Results for “pollution” 206 found

Reducing Pollution in India with a Cap and Trade Market

India has some of the worst air pollution in the world. India regulates pollution but it uses a command and control approach with criminal penalties, a system in tension with enforcement given low-state capacity. The result has been widespread corruption, inefficiency, and poor enforcement of pollution controls. In a very important paper, Greenstone, Pande, Ryan and Sudarshan report on an experiment with a market for particulate matter in Surat, India. In fact, this is the first particulate-matter market anywhere in the world.

The experiment created two sets of firms, the treatment set were required to install continuous emission monitoring systems (CEMS) which measured the output of particulate matter. The control set of firms remained under the command and control system which required the installation of various pollution control devices and spot checks. Firms were randomly assigned to treatment or control. Pollution at treatment firms was capped and permits were issued for 80% of the cap so firms could pollute at 80% of the cap for free. Permits for the remaining 20% of the cap were sold at auction and trading was allowed. Treatment plants which polluted more than their permits allowed paid substantial fines, about double the cost they would have paid to buy the necessary permits.

The one and half year experiment revealed a great deal of importance. First, the CEMS systems and the switch to financial penalties reduced the cost of enforcement so that essentially all firms quickly came into compliance. Second, trading was vigorous, which indicated that firms have heterogeneous and changing costs. Moreover, by allowing for a more information rich market the costs of achieving a given level of pollution fell. Pollution costs were 11% lower in treatment firms compared to control firms at the same level of pollution. The value of trade in lowering abatement costs illustrates Hayek’s idea that one of the virtues of markets is that they make use of information of particular circumstances of time and place. In fact, since the costs of achieving a given level of pollution were low, the authorities decreased the cap so that the treatment firms reduced their pollution levels significantly relative to the control firms.

The CEMS systems were a fixed cost but because abatement costs decreased, the overall expense was reasonable. The need for monitoring systems and procedures highlights Coase’s insight that property rights in externalities must be designed and enforced, the visible and invisible hand work best together.

Using estimates on a statistical life-year in India of $9,500 (about 1/10th to 1/30 the level typically used in the US) the authors find that the benefits of substantial pollution reduction exceed the costs by a factor of 25:1 or higher.

I have emphasized (and video here) that there are significant productivity gains to reducing air pollution which would make these benefit to cost ratios even higher. Less pollution can mean more health and more wealth.

The authors are especially to be congratulated because this paper began in 2010 with discussions with the Gujurat Pollution Control Board. It took over a decade to implement the experiment with the authors helping to design not just the market but also the technical standards for CEMS monitoring. Amazing. The success of the system is already leading to expansion across India. Bravo!

Hat tip: Paul Novosad.

The Unseen Fallout: Chernobyl’s Deadly Air Pollution Legacy

A fascinating new paper The Political Economic Determinants of Nuclear Power: Evidence from Chernobyl by Makarin, Qian, and Wang was recently presented at the NBER Pol. Economy conference. The paper is nominally about how fossil fuel companies and coal miners in the US and UK used the Chernobyl disaster to successfully lobby against building more nuclear power plants. The data collection here is impressive but that is just how democracy works. I found the political economy section less interesting than some of the background material.

First, the Chernobyl disaster ended nuclear power plant (NPP) construction in the United States (top-left panel), the country with the most NPPs in the world . Surprisingly, the Three Mile Island accident in 1979 (much less serious than Chernobyl) had very little effect on construction; albeit the 1-2 punch with Chernobyl in 1986 surely didn’t help. The same pattern is very clear across all countries and also all democracies (top-right panel). The bottom two panels show the same data but looking at new plants rather than the cumulative total–there was a sharp break in 1986 with growth quickly converging to zero new plants per year.

Fewer nuclear plants than otherwise would have been the case might have made a disaster less likely but there were countervailing forces:

We document that the decline in new NPPs in democracies after Chernobyl was accompanied by an increase in the average age of the NPPs in use. To satisfy the rise in energy demand, reactors built prior to Chernobyl continued operating past their initially scheduled retirement dates. Using data on NPP incident reports, we show that such plants are more likely to have accidents. The data imply that Chernobyl resulted in the continued operation of older and more dangerous NPPs in the democracies.

Moreover, safety declined because the existing plants got older but in addition “the slowdown of new NPP construction…delayed the adoption of new safer plants.” This is a point about innovation that I have often emphasized (see also here)

The key to innovation is continuous refinement and improvement…. Learning by doing requires doing….Thus, when considering innovation today, it’s essential to think about not only the current state of technology but also about the entire trajectory of development. A treatment that’s marginally better today may be much better tomorrow.

Regulation increased costs substantially:

The U.S. NRC requires six-to-seven-years to approve NPPs. The total construction time afterwards ranges from decades to indefinite. Cost overruns and changing regulatory requirements during the construction process sometime forces construction to be abandoned after significant sunk costs have been made. This often leads investors to abandon construction after already sunk billions of dollars of investment. Worldwide, companies have stopped construction on 90 reactors since the 1980s. 40 of those were in the U.S. alone. For example, in 2017, two South Carolina utilities abandoned two unfinished Westinghouse AP1000 reactors due to significant construction delays and cost overruns. At the time, this left two other U.S. AP1000 reactors under construction in Georgia. The original cost estimate of $14 billion for these two reactors rose to $23 billion. Construction only continued when the U.S. federal government promised financial support. These were the first new reactors in the U.S. in decades. In contrast, recent NPPs in China have taken only four to six years and $2 billion dollars per reactor. When considering the choice of investing in nuclear energy versus fossil fuel energy, note that a typical natural gas plant takes approximately two years to construct (Lovering et al., 2016).

Chernobyl, to be clear, was a very costly disaster

The initial emergency response, together with later decontamination of the environment, required more than 500,000 personnel and an estimated US$68 billion (2019 USD). Between five and seven percent of government spending in Ukraine is still related to Chernobyl. (emphasis added, AT) In Belarus, Chernobyl-related expenses fell from twenty-two percent of the national budget in 1991 to six percent by 2002.

The biggest safety effect of the decline in nuclear power plants was the increase in air pollution. The authors use satellite date on ambient particles to show that when a new nuclear plant comes online pollution in nearby cities declines significantly. Second, they use the decline in pollution to create preliminary estimates of the effect of pollution on health:

According to our calculations, the construction of an additional NPP, by reducing the total suspended particles (TSP) in the ambient environment, could on average save 816,058 additional life years.

According to our baseline estimates (Table 1), over the past 38 years, Chernobyl reduced the total number of NPPs worldwide by 389, which is almost entirely driven by the slowdown of new construction in democracies. Our calculations thus suggest that, globally, more than 318 million expected life years have been lost in democratic countries due to the decline in NPP growth in these countries after Chernobyl.

The authors use the Air Quality Life Index from the University of Chicago which I think is on the high side of estimates. Nevertheless, as you know, I think the new air pollution literature is credible (also here) so I think the bottom line is almost certainly correct. Namely, Chernobyl caused many more deaths by reducing nuclear power plant construction and increasing air pollution than by its direct effects which were small albeit not negligible.

The Birth-Weight Pollution Paradox

Maxim Massenkoff asks a very good question. If pollution reduces birth weight as much as the micro studies on pollution suggest, why aren’t birth weights very low in very polluted cities and countries? Figure 1, for example, shows birth weights in a variety of highly polluted world cities. The yellow dashed and blue lines show “predicted” birth weights extrapolated from the well-known Alexander and Schwandt “Volkswagen study” which looked at the effects of increased pollution in the United States. Despite the fact that every one of the highly-polluted cities is much more polluted than the most polluted US city, birth weight is not tremendously lower in these cities. Indeed, there is no obvious correlation between birth weight and pollution at all.

Similarly, US cities were more polluted in the past but were birth weights lower in the past? Figure 2 shows a number of US cities which were two to three times more polluted in 1972 (right side of diagram) than 2002 (left side of diagram). Yet, birth weights do not appear lower in the more polluted past and certainly do not follow the extrapolated birth weight-pollution predictions from the micro literature.

Similarly, US cities were more polluted in the past but were birth weights lower in the past? Figure 2 shows a number of US cities which were two to three times more polluted in 1972 (right side of diagram) than 2002 (left side of diagram). Yet, birth weights do not appear lower in the more polluted past and certainly do not follow the extrapolated birth weight-pollution predictions from the micro literature.

Massenkoff looks at a variety of possible explanations. One possibility, for example, is culling. Perhaps in highly polluted areas there are more miscarriages, still births or difficulty conceiving with the result that the observed sample of births is highly selected. There is some evidence that pollution increases miscarriages and stillbirths but these tend to be correlated with lower birth weight–a scarring effect rather than a culling effect. In addition, the effect of pollution on miscarriages and stillbirths also appears to be bigger on a micro level than on a macro level. That is, these rates aren’t massively higher in high pollution countries.

Another possibility is that pollution isn’t that bad and, in particular, not as bad as I have suggested. As a good Bayesian, I update, but for reasons I have given here, it’s not justifiable to update very much.

I assume, as I always do, that there are some overestimates in the micro literature for the usual reasons. But, more fundamentally, my best guess for the birth-weight pollution paradox is that weight is one of the easiest margins on which the body can adapt and compensate. Even in poor countries there are plenty of calories to go around and so it’s relatively easy for the body to adjust to higher pollution, on this margin. Indeed, weight is known as a variable that creates paradoxes!

Micro studies on weight and exercise, for example, show that exercise reduces weight. But looking across countries, societies, and time we don’t see big effects–indeed, calorie expenditure doesn’t vary much with exercise! Importantly, notice that the micro-estimates are correct. If you increase physical activity for the next 3 months, holding all else equal (which is possible for 3 months), you will lose weight. However, the micro estimates are difficult to extrapolate to permanent, long-run changes because there are complex, adaptive mechanisms governing weight, calorie consumption and energy expenditure.

The exercise paradox doesn’t mean that exercise isn’t good for you–the evidence on the benefits of exercise is extensive and credible. In the same way the birth-weight pollution paradox doesn’t mean that pollution isn’t harmful–the evidence on the costs of pollution is extensive and credible. In particular, it’s going to be much harder to adapt to pollution for heart disease, cancer, life expectancy and IQ than for weight.

I am always impressed with papers that present big, obviously-true facts that most people have simply missed. Massenkoff is becoming a leader in this field.

Air Pollution Redux

New York City today has the worst air quality in the world, so now seems like a good time for a quick redux on air pollution. Essentially, everything we have learned in the last couple of decades points to the conclusion that air pollution is worse than we thought. Air pollution increases cancer and heart disease and those are just the more obvious effects. We now also now know that it reduces IQ and impedes physical and cognitive performance on a wide variety of tasks. Air pollution is especially bad for infants, who may have life-long impacts as well as the young and the elderly. I’m not especially worried about the wildfires but the orange skies ought to make the costs of pollution more salient. As Tyler noted, one reason air pollution doesn’t get the attention that it deserves is that it’s invisible and the costs are cumulative:

Air pollution causes many deaths. But it is rare to see or read about a person dying directly from air pollution. Lung cancer and cardiac disease are frequently cited as causes of death, even though they may stem from air pollution.

That’s the bad news. The good news, hidden inside the bad news, is that the costs of air pollution on productivity are so high that there are plausible ways of reducing some air pollution and increasing health and wealth, especially in high pollution countries but likely also in the United States with well-targeted policies.

For evidence on the above, you can see some of the posts below. Tyler and I have been posting about air pollution for a long time. Tyler first said air pollution was an underrated problem in 2005 and it was still underrated in 2021!

- Why the New Pollution Literature is Credible

- Air Pollution Reduces IQ, A Lot

- Air Pollution Kills

- David Wallace-Wells with a good overview.

- A good overview of the non-health impacts of pollution.

Shruti on Effective Altruism, malaria, India, and air pollution

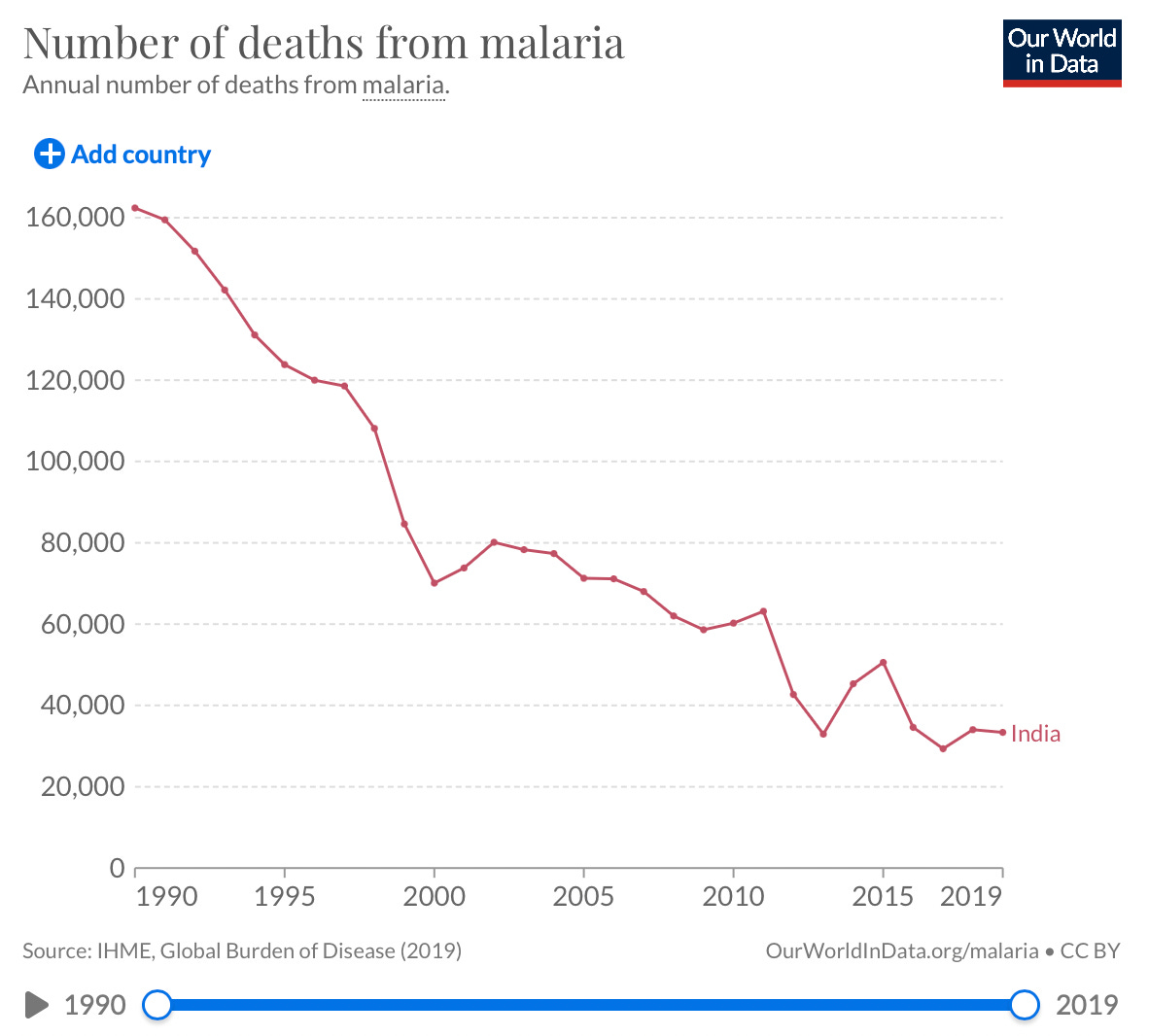

Look at the decline in malaria deaths in India since the big bang reforms in 1991, which placed India on a higher growth trajectory averaging about 6 percent annual growth for almost three decades. Malaria deaths declined because Indians could afford better sanitation preventing illness and greater access to healthcare in case they contracted malaria. India did not witness a sudden surge in producing, importing or distributing mosquito nets. I grew up in India, in an area that is even today hit by dengue during the monsoon, but I have never seen the shortage of mosquito nets driving the surge in dengue patients. On the contrary, a surge in cases is caused by the municipal government allowing water logging and not maintaining appropriate levels of public sanitation. Or because of overcrowded hospitals that cannot save the lives of dengue patients in time.

There is much more at the link, from Shruti’s new Substack.

Pollution and Macro Inequality

Combining 36 years of satellite derived PM2.5 concentrations with individual-level administrative data provided by the U.S. Census Bureau and Internal Revenue Service (IRS), we provide new evidence on the important role that disparities in air pollution exposure play in shaping broader patterns of economic opportunity and inequality in the United States. We first document that early-life exposure to particulate matter is one of the top five predictors of upward mobility in the United States. Second, we exploit regulation-induced reductions in pollution exposure from the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments to produce new age-specific estimates of pollution-earnings relationship. Combined with individual-level measures of pollution exposure during early childhood, we calculate that disparities in air pollution can account for 17-26 percent of the Black-White earnings gap, 5-27 percent of the Hispanic-White earnings gap, and 6-20 percent of the average neighborhood-earnings effect (Chetty and Hendren, 2018; Chetty, Hendren, and Katz, 2016). Collectively, our findings indicate that environmental inequality is an important contributor to observed patterns of racial economic disparities, income inequality and economic opportunity in the United States.

That’s Colmer, Voorheis and Williams summarizing Air Pollution and Economic Opportunity in the United States. The authors also estimate that

…a 1 μg/m3reduction in prenatal PM2.5 exposure is associated with a $1,105 increase in later-life W-2 earnings and…a 1 μg/m3 reduction in prenatal PM2.5 exposure is associated with a 1.29 percentile rank point increase in upward mobility…We estimate pollution-earnings relationships for each age of exposure from birth to age 12 and show that the relationship between pollution exposure and earnings is stable up to age 4 and then diminishes quickly. We do not estimate a meaningful relationship between particulate matter exposure and later-life earnings from age 8 onward.

These estimate are big but given the substantial number of micro-estimates of the effect of pollution on IQ and cognition that Tyler and I have discussed before (see also this video) substantial effects at the macro level are almost inevitable.

Driving Buy: Pollution, Customers and Development

The literature on air pollution continues to grow. In an impressive paper, Bassi et al. show that firms in Uganda locate on busy roads, Busy roads are more polluted but there are more customers driving and they rely on direct customer acquisition, rather than advertising or marketing, to get customers.

Location choice thus entails a trade-off between pollution exposure, which we verify to be mainly driven by road traffic, and access to customers. We also use our survey data to argue that the benefits can be explained primarily by the fact that, as it is typically the case across the developing world, firms sell locally through face-to-face interactions and do not have any other means to access customers than to be as visible as possible to them. Therefore, proximity to busy roads is essential.

Locating along busy roads increases profits per worker but reduces life expectancy of workers by about two months. A two month loss in life expectancy is substantial. Uganda is so poor (GDP per-capita ~$720), however, that the authors find that an (imaginary) policy of randomly allocating firms would not be cost-effective. Randomly allocating firms, however, is only one potential policy–others include using more buses or instituting a congestion tax. India has higher per capita GDP than Uganda so if all else were equal many such policies would pay in India. One type of “firm” that I have seen locate on congested roads in India is beggars and street sellers. It’s obvious that they go where the customers are but at the price of locating in very polluted areas.

I argued in India recently that reduced pollution could increase GDP. I continue to think that is true on the margin–there is some low-hanging fruit.

In other pollution news. It is clear that pollution papers are becoming a growth industry and thus there are bound to be green jelly bean problems. I haven’t read either closely but I did note that Roy et al. find that pollution increases mutual fund errors and Du finds that pollution increases racist tweets. Well, maybe. The new pollution literature is credible but remember to trust literatures not papers.

Air Pollution and Student Performance in the U.S.

We combine satellite-based pollution data and test scores from over 10,000 U.S. school districts to estimate the relationship between air pollution and test scores. To deal with potential endogeneity we instrument for air quality using (i) year-to-year coal production variation and (ii) a shift-share instrument that interacts fuel shares used for nearby power production with national growth rates. We find that each one-unit increase in particulate pollution reduces test scores by 0.02 standard deviations. Our findings indicate that declines in particulate pollution exposure raised test scores and reduced the black-white test score gap by 0.06 and 0.01 standard deviations, respectively.

That is from Michael Gilraine and Angela Zheng. Maybe you, like me, do not find any one of these studies to be a real clincher. But please do reread Alex on the sum total of the evidence…and here.

Air pollution and the history of economic growth

I have not had the chance to read this through, but here goes:

Documenting environmental pollution damage affects the magnitude of aggregate output, net of pollution damage, and the contribution to national product across economic sectors. For example, air pollution damage from the production side of the economy amounted to over 5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2002…

I have presented estimates of these effects in the US economy between 1957 and 2016. This period featured the passage of the Clean Air Act (CAA) in 1970 and its subsequent implementation through the 1970s, as well as several business cycles. This research suggests that pollution damage began to decrease just after the CAA was enacted, and the orientation between GDP growth and that of the adjusted measure, or environmentally adjusted value added (EVA), switched.

That is from Nicholas J. Muller, all a bit awkwardly worded. Jeremy Horpedahl is more to the point:

If we use the standard measure of GDP, growth indeed slowed down after 1970. If instead we augment GDP for environmental damages, the period after 1970 was actually faster! The adjustment both slows down growth from 1957-1970, and speeds up growth after 1970.

Worth a ponder.

Why the New Pollution Literature is Credible

My recent post, Air Pollution Reduces Health and Wealth drew some pushback in the comments, some justified, some not, on whether the results of these studies are not subject to p-hacking, forking gardens and the replication crisis. Sure, of course, some of them are. Andrew Gelman, for example, has some justified doubt about the air filters and classroom study. Nevertheless, I don’t think that skepticism about the general thrust of the results is justified. Why not?

My recent post, Air Pollution Reduces Health and Wealth drew some pushback in the comments, some justified, some not, on whether the results of these studies are not subject to p-hacking, forking gardens and the replication crisis. Sure, of course, some of them are. Andrew Gelman, for example, has some justified doubt about the air filters and classroom study. Nevertheless, I don’t think that skepticism about the general thrust of the results is justified. Why not?

First, go back to my post Why Most Published Research Findings are False and note the list of credibility checks. For example, my rule is trust literatures not papers and the new pollution literature is showing consistent and significant negative effects of pollution on health and wealth. Some might respond that the entire literature is biased for reasons of political correctness or some such and sure, maybe. But then what evidence would be convincing? Is skepticism then justified or merely mood affiliation? And when it comes to action should we regard someone’s prior convictions (how were those formed?) as more accurate then a large, well-published scientific literature?

It’s not just that the literature is large, however, it’s that the literature is consistent in a way that many studies in say social psychology were not. In social psychology, for example, there were many tests of entirely different hypotheses–power posing, priming, stereotype threat–and most of these failed to replicate. But in the pollution literature we have many tests of the same hypotheses. We have, for example, studies showing that pollution reduces the quality of chess moves in high-stakes matches, that it reduces worker productivity in Chinese call-centers, and that it reduces test scores in American and in British schools. Note that these studies are from different researchers studying different times and places using different methods but they are all testing the same hypothesis, namely that pollution reduces cognitive ability. Thus, each of these studies is a kind of replication–like showing price controls led to shortages in many different times and places.

Another feature in favor of the air pollution literature is that the hypothesis that pollution can have negative effects on health and cognition wasn’t invented yesterday along with the test (we came up with a new theory and tested it and guess what, it works!). The Romans, for example, noted the negative effect of air pollution on health. There’s a reason why people with lung disease move to the countryside and always have.

I also noted in Why Most Published Research Findings are False that multiple sources and types of evidence are desirable. The pollution literature satisfies this desideratum. Aside from multiple empirical studies, the pollution hypothesis is also consistent with plausible mechanisms and it is consistent with the empirical and experimental literature on pollution and plants and pollution and animals. See also OpenPhilanthropy’s careful summary.

Moreover, there is a clear dose-response effect–so much so that when it comes to “extreme” pollution few people doubt the hypothesis. Does anyone doubt, for example, that an infant born in Delhi, India–one of the most polluted cities in the world–is more likely to die young than if the same infant grew up (all else equal) in Wellington, New Zealand–one of the least polluted cities in the world? People accept that “extreme” pollution creates debilitating effects but they take extreme to mean ‘more than what I am used to’. That’s not scientific. In the future, people will think that the levels of pollution we experience today are extreme, just as we wonder how people could put up with London Fog.

What is new about the new pollution literature is more credible methods and bigger data and what the literature shows is that the effects of pollution are larger than we thought at lower levels than we thought. But we should expect to find smaller effects with better methods and bigger data. (Note that this isn’t guaranteed, there could be positive effects of pollution at lower levels, but it isn’t surprising that what we are seeing so far is negative effects at levels previously considered acceptable.)

Thus, while I have no doubt that some of the papers in the new pollution literature are in error, I also think that the large number of high quality papers from different times and places which are broadly consistent with one another and also consistent with what we know about human physiology and particulate matter and also consistent with the literature on the effects of pollution on animals and plants and also consistent with a dose-response relationship suggest that we take this literature and its conclusion that air pollution has significant negative effects on health and wealth very seriously.

Air Pollution Reduces Health and Wealth

Great piece by David Wallace-Wells on air pollution.

Here is just a partial list of the things, short of death rates, we know are affected by air pollution. GDP, with a 10 per cent increase in pollution reducing output by almost a full percentage point, according to an OECD report last year. Cognitive performance, with a study showing that cutting Chinese pollution to the standards required in the US would improve the average student’s ranking in verbal tests by 26 per cent and in maths by 13 per cent. In Los Angeles, after $700 air purifiers were installed in schools, student performance improved almost as much as it would if class sizes were reduced by a third. Heart disease is more common in polluted air, as are many types of cancer, and acute and chronic respiratory diseases like asthma, and strokes. The incidence of Alzheimer’s can triple: in Choked, Beth Gardiner cites a study which found early markers of Alzheimer’s in 40 per cent of autopsies conducted on those in high-pollution areas and in none of those outside them. Rates of other sorts of dementia increase too, as does Parkinson’s. Air pollution has also been linked to mental illness of all kinds – with a recent paper in the British Journal of Psychiatry showing that even small increases in local pollution raise the need for treatment by a third and for hospitalisation by a fifth – and to worse memory, attention and vocabulary, as well as ADHD and autism spectrum disorders. Pollution has been shown to damage the development of neurons in the brain, and proximity to a coal plant can deform a baby’s DNA in the womb. It even accelerates the degeneration of the eyesight.

A high pollution level in the year a baby is born has been shown to result in reduced earnings and labour force participation at the age of thirty. The relationship of pollution to premature births and low birth weight is so strong that the introduction of the automatic toll system E-ZPass in American cities reduced both problems in areas close to toll plazas (by 10.8 per cent and 11.8 per cent respectively), by cutting down on the exhaust expelled when cars have to queue. Extremely premature births, another study found, were 80 per cent more likely when mothers lived in areas of heavy traffic. Women breathing exhaust fumes during pregnancy gave birth to children with higher rates of paediatric leukaemia, kidney cancer, eye tumours and malignancies in the ovaries and testes. Infant death rates increased in line with pollution levels, as did heart malformations. And those breathing dirtier air in childhood exhibited significantly higher rates of self-harm in adulthood, with an increase of just five micrograms of small particulates a day associated, in 1.4 million people in Denmark, with a 42 per cent rise in violence towards oneself. Depression in teenagers quadruples; suicide becomes more common too.

Stock market returns are lower on days with higher air pollution, a study found this year. Surgical outcomes are worse. Crime goes up with increased particulate concentrations, especially violent crime: a 10 per cent reduction in pollution, researchers at Colorado State University found, could reduce the cost of crime in the US by $1.4 billion a year. When there’s more smog in the air, chess players make more mistakes, and bigger ones. Politicians speak more simplistically, and baseball umpires make more bad calls.

As MR readers will know Tyler and I have been saying air pollution is an underrated problem for some time. Here’s my video on the topic:

Ordinary air pollution is still an underrated problem

That is the theme of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

More than 10 million people die each year from air pollution, according to a new study — far more than the estimated 2.6 million people who have died from Covid-19 since it was detected more than a year ago. And while Covid is headline news, ordinary air pollution remains a side issue for policy wonks and technocrats.

[To be clear, I am not seeking to minimize Covid as a major issue.] And:

Why aren’t these deaths a bigger issue in U.S. political and policy discourse? One reason may be that 62% of those deaths are in China and India. The number of premature deaths due to particulate matter in North America was 483,000, just slightly lower than the number of measured deaths from Covid to date. An estimated 876 of those deaths were of children under the age of 4.

Another reason for the weak political salience of the issue may be its invisibility. Air pollution causes many deaths. But it is rare to see or read about a person dying directly from air pollution. Lung cancer and cardiac disease are frequently cited as causes of death, even though they may stem from air pollution.

Another problem is that the question of how to better fight air pollution does not fit neatly into current ideological battles. You might think Democrats would emphasize this issue, but much of the economic burden of tougher action would fall on the Northeast, a largely Democratic-leaning area.

And exactly how many people die each year from global warming? Why not have a greater focus on ordinary air pollution?

Pollution is an Attack on Human Capital

Here’s the latest video from MRU where I cover some interesting papers on the effect of pollution on health, cognition and productivity. The video is pre-Covid but one could also note that pollution makes Covid more dangerous. For principles of economics classes the video is a good introduction to externalities and also to causal inference, most notably the difference in difference method.

Might I also remind any instructor that Modern Principles of Economics has more high-quality resources to teach online than any other textbook.

Pollution in India and the World

I spoke on the negative effects of air pollution on health and GDP at Brookings India in Delhi. The talk was covered by Indian media. The Print had a good overview:

I spoke on the negative effects of air pollution on health and GDP at Brookings India in Delhi. The talk was covered by Indian media. The Print had a good overview:

The long-held belief that pollution is the cost a country has to pay for development is no longer true as bad air quality has a measurable detrimental impact on human productivity that could in turn reduce GDP, Canadian-American economist Alex Tabarrok said.

…“There is this old story that pollution is bad, but it increases GDP… When the United States and Japan were developing, they were polluted. So India and China also have to go through that stage of pollution — so that they get rich, and then they can afford to reduce pollution,” Tabarrok said.

“I want to say that that story is wrong. What I want to argue is that a lot of the new research indicates that we may be in a situation where we could be both healthier and wealthier at the same time by reducing pollution,” he said.

…At the seminar, Tabarrok pointed out that expecting people to make sacrifices for the sake of future generations is not a politically fruitful way to deal with pollution.

Citing the issue of crop burning in India, he said farmers are not going to be inclined to change their behaviour if they are told to stop stubble burning for the sake of Delhi residents.

“However, if these farmers are made aware of how the crop burning harms them and their families and affects their soil quality, they are more likely to participate in mitigation measures,” he said.

I was pretty tough on government policy as Business Today India reported:

More than half of India’s population lives in highly polluted areas. Research by Greenstone et al (2015) proves that 660 million people live in areas that exceed the Indian Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) for fine particulate pollution. In this context, having measures such as banning e-cigarettes and having odd-even days for vehicles to solve the problem of air pollution seems ridiculous, says Alex Tabarrok, Professor of Economics at the George Mason University and Research Fellow with the Mercatus Centre. “These are not appropriate solutions to the scale and the dimensions of the problem,” he says.

Patents, Pollution, and Pot

In recent years, new research has significantly increased my belief that air pollution has substantial negative effects on productivity, IQ and health (see previous posts). Research in the field is exploding which means that there must also be more false positives. Consider two recent papers. The first, The Real Effect of Smoking Bans: Evidence from Corporate Innovation by Gao et al. finds that smoking prohibition increased patenting!

We identify a positive causal effect of healthy working environments on corporate innovation, using the staggered passage of U.S. state-level laws that ban smoking in workplaces. We find a significant increase in patents and patent citations for firms headquartered in states that have adopted such laws relative to firms headquartered in states without such laws. The increase is more pronounced for firms in states with stronger enforcement of such laws and in states with weaker preexisting tobacco controls. We present suggestive evidence that smoke-free laws affect innovation by improving inventor health and productivity and by attracting more productive inventors.

But the second, Do Firms Get High? The Impact of Marijuana Legalization on Firm Performance, Corporate Innovation, and Entrepreneurial Activity by Wang et al. finds that marijuana legalization increased patenting!

We find that state-level marijuana legalization has a positive financial impact on firms, likely by affecting firms’ human capital. Firms headquartered in marijuana-legalizing states receive higher market valuations, earn higher abnormal stock returns, improve employee productivity, and increase innovation. Exploiting firm level inventor data, we directly test the human capital channel and find that post legalization, firms retain inventors that become more productive and recruit more innovative talents from out of state. We also find that marijuana-legalizing states experience an increase in the number of new startups and venture capital investments.

Would anyone have been surprised if these two papers had shown exactly the opposite results? Indeed, there is some evidence that nicotine is solid cognitive enhancer and Tyler recently argued, on the basis of good evidence, that pot makes people dumb. Is it a coincidence that anti-cigarette and pro-pot papers appear as the country moves in this direction? Social desirability bias also applies to research. So no knock on either paper but I am unconvinced. As I like to say, trust literatures not papers.

Hat tip: The excellent Kevin Lewis.