That is how you have an impact in an internet-intensive, attention-at-a-premium world.

You will not win all of these cultural debates, but you will control the ideological agenda (I hesitate to call it an “intellectual” agenda, but it is). Your opponents will be dispirited and disorganized, and yes that does describe the Democrats today. Then just keep on going. In the long run, you may end up “owning” far more of the culture than you suspected was possible.

Yes policy will be a mess, but as they say “man kann nicht alles haben.” The culture is worth a lot, both for its own sake and as a predictor of the future course of policy.

Now let’s turn to some details.

In the first week, Trump makes a huge point of striking down DEI and affirmative action (in some of its forms) as the very beginnings of his administration. The WSJ described it as the centerpiece of his program. Take origins seriously!

Early on, we also see so many efforts to make statements about the culture wars. Trans issues, for instance trans out of the military. No more “Black History Month” for the Department of Defense. There are more of these than I can keep track of, use Perplexity if you must.

It is no accident that these are priorities. And keep in mind the main point is not to eliminate Black History Month, though I do not doubt that is a favored policy. The main point is to get people talking about how you are eliminating Black History Month. Just as I am covering the topic right now.

How is that war against US AID going? Will it be abolished? Cut off from the Treasury payments system? Simply rolled up into the State Department? Presidential “impoundment” invoked? I do not know. Perhaps nobody knows, not yet. The point however is to delegitimatize what US AID stands for, which the Trumpers perceive as “other countries first” and a certain kind of altruism, and a certain kind of NGO left-leaning mindset and lifestyle.

The core message is simply “we do not consider this legitimate.” Have that be the topic of discussion for months, and do not worry about converting each and every debate into an immediate tangible victory.

What about those ridiculous nominations, starting with RFK, Jr.? As a result of the nomination, people start questioning whether the medical and public health establishments are legitimate after all. And once such a question starts being debated, the answer simply cannot come out fully positive, whatever the details of your worldview may be. People end up in a more negative mental position, and of course then some negative contagion reinforces this further.

JFK and UAP dislcosure? The point is to get people questioning the previous regime, why they kept secrets from us, what really was going on with many other issues, and so on. It will work. The good news, if you can call it that, is that we can expect some of the juicier secrets to be made public.

I think by now you can see how the various attempts to restructure federal employment fit into this picture. And Trump’s “war against universities” has barely begun, but stay tuned. Don’t even get me going on “Gaza real estate,” the very latest.

Finally, let’s return to those tariffs (non-tariffs?) on Canada and Mexico. We already know Trump believes in tariffs, and yes that is a big factor, but why choose those countries in particular? Well, first it is a symbol of strength and Trump’s apparent ability to ignore and contradict mainstream opinion. But also those are two countries most Americans have heard of. If Trump announced high tariffs on say Burundi, most people would have no idea what it means. They would not know how to debate it, and they would not know if America was debasing itself or thumbing its nose at somebody, or whatever.

Canada and Mexico gets the cultural point across. Canada, all the more so, and thus the Canadian tariffs might be harder to truly reverse. At least to many Yankee outsiders, Canada comes across as exactly the kind of “wuss” country we need to distance ourselves from.

To be clear, this hypothesis does not not not require any kind of cohesive elite planning the whole strategy (though there are elites planning significant parts of what Trump is doing). It suffices to have a) conflicting interest groups, b) competition for Trump’s attention, and c) Trump believing cultural issues are super-important, as he seems to. There then results a spontaneous order, in which the visible strategy looks just like someone intended exactly this as a concrete plan.

In a future post I may consider the pluses and minuses of this kind of political/cultural strategy.

The Cows in the Coal Mine

I remain stunned at how poorly we are responding to the threat from H5N1. Our poor response to COVID was regrettable but perhaps understandable given the US hadn’t faced a major pandemic in decades. Having been through COVID, however, you would think that we would be primed. But no. Instead of acting aggressively to stop the spread in cows we took a gamble that avian flu would fizzle out. It didn’t. California dairy herds are now so awash in flu that California has declared a state of emergency. Hundreds of herds across the United States have been infected.

I don’t think we are getting a good picture of what is happening to the cows because we don’t like to look too closely at our food supply. But I reported in September what farmers were saying:

The cows were lethargic and didn’t move. Water consumption dropped from 40 gallons to 5 gallons a day. He gave his cows aspirin twice a day, increased the amount of water they were getting and gave injections of vitamins for three days.

Five percent of the herd had to be culled.

“They didn’t want to get up, they didn’t want to drink, and they got very dehydrated,” Brearley said, adding that his crew worked around the clock to treat nearly 300 cows twice a day. “There is no time to think about testing when it hits. You have to treat it. You have sick cows, and that’s our job is to take care of them.”

Here’s another report from a vet:

…the scale of the farmers’ efforts to treat the sick cows stunned him. They showed videos of systems they built to hydrate hundreds of cattle at once. In 14-hour shifts, dairy workers pumped gallons of electrolyte-rich fluids into ailing cows through metal tubes inserted into the esophagus.

“It was like watching a field hospital on an active battlefront treating hundreds of wounded soldiers,” he said.

Here’s Reuters:

Cows in California are dying at much higher rates from bird flu than in other affected states, industry and veterinary experts said, and some carcasses have been left rotting in the sun as rendering plants struggle to process all the dead animals.

…Infected herds in California are seeing mortality rates as high as 15% or 20%, compared to 2% in other states, said Keith Poulsen, a veterinarian and director of the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory who has researched bird flu.

The California Department of Food and Agriculture did not respond to questions about the mortality rate from bird flu.

Does this remind you of anything? Must we wait until the human morgues are overrun?

The case fatality rate for cows appears to be low but significant, perhaps 2%. A small number of pigs have also been infected. On the other hand, over 100 million chickens, turkeys and ducks have been killed or culled.

There have now been 66 cases in humans in the US. Moreover, the CDC reports that in at least one case the virus appears to have evolved within its human host to become more infectious. We don’t know that for sure but it’s not good news. Recall that in theory a single mutation will make the virus much more capable of infecting humans.

When I wrote on December 1 that A Bird Flu Pandemic Would Be One of the Most Foreseeable Catastrophes in History Manifold Markets was predicting a 9% probability of greater than 1 million US human cases in 2025. Today the prediction is at 20%.

Once again, we may get lucky and that is still the way to bet but only the weak rely on luck. Strong civilizations don’t pray for luck. They crush the bugs. So far, we are not doing that.

Happy new year.

My Conversation with the excellent Christopher Kirchhoff

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the intro:

Christopher Kirchhoff is an expert in emerging technology who founded the Pentagon’s Silicon Valley office. He’s led teams for President Obama, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and CEO of Google. He’s worked in worlds as far apart as weapons development and philanthropy. His pioneering efforts to link Silicon Valley technology and startups to Washington has made him responsible for $70 billion in technology acquisition by the Department of Defense. He’s penned many landmark reports, and he is the author of Unit X: How the Pentagon and Silicon Valley are Transforming the Future of War.

Tyler and Christopher cover the ascendancy of drone warfare and how it will affect tactics both off and on the battlefield, the sobering prospect of hypersonic weapons and how they will shift the balance of power, EMP attacks, AI as the new arms race (and who’s winning), the completely different technology ecosystem of an iPhone vs. an F-35, why we shouldn’t nationalize AI labs, the problem with security clearances, why the major defense contractors lost their dynamism, how to overcome the “Valley of Death” in defense acquisition, the lack of executive authority in government, how Unit X began, the most effective type of government commission, what he’ll learn next, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: Now, I never understand what I read about hypersonic missiles. I see in the media, “China has launched the world’s first nuclear-capable hypersonic, and it goes 10x the speed of sound.” And people are worried. If mutual assured destruction is already in place, what exactly is the nature of the worry? Is it just we don’t have enough response time?

KIRCHHOFF: It’s a number of things, and when you add them up, they really are quite frightening. Hypersonic weapons, because of the way they maneuver, don’t necessarily have to follow a ballistic trajectory. We have very sophisticated space-based systems that can detect the launch of a missile, particularly a nuclear missile, but right then you’re immediately calculating where it’s going to go based on its ballistic trajectory. Well, a hypersonic weapon can steer. It can turn left, it can turn right, it can dive up, it can dive down.

COWEN: But that’s distinct from hypersonic, right?

KIRCHHOFF: Well, ICBMs don’t have the same maneuverability. That’s one factor that makes hypersonic weapons different. Second is just speed. With an ICBM launch, you have 20 to 25 minutes or so. This is why the rule for a presidential nuclear decision conference is, you have to be able to get the president online with his national security advisers in, I think, five or seven minutes. The whole system is timed to defeat adversary threats. The whole continuity-of-government system is upended by the timeline of hypersonic weapons.

Oh, by the way, there’s no way to defend against them, so forget the fact that they’re nuclear capable — if you want to take out an aircraft carrier or a service combatant, or assassinate a world leader, a hypersonic weapon is a fantastic way to do it. Watch them very carefully because more than anything else, they will shift the balance of military power in the next five years.

COWEN: Do you think they shift the power to China in particular, or to larger nations, or nations willing to take big chances? At the conceptual level, what’s the nature of the shift, above and beyond whoever has them?

KIRCHHOFF: Well, right now, they’re incredibly hard to produce. Right now, they’re essentially in a research and development phase. The first nation that figures out how to make titanium just a little bit more heat resistant, to make the guidance systems just a little bit better, and enables manufacturing at scale — not just five or seven weapons that are test-fired every year, but 25 or 50 or 75 or 100 — that really would change the balance of power in a remarkable number of military scenarios.

COWEN: How much China has them now? Are you at liberty to address that? They just have one or two that are not really that useful, or they’re on the verge of having 300?

KIRCHHOFF: What’s in the media and what’s been discussed quite a bit publicly is that China has more successful R&D tests of hypersonic weapons. Hypersonic weapons are very difficult to make fly for long periods. They tend to self-destruct at some point during flight. China has demonstrated a much fuller flight cycle of what looks to be an almost operational weapon.

COWEN: Where is Russia in this space?

KIRCHHOFF: Russia is also trying. Russia is developing a panoply of Dr. Evil weapons. The latest one to emerge in public is this idea of putting a nuclear payload on a satellite that would effectively stop modern life as we know it by ending GPS and satellite communications. That’s really somebody sitting in a Dr. Evil lair, stroking their cat, coming up with ideas that are game-changing. They’ve come up with a number of other weapons that are quite striking — supercavitating torpedoes that could take out an entire aircraft carrier group. Advanced states are now coming up with incredibly potent weapons.

Intelligent and interesting throughout. Again, I am happy to recommend Christopher’s recent book Unit X: How the Pentagon and Silicon Valley are Transforming the Future of War, co-authored with Raj M. Shah.

From the comments (on regulation)

The Pentagon’s Anti-Vax Campaign

During the pandemic it was common for many Americans to discount or even disparage the Chinese vaccines. In fact, the Chinese vaccines such as Coronavac/Sinovac were made quickly and in large quantities and they were effective. The Chinese vaccines saved millions of lives. The vaccine portfolio model that the AHT team produced, as well as common sense, suggested the value of having a diversified portfolio. That’s why we recommended and I advocated for including a deactivated vaccine in the Operation Warp Speed mix or barring that for making an advance deal on vaccine capacity with China. At the time, I assumed that the disparaging of Chinese vaccines was simply an issue of national pride or bravado during a time of fear. But it turns out that in other countries, the Pentagon ran a disinformation campaign against the Chinese vaccines.

Reuters: At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. military launched a secret campaign to counter what it perceived as China’s growing influence in the Philippines, a nation hit especially hard by the deadly virus.

The clandestine operation has not been previously reported. It aimed to sow doubt about the safety and efficacy of vaccines and other life-saving aid that was being supplied by China, a Reuters investigation found. Through phony internet accounts meant to impersonate Filipinos, the military’s propaganda efforts morphed into an anti-vax campaign.

… Tailoring the propaganda campaign to local audiences across Central Asia and the Middle East, the Pentagon used a combination of fake social media accounts on multiple platforms to spread fear of China’s vaccines among Muslims at a time when the virus was killing tens of thousands of people each day. A key part of the strategy: amplify the disputed contention that, because vaccines sometimes contain pork gelatin, China’s shots could be considered forbidden under Islamic law.

…To implement the anti-vax campaign, the Defense Department overrode strong objections from top U.S. diplomats in Southeast Asia at the time, Reuters found. Sources involved in its planning and execution say the Pentagon, which ran the program through the military’s psychological operations center in Tampa, Florida, disregarded the collateral impact that such propaganda may have on innocent Filipinos.

“We weren’t looking at this from a public health perspective,” said a senior military officer involved in the program. “We were looking at how we could drag China through the mud.”

Frankly, this is sickening. The Pentagon’s anti-vax campaign has undermined U.S. credibility on the global stage and eroded trust in American institutions, and it will complicate future public health efforts. US intelligence agencies should be banned from interfering with or using public health as a front.

Moreover, there was a better model. It’s often forgotten but the elimination of smallpox from the planet, one of humanities greatest feats, was a global effort spearheaded by the United States and….the Soviet Union.

…even while engaged in a pitched battle for influence across the globe, the Soviet Union and the United States were able to harness their domestic and geopolitical self-interests and their mutual interest in using science and technology to advance human development and produce a remarkable public health achievement.

We could have taken a similar approach with China during the COVID pandemic.

More generally, we face global challenges, from pandemics to climate change to artificial intelligence. Addressing these challenges will require strategic international cooperation. This isn’t about idealism; it’s about escaping the prisoner’s dilemma. We can’t let small groups with narrow agendas and parochial visions undermine collaborations essential for our interests and security in an interconnected world.

Get Out of Jail Cards, 2

“Courtesy cards,” are cards given out by the NYC police union (and presumably elsewhere) to friends and family who use them to get easy treatment if they are pulled over by a cop. I was stunned when I first wrote about these cards in 2018. I thought this was common only in tinpot dictatorships and flailing states. The cards even come in levels, gold, silver and bronze!

A retired police officer on Quora explains how the privilege is enforced:

The officer who is presented with one of these cards will normally tell the violator to be more careful, give the card back, and send them on their way.

…The other option is potentially more perilous. The enforcement officer can issue the ticket or make the arrest in spite of the courtesy card. This is called “writing over the card.” There is a chance that the officer who issued the card will understand why the enforcement officer did what he did, and nothing will come of it. However, it is equally possible that the enforcement officer’s zeal will not be appreciated, and the enforcement officer will come to work one day to find his locker has been moved to the parking lot and filled with dog excrement.

A NYTimes article discusses the case of Mathew Bianchi, a traffic cop who got sick of letting dangerous speeders go when they presented their cards.

By the time he pulled over the Mazda in November 2018, drivers were handing Bianchi these cards six or seven times a day. (!!!, AT)

…[He gives the ticket]…The month after he stopped the Mazda, a high-ranking police union official, Albert Acierno, got in touch. He told Bianchi that the cards were inviolable. He then delivered what Bianchi came to think of as the “brother speech,” saying that cops are brothers and must help each other out. That the cards were symbols of the bonds between the police and their extended family and friends.

Bianchi was starting to view the cards as a different kind of symbol: of the impunity that came with knowing someone on the force, as if New York’s rules didn’t apply to those with connections. Over the next four years, he learned about the unwritten rules that have come to hold sway in the Police Department.

Bianchi is reassigned, given shit jobs, isn’t promoted etc. Mayor Adams and police chief Chief Maddrey protect this utterly corrupt system.

Top MR Posts of 2023

This was the year of AI; including the top post from Tyler, Existential risk, AI, and the inevitable turn in human history but also highly ranked were my posts AGI is Coming and AI Worship and Tyler’s GPT and my own career trajectory. Also our paper, How to Learn and Teach Economics with Large Language Models, Including GPT has now been downloaded more than ten thousand times.

2. Second most popular post was The Extreme Shortage of High IQ Workers

5. *GOAT: Who is the Greatest Economist of all Time, and Why Does it Matter?*

6. Matt Yglesias on depression and political ideology which pairs well with another highly-ranked Tyler post, So what is the right-wing pathology then? and also Classical liberals are increasingly religious.

7. Can the SVB crisis be solved in the longer run?

8. Substitutes Are Everywhere: The Great German Gas Debate in Retrospect

9. My paean to Costco.

10. Is Bach the greatest achiever of all time?

11. The Real Secret of Blue Zones

12. SpaceX Versus the Department of Justice

13. What does it mean to understand how a scientific literature is put together?

14. In Praise of the Danish Mortgage System

15. Great News for Female Academics!

Finally, don’t forget Tyler’s posts Best non-fiction books of 2023, Favorite fiction books of 2023, and Favorite non-classical music.

What were your favorite posts/articles/books/music/movies of 2023?

The University presidents

Here is three and a half minutes of their testimony before Congress. Worth a watch, if you haven’t already. I have viewed some other segments as well, none of them impressive. I can’t bring myself to sit through the whole thing.

I don’t doubt that I would find their actual views on world affairs highly objectionable, but that is not why I am here today. Here are a few other points:

1. Their entire testimony is ruled by their lawyers, by their fear that their universities might be sued, and their need to placate internal interest groups. That is a major problem, in addition to their unwillingness to condemn various forms of rhetoric for violating their codes of conduct. As Katherine Boyle stated: “This is Rule by HR Department and it gets dark very fast.”

How do you think that affects the quality of their other decisions? The perceptions and incentives of their subordinates?

2. They are all in a defensive crouch. None of them are good on TV. None of them are good in front of Congress. They have ended up disgracing their universities, in front of massive audiences (the largest they ever will have?), simply for the end goal of maintaining a kind of (illusory?) maximum defensibility for their positions within their universities. At that they are too skilled.

How do you think that affects the quality of their other decisions? The perceptions and incentives of their subordinates?

What do you think about the mechanisms that led these particular individuals to be selected for top leadership positions?

3. Not one came close to admitting how hypocritical private university policies are on free speech. You can call for Intifada but cannot express say various opinions about trans individuals. Not de facto. Whether you think they should or not, none of these universities comes close to enforcing “First Amendment standards” for speech, even off-campus speech for their faculty, students, and affiliates.

What do you think that says about the quality and forthrightness of their other decisions? Of the subsequent perceptions and incentives of their subordinates?

What do you think about the mechanisms that led this particular equilibrium to evolve?

Overall this was a dark day for American higher education. I want you to keep in mind that the incentives you saw on display rule so many other parts of the system, albeit usually invisibly. Don’t forget that. These university presidents have solved for what they think is the equilibrium, and it ain’t pretty.

Malthus was smarter than you think, vice and prostitution edition

That is a passage from my new book GOAT: Who is the Greatest Economist of all Time and Why Does it Matter?

So one way to read Malthus is this: if a society is going to have any prosperity at all, the people in that society either will be morally quite bad, or they have to be morally very, very good, good enough to exercise that moral restraint. Alternatively, you can read Malthus as seeing two primary goals for people: food and sex. His accomplishment was to show that, taken collectively, those two goals could not easily be obtainable simultaneously in a satisfactory fashion. In late Freudian terms, you could say that eros/sex amounts to the death drive, but again painted on a collective canvas and driven by economic mechanisms.

Malthus also hinted at birth control as an important social and economic force, especially later in 1817, putting him ahead of many other thinkers of his time. Birth control was widely practiced for centuries through a variety of means, and Malthus unfortunately was not very specific. He did call it “unnatural,” and the mainstream theology of his Anglican church condemned it, as did many other churches. But what did he really think? Was this unnatural practice so much worse than the other alternatives of misery and vice that his model was putting forward? Or did Malthus simply fail to see that birth control could be so effective and widespread as it is today? It doesn’t seem we are ever going to know.

From Malthus’s tripartite grouping of vice, moral restraint, and misery, two things should be clear immediately. The first is why Keynes found Malthus so interesting, namely that homosexual passions are one (partial) way out of the Malthusian trap. The second is that there is a Straussian reading of Malthus, namely that he thought moral restraint, while wonderful, was limited in its applicability. So maybe then vice wasn’t so bad after all? Is it not better than war and starvation?

I don’t buy the Straussian reading as a description of what Malthus really meant. But he knew it was there, and he knew he was forcing you to think about just how bad you thought vice really was. Malthus for instance is quite willing to reference prostitution as one possible means to keep down population. He talks about “men,” and “a numerous class of females,” but he worries that those practices “lower in the most marked manner the dignity of human nature.” It degrades the female character and amongst “those unfortunate females with which all great towns abound, more real distress and aggravated misery are perhaps to be found, than in any other department of human life.”

How bad are those vices relative to starvation and population triage? Well, the modern world has debated that question and mostly we have opted for vice. You thus can see that the prosperity of the modern world does not refute Malthus. We faced the Malthusian dilemma and opted for one of his options, namely vice. It’s just that a lot of us don’t find those vices as morally abhorrent as Malthus did. You could say we invented another technology that (maybe) does not suffer from diminishing returns, namely improving the dignity and the living conditions those who practice vice. Contemporary college dorms seem pretty comfortable, and they have plenty of birth control, and of course lots of vice in the Malthusian sense. While those undergraduates might experience high rates of depression and also sexual violation, that life of vice still seems far better than life near the subsistence point. I am not sure what Malthus would think of college dorm sexual norms (and living standards!), but his broader failing was that he did not foresee the sanitization and partial moral neutering of what he considered to be vice.

Written by me, recommended, and open source at the above link.

A Genius Award for Airborne Transmission

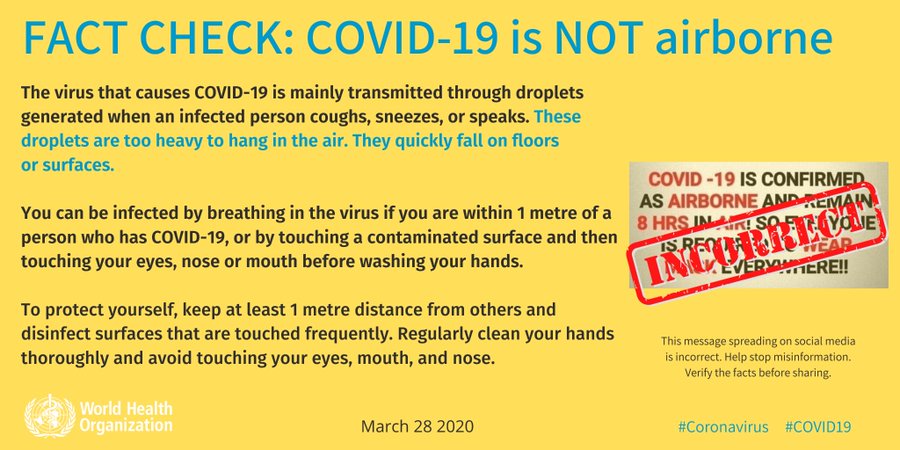

One of the strangest aspects of the pandemic was the early insistence by the WHO and the CDC that COVID was not airborne. “FACT: #COVID19 is NOT airborne.” the WHO tweeted on March 28, 2020, accompanied by a large graphic (at right). Even at that time, there was plenty of evidence that COVID was airborne. So why was the WHO so insistent that it wasn’t?

One of the strangest aspects of the pandemic was the early insistence by the WHO and the CDC that COVID was not airborne. “FACT: #COVID19 is NOT airborne.” the WHO tweeted on March 28, 2020, accompanied by a large graphic (at right). Even at that time, there was plenty of evidence that COVID was airborne. So why was the WHO so insistent that it wasn’t?

Ironically, some of the resistance to airborne transmission can be traced back to a significant achievement in epidemiology. Namely, John Snow’s groundbreaking arguments that cholera was spread through water and food, not bad air (miasma). Snow’s theory took time to be accepted but when the story of germ theory’s eventual triumph came to be told, the bad air proponents were painted as outdated and ignorant. This sentiment was so pervasive among physicians and health officials that anyone suggesting airborne transmission of disease was vaguely suspect and tainted. Hence, the WHOs and CDCs readiness to label airborne transmission as dangerous, unscientific “misinformation” promulgated on social media (see the graphic). In reality, of course, the two theories were not at odds as one could easily accept that some germs were airborne. Indeed, there were experts in the physics of aerosols who said just that but these experts were siloed in departments of physics and engineering and not in medicine, epidemiology and public health.

As a result of this siloing, we lost time and lives by telling people that they were fine if they kept to the 6ft “rule” and washed their hands, when what we should have been telling them was open the windows, clean the air with UVC, and get outside. Windows not windex.

Linsey Marr at Virginia Tech was one of the aerosol experts who took a prominent role in publicly opposing the WHO guidance and making the case for aerosol transmission (Jose-Luis Jimenez was another important example). Thus, it’s nice to see that Marr is among this year’s MacArthur “genius” award winners. A good interview with Marr is here.

It didn’t take a genius to understand airborne transmission but it took courage to put one’s reputation on the line and go against what seemed like the scientific consensus. Marr’s award is thus an award to a scientist for speaking publicly in a time of crisis. I hope it encourages others, both to speak up when necessary but also to listen.

Addendum: I didn’t take part in the aerosol debates but my wife, who has done research in aerosols and germs, told me early on that “of course COVID is airborne!” Wisely, I chose to take the word of my wife over that of the WHO and CDC.

Disputes over China and structural imbalances

There has been some pushback on my recent China consumption post, so let me review my initial points:

There exists a view, found most commonly in Michael Pettit (and also Matthew Klein), that suggests economies can have structural shortfalls of consumption in the long run and outside of liquidity traps.

My argument was that this view makes no sense, it is some mix of wrong and “not even wrong,” and it is not supported by a coherent model. If need be, relative prices will adjust to restore an equilibrium. If relative prices are prevented from adjusting, the actual problem is not best understood as a shortfall of consumption, and will not be fixed by a mere expansion of consumption.

Note that people who promote this view love the word “absorb,” and generally they are reluctant to talk much about relative price adjustments, or even why those price adjustments might not take place.

You will note Pettis claims Germany suffers from a similar problem, America too though of course the inverse version of it. So whatever observations you might make about China, the question remains whether this model makes sense more generally. (And Australia, which ran durable trade deficits from the 1970s to 2017, while putting in a strong performance, is a less popular topic.)

Pettis even has claimed that “US business investment is constrained by weak demand rather than costly capital”, and that is from April 4, 2023 (!).

It would take me a different blog post to explain how someone might arrive at such a point, with historic stops at Hobson, Foster, and Catchings along the way, but for now just realize we’re dealing with a very weird (and incorrect) theory here. I will note in passing that the afore-cited Pettis thread has other major problems, not to mention a vagueness about monetary policy responses, and that rather simply the main argument for current industrial policy is straightforward externalities, not convoluted claims about how foreign and domestic investment interact.

Pettis also implicates labor exploitation as a (the?) major factor behind trade surpluses, and furthermore he considers this to be a form of “protectionism.” Now you can play around with scholar.google.com, or ChatGPT, all you want, and you just won’t find this to be the dominant theory of trade surpluses or even close to that. As a claim, it is far stronger than what a complex literature will support, noting there is a general agreement that lower real wages (ceteris paribus) are one factor — among many — that can help exports. This point isn’t wrong as a matter of theory, it is simply a considerable overreach on empirical grounds. Of course, if Pettis has a piece showing statistically that a) there is a meaningful definition of labor exploitation here, and b) it is a much larger determinant of trade surpluses than the rest of the profession seems to think…I would gladly read and review it. Be very suspicious if you do not see such a link appear!

Another claim from Pettis that would not generate widespread agreement is: “…in an efficient, well-managed, and open trading system, large, persistent trade imbalances are rare and occur in only a very limited number of circumstances.” (see the above link) That is harder to test because arguably the initial conditions never are satisfied, but it does not represent the general point of view, which among other things, considers persistent differences in time preferences and productivities across nations.

Now, it does not save all of this mess to make a series of good, commonsense observations about China, as Patrick Chovanec has done (Say’s Law does hold in the medium-term, however). And as Brad Setser has done.

In fact, those threads (and their citation) make me all the more worried. There is not a general realization that the underlying theory does not make sense, and that the main claim about the determinants of trade surpluses is wrong, and that it requires a funny and under-argued tracing of virtually all trade imbalances to pathology. And to be clear, this is a theory that only a small minority of economists is putting forward. I am not the dissident here, rather I am the one delivering the bad news.

So the theory is wrong, and don’t let commonsense, correct observations about China throw you off the scent here.

Great News for Female Academics!

For decades female academics have been told that the deck is stacked against them by discrimination in hiring, funding, journal acceptances, recommendation letters and more. It’s dispiriting to be told that your career is not under your control and that, no matter what you do, you face an unfair, uphill battle. Why would any woman want to be a scientist when they are told things like this:

A vast literature….shows time after time, women in science are deemed to be inferior to men and are evaluated as less capable when performing similar or even identical work. This systemic devaluation of women women results in an array of real consequences: shorter, less praise-worth letters of recommendation, fewer research grants, awards and invitations to speak at conferences; and lower citation rates for their research…

The good news is that this depressing and dispiriting story isn’t true! In an extensive survey, meta-analysis, and new research, Ceci, Kahn and Williams show that the situation for women in academia is in many domains good to great. For example, in hiring for tenure the evidence is strong that women are advantaged. Moreover, women are advantaged especially in fields where they have relatively low representation (GEMP: geosciences, engineering, economics, mathematics/computer science, and physical science).

Among political scientists, Schröder et al. (2021) found that female political scientists had a 20% greater likelihood of obtaining a tenured position than comparably accomplished males in the same cohort after controlling for personal characteristics and accomplishments (publications, grants, children, etc.). Lutter and Schröder (2016) found that women needed 23% to 44% fewer publications than men to obtain a tenured job in German sociology departments.

…In summary, all of the seven administrative reports reveal substantial evidence that women applicants were at least as successful as and usually more successful than male applicants were—particularly in GEMP fields.

…In a natural experiment, French economists used national exam data for 11 fields, focusing on PhD holders who form the core of French academic hiring (Breda & Hillion, 2016). They compared blinded and nonblinded exam scores for the same men and women and discovered that women received higher scores when their gender was known than when it was not when a field was male dominant (math, physics, philosophy), indicating a positive bias, and that this difference strongly increased with a field’s male dominance. Specifically, women’s rank in male-dominated fields increased by up to 40% of a standard deviation. In contrast, male candidates in fields dominated by women (literature, foreign languages) were given a small boost over expectations based on blind ratings, but this difference was small and rarely significant.6

The situation is also very good in grant funding and journal acceptance rates which are either not biased or biased towards women. Similarly, “no persuasive evidence exists for the claim of antifemale bias in academic letters of recommendation.”

There is evidence of bias in student evaluations. Both female and male students rate male professors higher, even in situations where names are known but actual gender is blinded. Male students are more likely to write nasty comments. Most research universities, in my experience, don’t put much weight on student teaching evaluations, beyond do you pass a fairly low bar, but it can be disconcerting to get nasty comments.

There is also mild evidence of differences in salary, although less so when productivity is taken into account.

Some critics will say, but the real discrimination happens before a women applies for a tenure track job! Maybe so but that is a shifting of goal posts and we should take pride in the fact that in the United States today (and most developed countries) there is very little bias against women in high stakes, important decisions in tenure track hiring, journal acceptances, grant funding and so forth. This is a major accomplishment.

It should be noted that the Ceci, Kahn and Williams paper is an adversarial collaboration; Ceci and Williams have published previous work showing that women are, generally speaking, not discriminated against in academia while:

Kahn has a long history of revealing gender inequities in her field of economics, and her work runs counter to Ceci and Williams’s claims of gender fairness. Kahn was an early member of the American Economics Association’s Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession (CSWEP). Articles of hers in the American Economics Review (Kahn, 1993) and in the Journal of Economic Perspectives (Kahn, 1995) were the first publications on the status of women in the economics profession. She was the first to identify gender inequities as a concern in economics, something she has revisited every decade since then in her publications. In 2019, she co-organized a conference on women in economics, and her most recent analysis in 2021 found gender inequities persisting in tenure and promotion in economics (Ginther & Kahn, 2021). In short, gender bias in academia has been a long-standing passion of Kahn’s. Her findings diverge from Ceci and Williams’s, who have published a number of studies that have not found gender bias in the academy, such as their analyses of grants and tenure-track hiring in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS; Ceci & Williams, 2011; Williams & Ceci, 2015).

The Ceci, Kahn, and Williams paper covers much more material than I can cover here and is nuanced so read the whole thing but do also shout the good news from the rooftops!

That is from Mike in VA.