Category: Education

I talk talent networks and mentoring and Christianity with Luke Burgis

From Grand Rapids, Michigan, earlier in the year, here is the link.

Here is Luke’s Cluny Institute, which sponsored the event. And here is Luke’s book on Rene Girard.

What should I ask Arthur C. Brooks?

Yes I will be doing a Conversation with him. Here is Wikipedia:

Since 2019, Brooks has served as the Parker Gilbert Montgomery Professor of the Practice of Nonprofit and Public Leadership at the Harvard Kennedy School and at the Harvard Business School as a Professor of Management Practice and Faculty Fellow.[2] Previously, Brooks served as the 11th President of the American Enterprise Institute. He is the author of thirteen books, including Build the Life You Want: The Art and Science of Getting Happier with co-author Oprah Winfrey (2023), From Strength to Strength: Finding Success, Happiness and Deep Purpose in the Second Half of Life (2022), Love Your Enemies (2019), The Conservative Heart (2015), and The Road to Freedom (2012). Since 2020, he has written the Atlantic’s How to Build a Life column on happiness.

Do not forget Arthur started as a professional French hornist, and also was well known in the cultural economics field during his Syracuse University days. And more. So what should I ask him?

Emergent Ventures winners, 49th cohort

David Yang, 14, Vancouver, robotics.

Alex Araki, London, to improve clinical trials.

Ivan Skripnik, Moldova/LA, physics and the nature of space.

Mihai Codreanu, Stanford economics Ph.D, industrial parks and the origins of innovation.

Salvador Duarte, Lisbon/Nebraska, 17, podcast in economics and philosophy.

Aras Zirgulis, Vilnius, short economics videos.

Ava McGurk, 17, Belfast, therapy and other services company and general career support.

Anusha Agarwal, Thomas Jefferson High School, NoVa, space/Orbitum.

Cohen Pert, 16, Sewanee, Georgia, running several businesses.

Jin Wang, University of Arizona, Economics Ph.D, AI and the history of Chinese economic growth.

Janelle Yapp, high school senior, KL Malaysia, general career support.

Justin Kuiper, Bay Area, Progress Studies ideas for video.

Mariia ]Masha] Baidachna, Glasgow/Ukraine, quantum computing.

Beatriz Gietner, Dublin, Substack on econometrics.

Roman Lopatynskyi, Kyiv, romantic piano music.

Eric Hanushek on the import of schooling quality declines

My recent research at Stanford University translates the achievement declines into implications for future economic impacts. Past evidence shows clearly that people who know more earn more. When accounting for the impact of higher achievement historically on salaries, the lifetime earnings of today’s average student will be an estimated 8 percent lower than that of students in 2013. Because long-term economic growth depends on the quality of a nation’s labor force, the achievement declines translate into an average of 6 percent lower gross domestic product for the remainder of the century. The dollar value of this lower growth is over 15 times the total economic costs of the 2008 recession.

Here is the full Op-Ed, noting that Eric compares this decline to the effects of an eight percent income tax surcharge. I have not read through this work, though I suspect these estimates will prove controversial when it comes to causality. In any case, file this under “big if true,” if only in expected value terms.

Confidently Wrong

If you’re going to challenge a scientific consensus, you better know the material. Most of us, most of the time, don’t—so deferring to expert consensus is usually the rational strategy. Pushing against the consensus is fine; it’s often how progress happens. But doing it responsibly requires expertise. Yet in my experience the loudest anti-consensus voices—on vaccines, climate, macroeconomics, whatever—tend to be the least informed.

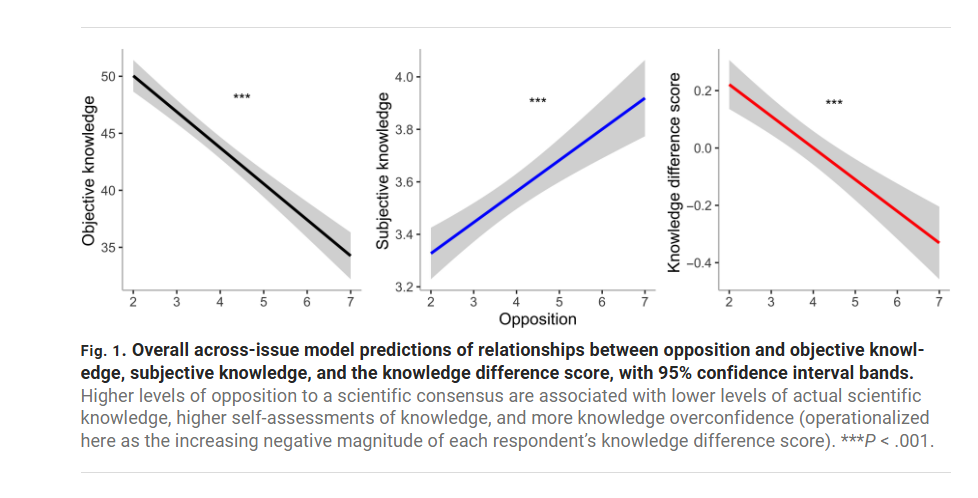

This isn’t just my anecdotal impression. A paper by Light, Fernbach, Geana, and Sloman shows that opposition to the consensus is positively correlated with knowledge overconfidence. Now you may wonder. Isn’t this circular? If someone claims the consensus view is wrong we can’t just say that proves they don’t know what they are talking about. Indeed. Thus Light, Fernbach, Geana and Sloman do something clever. They ask respondents a series of questions on uncontroversial scientific topics. Questions such as:

1. True or false? The center of the earth is very hot: True

2. True or false? The continents have been moving their location for millions of years and will continue to move. True

3. True or false? The oxygen we breathe comes from plants: True

4. True or false? Antibiotics kills viruses as well as bacteria: False

5. True or false? All insects have eight legs: False

6. True or false? All radioactivity is man made: False

7. True or false? Men and women normally have the same number of chromosomes: True

8. True or false? Lasers work by focusing sound waves: False

9. True or false? Almost all food energy for living organisms comes originally from sunlight: True

10. True or false? Electrons are smaller than atoms: True

The authors then correlate respondents’ scores on the objective (uncontroversial) knowledge with their opposition to the scientific consensus on topics like vaccination, nuclear power, and homeopathy. The result is striking: people who are most opposed to the consensus (7, the far right of the horizontal axis in the figure below) score lower on objective knowledge but express higher subjective confidence. In other words, anti-consensus respondents are the most confidently wrong—the gap between what they know and what they think they know is widest.

In a nice test the authors show that the confidently wrong are not just braggadocios they actually believe they know because they are more willing to bet on the objective knowledge questions and, of course, they lose their shirts. A bet is a tax on bullshit.

The implications matter. The “knowledge deficit” approach (just give people more fact) breaks down when the least-informed are also the most certain they’re experts. The authors suggest leaning on social norms and respected community figures instead. My own experience points to the role of context: in a classroom, the direction of information flow is clearer, and confidently wrong pushback is rarer than on Twitter or the blog. I welcome questions in class—they’re usually great—but they work best when there’s at least a shared premise that the point is to learn.

Hat tip: Cremieux

The MR Podcast: Tariffs!

On The Marginal Revolution Podcast this week, Tyler and I discuss tariffs! Here’s one bit:

COWEN: I have a new best argument against tariffs. It’s very soft. I think it’s hard to prove, but it might actually be the very best argument against tariffs.

TABARROK: All right, let’s hear it.

COWEN: If you think about COVID policy, the wealthy nations did a bunch of things. Some of them were quite bad, and the poorer nations all copied that. They didn’t have to copy it, but there was some kind of contagion effect, or that seemed like the high-status thing to do. I believe with tariffs, something similar goes on. There’s a huge literature about retaliation. Of course, retaliation is a cost, that’s bad, but simply the copying effect that it was high status for the wealthy nations to have tariffs. They can afford it better, but then places like India had their own version of the same thing. That was just terrible for India at a much higher human cost than, say, it was for the United States. Again, it’s hard to trace or prove, but that I think could actually be the best argument against tariffs, simply that poorer countries will copy what the high-status nations are doing.

This is like Rob Henderson’s idea of luxury beliefs, beliefs which the elite can proffer at low cost but which have negative consequences when adopted by working and lower classes. Tariffs aren’t great for the US but the US is so large and rich we can handle it but if the idea is adopted by poorer nations it will be much worse for them. I wish I had been clever enough to say this during the podcast but I never know what Tyler will say in advance.

Here’s another bit:

TABARROK: Here’s the question which the Trumpers or other people never really answer is, what are we going to have less of? Yes, we’ll have more investment. Let’s say we get another auto plant. The unemployment rate is 4%, so it’s not like we have a lot of free resources around. Most of the time, we’re in full equilibrium. If we have more auto plant workers and more cars being produced in the United States, we’re going to have less of something. I think it is incumbent on people who want tariffs in order to get more employment in manufacturing or something like that to say, “Well, what are we going to have less of?”

COWEN: The more sophisticated ones of them, I think, would say, well, the US is super high on the consumption scale, even relative to our very high per capita incomes. If we end up spending some of that consumption on boosting real wages, it’s actually a good investment, if only in political sanity, stability, fewer opioid deaths. It’s a very indirect chain of reasoning. I would say I’m skeptical. Again, it’s not a crazy argument. It’s a weird kind of industrial policy where you channel resources away from consumption into investment and higher wages. A lot of those plants are automated. They’re going to be automated much yet. It’s further stuff, maybe to other robotics companies or the AI companies. Again, I think that’s what they would say.

TABARROK: I don’t think they would say that.

COWEN: No, the more sophisticated ones.

TABARROK: Are there? I haven’t seen too many of those….

Here’s the episode. Subscribe now to take a small step toward a much better world: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube.

Do (human) readers prefer AI writers?

It seems so, do read through the whole abstract:

The use of copyrighted books for training AI models has led to numerous lawsuits from authors concerned about AI’s ability to generate derivative content. Yet it’s unclear whether these models can generate high quality literary text while emulating authors’ styles/voices. To answer this we conducted a preregistered study comparing MFA-trained expert writers with three frontier AI models: ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini in writing up to 450 word excerpts emulating 50 awardwinning authors’ (including Nobel laureates, Booker Prize winners, and young emerging National Book Award finalists) diverse styles. In blind pairwise evaluations by 159 representative expert (MFA-trained writers from top U.S. writing programs) and lay readers (recruited via Prolific), AI-generated text from in-context prompting was strongly disfavored by experts for both stylistic fidelity (odds ratio [OR]=0.16, p < 10^-8) and writing quality (OR=0.13, p< 10^-7) but showed mixed results with lay readers. However, fine-tuning ChatGPT on individual author’s complete works completely reversed these findings: experts now favored AI-generated text for stylistic fidelity (OR=8.16, p < 10^-13) and writing quality (OR=1.87, p=0.010), with lay readers showing similar shifts. These effects are robust under cluster-robust inference and generalize across authors and styles in author-level heterogeneity analyses. The fine-tuned outputs were rarely flagged as AI-generated (3% rate versus 97% for incontext prompting) by state-of-the-art AI detectors. Mediation analysis reveals this reversal occurs because fine-tuning eliminates detectable AI stylistic quirks (e.g., cliché density) that penalize incontext outputs, altering the relationship between AI detectability and reader preference. While we do not account for additional costs of human effort required to transform raw AI output into cohesive, publishable novel length prose, the median fine-tuning and inference cost of $81 per author represents a dramatic 99.7% reduction compared to typical professional writer compensation. Author-specific fine-tuning thus enables non-verbatim AI writing that readers prefer to expert human writing, thereby providing empirical evidence directly relevant to copyright’s fourth fair-use factor, the “effect upon the potential market or value” of the source works.

That is from a new paper by Tuhin Chakrabarty, Jane C. Ginsburg, and Paramveer Dhillon. For the pointer I thank the excellent Kevin Lewis. I recall an earlier piece showing that LLMs also prefer LLM outputs?

“May I meet you?”

Bill Ackman suggests that opener as a way for men to meet women, and notes it worked for him when he was younger and unmarried. Like this: “I would ask: “May I meet you?” before engaging further in a conversation. I almost never got a No. It inevitably enabled the opportunity for a further conversation. I met a lot of really interesting people this way. I think the combination of proper grammar and politeness was the key to its effectiveness. You might give it a try.”

In response, a bunch of people have shrieked that he is a billionaire (he was not then, though perhaps he had Aristotelian billionaire potentiality?), that he is six foot three (he probably was tall back then too), and that he is good looking. Or perhaps effective meeting and dating strategies have changed?

I readily admit I am well below average in this and all related areas concerning either meeting strangers or chatting up women, whether it concerns knowledge or praxis. But I have an opinion nonetheless.

I observe that so many young men these days just do not make much effort at all. They do not approach women with any sort of opening line, whether in person or through apps. If this gets them off the zero point, it is almost certainly a good thing. Maybe it is bad tactics for some people, if only because you are too nerdy and cannot deliver the words with the right charming tone. So be it. The young men with that problem can then adjust and try it some other way. It is still a plus to get them thinking about opening lines at all, and to think about meeting women at all. So I am fully on board with Bill’s suggestion. He never said that is all you should be doing, or to make that your main thing. It is unlikely that his suggestion is the best thing you could be doing, think of it simply as pressing the “activation button” on seeking a partner.

It is a bit like my advice on writing. Your big enemy is not “I did not get enough written today.” Rather it is “I did not write today at all.” That point applies to so many different aspects of life. Discrete choice econometrics!

Addendum: Bill adds that it works better when you are moving. Let’s avoid this equilibrium. And here are some other comments, I am not sure of the proper attribution.

Emergent Ventures winners 48th cohort

Minh Nguyen, Dallas, 16, to address problems of space debris.

Serena Chen and Valerie Wu, Taipei and Los Angeles, better blood transportation.

Griffin Li, Boston, 19, general career support, issues in market pricing on apps.

Jamie Croucher, London, for a new scientific society, Society for Technological Advancement.

Sri Anumakonda, Carnegie Mellon, robotic hands.

Ben James, London, lowering the price of electricity.

Lucio Aurelio Moreira Menezes, Fortaleza and Stanford, computational biology.

Lauren Gilbert, London, a progress-oriented magazine for the developing world?

Annika Baberwal, Dubai, 8th grade, helping race cars run faster.

Bernardo Melotti, Bologna/Stanford, equipment to speed biological advances.

Elyas Sepahi, London, mathematics and machine learning.

Harishvin Sashikumar, Vancouver, 17, brain interfaces.

The Effect of Video Watching on Children’s Skills

This paper documents video consumption among school-aged children in the U.S. and explores its impact on human capital development. Video watching is common across all segments of society, yet surprisingly little is known about its developmental consequences. With a bunching identification strategy, we find that an additional hour of daily video consumption has a negative impact on children’s noncognitive skills, with harmful effects on both internalizing behaviors (e.g., depression) and externalizing behaviors (e.g., social difficulties). We find a positive effect on math skills, though the effect on an aggregate measure of cognitive skills is smaller and not statistically significant. These findings are robust and largely stable across most demographics and different ways of measuring skills and video watching. We find evidence that for Hispanic children, video watching has positive effects on both cognitive and noncognitive skills—potentially reflecting its role in supporting cultural assimilation. Interestingly, the marginal effects of video watching remain relatively stable regardless of how much time children spend on the activity, with similar incremental impacts observed among those who watch very little and those who watch for many hours.

That is from a new NBER working paper by

My first trip to Tokyo

To continue with the biographical segments:

My first trip to Tokyo was in 1992. I was living in New Zealand at the time, and my friend Dan Klein contacted me and said “Hey, I have a work trip to Tokyo, do you want to meet me there?” And so I was off, even though the flight was more of a drag than I had been expecting. It is a long way up the Pacific.

Narita airport I found baffling, and it was basically a two hour, multi-transfer trip to central Tokyo. Fortunately, a Japanese woman was able to help us make the connections. I am glad these days that the main flights come into Haneda.

(One Japan trip, right before pandemic, I decided to spend a whole day in Narita proper. Definitely recommended for its weirdness. Raw chicken was served in the restaurants, and it felt like a ghost town except for some of the derelicts in the streets. This experience showed me another side of Japan.)

We stayed in a business hotel in Ikebukuro, a densely populated but not especially glamorous part of Tokyo. It turned out that was a good way to master the subway system and also to get a good sense of how Tokyo was organized. I had to one-shot memorize the rather complicated footpath from the main subway station to the hotel, which had been chosen by my friend’s sponsors. As we first emerged from the subway station, we had, getting there the first time, to ask two Japanese high schoolers to help us find the way. They spoke only a few words of English, but we showed them the address in Japanese and they even carried our bags for us, grunting “Hai!” along the way, giving us a very Japanese experience.

In those days very little English was spoken in Tokyo, especially outside a few major areas such as Ginza. You were basically on your own.

I recall visiting the Sony Center, which at the time was considered the place to go to see new developments in “tech.” I marveled at the 3-D TV, and realized we had nothing like it. I felt like I was glimpsing the future, but little did I know the technology was not going anywhere. Nor for that matter was the company. Here is Noah, wanting the Japanese future back.

Most of all, Tokyo was an extreme marvel to me. I felt it was the single best and most interesting place I had visited. Everywhere I looked — even Ikebukuro — there was something interesting to take note of. The plastic displays of food in the windows (now on the way out, sadly) fascinated me. The diversity, order, and package wrapping sensibilities of the department stores were amazing. The underground cities in the subways had to be seen to be believed (just try emerging from Shinjuku station and finding the right exit). The level of dress and stylishness and sophistication was extreme, noting I would not say the same about Tokyo today. This was not long after the bubble had burst, but the city still had the feel of prosperity. Everything seemed young and dynamic.

I also found Tokyo affordable. The reports of the $2,000 melon were true, but the actual things you would buy were somewhat cheaper than in say New York City. It was easy to get an excellent meal for ten dollars, and without much effort. My hotel room was $50 a night. The subway was cheap, and basically you could walk around and look at things for free. The National Museum was amazing, one of the best in the world and its art treasures cannot, in other forms, readily be seen elsewhere.

Much as I like Japanese food, I learned during this trip that I cannot eat it many meals in a row. This was the journey where I realized Indian food (!) is my true comfort food. Tokyo of course has (and had) excellent Indian food, just as it has excellent food of virtually every sort. I learned a new kind of Chinese food as well.

The summer heat did not bother me. I also learned that Tokyo is one of the few cities that is better and more attractive at night.

I recall wanting to buy a plastic Godzilla toy. I walked around the proper part of town, and kept on asking for Godzilla. I could not figure out why everyone was staring at me like I was an idiot, learning only later that the Japanese say “Gojira.” So in a pique of frustration, I did my best fire-breathing, stomping around, “sound like a gorilla cry run backwards through the tape” imitation of Godzilla. Immediately a Japanese man excitedly grabbed me by the hand, walked me through some complicated market streets, and showed me where I could buy a Godzilla, shouting “Gojira, Gojira, Gojira!” the whole time.

I came away happy.

My side trip, by the way, was to the shrines and temples of Kamakura, no more than an hour away but representing another world entirely. Recommended to any of you who are in Tokyo with a day to spare.

Now since that time, I’ve never had another Tokyo trip quite like that one. These days, and for quite a while, the city feels pretty normal to me, rather than like visiting the moon. Fluent English is hard to come by, but most people can speak some English and respond to queries. You can translate and get around using GPS, AI, and so on. The city is much more globalized, and other places have borrowed from its virtues as well.

Looking back, I am very glad I visited Tokyo in 1992. The lesson is that you can in fact do time travel. You do it by going to some key places right now.

UCSD Faculty Sound Alarm on Declining Student Skills

The UC San Diego Senate Report on Admissions documents a sharp decline in students’ math and reading skills—a warning that has been sounded before, but this time it’s coming from within the building.

At our campus, the picture is truly troubling. Between 2020 and 2025, the number of freshmen whose math placement exam results indicate they do not meet middle school standards grew nearly thirtyfold, despite almost all of these students having taken beyond the minimum UCOP required math curriculum, and many with high grades. In the 2025 incoming class, this group constitutes roughly one-eighth of our entire entering cohort. A similarly large share of students must take additional writing courses to reach the level expected of high school graduates, though this is a figure that has not varied much over the same time span.

Moreover, weaknesses in math and language tend to be more related in recent years. In 2024, two out of five students with severe deficiencies in math also required remedial writing instruction. Conversely, one in four students with inadequate writing skills also needed additional math preparation.

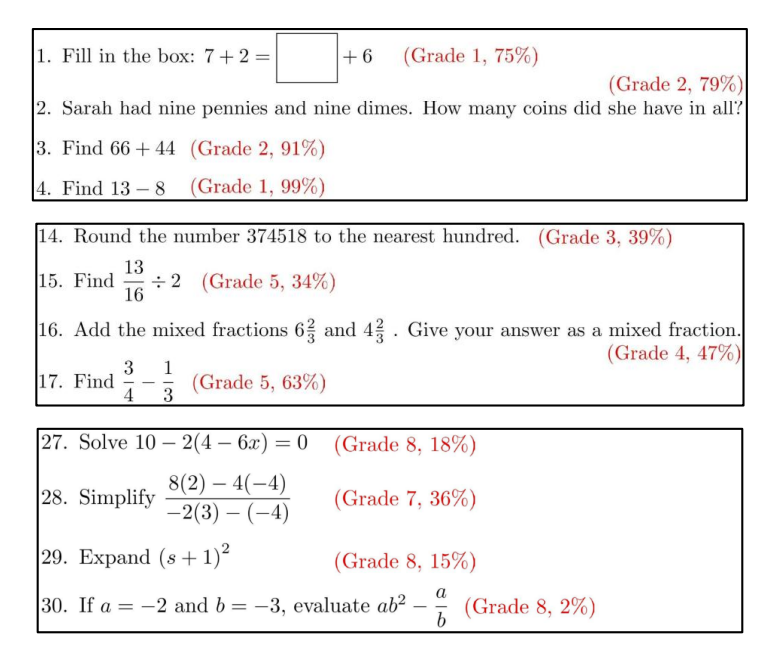

The math department created a remedial course, only to be so stunned by how little the students knew that the class had to be redesigned to cover material normally taught in grades 1 through 8.

Alarmingly, the instructors running the 2023-2024 Math 2 courses observed a marked change in the skill gaps compared to prior years. While Math 2 was designed in 2016 to remediate missing high school math knowledge, now most students had knowledge gaps that went back much further, to middle and even elementary school. To address the large number of underprepared students, the Mathematics Department redesigned Math 2 for Fall 2024 to focus entirely on elementary and middle school Common Core math subjects (grades 1-8), and introduced a new course, Math 3B, so as to cover missing high-school common core math subjects (Algebra I, Geometry, Algebra II or Math I, II, III; grades 9-11).

In Fall 2024, the numbers of students placing into Math 2 and 3B surged further, with over 900 students in the combined Math 2 and 3B population, representing an alarming 12.5% of the incoming first-year class (compared to under 1% of the first-year students testing into these courses prior to 2021)

(The figure gives some examples of remedial class material and the percentage of remedial students getting the answers correct.)

The report attributes the decline to several factors: the pandemic, the elimination of standardized testing—which has forced UCSD to rely on increasingly inflated and therefore useless high school grades—and political pressure from state lawmakers to admit more “low-income students and students from underrepresented minority groups.”

…This situation goes to the heart of the present conundrum: in order to holistically admit a diverse and representative class, we need to admit students who may be at a higher risk of not succeeding (e.g. with lower retention rates, higher DFW rates, and longer time-to-degree).

The report exposes a hard truth: expanding access without preserving standards risks the very idea of a higher education. Can the cultivation of excellence survive an egalitarian world?

Educational for-profit charter schools do worse in Sweden

I estimate the long-run earnings impacts of for-profit and non-profit charter high schools in Sweden. Since the 1990s, privately managed schools have expanded dramatically—driven entirely by for-profit providers—and now enroll nearly half of urban high school students. Unlike in many other settings, there are no schools operating outside of the public system: all schools rely on equal public funding, cannot charge top-up fees, and are subject to the same regulation. Using a combination of value-added and regression discontinuity methods, I find that charter school attendance reduces long-run earnings by 2% on average—comparable to the returns to half a year of schooling in similar settings. For-profits generate these losses by hiring less-educated, lower-paid teachers, consistent with concerns around cost-cutting. By contrast, non-profits reduce earnings by specializing in arts programs: conditional on such specialization, they perform as or even better than public schools. In a discrete choice framework using rank-ordered school applications, I show that students’ preferences are weakly related to schools’ earnings impacts. Most of the for-profit market share is explained by student demand for attractive locations and study programs, presenting a trade-off between satisfying short-run demand and boosting long-run economic outcomes.

That is the job market paper from Petter Berg, from Stockholm School of Economics.

Emergent Ventures India, 12th cohort

Harish Ashok, 16, received his grant to build a multi-purpose rover.

Dev Patel, economist, received his grant to expand his method combining machine learning and geophysics to detect and forecast floods across Indian villages.

Saurabh Chandra, Pranay Kotasthane, and Khyati Pathak received their grant for Puliyabaazi Hindi Podcast, to expand and develop articles and video formats in simple, conversational Hindi.

Vishrant Dave, Ayush Ranjan and Prateesh Awasthi received their grant for Armatrix, hyper-redundant robotic arms for inspection and maintenance in hard-to-reach and hazardous industrial environments.

Akhil Reddy K received his grant for Livestockify, to develop solar-powered IoT sensors for real-time poultry disease and health monitoring.

Mohil Ahuja, 19, received his grant to develop a low-cost algae-based air purification system addressing indoor pollution.

Reivanth Kanagaraj received his grant for ColourCryption, to create low-cost anti-counterfeiting solutions using fluorescent inks.

Kaviraj Prithvi, 23, received his grant for uDot, to build a tactile display enabling blind students to study STEM.

Tawheed Rahman, highschooler, received his grant to build a low-cost prosthetic robotic arm.

Keya Shah, 22, received her grant to develop a prosthetics solution in Bangalore.

Sanjay Ganguli received his grant to acquire equipment for documenting wildlife stories from India.

Avhijit Nair, 26, received his grant for HydroPlas Tech, to produce graphene from waste plastic.

Rain Regious received his grant for TRIPd, to develop a wearable revolutionizing personal temperature control through thermoreceptors.

Pragyaan Gaur, 18, received his grant to build technology reducing industrial sulfur dioxide emissions.

Wajih ur Rehman received his grant to develop an aerosol-technology-based solution to curb air pollution in Pakistan.

Rakshith Aloori, 25, received his grant to build desalination machines solving the water crisis.

Prashansa Tripathi, doctoral student at IIT Jodhpur, received travel and conference support to attend the cognitive neuroscience skills training program at Cambridge University.

Those unfamiliar with Emergent Ventures can learn more here and here. The EV India announcement is here. More about the winners of EV India second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth, and eleventh cohorts. To apply for EV India, use the EV application, click the “Apply Now” button and select India from the “My Project Will Affect” drop-down menu.

And here is Nabeel’s AI engine for other EV winners. Here are the other EV cohorts.

If you are interested in supporting the India tranche of Emergent Ventures, please write to me or to Shruti at [email protected].

TC again: I thank Shruti for preparing this blog post, and for all the work behind it!

Very good sentences

TL;DR: AI now solves university assignments perfectly in minutes. Students often use LLMs as a crutch rather than as a tutor, getting answers without understanding. To address these problems, I propose a barbell strategy: pure fundamentals (no AI) on one end, full-on AI projects on the other, with no mushy middle. Universities should focus on fundamentals.

That is from Simas at Inexact Science.