Results for “pollution” 197 found

Is “the better car experience” the next big tech breakthrough?

That is the question I raise in my new Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

Another reality of the contemporary automobile is that Tesla has managed to rethink the entire design. The dashboard and interior are reconfigured, the drive is electric, software is far more prominent and integrated into the design, voice recognition operates many systems, and there are self-driving features, too. Whether or not you think Tesla as a company will succeed, its design work has shown how much room there is for improvement.

You might object that cars have numerous negative features — but that’s where there is much of the potential for major transformation. Cars cause a lot of air pollution, but electric cars (or maybe even hydrogen cars) are on their way, and they will lower noise pollution too, as hybrids already do.

Cars also create traffic congestion, but congestion pricing can ease this problem significantly, as it already has in Singapore. Congestion pricing used to be seen as politically impossible, but the Washington area recently instituted it for one major highway during rush hour. The toll is allowed to rise as high as $40, but on most days it is possible to drive to work for about $10 and home for well under $10, at speeds of at least 50 mph. Manhattan also will move to congestion pricing, for south of 60th Street in Midtown, and the practice will probably spread, both within New York and elsewhere, partly because many municipalities are strapped for cash. As for building new highways, transportation analyst Robert W. Poole Jr. argues in his new book that there is plenty of room for the private-sector toll concession model to grow, leading to more roads and easier commutes.

In other words, the two biggest problems with cars — pollution and traffic congestion — have gone from “impossible to solve” to the verge of manageability.

There is much more at the link, and here is the closer:

Right now there are about 281 million cars registered in the U.S., and they have pretty hefty price tags and demand many hours of time. The basic infrastructures and legal frameworks are already in place. So, despite the current obsessions with robots and gene editing, it should be evident that the biggest tangible changes from technology in the next 20 years are likely to come in a relatively mundane area of life — namely, life on the road.

What I’ve been reading

1. Aladdin, a new translation by Yasmine Seale. A wonderful, lively small volume, a good reintroduction to the Arabian Nights, recommended.

2. Shalini Shankar, Beeline: What Spelling Bees Reveal About Generation Z’s New Path to Success. Not as analytical as I was wanting, but more analytical than I had been expecting.

3. Rowan Ricardo Phillips, The Circuit: A Tennis Odyssey. Provides a good look at the interior world of tennis competition, with emphasis on very recent times. A good look at how to think about the game, not only in the abstract, but as it plays out through the logic of particular events and tournaments.

4. Tim Smedley, Clearing the Air: The Beginning and the End of Air Pollution. Perhaps the best extant introduction to the air pollution issue, one of the world’s most important and underrated crises, and no I am not talking about carbon.

5. Gordon Peake, Beloved Land: Stories, Struggles, and Secrets from Timor-Leste. Mostly analytical, with real information blended with travelogue. I can’t judge the content, but I was never tempted to put this one down and throw it away.

6. Roderick Beaton, Greece: Biography of a Modern Nation. Excellent survey and overview, makes the late 19th century intelligible, among other achievements. “For Greeks, unlike the concept of the nation, the state had always been an object of popular derision.”

World Bank affiliate is not shielded from all legal action

The new Supreme Court ruling seems to me bigger news than the play it is receiving:

International organizations based in the United States are not completely shielded from legal liability in American courts, the Supreme Court ruled Wednesday.

The 7-to-1 ruling directly involves an arm of the World Bank, which provides loans for projects in poor and developing countries. The decision could have implications for other similar organizations involved in financing overseas development.

The case centers on the Washington-based International Finance Corp., which provided a $450 million loan for the construction of a coal-fired power plant in the state of Gujarat in western India. Farmers, fishermen and a small village went to federal court in 2015 over alleged air pollution and water contamination from the plant.

Here is the full story by Ann E. Marimow. Once this door is open…And you also can consider this another move back toward nationalist organization of responsibility.

How to travel to India

From a reader:

I have really enjoyed your travel posts on various countries, and am currently planning a trip to India for the month of November. However, I have struggled to find much writing of yours on the country. Perhaps a post on tips/places/cities/culture is in order? It would be much appreciated.

I have only a few India tips, but I can recommend them very, very strongly. Here goes:

1. You can’t just walk around all day and deal with the pollution, the bad sidewalks, and dodging the traffic. This ain’t Paris. Plan accordingly.

2. When Alex set off to live in India, I said to him: “Alex, after a few weeks there, I want you to email me “the number.” The number is how many consecutive hours you can circulate in an Indian city without having to stop and resort to a comfortable version of the indoors.” You too will figure out pretty quickly what your number is, and it won’t take you a few weeks.

3. India is one of the very best and most memorable trips you can take. You should go repeatedly.

4. Every single part of India is interesting and worth visiting, as far as I can tell after five trips. That said, I find Bangalore quite over-visited relative to its level of interest.

5. My favorite places in India are Mumbai, Chennai, Rajasthan, and Kolkaata. Still, I could imagine a rational person with interests broadly similar to my own having a quite different list.

6. India has the best food in the world. It is not only permissible but indeed recommended to take all of your meals in fancy hotel restaurants. Do not eat the street food in India (and I eat it virtually everywhere else). It is also permissible to find two or three very good hotel restaurants — or even one — and simply run through their menus. You won’t be disappointed.

7. Invest in a very, very good hotel. It is affordable, and you will need it, and it will be a special memory all its own.

8. Being driven around in the Indian countryside is terrifying (and I have low standards here, I do this all the time in other non-rich countries). If it were safer, I would see many more parts of India. But it isn’t. So I don’t.

9. If you go during monsoon season, your trip will be quite memorable. I cannot say I recommend this (I don’t), but I am myself glad I did it once, in Goa, when monsoon season started early. I got a lot of work done.

10. Do not expect punctuality.

11. Most of the sights in India, including the very famous ones, are overrated. The main sight is India itself, and that is underrated.

12. “In religion, every Indian is a millionaire.”

I thank Yana and Dan Wang and Alex for discussions relevant to this post.

Buy (or Rent) Coal! The Coasean Climate Change Policy

Since climate change and what to do about it are in the news it’s time to re-up an underrated idea, buy coal! Carbon taxes increase the price of carbon and induce economic and technological substitution towards lower-carbon sources of fuel in the countries that adopt them. As carbon-tax countries reduce fuel use, however, non carbon-tax countries see the price of their fuel decline. Thus, unless all countries join the tax-coalition, there is leakage. Supply-side policies are an alternative to demand supply policies. The United States, for example, could buy out and close coal mines, including giving the workers substantial retirement/reallocation bonuses, thus reducing the world supply of coal which is still the largest source of C02 emissions.

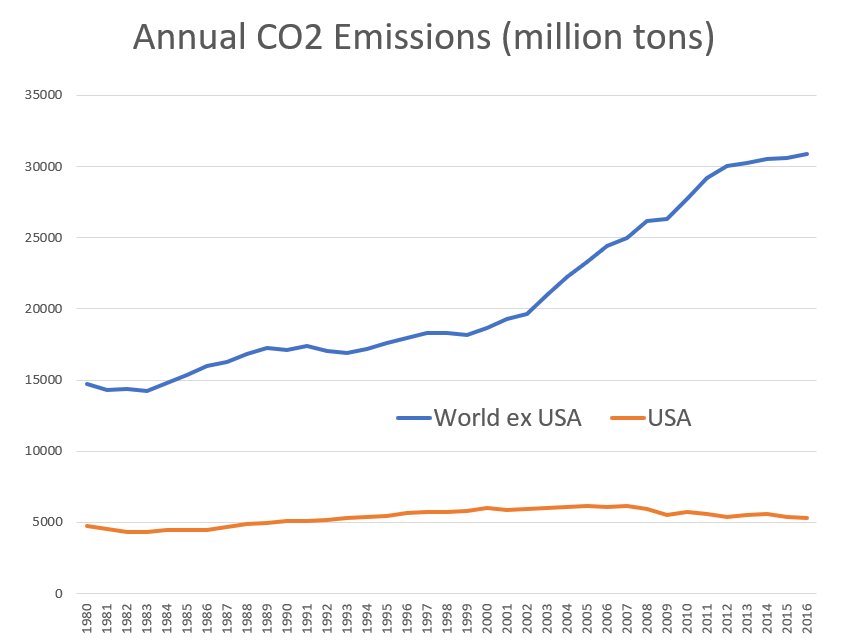

You can get rich by hitting an oil gusher, but coal is relatively expensive to mine and to transport. Thus, it’s relatively cheap to buy out coal mines because you aren’t buying the coal, you’re buying the right to leave the coal in the ground. Cutting the supply of coal raises its price which will increase the quantity supplied in other countries. Thus, there is the potential for supply leakage as well as demand leakage. It’s probably easier to use more coal when the price of coal falls (electricity, for example, can be generated in a variety of ways) than it is to mine more coal when the price rises. In other words, the elasticity of the demand for coal is greater than the elasticity of supply so supply leakage is probably less than demand leakage. Furthermore, supply leakage can be handled by buying out supply in the non-coalition countries. As Noah Smith pointed out with the graph at right (data) US CO2 emissions are actually falling while the rest of the world keeps rising (as they catch up in per-capita terms) so addressing the CO2 emissions problem requires bringing countries like China and India on board.

Coal use in China is very high and increasing. India has been canceling coal plants as solar becomes cheaper but coal is still by far the largest source of power in India. Thus, there is plenty of opportunity to buy out, high-cost coal mines in China and India.

It might seem odd to buy Chinese and Indian coal mines but we buy Chinese and Indian labor, why not a coal mine? Moreover, it’s important to understand that the policy is to buy only up to the point that it benefits both parties. Buying coal isn’t foreign aid, it’s a pollution reduction plan just like a carbon tax or R&D investment and because we can buy barely-profitable coal mines and avoid the problem of leakage this is a low-cost method to reduce CO2 emissions.

Collier and Venables worry that foreign voters won’t like foreign investors buying up coal mines, although foreign investment is hardly uncommon and foreigners do protect rainforests by buying the right to cut them down. In any case, Collier and Venables suggest a cap-extract and trade program. Under cap-extract there is a cap on global extractions of carbon (not use) but rights to extract can be traded. Since it’s more valuable to extract say oil than coal what this would mean is that payments would flow from mostly developed countries to developing countries which makes it clear that we are all in the boat together.

Even without a cap-extract and trade program, however, there are other factors that make buying coal attractive to people in selling countries, namely coal is killing them even putting aside the dangers of climate change.

NYTimes: Burning coal has the worst health impact of any source of air pollution in China and caused 366,000 premature deaths in 2013, Chinese and American researchers said on Thursday.

Coal is responsible for about 40 percent of the deadly fine particulate matter known as PM 2.5 in China’s atmosphere, according to a study the researchers released in Beijing.

India’s air quality is even worse than China’s and is responsible for some 1.2 million early deaths annually. A 25% cut in pollution in India could increase life-expectancy by 1.3 years and in some highly polluted cities such as Delhi by 2.8 years. Not all pollution comes from coal but a substantial amount does.

Buyers might worry that a foreign government will take their money and later renege on the deal. There are lots of ways to deal with this problem–turn the coal fields into a national park, for example, or develop them for housing. But let’s turn a problem into a solution. Instead of buying coal, we could rent it. In other words, buy the right to delay mining the coal for say 10 years. Given the rate of improvement in solar, many coal plants will be uneconomic in 10 years and given the rate of improvement in living standards and the consequent increased demand for clean air, many coal plants in India and China could well be unpolitical in 10 years. Thus, it is true that some solutions are naturally in the offing, but for exactly this reason some coal plants are going to be working extra hours in the next decade to squeeze out what profit they can while they still can. We can avoid this last push of CO2 into the atmosphere by buying up the right to extract and holding it for a decade.

A program to leave coal in the ground could easily pay for itself in lives saved and climate stabilized.

Wednesday assorted links

They solved for the equilibrium, China equilibrium of the day

China will be less severe with its smog curbs this winter as it grapples with slower economic growth and a trade war with the United States, according to a government plan released on Thursday.

Instead of imposing blanket bans on industrial production in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei area as it did last winter, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment said it would let steel plants continue production as long as their emissions met standards.

Targets for overall emissions cuts have also been revised down. In the next six months, 28 cities in northern China are required to cut levels of PM2.5 – the tiny airborne particles that are most harmful to human health – by about 3 per cent from a year ago.

That is less than the 5 per cent cut proposed in an initial plan seen by the South China Morning Post last month.

Meanwhile, the new plan stipulates that the number of days of severe air pollution should be reduced by about 3 per cent, also revised down from 5 per cent in last month’s draft.

Here is more from Orange Wang at SCMP. As I am sure you all know, air pollution (and I don’t just mean carbon emissions) is one of the great underrated problems in the world today. The trade war with China is making it worse.

What is land for Georgist purposes?

Matthew Prewitt wrote this interesting piece “Reimagining Property: A Philosophical Look at Harberger Taxation.” As he defines a Harberger tax, you report the value of your property, pay a tax on that amount, but if you under-report the value someone can buy the property from you at that price. The goal is to encourage turnover of assets, rather than hoarding of assets. Prewitt writes:

Recall that in a world where the natural and artificial components of capital were magically unmixed, we might impose a Harberger tax near the turnover rate on natural capital, and a Harberger tax near zero on artificial capital. But, recognizing that we do not live in such an ideal world, Posner and Weyl propose to set HT rates at varying percentages of the turnover rate for different assets, depending on those assets’ investment elasticities. That is, assets whose value increases more readily with investment should generally enjoy lower HT relative to their turnover rate, to facilitate investment.

…artificial capital is value that emerges in response to incentives…

As time passes, artificial capital starts to resemble natural capital.

Think of a new boat, built yesterday. Now think of the Parthenon. The labor that made the boat can and should be rewarded. It makes sense for the spoils of boat ownership to accrue to its builder. But the labor that made the Parthenon has dissolved into the mists of time. There is no sense rewarding it. We simply find the building in our environment, like an ocean, a mountain, or a nickel deposit. Whoever possess it deserves an incentive for its upkeep, but not a reward for its existence. Any profits from Parthenon ownership ought to be distributed broadly, and not end up in any particular pocket. Thus, unlike the new boat, the Parthenon ought to be treated like natural capital. Yet it is the product of human labor; when erected, it was the very epitome of artificial capital.

Of course there is a decay function in how we treat rights in intellectual property, and this argument suggests there should be a decay function for rights in physical capital as well. After some point in time, that physical capital becomes Georgist land, and thus subject to the efficiencies of the land tax, not to mention possible Harberger taxation.

Prewitt’s conclusion is:

- artificial capital should have a Harberger tax rate near zero

- natural capital should have a Harberger tax near the turnover rate

- artificial capital becomes more like natural capital as more time passes and/or it changes hands more times

More generally, as I suggested about five years ago, the forthcoming fights will be about the taxation of wealth not income.

I wonder, however, if this one shouldn’t be argued in the opposite direction. Let’s say excellence is under-rewarded. If a structure or capital expenditure lasts for a long period of time, maybe that is strongly positive selection and it deserves a subsidy? For one thing, such structures are likely to be iconic brands of a kind, with strong option value and the costs of irreversibility if we let them perish or fall into disrepair. The example of the Parthenon is a useful one, because in fact the monument is endangered by air pollution, and arguably it should receive a larger subsidy for protection, whether for intrinsic reasons or for its economic contribution to Greek tourism.

For the pointer I thank David S.

Sunday assorted links

Which cities have people-watching street cafes?

D. asks me that question, citing Morocco, BA, and Paris. Here are a few factors militating in favor of such cafes:

1. The weather should be reasonable. This militates in favor of Mediterranean climates, with Paris eking through nonetheless. It hurts much of Asia.

2. The broad highways and thoroughfares should be removed from where the cafes might go. This factor harms Los Angeles, which otherwise has excellent weather, and helps La Jolla. Note that BA and some of the larger Moroccan cities were designed and built up around the same time, based on broadly European models, and to fit early 20th century technologies.

3. Street crime must be acceptably low. Bye bye Brazil.

4. Pollution should be fairly low, otherwise sitting outside is unpleasant. This harm many Indian and Chinese cities.

5. Streets must not be too steep. Sorry La Paz, and yes here at MR we adjust steepness coefficients by altitude.

6. Skyscrapers must not be too plentiful. This harms Manhattan, because the sunlight is mostly blocked.

7. Explicit or implicit marginal tax rates on labor should be relatively high. Another boost for the Mediterranean. And is cafe culture therefore correlated with smoking culture?

7b. Explicit or implicit land rents should be “low enough.” After all, they have to be willing to let you sit there all day. Just try that in midtown Manhattan.

8. The cities should have mixed-use neighborhoods, well-connected to each other by foot, conducive to many diverse groups of people walking through. This hurts many parts of the United States and also some parts of Latin America. It is a big gain for Paris.

9. The city dwellers need some tradition of “being alone,” so that these individuals use the cafe to connect to the outside. You will note that in many parts of Italy, the people-watching street cafe is outcompeted by the “stationary street conference, five guys who know each other really well yelling at each other about who knows what?” They never get around to that cafe chair. So the city needs some degree of anonymity, but not too much. This harms some of the more traditional societies found around the Mediterranean. On the other side of the distribution, too strong a tradition of television-watching hurts cafe life too.

10. Another competitor to the people-watching street cafe is the zócalo town square tradition of Mexico. I myself prefer the centralization of the zócalo (though admittedly it does not scale well fractally). So the city also has to fail in providing just the right kind of parks and park benches and focality in its very center. Surprise, surprise, but dysfunctional local public goods are by no means unheard of around the Mediterranean, Paris too, BA, and cities such as Casablanca.

What else?

Why is there no lead-homicide connection in Eastern Europe?

Saturday assorted links

My Conversation with Charles C. Mann

Here is the audio and transcript, Charles was in superb form. We talked about air pollution (carbon and otherwise), environmental pessimism, whether millions will ever starve and are there ultimate limits to growth, how the Spaniards took over the Aztecs, where is the best food in Mexico, whether hunter-gatherer society is overrated, Jackie Chan, topsoil, Emily Dickinson, James C. Scott, the most underrated trip in the Americas, Zardoz, and much much more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: But if you had to pick a leading candidate to be the fixed factor, I’m not saying you have to endorse it, but what’s the most likely fixed factor if there is one?

MANN: Well, water is certainly a big candidate. There just really isn’t that much fresh water.

COWEN: But we can price it more, and since we have growing wealth — global economy grows at 4 percent a year — we can subsidize those who need subsidies…

MANN: You’re right. But water’s obviously one of them. But hovering over it is these questions about whether these natural cycles . . . is kind of a fundamental question about life itself. Is an ecosystem an actual system with an integrity of its own, with rules of its own that you violate at your peril? Which is the fundamental premise of the environmental movement. Or is an ecosystem more like an apartment building in which it is just a bunch of people who happen to live in the same space and share a few common necessities?

I don’t think ecology really has settled on this. There’s a guy in Florida, Dan Simberloff, who is a wonderful ecologist who has kind of made a career out of destroying all these models, these elegant models, one after another. So that’s the fundamental guess.

If it turns out that it’s just a collection of factors that we can shift around, that nature’s purely instrumental and we can do with it what we want, then we have a lot more breathing room. If it turns out that there really are these overarching cycles, which seems to be the intuition of the ecologists who study this, then we have less room than we think.

And:

COWEN: Jared Diamond.

MANN: I think an interesting guy who really should learn more about social sciences.

COWEN: Economics in particular.

MANN: Yes.

COWEN: Theory of common property resources.

MANN: Yeah.

And finally:

MANN: …What I think is the underrated factor is that Cortez was much less a military genius than he was a political genius. He was quite a remarkable politician, really deft. And what he did is . . . The Aztecs were an empire, the Triple Alliance, and they were not nice people. They were rough customers. And there was a lot of people whom they had subjugated, and people whom they were warring on who really detested them. And Cortez was able to knit them together into an enormous army, lead that army in there, have all these people do all that, and then hijack the result. This is an act of political genius worthy of Napoleon.

Self-recommending, and I am delighted to again express my enthusiasm for Charles’s new The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow’s World. Here is Bill Easterly’s enthusiastic WSJ review of the book.

Benjamin Zycher on solar power

From my email, if you would like to read a more negative than usual take:

“A couple of observations on your Bloomberg column on solar power:

- There is nothing “clean” about solar (or wind) electricity, primarily because of its intermittent nature. Because it is unreliable, it cannot be scheduled (it is not dispatchable), and so must be backed up with conventional (usually gas, sometimes coal) plants. The latter units must be cycled up and down depending on whether the sun is shining or not, which means that they must be operated inefficiently (they experience rising heat rates), increasing their emissions of conventional effluents and greenhouse gases. Engineering studies for Colorado and Texas, for example, estimate that this adverse effect becomes important when the market share in terms of capacity reaches around 10 percent (combined with the guaranteed market shares and must-take regulations enforced by many states). I have been beating on this drum for years, but the press and many others continue to describe solar and wind power as “clean.” No, it is not.

- That emissions pattern is separate from the problem of solar panel disposal, vastly underpublicized in my view, in a world in which solid-waste disposal is priced inefficiently.

- The Independent System Operators generally are forced to take renewable power when it is available, and the PUCs are forced to roll their high costs into the rate bases, spreading the costs across all consumers. (The same is true for the high transmission costs attendant upon renewables.) There has been some reform around the margins in a few states, as the PUCs have trimmed the net metering subsidies for rooftop solar systems, but this is a minor adjustment in a system characterized by vast inefficiency, cronyism and interest-group rent-seeking, upward transfers of income, feathering of bureaucratic nests, and increased pollution. Such are the fruits of government wisdom.”

Were U.S. nuclear tests more harmful than we had thought?

So says Keith A. Meyers, job candidate from University of Arizona. I found this to be a startling result, taken from his secondary paper:

During the Cold War the United States detonated hundreds of atomic weapons at the Nevada Test Site. Many of these nuclear tests were conducted above ground and released tremendous amounts of radioactive pollution into the environment. This paper combines a novel dataset measuring annual county level fallout patterns for the continental U.S. with vital statistics records. I find that fallout from nuclear testing led to persistent and substantial increases in overall mortality for large portions of the country. The cumulative number of excess deaths attributable to these tests is comparable to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Basically he combines mortality estimates with measures of Iodine-131 concentrations in locally produced milk, “to provide a more precise estimate of human exposure to fallout than previous studies.” The most significant effects are in the Great Plains and Central Northwest of America, and “Back-of-the-envelope estimates suggest that fallout from nuclear testing contributed between 340,000 to 460,000 excess deaths from 1951 to 1973.”

His primary job market paper is on damage to agriculture from nuclear testing.

That is from commentator Aurel at SSC.